Introduction:

Hello, I'm David McCullough. Welcome to The American Experience.

David McCullough, Series Host: Hello and welcome to The American Experience. I'm David McCullough.

In Boston the stock market closed. In Pennsylvania a statewide order shut down every place of amusement, every saloon. In Kentucky the Board of Health prohibited public gatherings of any kind, even funerals.

In 1918 America was caught up in the last horrific year of World War I. Yet the war had nothing to do with the extreme measures being taken. Deadly influenza, the so-called "Spanish-flu," was sweeping the country, spreading terror everywhere.

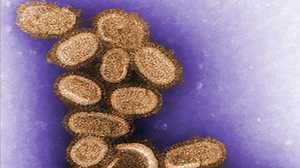

The first documented deaths were in Boston. Explanations were offered, but in fact no one had an answer. Viruses were still largely unknown. But then to this day that particular flu virus is still one of the mysteries of the story.

Once started, the disease moved west in lethal waves that appeared to follow the lines of the railroads. The speed with which it killed was appalling, the loss of life unimaginable. By the time it had run its course in America, the epidemic took more than 600,000 lives.

It would be as if today, with our present population, more than 1,400,000 people were to die in a sudden outbreak for which there was no explanation and no known cure.

It was said every family lost someone. Certainly it seemed that way. I know my own family was no exception. Sarah Cowles, my great aunt--Sarah McCullough before she married--was one of 50,000 cases in Pittsburgh, and one of the 4,500 who died there--in just one medium-sized city.

Could it happen again. Yes, indeed, which is part of the haunting power of this film.

Influenza 1918...

SARDO: People didn't want to believe that they could be healthy in the morning and dead by nightfall, they didn't want to believe that.

NARRATION: It was the worst epidemic this country has ever known. It killed more Americans than all the wars this century -- combined.

REAY: It was a phantom... [PAUSE] We didn't know where it was.

MAXWELL: In a gradual remorseless way, it kept moving closer and closer.

TONKEL: You never knew from day to day who was going to be next on the death list.

FANNIN: There were so many people dying that you ran out of things that you'd never considered running out of before - caskets.

NARRATION: Before it was over, it almost broke America apart.

MILANI: I remember my mother putting a white sheet or a white piece of cloth over his face and they closed the casket...

INFLUENZA, 1918

ACT I: A DEADLY NEW DISEASE

NARRATION: In 1918, the United States was a vigorous young nation, leading the world into the modern age. All our fears and anxieties were directed toward Europe, where the war raged; at home, we were safe. William Maxwell was growing up in Lincoln, Illinois.

WILLIAM MAXWELL: In 1918 Lincoln was a town of 12,000 people. It was perhaps 50 years old, just time enough for the trees to mature so that the branches met over the sidewalks.... Yards were large, the children played in clusters in the summer evenings. On Sunday morning the church bells were pretty to hear. But my father had had enough of church going so we went fishing on Sunday, out in the country with a picnic. It was a life not very much impinged on by the outside world....

NARRATION: In Macon, Georgia, Cathryn Guyler was five years old.

CATHRYN GUYLER: My father was a playmate actually and when he'd take me out in his car, he would stop at, at grocery store that he knew and take me in and the owner of the store, in his white uniform, would say to his men, [CLAPS HANDS] 'Go out and shake the candy tree, boys.'....I think I must have known that candy didn't grow on that tree, but I wouldn't have given up the notion because he was enjoying it and I was enjoying it and everybody was enjoying it, you see.

NARRATION: For a young newspaper woman in Denver, Katherine Anne Porter, life was like a romantic novel.

PORTER: I had a job on the Rocky Mountain News. The city editor put me to covering theaters. I met a boy, an army lieutenant... we were much in love.

NARRATION: The soldier was the darling of America. Patriotism ran unrestrained in a country newly entered in the Great War.

ANNA MILANI: We would march up the streets singin' 'tramp, tramp, tramp the boys are marching. I spy Kaiser at the door. And we'll get a lemon pie and we'll squash him in his eye and there won't be any Kaiser anymore.'

GUYLER: It was a good world, but it was an age of innocence; we really didn't know what was ahead.

NARRATION: Some say it began in the spring of 1918, when soldiers at Fort Riley, Kansas, burned tons of manure. A gale kicked up. A choking duststorm swept out over the land -- a stinging, stinking yellow haze. The sun went dead black in Kansas.

NARRATION: Two days later -- on March 11th, 1918 -- an Army private reported to the camp hospital before breakfast. He had a fever, sore, throat, headache... nothing serious. One minute later, another soldier showed up. By noon, the hospital had over a hundred cases; in a week, 500.

NARRATION: That spring, forty-eight soldiers -- all in the prime of life -- died at Fort Riley. The cause of death was listed as: pneumonia.

NARRATION: The sickness then seemed to disappear -- leaving as quickly as it had come.

NARRATION: For over a century, the booming science of medicine had gone from one triumph to another. Researchers had developed vaccines for many diseases: smallpox, anthrax, rabies, diphtheria, meningitis.

Dr. SHIRLEY FANNIN, Epidemologist: ...With the great advances in microbiology we were eliminating mysteries, okay. The mystery of what causes this disease. The mystery of what causes this disease. The optimism of being able to visualize something... All we have to do is just look under the microscope and we'll see the organism, and then take an action and see that something die off or be controlled.... that leads to the thought of invincibility.

NARRATION: It seemed that the masters of medicine could control life and death: there was nothing that Americans couldn't do. We could even win the war that no one could win.

NARRATION: That summer and fall, over one and a half million Americans crossed the Atlantic for war. But some of those doughboys came from Kansas. And they'd brought something with them: a tiny, silent companion.

NARRATION: Almost immediately, the Kansas sickness resurfaced in Europe. American soldiers got sick. English soldiers. French. German. As it spread, the microbe mutated -- day by day becoming more and more deadly.

NARRATION: By the time the silent traveller came back to America, it had become a relentless killer.

NARRATION: On a rainy day in September, Dr. Victor Vaughan, acting Surgeon General of the Army, received urgent orders: proceed to a base near Boston called Camp Devens.

NARRATION: Devens was about to change Dr. Vaughan's world forever.

READING: I saw hundreds of young stalwart men in uniform coming into the wards of the hospital. Every bed was full, yet others crowded in. The faces wore a bluish cast; a cough brought up the blood-stained sputum.

NARRATION: On the day that Vaughan arrived, 63 men died at Camp Devens.

NARRATION: An autopsy revealed lungs that were swollen, filled with fluid, and strangely blue. Doctors were stunned: what in the name of God was happening to these lungs?

NARRATION: When the strange new disease was finally identified, it turned out to be a very old and familiar one: influenza: the flu. But it was unlike any flu that any one had ever seen.

DR. ALFRED CROSBY, author, "America's Forgotten Pandemic": One of the factors that made this so particularly, frightening was that everybody had a preconception of what the flu was: it's a miserable cold and, after a few days, you're up and around, this was a flu that put people into bed as if they'd been hit with a 2 x 4. That turned into pneumonia, that turned people blue and black and killed them. It was a flu out of some sort of a horror story. They never had dreamed that influenza could ever do anything like this to people before.

NARRATION: Soldiers carried the disease swiftly from one military base to the next. They did it... just by breathing.

FANNIN: If an individual with influenza were standing in front of a room full of people coughing, each cough would carry millions of particles with disease-causing organisms into the air. All the people breathing that air would have an opportunity to inhale a disease-causing organism. It doesn't take very long for one case to become 10,000 cases.

MAXWELL: My first intimations about the epidemic were that it was something that was happening to the troops. There didn't seem to be any reason to think that it would ever have anything to do with us. And yet in a gradual remorseless way, it kept moving closer and closer.

NARRATION: For a time, life in America went on, untouched. Suffragettes demanded the vote for women. Airmail service began zooming between New York and Chicago -- flying time: 10 hours, 5 minutes. On September 11th, Babe Ruth led the Boston Red Sox to victory in the World Series.

NARRATION: But on that same day, on the sidewalks of Quincy, Massachusetts, three civilians dropped dead.

NARRATION: Influenza was out in the world.

ACT II -- IT BECOMES AN EPIDEMIC

NARRATION: From Boston, the disease moved down the eastern seaboard -- to New York, to Philadelphia, and beyond.

MAXWELL: Rumors of this alarming situation had reached this very small town of 12,000 people in the midwest... I know that my parents were worried, I could, I, I paid less attention to their words than I did to the sounds of their voices and when they discussed it, I heard anxiety.

MAXWELL: My mother was expecting a baby and so, my father and mother had no choice, to, but to take me to my father's sister's house where we were not comfortable. It was a dark, gloomy house... I can best suggest the quality of the house by saying, in the living room there was a framed photograph of my grandfather in his coffin.... It was a very strange room, there was a vase with peacock feathers in it and my aunt didn't know, I don't know that anybody else in Lincoln knew that peacock feathers bring bad luck...

DANIEL TONKEL: The first time that I was aware that something was amiss in our normal living was when my father told me, 'son, most of the employees are sick.' We don't have anyone left to run the store. Everyone is home sick, or in the hospital sick. And within a week or ten days my father told me that this saleslady had passed away and another one had passed away. So, as I recall, out of the eight or ten employees, four of them passed away and the passing away came about so quickly.

ANNA MILANI: It was a mild day and we were sitting on the step. Diagonally across from us, there was a little, a girl, 15 year old girl was just buried. Towards the evening, we heard a lot of screaming going on and in that same house a little baby, 18 months old, passed away, in that same family.

FANNIN: For a physician it must have been very, very confusing, being confronted with patients that come to you and, within 12 hours, before you even have a chance to do anything, they're dead. This was happening too fast.

NARRATION: Even children began to see it coming. A little ditty was heard in playgrounds:

I had a little bird/

Its name was Enza/

I opened up the window/

and in flew enza.

NARRATION: Most officials, however, failed to recognize the growing threat.

NARRATION: Royal Copeland, Health Commissioner of New York City, announced, "The city is in no danger of an epidemic. No need for our people to worry." Copeland would let things take their own course.

CROSBY: The first reaction of the authorities was, for many of the most important ones was just flat-out denial. They didn't know what was happening, they didn't know what to do and, therefore, they did the human thing which is to say it's not happening.

NARRATION: With the war escalating, federal officials continued to put Americans at risk. One September day, they called 13 million young men to register for the draft. The men jammed together in school houses, city halls, post offices.

CROSBY: There were two enormously important things going on at once and they were at right angles to each other. One, of course, was the influenza epidemic, which dictated that you should sort of shut everything down and the war which demanded that everything should speed up, that certainly the factories should continue operating, you should continue to have bond drives, soldiers should be put on boats and sent off to, sent off to France.... It's as if we could, as a society, only contain one big idea at a time and the big idea was the war.

NARRATION: With America's tunnel vision focused on the war, throngs turned out for enormous parades supporting Liberty Loan drives.

NARRATION: In Philadelphia, 200,000 sardined in the streets. The crowd linked arms, sang patriotic songs -- breathed on each other -- infected each other.

NARRATION: And in the days that followed, the flu ripped into Philadelphia like a freshly-sharpened knife.

NARRATION: Harriet Ferrell's family lived on Brooklyn Street.

FERRELL: It was really a terrible experience for the people, it was so many people sick. In our household, it was the four of us in bed and my uncle and aunt on the third floor apartment with their son, so my mother was caring for seven sick people in our home.

CATHRYN GUYLER: When my mother became ill, that's when I knew we were in trouble. I only knew it from my child's eye and my child's eye was five years old. I wanted to go and get in her bed and it wasn't allowed, they didn't want me to get sick either, do you see. And they brought in a little bed into her room. My mother saw me miserable in that little bed, that they brought in for me and tucked me in her bed because she didn't like to see me unhappy. And, of course, I promptly got the flu with her, as you could imagine and there was fun in that for me until it became so painful.

WILLIAM MAXWELL: I was a skinny little boy with an enormous appetite. Just as my plate was put in front of me, I felt no desire for food. My aunt put her hand on my forehead and got up from the table and took me upstairs and put me to bed because I had a high fever. And I think what happened was that I slept and slept and slept and slept.

NARRATION: No one knew what was causing the epidemic; but there was no shortage of guesses.

WILLIAM SARDO: There were rumors that ran rampant of all types and sizes and one of the rumors, I remember very explicitly, was that the Germans had planted the germ before the spread of influenza.

NARRATION: Flamboyant evangelist Billy Sunday thought the cause was as simple as sin. "We can meet here tonight and pray down the epidemic," Sunday said. But even as he spoke, people in the audience collapsed with the flu.

NARRATION: One agonized official in the stricken east sent an urgent warning west.

NARRATION: Hunt up your wood-workers and set them to making coffins. Then take your street laborers and set them to digging graves.

NARRATION: The flu was now moving into small towns, deep in the heart of the country. Lee Reay was living in Meadow, Utah.

LEE REAY: We were very concerned in our town, it was moving south, progressing down the highway, and we were next... My father was selected as the health officer. We had never had a health officer in our town before, but we felt now that we needed one and so Dad went out to the city limits signs, and we put a sign that said, THIS TOWN IS QUARANTINED - DO NOT STOP. So we had purposely isolated ourselves. But it wasn't enough, the disease came anyway - the mailman brought it.

FANNIN: You can't barrier yourself from being exposed, because the person who looks healthy may be the one spreading the disease. And that was a part of the horror. We can't get away from respiratory diseases of other people, because we all have to breathe.

NARRATION: In Denver, Katherine Anne Porter's romance was cut short; she too became sick. Soon, she was delirious.

NARRATION: But Porter's dashing young lieutenant stayed by her side.

PORTER: He was so patient with me, those nights when I was sick, getting me things and always just sitting there. When I would wake up he would be there...

NARRATOR: Her fever rose so high that her hair turned white, then fell out.

PORTER: There was only that pain, only that room. There was only this one moment and it was a dream of time.

MAXWELL: I remember that time was a blur as I was lying in that little upstairs room and I would wake up and it would be daylight and I'd wake up, the next time I woke up it would be dark and it might be dark when I woke up, it might be daylight, I had no sense of day and night. And I felt sick and hollow inside.

ACT III -- THE RESPONSE

VOICES OF CHILDREN:

I had a little bird/

Its name was Enza/

I opened up the window/

and in flew enza.

NARRATION: And In flew enza.

NARRATION: Hospitals overflowed; emergency relief centers sprang up in parks and playgrounds. But practically every available doctor and nurse had been sent to Europe. The ones who remained were asked perform the impossible. Near Chicago, a young nurse named Josie Mabel Brown arrived at Great Lakes Naval Station -- and was promptly assigned a ward with 42 beds.

MORRISSEY: She walked into the ward and not only were the 42 beds full, but there were boys that were laying on the floors and on the stretchers waiting for that boy in the bed to die. They were having raging fevers and delirium and profuse nose bleeds and their lungs would collapse and it would go into this horrid, bloody pneumonia.

CROSBY: When the 1918 flu killed, which it so often did, it killed because of what it did to the lungs. It filled up the lungs with fluid, and so these people, these people drowned, only they didn't drown in the Atlantic Ocean, they drowned in their own fluids.

NARRATION: The epidemic was now a national crisis: something had to be done.

NARRATION: In many places, officials rushed through laws requiring people to wear masks in public.

NARRATION: All of America, it seemed, put on masks. At last, many thought, they were safe.

NARRATION: But masks didn't help. They were thin and porous -- no serious restraint to tiny microbes. It was like trying to keep out dust with chicken wire.

NARRATION: In Washington, D.C., Commissioner Louis Brownlow banned all public gatherings. He closed the city's schools, theaters and bars. He quarantined the sick. He did everything he had the power to do.

NARRATION: But the death rate in Washington kept rising.

NARRATION: A resolution shot through Congress, giving the Public Health Service a million dollars to fight the flu. Biochemists around the country worked feverishly to develop a vaccine. Hundreds were produced. Then, a researcher in Massachusetts came up with the most promising solution. Hopes rose: perhaps a cure was at hand. San Francisco's mayor wired for a huge shipment; a special envoy carried the vaccine across the country on the fleet Twentieth Century Express. Soon over 18,000 people in the city had been

inoculated.

NARRATION: But even vaccines didn't help.

FANNIN: They thought it was caused by a bacteria, so they made up a vaccine with the bacteria they thought was influenza.... But, you can't make a vaccine if you're looking at the wrong causative organism. They were on the wrong track; the influenza was caused by a virus.

CROSBY: Science knew next to nothing about viruses at this time. The optical microscopes they had couldn't show you a virus, virus is much too small for them. Nobody would ever see virus until the electron microscope came along and that was decades after that. These poor scientists were looking for a needle in a haystack, when they didn't know it was a needle they were looking for and the needle was too small for them to see. No wonder they didn't find it.

NARRATION: Medical science, at the very moment of its great rise to power, had failed to provide a cure.

READING: At that moment I decided never again to prate about the great achievements of science... The deadly influenza demonstrated the inferiority of human inventions. Victor Vaughan.

NARRATION: With science powerless, many people turned to folk remedies and quick fixes.

SARDO: There was some quackery that existed at the time. There were all kinds of, of gimmicks that were being pursued by people in desperation.

JOHN DE LANO: I had camphor balls in, in a little sack around my neck. I know I couldn't stand myself, let alone somebody coming near me. [LAUGHING] I smelled so bad, I guess, in those days.

FERREL: We used turpentine on sugar, we used kerosene on sugar, a few drops... you could smell this medication before you got too close to them, but it wasn't too bad because so many people had these different type medications until we were all smelling bad.

REAY: Everybody was asking for medicine and there wasn't any. So Dad came home and said, "We've got to make medicine some way." And so in our kitchen, on our cookstove, Dad stewed up about five gallons. It wasn't real medicine, but it smelled like medicine and it tasted like medicine and we put a lot of honey in it so that it would taste pretty good and we passed it out to everyone who wanted medicine. It went in a hurry, there wasn't much left. [CHUCKLING] It didn't do any harm. Most of them thought it did good.

CROSBY: In the middle of a crisis you have to do something and it's certainly an American characteristic that we have to do something even if it's wrong.

NARRATION: Folk remedies might have been wrong, but doctors were just as helpless.

MORRISSEY: They absolutely didn't know what to do for treatment of these patients. The ambulances would arrive in the morning, the drivers would bring in four living patients, but the nurses would go ahead and wrap these patients in the winding sheets and they would put toe tags on the boys before they were even dead.

NARRATION: One doctor told a patient's wife: "This is my twenty-fifth case. And I've lost the first twenty-four."

NARRATION: A twelve-year-old boy was told by his doctor: "Get on the waiting list for a casket."

FERRELL: My mother called a doctor because we, the whole family was sick with this flu, and I, being the infant baby, was very sick, to the point that the doctor thought that I would not make it and he told my mother that it wasn't necessary to feed me anymore because I wasn't going to live.

ACT IV -- THE HORROR

NARRATION: In the month of September, some 12,000 people died of influenza in America. But those numbers would be dwarfed. For the full horror now began. October would be the cruelest month.

MILANI: In the street, there were crepes at the door, if it was a young person they put a white crepe at the door; if it was a middle aged they put a black and if it was an elderly one, much older, they put a grey crepe at the door, signifying who died. So, there were, we were children and was, we were excited to find out who died next.

SARDO: My father, my older brother and an uncle were all engaged in the funeral directing business....We lived in a funeral home. The influenza epidemic became so bad that the living room, the dining room were all occupied with row upon row of caskets. The fearsome part of it was that these were friends of yours that were passing away, these were whole families that you knew, these were people that you went to school with or church with. It was very eerie, very, very eerie.

DELANO: The undertaker which was half a block away from me had pine boxes on the sidewalk, piled high. Me and my two friends would go down there and play on the boxes, it was like climbing the pyramids, up and down and around, the whole bit jumping off, and my mother told me that I should never go down there, don't go on those boxes because there are people in them that have died. But these two friends of mine got sick right after that -- and so did I.

REAY: My father, being the health officer, was very concerned about the Indians who were our neighbors, they were only six miles away. So Dad and the city marshall rode up there one day to see how things were going at the Indian camps and they were horrified at what they saw. After an Indian died, his family and friends would sit around chanting him to the Happy Hunting Grounds and they'd spend all night there. And, by that time, they were all exposed, everybody had the flu. Ultimately, it killed about half the Indians.

NARRATION: No one was safe. In Washington, Victor Vaughan was working late, trying to make sense of the hellish chaos. He uncovered an unnerving fact. Usually, influenza kills only the weak -- the very young and very old -- but this time it had a different target. People in the very prime of life -- from 21 to 29 -- were the most vulnerable of all.

READING: Victor Vaughan: "This infection, like war, kills the young, vigorous, robust adults.... The husky male either made a speedy and rather abrupt recovery or was likely to die.

CROSBY: The situation was upside down and backwards, a disease that's supposed to be a mild disease is killing people, the people it's killing are the strongest members, the most robust, members of our society.

NARRATION: For example: soldiers. In Europe, the flu was devastating both sides. Seventy-thousand American soldiers were sick; in some units, the flu killed 80% of the men. General John Pershing made a desperate plea for reinforcements. But that would mean sending soldiers across the Atlantic on troop ships.

CROSBY: There's nothing more crowded than a troop ship, it's just being jammed in there like sardines and if somebody has a respiratory disease, everybody's going to get it.

NARRATION: President Woodrow Wilson now faced an agonizing decision. Sending the soldiers would be signing thousands of death warrants. Wilson gazed out his office window. After a long moment, he nodded. The troop shipments would [have to] continue. And then the President turned to his aide. "I wonder if you have heard this limerick?"

'I had a little bird and his name was Enza...'"

READING: I lay like a stone at the farthest bottom of life. The smell of death was in my own body.

NARRATOR: Katherine Anne Porter was finally admitted to the hospital. But she was now separated from her lieutenant. She was so sick that she was left on a stretcher in the hallway -- left there to die. Porter's newspaper quietly set the type for her obituary.

NARRATION: In New York, 851 people died of the flu in a single day. But the greatest horror came to Philadelphia. In one week in October, the death rate there was seven hundred times higher than normal.

MILANI: In October we were all stricken, we were all sick. We had headaches, pains in the legs, the stomach, vomiting and everything. We were all sleeping close to one another because we only had two beds in the one room..... Harry couldn't stay with us because he was too sick...I was like a second mother to Harry, Harry was always close to me.... So, when he was very sick he kept calling me all the time and... I was always beside him and I would cuddle him and pet him and everything... So my mother said while Harry's sleeping, you go and lie down... And my mother said he, he opened his eyes, his eyes went back and forth and his head went back and forth and he said, "Annie." My name was Nanina, in Italian, Nanina, Nanina and he died with my name in his mouth....

NARRATION: In Philadelphia, death carts roamed the city. It was a scene

from the time of the Black Plague.

FERREL: So many people died until they were instructed to ask for wooden boxes and to put the corpse, the people on the front porches. An open truck came through the neighborhoods and picked up the bodies.

NARRATION: Still, the dead sometimes lay in the gutters, abandoned.

NARRATION: Over at Potter's Field, they began to use a steam shovel to dig trenches. For graves. Mass graves.

NARRATION: Over 11,000 people would die in Philadelphia alone that October.

NARRATION: In Illinois, William Maxwell's mother had just given birth. He was still staying at his aunt's house.

MAXWELL: My only knowledge of what was going on was the telephone which I could hear from, because my room was at, near the head of the stairs. And I heard my aunt say, 'Will, oh no.' And then, 'If you want me to.' And she came into my room and she tried to tell us what had happened and the, the tears ran down her face and so she didn't need to tell me, I knew that the worst that could happen had happened. My mother was marvelous, and when she died the shine went out of everything.

NARRATION: In 31 shocking days, the flu would kill over 195,000 Americans. It was the deadliest month in this nation's history.

NARRATION: Coffins were in such demand that they were often stolen. Undertakers had to place armed guards around their prized boxes.

NARRATION: The orderly life of America began to break down.

NARRATION: All over the country, farms and factories shut down -- schools and churches closed. Homeless children wandered the streets, their parents vanished.

NARRATION: The vibrant and optimistic nation seemed to be falling apart.

TONKEL: People were actually afraid to talk to one another, it was almost like don't breathe in my face, don't look at me and breathe in my face because you may give me the germ that I don't want, and you never knew from day to day who was going to be next on the death list.

SARDO: Everybody was living in deadly fear because it was so quick, so sudden and so terrifying it destroyed the intimacy that existed amongst people in those days of the early 20th century.

CROSBY: An epidemic erodes social cohesiveness because the source of your danger is your fellow human beings, the source of your danger is your wife, children, parents and so on. So, if an epidemic goes on long enough, and the bodies start to pile up and nobody can dig graves fast enough to put the people into them, then morality does start to break down.

NARRATION: Violence broke out. In San Francisco, a Health Department inspector shot a man who refused to wear a mask. In Chicago, a worker shouted, "I'll cure them my own way!" and then cut the throats of his wife and four children.

DR. FANNIN: People were surrounded by traumatic death. And they didn't have any idea how far it would go. Was it going to kill everybody?... Could this be the end of the world - is this armageddon that the street corner ministers are preaching about?

NARRATION: In Washington, Victor Vaughan came to a frightening conclusion.

VICTOR VAUGHAN: If the epidemic continues its mathematical rate of acceleration, civilization could easily disappear from the face of the earth.

ACT V -- IT'S OVER

NARRATION: But a miraculous thing began to happen. As mysteriously as it had come, the terror began to slip away. By early November, the flu had virtually disappeared from Boston; the toll in Washington fell below 50 a week; even in ravaged Philadelphia, life was slowly returning to normal.

NARRATION: Then, on November 11, the Armistice ended The Great War. In San Francisco, the scene was surreal. Thirty thousand people paraded through the streets -- all dancing, all singing, all wearing masks. The country had a lot to celebrate -- not only was the war over, but the worst of the epidemic was passing.

DR. FANNIN: In light of our knowledge of influenza and the way it works, we do understand that it probably ran out of fuel, it ran out of people who were susceptible... it's like the firestorm, it sweeps through and it has so many

victims and the survivors developed immunity.

NARRATION: But for some survivors, like Katherine Anne Porter, the return of health was not the end of pain. Her dashing lieutenant, who had faithfully tended her, was suddenly dead himself -- of influenza.

NARRATION: The lieutenant's death, Porter later said, divided her life in two.

PORTER READING: It was one of the most terrible things that ever happened to me -- that he should have died and I should have lived. He died... And it seems to me that I died then.

DELANO: And then when we got out again and went back to school, I was shocked to see that my friends were not around, they weren't home. I would knock on their door and they would open the door just a little bit and says, "No, Jimmy's not here" or "Frankie's not here." or, and, "Where is he?" "Let your mother tell you." They wouldn't tell me, "Let your mother tell you." I was a pretty lonely kid at the time because these were my friends that I played with all those years, and went to school with and when I lost them, why, my whole world changed.

CROSBY: The epidemic killed, at a very, very conservative estimate, it killed 550,000 Americans in ten months, that's more Americans than died in combat in all the wars of this century, and the epidemic killed at least 30 million in the world and infected the majority of the human species.

NARRATION: As soon as the dying stopped, the forgetting began.

CROSBY: It is in the individual memory of a great many of us, but it's not in our collective memory. That, for me, is the, is the greatest mystery: how we could have forgotten anything so horrendous, so massively horrendous, as this, this epidemic which killed so many of us, killed us so fast and our reaction was to forget it.

FANNIN: Why? Why wasn't that part of our memory? Or of our history. I think it's probably because it was so awful while it was happening, so frightening, that people just got rid of the memory. But it always lingers there. As a kind of an uneasiness. If it happens once before, what's to say it's not going to happen again. The more we find out about influenza virus, the more real that fear becomes.

NARRATION: The fall of 1918 was a time of horror, a time to forget, but some would always remember.

MILANI: I remember my mother putting a white sheet or a white piece of cloth over his face and they closed the casket... I can't forget. It was very, very bad.

MAXWELL: The effect of my mother's death was that I realized, for the first time and forever, that we were not safe, we were not beyond harm. My father did what he could, he kept us together as a family but, from that time on there was a sadness, which had not existed before, a deep down sadness that never quite went away because, I knew people aren't safe and nobody's safe —terrible things could happen — to anybody.