Narrator: In the early morning hours of March 29th, 1914, deep in the Amazon rainforest, former American president Theodore Roosevelt, wracked with fever, summoned his son Kermit to his tent. After traveling an uncharted river in Brazil for over a month, Roosevelt was too weak to continue. He told his son to go on without him.

Clay Jenkinson, Historian: Roosevelt says, “This is it. Either we all die, or I die and you all get out. Obviously there’s no choice. You have to leave me here.”

Louis Bayard, Author: He had conquered so much. He had conquered every challenge that came his way. But now, for the first time, this force of nature has to bow down to nature’s force.

Narrator: Theodore Roosevelt was now one of 21 men lost in one of the last unexplored regions on Earth - facing crippling disease, perilous rapids, and a jungle alive with threats.

Tweed Roosevelt, Great Grandson: The Americans thought, in the middle of the night, the Indians could come in and slit your throat.

Jenkinson: The Amazon jungle eats whatever comes its way. That whole environment consumes whatever moves through it.

Narrator: No one knew where the river might lead, or when their ordeal would end. But one thing was certain - their fate was in the hands of Brazilian explorer, Cândido Rondon.

Roosevelt: Rondon was tremendously experienced. Col. Rondon was essentially the Brazilian equivalent of Lewis and Clark.

Larry Rohter, Rondon Biographer: Rondon knows he’s got to get Teddy Roosevelt out of the jungle safe and sound. He can’t have the President of the United States dying on him in the middle of the jungle. Don’t let him die.

Act One

TR VO: There yet remains plenty of exploring work to be done in South America, as hard, as dangerous, and almost as important as any that has already been done. But the true wilderness wanderer must be a man of action as well as of observation. He must have the heart and the body to do and to endure, no less than the eye to see and the brain to note and record.

“Day 1”

Narrator: On January 21st, 1914, in the most remote section of the Amazon rainforest, former President Theodore Roosevelt and his son Kermit set off on a joint American-Brazilian expedition. Their mission was to chart a mysterious river known only as the “River of Doubt.”

Snaking its way through a nearly impenetrable rainforest, the river was a tantalizing prize for any would-be explorer, and Theodore Roosevelt hoped to put it on the map.

Just 15 months earlier, in November of 1912, Roosevelt had suffered a crushing political defeat after he lost his bid for a third term as president. Wanting to put the election far behind him, he accepted an invitation from the Brazilian government to explore the least-known region of the Amazon.

“No civilized man, no white man,” Roosevelt wrote, “had ever gone down or up this river...”

Kathleen Dalton, Historian: Theodore Roosevelt has a real fascination with explorers - explorers who risk their lives to open up unknown lands, men who risked their lives to advance civilization.

Rohter: There is the adventure part of it. It was a kind of test: am I tough enough?

Jenkinson: There was something in Roosevelt’s character that required him to take on challenges, however risky they might seem. So for Roosevelt suddenly to get this, sort of, last little glimpse of the true Age of Exploration was simply too alluring for him to turn down.

Narrator: In order to reach the River of Doubt, the expedition would first need to trek nearly 400 miles across the broad savannas and tropical forests of the Brazilian state of Mato Grosso.

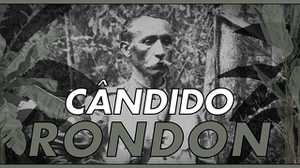

Guiding Roosevelt and his six-man American team was a 48-year-old Brazilian army officer and part Amazonian Indian, Colonel Cândido Rondon.

Though he stood just five feet three inches tall, Rondon was a formidable figure. He’d spent over a decade laying miles of telegraph wire deep into the interior of the rainforest. And he knew more about the Brazilian Amazon than any man alive.

Todd Diacon, Historian: Rondon built 2,000 miles of telegraph line, 1,000 miles of it through a swamp, and 900 miles of it through the jungle.

Roosevelt: Rondon was tremendously experienced. Colonel Rondon was essentially the equivalent - the Brazilian equivalent of Lewis and Clark.

But just as Colonel Rondon began leading the men to the river, it became clear that the expedition had a problem.

The Americans had arrived with a mountain of baggage - hundreds of crates, stuffed with collecting jars, camera equipment, and comforts from home, like bacon, wine, and chocolates - provisions that were never meant to be hauled overland through the wilderness.

Roosevelt and his men had originally planned a simple hunting and collecting trip along the much-traveled Paraguay River. But after arriving in Brazil, Roosevelt changed the itinerary. He accepted an offer from the Brazilian government and Colonel Rondon to take on the much more dangerous River of Doubt expedition.

Jenkinson: When the journey changed at Rio, a lot of the things that they had anticipated, and much of the equipment that they had brought, was no longer particularly useful. It was too bulky. The gear that the Americans brought with them was for a different sort of trip.

In order to transport the expedition’s cargo, Colonel Rondon hired over 140 men - a mix of Brazilian soldiers, cowboys, and peasants he called “camaradas,” the Portuguese word for comrades. And he spent days rounding up hundreds of pack animals.

Rondon VO: The organization of this baggage train with a cargo of 360 large packages, besides many smaller ones, took five days of incessant toil. I had managed to bring together 110 mules and 70 oxen. The mule procured for Mr. Roosevelt was a strong animal with a smooth walk.

To the Brazilians, the most puzzling pieces of gear were the Americans’ 19-foot canoes, which would have to be dragged hundreds of miles before they could even be launched down the river.

Diacon: The idea that you would bring a canoe - why would you bring a canoe? And the Brazilians, they just made their own canoes. They made dugout canoes. You just, you cut down trees and you fashion your own canoes. Rondon was perfectly comfortable and greatly experienced in living off the land. So from the Brazilian standpoint, it was like, what are we supposed to do with all of this, all of this equipment? These trunks full of material? This baggage?

The effect of Roosevelt’s last-minute decision to change plans was immediate. Exhausted pack animals, now straining under the weight of the American baggage, began to buck their loads along the trail. Roosevelt and his men could only walk past and wonder what essentials were being left behind.

Jenkinson: They see one piece of equipment after another being tossed aside on the trail and they’re beginning to think – whoa, what’s going to be left when we get to the headwaters of this river? But what Roosevelt wanted was to test himself against nature and to be on the edge of danger and to really rough it.

With each passing mile, the expedition was moving farther from civilization and closer to the edge of the frontier, into a land that would test the limits of their endurance and a river that would carry them deep into the unknown.

The Amazon Exploration

Narrator: Theodore Roosevelt came of age in an era of great exploration, when adventure-seeking men risked their lives competing for the Earth’s rarest geographical prizes.

In 1909, Americans Robert Peary and Matthew Henson won the race to the North Pole. Two years later, in 1911, Roald Amundsen planted Norway’s flag on the South Pole. And in 1914, the year Roosevelt left to find the River of Doubt, Sir Ernest Shackleton nearly died trying to cross the Antarctic.

But the Amazon rainforest, which spread like an enormous green drape across a third of South America, had largely remained a mystery to western explorers.

Sydney Possuelo, Explorer and Former President of FUNAI: The Amazon of 1913, was a very unknown region - the great wilderness, the empire of remoteness, of distance. So it was a region full of mysteries. All this would feed people’s imaginations. It’s as if you were in the middle of the sea, a sea filled with monsters, dragons and monstrous beasts. I mean, these are the myths of the Amazon.

Rohter: The Amazon always has this, kind of, aura of mystery about it. You know, who lived there? What were they like?

Narrator: Since its earliest European explorers of the 16th century, the Amazon had been the stage for mythmaking. One of the most enduring involved an ancient civilization known as El Dorado, with wealth so great, it was said the king would coat himself in gold.

Rohter: For centuries you have people convinced that there’s some hidden city and it’s always around the next bend. And nobody can ever find it.

Narrator: The search for El Dorado claimed the lives of whole expeditions - wiped out by disease, starvation, and Indian attack. Those who survived emerged with harrowing tales of a vast wilderness teeming with exotic species - like jaguars, man-eating piranhas, and giant caiman.

Cannibals were said to roam the interior in search of human prey, while Amazonian women warriors stalked the forest and river banks.

Rohter: These myths carried over into the 20th century.

Possuelo: I think that some regions of the world are favorable for myths, for creating heroes. To get there took great effort, fortitude, and a large amount of personal strength. This was the Amazon when Roosevelt came here.

Roosevelt’s Mission “Day 6”

TR VO: We were now in the land of the bloodsucking vampire bats that suck the blood of the hand or foot of a sleeping man. South America makes up for its lack of large man-eating carnivores by the extraordinary ferocity of certain small creatures, bats the size of mice, fish no bigger than trout kill men. Genuine wilderness exploration is as dangerous as warfare. The conquest of wild nature demands the utmost vigor, hardihood, and daring, and takes from the conquerors a heavy toll of life and health.

Narrator: By January 26th, the expedition was marking slow progress having covered less than 75 miles in a week. Colonel Rondon estimated there was still over a month of travel ahead, just to reach the headwaters of the river. To make better time, Rondon made the decision to cut the midday meal, which meant they would sometimes ride for 12 hours without eating.

During the day-long marches the expedition was subjected to the 100 degree heat and insufferable tropical humidity that left all the men drenched in sweat and some of the Americans on edge.

Father John Zahm, an elderly Catholic priest and old friend of Roosevelt’s, complained incessantly about the conditions on the mule train.

An amateur explorer himself, Zahm had been in charge of organizing Roosevelt’s original Brazilian itinerary, which he promised the president would be “as easy as a promenade down Fifth Avenue.” Now, the priest found himself on a very different trip, struggling to keep pace in an unforgiving rainforest.

Even for a seasoned explorer, like the American naturalist George Cherrie, the expedition appeared to be off to an unsteady start.

Cherrie VO: The organization and management of our outfit is not the best. We would plan to make an early start but we usually ride through the hottest part of the day. It is hard on us and even harder for our animals.

Roosevelt: When TR went on these kinds of expeditions - when he could, he took naturalists with him. George Cherrie had worked as a collector for some of the great American museums. He was kind of the preeminent collector of the time. Fascinating fellow - kind of an Indiana Jones-type.

Narrator: At night, when the temperatures dropped and the mood of the expedition lightened, the men bonded over stories of their past exploits.

George Cherrie shared wild tales of running guns for Venezuelan rebels while on collecting trips through Latin America. The American provisioner Anthony Fiala, who had once been marooned for a year in the Arctic, told of hunting polar bear to survive. And Colonel Rondon shared grim memories of surviving the very wilderness that surrounded them on nothing more than fruit and honey stolen from beehives.

But nobody could top Theodore Roosevelt’s stories.

Dalton: TR - he’s a great raconteur, and very funny and charming. He’s full of these interesting stories - his Africa story, his wild west stories. And every story - always he’s the hero, he’s brave, he faces hardships, and he conquers.

Narrator: By 1914, 55-year-old Theodore Roosevelt was a living icon of outdoor adventure and manliness.

He’d written 35 books, many of them colorful yarns about his experiences in war and hunting big game across the globe.

When he left the presidency in 1909, Roosevelt wrote a best- selling book about his year-long safari in Africa.

He’d hoped to do the same in Brazil, signing a deal with Scribner’s Magazine to tell the story of his journey.

But this carefully crafted romantic image of the indomitable adventurer was born of a childhood filled with physical challenges and personal tragedy.

As a young boy, Theodore Roosevelt was stricken with asthma - an illness that gave him little control over his own world and left him too weak to take part in sports and the outdoor adventures of youth.

Dalton: To understand Theodore Roosevelt you have understand his struggle against illness as a child. Theodore Roosevelt almost died many times from serious asthma. And his father had to walk him at night to help him breath.

Jenkinson: When he was about 12 years old, his father said, “Your mind is strong, but your body is weak. Son, you must make your body.” And really by sheer force of will, Theodore Roosevelt did it.

Narrator: As Roosevelt grew older, nature became his proving ground, where he rebuilt his body through what he called “the strenuous life”. In the outdoors he could test the limits of his endurance through epic hikes, camping trips, horseback riding, swimming, and hunting.

Dalton: It’s clear that this childhood of asthma haunted him - that invalid self is haunting him, and he’s going to fight it with every means possible. It’s hunting, shooting, climbing, running, rowing, boxing. This is a guy who likes physical danger and feels more alive around physical danger.

Narrator: By the age of 23, Roosevelt was taking the world by storm. He had overcome his childhood illnesses and was now a robust young man. He entered politics and won a seat in the New York State Assembly. And he married his great love Alice Hathaway Lee, who was soon expecting their first child.

But on the night of February 14th, 1884, Roosevelt’s world came crashing down. He rushed to his family’s Manhattan townhouse, where Alice was on the brink of death after having given birth. And just down the hall, his beloved mother Martha was slowly succumbing to typhoid.

Jenkinson: The two most significant women in Roosevelt’s life died more or less simultaneously, in the same home, on the same day, Valentine’s Day 1884. Theodore Roosevelt had a little 2-by-3-inch diary. And in it, he made a large “X” and said, “The light has gone out of my life.”

Narrator: Roosevelt left politics and fled to the North Dakota Badlands to work as a cowboy, seeking the solitude and vindication of life in the wild.

Roosevelt: Now, this was very hard for him. And there are stories of some of his ranch hands or others hearing him at night, pacing up and down, and essentially crying for his lost wife.

Narrator: In the Badlands, Roosevelt sought to transform himself once again, driving cattle, chasing rustlers, and risking his life in order to overcome the pain of his loss through relentless physical toil.

Jenkinson: Something about that experience - that frontier reinvigoration, living the life of Daniel Boone and Davy Crockett - propelled him into a sort of heroic persona. Now he was a cowboy. He was a big game hunter. He was a man known for strenuous adventures.

Narrator: From that point on, Theodore Roosevelt was in near constant motion. “Black care,” he famously said, “rarely sits behind a rider whose pace is fast enough.”

Bayard: That was his way of dealing with psychological stress - to embark on this very physical, very intense lifestyle. Keep moving. His idea is that if you just keep moving that sadness can’t catch you.

A Mission for a Son “Day 11”

TR VO: Rain is coming down more heavily than ever with no prospect of cessation. It is not possible to keep the moisture out of our belongings; everything becomes moldy except what becomes rusty. The very pathetic myth of "beneficent

nature" could not deceive even the least wise if he once saw for himself the iron cruelty of life in the tropics.

Narrator: By early February, the expedition was into the second week of its journey and had traveled nearly 100 miles deeper into the wilderness, but despite making better time, they were still nearly 200 miles from the headwaters of the River of Doubt. Traveling the Amazon wilderness was turning out to be far more difficult than Roosevelt and the Americans anticipated.

Flying insects followed them like clouds of smoke. Bloodsucking sandflies and sweat bees were a constant nuisance. Even with head nets and gauntlet gloves, there was no escape from the mosquitoes.

At night termites and ants invaded their camp, eating their books and journals, and even Roosevelt’s underwear.

Rohter: Every parasite under the sun. You know, worms in the belly. The bugs constantly biting. The way they flock on your face and, you know, try to drink the sweat and the tears in your eyes. I mean, it’s just maddening.

Jenkinson: The Amazon jungle eats whatever comes its way. There’s just a way in which the insects, and the bacteria, and the worms, just that whole environment just sort of consumes whatever moves through it.

Malaria and dysentery were racing through the expedition, and many of the camaradas were already ill. Now, Roosevelt’s son, Kermit, had become sick, and his fever spikes seemed to grow worse by the day.

Bayard: Kermit is literally sitting in his saddle, shaking and feverish. Abscesses grow along his nether quarters, just from all the jostling of riding there. It’s extremely painful.

Narrator: 25-year-old Kermit Roosevelt, the second son of Theodore and Edith Roosevelt, had put his life on hold in order to accompany his father into the Amazon. He was in love with a young socialite named Belle Willard, who had just recently accepted his marriage proposal.

Bayard: Kermit is longing for this woman who has just committed to being his wife. He wants more than anything to be by her side, and the deeper they go into this jungle, the further it takes him away from her.

Dalton: Kermit did not want to accompany his father. He was trying build his own life. He was trying to not be just the great man’s son.

Bayard: Kermit was very different from the other Roosevelt children. He was quiet. He was sensitive. He was moody. He would retreat to himself for long periods of time. His mother used to say that he was the child with the white head and the black heart. The white head because he was the blondest of the Roosevelt children, but the black heart because from earliest childhood was beset with melancholia. So, he is the one who has to travel the furthest distance to be like his father.

Jenkinson: Roosevelt required, even forced his children, to get over whatever shyness, and timidity, and fears that they might have. He believed that it was part of character building that you face your fears and you work through them.

Narrator: In 1909, Kermit joined his father on safari in Africa, where he spent an entire year hunting big game alongside the ex-president.

Jenkinson: Safari in Africa was the first time when they really got to be alone for an extended period, and what Roosevelt noticed was, first of all, that his son was good to be around. He liked him. He was a good companion. Secondly, he noticed that Kermit had overcome whatever timidities he had had as a child.

Narrator: The bond the two men forged in Africa convinced Edith that her son Kermit could look after his father in the Amazon.

Edith was worried that ever since her husband had lost his bid to regain the presidency, he had been in a reckless frame of mind.

Dalton: Theodore Roosevelt was in a deeper despair than Edith had ever seen him be in before. Edith needs somebody who knows the kind of danger he will invite. He’s in a dangerous mood. She wants Kermit to go with him. Okay, he can have a little heroism, but she wants him back. She wants him to survive this trip. Edith knows Kermit adores his father, and could pull him out of bad situations.

Kermit VO: Dear Belle, We keep crawling along, gradually cutting down the distance to the river, but oh so very slowly; I have hated the trip and feel miserable being so far from you. If I hadn't gone, we'd have both always had it in the back of our minds, that it was my only chance to have helped father out, and mother too,... Mother is dreadfully worried... There was nothing for me to do but to go... Kermit.

Rondon’s Mission “DAY 28”

Narrator: From the beginning of their journey, the expedition had been following a path through the wilderness carved by Cândido Rondon more than a decade earlier. In 1900, Colonel Rondon had been commissioned by the Brazilian government to build a telegraph line into the interior of the rainforest.

But after a month of travel, the men were now crossing into a land where only Rondon and a handful of outsiders had ever traveled.

TR VO: We are now entering the land of the naked Nhambiquara Indians. Nowhere even in Africa did we come across wilder more absolutely primitive savages. They are not warlike as the Iroquois or Sioux, though there are vicious ones among them, what the traveler has to be afraid of is their fear of him.

Rohter: The Nhambiquara. They didn’t even really have houses. They slept on the ground. They used arrows. They used slingshots. I mean, it was a shock to the Brazilians themselves. So to the Americans, it would've been ever more so.

Jenkinson: There was almost an Adam and Eve-like innocence about them. It was an entirely naked tribe. Roosevelt said they were naked but they never exchanged lascivious looks. There was no sense of shame. They were fascinated by him, especially when he was writing, and they would move in towards Roosevelt. Writing must have seemed like a form of magic to them, and Roosevelt said that he actually had to sort of gently push them away from him.

Narrator: Rondon had established an easy rapport with the Nhambiquara. He played games with their children and conducted business with the elders, trading axe heads and jewelry for manioc flour and other supplies.

But the good will between Rondon and the tribe had not come easily.

Like most Amazonian Indians, the Nhambiquara had only encountered white men who were looking to convert them to Christianity, or exploit them as slave labor for the rubber industry.

Years earlier, when Rondon first entered their land, the tribe had nearly killed him.

Diacon: He heard a fluttering sound, then an arrow stuck in the strap of his cartridge belt. His men were all gathered, planning a counter-attack, and he says, “No, we’re not going to do this. This is not our approach.”

Narrator: Rather than counter-attack, Rondon created his own method to engage with Indian tribes.

Joseph Ornig, Author: Colonel Rondon had an old Victrola and he had some Caruso records, and in order to tempt these Indians to come into his camp, he’d play this music. They couldn’t resist it.

Mércio Gomes, Anthropologist and Former President of FUNAI: Rondon thought the Indians should be treated with kindness. They have been violent because people have been violent to them. If you are not violent to them, they will be kind to you.

Narrator: During his telegraph missions, Rondon had made first contact with dozens of previously unknown tribes. Yet throughout these dangerous encounters, his pacifism never wavered.

Rohter: Rondon’s policy is die if necessary. Die if you must, but never kill. And he demanded that of his expedition members, he demanded it of himself.

Possuelo: “Die, if need be, but never kill.” And this is a phrase – it's not a catch phrase that you say in your office, sitting down, smoking a cigar, drinking a whiskey and creating rhetorical sentences. It is not. It is in the heat of the battle, it's when the arrow comes to kill, he takes it off and... “Die, if need be, but never kill.”

Narrator: Cândido Rondon’s approach to Indians grew out of his earliest upbringing. Part Bororo Indian, he was born and raised in the Amazon wilderness of Mato Grosso. As a teenager, Rondon was sent to Rio de Janeiro, to Brazil’s most elite military school, where he was introduced to positivism, the philosophy that had been the guiding light of the newly formed Brazilian Republic. Its credo “Order and Progress” was emblazoned on the nation’s flag. Brazilian positivists, like Rondon, believed that social progress for Indians could only be achieved through peaceful relations and the slow introduction of modern civilization.

Possuelo: The Positivism that Rondon embraces, which is a humanistic philosophy of the brotherhood of all peoples. And Rondon had this humanistic vision that all men are equal, all men are brothers, and all have the right to experience the benefits of civilization.

TR VO: The colonel's unwearied thoughtfulness and good temper, enabled him to avoid war with indians and to secure their friendship and even their aid. Many of them are known to him personally and they are very fond of him.

Narrator: Although Roosevelt marveled at the Brazilian officer’s closeness with the Nhambiquara, and treatment of them almost as equals, it was in stark contrast with the American policy of Indian Resettlement - and Roosevelt’s own belief about the place of native people in modern society.

Rondon VO: The general impression of Mr. Roosevelt of the Nhambiquara is that they are of a much milder and gentler nature and more sociable than the great number of others. But Mr. Roosevelt said that he considers Indians wards of the Nation because they do not retain the grade of civilization which would permit them to intermingle with the rest of the population.

Jenkinson: Roosevelt didn’t dislike Indians but he didn’t think that they should be indulged in their tribal life ways. Theodore Roosevelt felt really strongly that it was the mission of the Anglo-Saxon people to civilize the world. He is a creature of his own era. He watches Rondon’s interaction with the native people and sees that maybe that’s not the American way but it works for Rondon.

Narrator: The peaceful relationship between the Nhambiquara and Colonel Rondon allowed the expedition to make its way through their land without incident. But, from here forward, Roosevelt and the team were entering unexplored land. Not even Rondon knew what to expect of the Indians they might encounter next. As they made their way past a graveyard said to hold the bodies of Brazilian telegraph workers killed by Nhambiquara, Roosevelt and his men could only wonder what lay ahead.

Whittling Down “Day 36”

Narrator: After over a month of hiking through the Amazon, the expedition had traveled nearly 350 miles. With each passing day the men drove themselves farther from civilization.

During the grueling trek almost all of their pack animals had died from exhaustion, and the Americans were forced to shed many of the provisions they had brought with them.

Even their canoes - which Roosevelt had hoped would be useful on the river - had to be scuttled.

But on February 25th, 1914, the men came to a clearing in the jungle - and, for the first time, the Americans laid their eyes on the waters of the River of Doubt.

From a makeshift wooden bridge built by Rondon’s telegraph commission, the team surveyed the surroundings.

The river appeared to be little more than a narrow mountain stream. The ink black water flowed gently northward, disappearing into a tunnel of thick jungle.

Colonel Rondon suspected that the River of Doubt was most likely a major tributary of the Madeira. If his theory proved correct, the men would paddle some 400 miles north, where they could resupply and make their way to safety in the city of Manaos.

As they prepared to disembark, it became clear that the rations the expedition was forced to shed were far more necessary than anyone had imagined. Food supplies were desperately low, and Theodore Roosevelt realized that getting down the river quickly had become a matter of life or death.

Ornig: Right from the start, Roosevelt was concerned about - will we get through, because they had discovered the bread and sugar was missing, that had been lost when they dumped cargo in the overland trip. But when you look at the canoes that were available, I think he must’ve felt internally dismay. You couldn’t help but be dismayed to look at “this is what we’ve got to go down this river.”

Narrator: Rondon procured seven hand-hewn dugouts from local Indians. In a boat fully laden with gear, Roosevelt sat just inches above the water. There was little chance that the dugouts, which weighed over twenty-five hundred pounds apiece, would be able to handle rapids as well as the North American canoes the team had left behind.

Jenkinson: I mean, if you had said to Roosevelt in New York this journey will depend upon somehow finding boats deep into the interior, and they will have been made by native people, he would not have regarded that as acceptable. And the boats are so heavily laden that they ride so low in the water that they have to take bamboo trees and lash them to the sides of the canoes to give them more buoyancy.

Narrator: With dwindling provisions and unreliable canoes, it became clear that not everyone would be able to continue on the expedition. It was decided that the American provisioner Anthony Fiala would instead be sent down a previously mapped river.

And Roosevelt’s friend, Father Zahm, the 63-year-old Catholic Priest, whose age and attitude had been a source of concern from the beginning of the journey, was also dismissed.

Jenkinson: The precipitating moment is when Zahm says he expects to be carried by natives in a sedan chair and says, “They love this sort of thing. Natives love to do this for Catholic priests. They’ll like it.” And this offends Rondon, but it just seems ludicrous to Theodore Roosevelt, and he realizes Zahm must go. And he takes him aside, and he says, “This journey as it now proceeds is done with respect to you.”

Narrator: From here, the team would consist only of Theodore and Kermit Roosevelt, George Cherrie, Colonel Rondon and his Lieutenant Lyra, and a Brazilian medical doctor. 16 off the most experienced camaradas would travel along with them.

Some of the men wrote final letters to loved ones, to be carried out by the departing team members. From here forward, they could only speculate as to when they would return to civilization.

Kermit VO: Dear Belle, Here we are ready to start down the river of doubt. No one has any idea as to where it goes. It’s almost impossible even to guess. I think we may be in Manaus in a month and a half; two months is really the most probable, tho’ three or four is possible. All I ask of the river is that it may be short, and easy to travel, and as quickly as possible. Kermit.

Down The River “Day 38”

Narrator: Just after 12 noon on February 27th, 1914, the men pushed off from shore and dipped their paddles into the River of Doubt for the very first time.

They drifted down the calm river in single file. Kermit Roosevelt paddled in the lead canoe with camaradas Joao and Simplicio. Theodore Roosevelt, with his paddlers Antonio and Julio, was in the rear.

Swollen from the unending rain, the placid water belied great dangers just beneath the surface.

Tangled vines and hidden trees threatened to capsize the bulky canoes that floated just inches above the water. And deadly piranha, anaconda, and caiman lurked within the murky depths.

But what worried the men most was the eerie silence that overcame the jungle once they were on the river – a quiet that created an uneasy sense of isolation.

TR VO: The lofty and matted forest rises like a green wall on either hand. The trees are stately and beautiful. Vines hang from them like great ropes. Now and then fragrant scents are blown to us from flowers on the banks. There are not many birds, and for the most part the forest is silent.

Rohter: It was beautiful. It’s such a gorgeous river, and it evokes something really fundamental – this closeness to nature. But it’s a kind of nature that you can’t take for granted because it’s so enormous and so overpowering. - beautiful, but threatening.

Narrator: The River of Doubt was serpentine, snaking its way through the jungle. “The stream bent and curved in every direction,” Roosevelt noted, “toward every point on the compass.”

Ornig: The River of Doubt. It was like smooth, there were no obstacles, but it had this crazy corkscrew coursing and I think they were kind of lulled into security. For the first couple days it seemed like, well, maybe this won’t be so bad. And then about the second of March, all that changed rather dramatically.

Narrator: As they rounded yet another bend in the twisty river, the expedition began to feel a dramatic shift in the current. The roar of rapids suddenly broke the silence of the jungle.

The team drove their canoes ashore to get a better look downstream. Stretching before them was a series of rapids that included at least two waterfalls.

Kermit’s hopes for a quick descent were most certainly dashed.

Jenkinson: Just a few days in they hit the first rapids. And they realize, uh-oh, this river may be much, much more difficult than we could've anticipated.

Narrator: “No canoe could ever live through such whirlpools,” George Cherrie wrote. “Only one glance at the angry water was enough for us all to realize that a long portage would have to be made.”

Possuelo: There is what they call sinkholes. So they create a whirlpool and that makes the canoe capsize, which throws everyone overboard and you could die.

Narrator: Colonel Rondon determined that the only way to continue safely down the river was to cut a path through the jungle and walk around the rapids.

The camaradas emptied the boats and dragged them up the riverbank, clearing a path as they went.

They then cut down trees to fashion rollers out of logs, employing the block and tackle method to move the hulking, waterlogged dugouts.

For two days and nights the camaradas worked tirelessly as the expedition continued to encounter rapids. Each portage cost the men precious time and rations.

Rohter: Just rapid after rapid, after waterfall, after waterfall. In the official accounts, every day they’d track how many kilometers they’ve gone from their last campsite, and at the rate they were moving, they were never going to get to the mouth of the river.

Bayard: There’s an old Roosevelt family motto, when they were out on their cross-country trips, “Over, under, through, but never around.” So we can imagine how it must have chafed at them to have to go around again and again, because these canoes were so easily smashed, so they had to protect them.

Rohter: It’s time consuming. It’s physically draining. And, worst of all, it’s demoralizing because you never know when are we going to be done with this? You think you’re finished, and then off in the distance, you hear the roar of another set of rapids. Oh, no, what’s this one going to be like?

Narrator: The extraordinary character of the River of Doubt - its power and trajectory - was like nothing Roosevelt had ever experienced in the wild.

The river squeezed its way through a canyon no wider than the length of George Cherrie’s rifle.

TR VO: It seemed, almost impossible, that so broad a river, in so short a space of time could contract its dimensions to the width of the strangled channel through which it now poured its entire volume. At one point it is less than two yards across.

Narrator: The long portages and the unpredictability of the river were wearing on the men physically and mentally.

Adding to the tension was Rondon’s insistence on making a painstaking detailed survey. Measuring every twist and turn in the river led to even more delays.

Ornig: In the first couple of days, it seemed like they could do this. Kermit Roosevelt, who was his surveying assistant, landed 114 times in one day, getting out of his canoe, crawling up onto the river bank, setting up the sighting pole while wasps and bugs and the insects are tearing him to pieces. But then when the rapids began, it became impossible. Roosevelt could not see spending so much time mapping.

Rondon VO: These developments caused a great deal of annoyance to Mr. Roosevelt who feared this should delay even more the termination of the journey. It was his earnest desire to finish in as short a period as possible, the undertaking that had brought him to these wilds. We were obliged to abandon the method previously used in the survey of fixed stations, and to adopt instead that of sighting with the front canoe in motion.

Bayard: From the start, there’s two very different objectives. Teddy Roosevelt just wants to get to the end of this river. He doesn’t care how many twists and turns it takes. He just wants to get to the end. Rondon, though, wants to measure this river and map it. He wants this expedition to be useful to the people who come after.

Diacon: Measuring, annotating, collecting, these are hallmarks of the Rondon project. It may have seemed like excruciatingly painstaking work to the Americans that was too time-intensive. To Rondon, this was business as usual - to be out there and engaged in painstaking work.

Jenkinson: Rondon wants to do this as a genuine and important scientific survey. Roosevelt wants to survive, and he feels concerned about everybody’s survival. And so there’s this building tension between them.

Simplicio “Day 54”

Narrator: After more than two weeks on the river, the expedition was making very little progress, averaging less than six miles a day. The lengthy portages around rapids, and Rondon’s mapping, had slowed them to a crawl. One night, two canoes broke loose from their moorings, halting the expedition for four days while Rondon and his men made a new boat.

Cherrie VO: Rondon would stand all day long, keeping the men working hard. The camaradas suffered greatly from attacks of insects. Their clothes were scant, their feet, hands and faces soon became sore and inflamed. But the delay would only emphasize our need to make greater speed.

Roosevelt: As time went on, particularly the Americans were getting more and more impatient. Just getting around rapids was a very arduous task if you had to portage.

Rohter: Rondon says it’s best not to try to run rapids, and we have guys here who know how to read these rapids, and let’s trust their judgment.

Narrator: On March 15th, Rondon ordered the expedition to prepare for yet another portage while he forged ahead to investigate the best way through the jungle and around the rapids. Kermit, however, tired of delays, had other plans. He ordered his boatmen Joao and Simplicio to paddle forward.

Rohter: You know, the boatmen, they were taught to obey orders from their superiors, and Kermit was one of their superiors. He’s Colonel President Roosevelt’s son, therefore he has some authority. So the two guys said, “Okay, you know, that’s what you want to do? We’re going to do it.”

Jenkinson: He instructs these two men to paddle forward. They get caught first in one whirlpool, and then in another.

Bayard: There’s no way to get back. They try to row to shore, and their boat is swept over the waterfalls.

Narrator: Kermit was dragged under, his helmet plastered to his face by the force and weight of the river. Somehow, he fought his way to the surface.

Bayard: By this time, Rondon has strolled down the landward side of the river, and he’s standing over Kermit saying, “You have had a fine bath.” But the next words out of his mouth are, “Where is Simplicio?”

Rohter: Kermit and one of the boatmen made it to the other side, but Simplicio did not. And that was a bleak moment.

Jenkinson: They look for him. He’s never recovered. They never find another trace of him. Simplicio was drowned at this enormous rapids on the River of Doubt on March 15th, 1914.

Narrator: In addition to Simplicio, the river had swallowed up over a week’s worth of rations.

Jenkinson: TR and Kermit both say that it wasn’t an act of disobedience, that the river just grabbed Kermit’s canoe, and the river took over, and there was nothing that any human being could've done about it. It was the River of Doubt grabbing the pilot boat and sweeping them downstream.

Diacon: You see a flash of anger in Rondon. “I know this world. You disobeyed my suggestion, and this is what it got us.” And it was a great disappointment and it angered Rondon.

Bayard: Kermit had disobeyed Rondon’s orders, but Kermit wasn’t one of Rondon’s men. He was a guest. He was the son of the most famous man in the world, and there was only so much Rondon could do in response to this.

Narrator: No matter who was to blame, Simplicio’s death was devastating to the men of the expedition, especially to Theodore Roosevelt.

TR VO: Grave misfortune befell us and graver misfortune was narrowly escaped. Kermit has been a great comfort to me on this trip. The fear of some fatal accident befalling him has always been a nightmare to me. He is to be married as soon as the trip is over and I cannot bear to bring bad tidings to his betrothed, to his mother.

Dalton: TR watches Kermit courting danger in exactly the way he does, and he realizes that it would be so terrible to watch your son drown right in front of you on this journey that was your journey. But he’s worrying about something that he knows very well, he’s done that all his life, and there Kermit’s doing it too.

Bayard: Kermit became, by dint of strenuous effort, the child that he thought Teddy Roosevelt wanted him to be. The kind of guy who will stand in the path of a charging elephant or lion, and coolly dispatch him with one bullet.

Jenkinson: And Roosevelt says, you know, “I worry about him - that he doesn't know when to pull back a little bit. He might push too far. He might get himself killed.”

Narrator: After the drowning, the men honored the young Brazilian’s memory, and Colonel Rondon offered a simple gravesite eulogy - here perished the poor Simplicio.

A New Danger “Day 55”

Cherrie VO: We went over our provisions today. It is estimated that we have about 600 kilometers to go. Since we started we have averaged about 7 kilometers a day. At that rate we will be shy about 35 days of food. There may be very serious times ahead.

Narrator: George Cherrie’s calculations were dire. The team had always planned to augment their rations with game from the surrounding jungle, but the Amazon was yielding very little for them to eat. The rainy season had flooded the banks, forcing game deep into the forest, and the men had little success catching fish in the swollen, muddy river.

Bayard: They’re running out of food, and that has to be an astonishment for noted game hunters like the Roosevelts. They went across Africa, they bagged more than 500 mammals over the course of their travels. Here they are in this incredibly abundant biosphere, and they can’t find food. So, it’s starting to prey on their bodies, it’s starting to prey on their minds.

Narrator: Adding to their sense of despair was the feeling that they were being watched. The men spotted evidence of Indians along the shore, smoldering fires from abandoned campsites, fish traps, and trail markings.

Possuelo: Aside from all the dangers they were subjected to by the topography, by the lack of knowledge of all that was going on, this course that Rondon is making on the River of Doubt is an unknown one and is inhabited by tribes and these tribes attack.

Narrator: Determined to find food for the expedition, Colonel Rondon ventured deep into the jungle to hunt. After just a few hundred yards, he heard the yelps of what he thought was a spider monkey and then the sound of human voices. He scrambled through the brush to discover his hunting dog Lobo had been killed.

Jenkinson: He hears the yelps and finds that it’s been shot through. Long arrows. And he realized that the dog has been killed by native peoples.

Rohter: Even Rondon has no idea who they are. They’re in truly unmapped territory, not just in the literal sense, but: who lives here? We don’t even know. We’re being watched, and we don’t know who is watching us.

Gomes: The Cinta Largas, the Suruí and the Zoró Indians who lived around that area probably didn’t have any idea who Rondon was. The Cinta Largas were famous for attacking other people. It was known that they didn’t want to have relations with Brazilians, in general, with anyone, so they had a propensity to attack whoever would come into their territory. I remember talking to the Cinta Largas once and they said, “Yeah, our ancestors talk about a trip of some guys on dugout canoes and watching them and not knowing what to do with them and whether to attack them or whether to let them go.”

Roosevelt: The Indians could have been completely invisible if they wanted to. But they didn’t. They wanted the expedition to know that they were being watched. They shot the dog dead. This is the first indication of deadly force.

Narrator: Confident that the murder of his dog was merely a warning, Rondon responded peacefully, leaving gifts for the unknown tribe. But the Americans were growing concerned that this was the beginning of an all-out assault.

Diacon: If I were amongst the U.S. delegation, that’s how I would have interpreted it. It would have worried me, and I know it worried the Americans.

Dalton: Theodore Roosevelt assumed that Rondon knew this area and had some sense of control, or knew what was predictable on one of these journeys. And now, Theodore Roosevelt realized that he was on an unknown river with an explorer who may be was outside of his depths. He’s not sure what’s happening next.

Narrator: Around the campfire, the men could hear voices breaking through the hum of nighttime insects.

Carlos Fausto, Anthropologist: Hearing these sounds during the night, this is really scary. Really, really scary. You can’t tell the difference between your place and the forest. And you know that that’s not your place.

Narrator: The expedition kept their rifles at the ready, but the Indians remained hidden.

Roosevelt: They were sleeping at night, knowing they’re there. And knowing in the middle of the night, one of them could come in and slit your throat and then creep out again, and nobody would know, until the next morning.

Narrator: With the specter of violent Indians lurking on the shore, Roosevelt lost all patience with Rondon’s continued delays.

Ornig: Roosevelt said we’ve got to stop this very careful mapping. The two colonels had a big, big argument in the tent - that he didn’t want his son to be out in front anymore. “And you must adopt this, uh, another method of surveying. I will not have my son put in mortal danger for a map.”

Rondon VO: Roosevelt said to me, “Great men don't bother with details.” And I responded that, “I'm not a great man and this is not about details. This survey is something imperative, without which this whole expedition would be pointless.”

Jenkinson: Rondon then said, “I’ll tell you what, I’ll, we’ll move ahead faster, I’ll escort you out. I’ll accommodate your needs, and I’ll move quickly so I can escort you off the river.” Rondon is essentially now saying, “You’re reverting to a celebrity. You’re not really an explorer because you’re really thinking more about getting out, than you are about the actual, really difficult work that it would take to do this right.”

Fausto: It was hard for Roosevelt because he was not in control. Roosevelt was playing the following game: I will make Rondon believe that he is in charge, but I am the man. But in a certain point, he discovers that Rondon was doing the same, and much more effectively, because he was the only one who could take them out of the situation.

A River Renamed

Narrator: On the morning of March 18th, 1914, Colonel Rondon gathered the men of the expedition to make an official announcement.

He had determined that the River of Doubt was a major Amazonian tributary now deserving of a proper name.

The River of Doubt, he proclaimed, would now be known as the Rio Roosevelt.

Rohter: This is a moment of achievement. This river is a majestic river, it’s a major river. It’s a moment that establishes the nominal purpose for which Teddy has come.

Narrator: Getting to this point on the river hadn’t been easy on the Americans. George Cherrie wrote that Roosevelt was looking “so thin that his clothes hang on him like bags.” And no one had any idea when it would end.

But Rondon’s gesture of naming the river after the former president momentarily buoyed the men’s spirits.

Ornig: There was three cheers for Kermit, three cheers for Colonel and then someone said, “We’ve forgotten Cherrie. Three cheers for Cherrie!” Cherrie says, “It took so little to cheer us, any bit of good news, when you reach a point of despair like that, the littlest thing can give you hope.”

Lost

Narrator: On March 23rd, 1914, Theodore Roosevelt’s wife Edith awoke to alarming news. The New York Times was reporting that her husband and son were lost on an unknown river in the Brazilian wilderness.

Bayard: When word arrived that the expedition had been lost, Edith was worried that Teddy met more than his match in the jungle.

Narrator: The last correspondence Edith had received from Theodore was on Christmas Eve, when he was making his way into the Brazilian backcountry. His only complaint was the constant “prickly heat.”

Ornig: She had no way of knowing what was happening. Well, she’d been used to being, you know, worried dreadfully about his escapades - when he went into the Spanish War, when he left for Africa.

Narrator: The worrisome news in The Times came from a desperate telegram sent by American provisioner Anthony Fiala. The message described his own harrowing journey out of the jungle, after he was dismissed from the expedition.

Jenkinson: Fiala didn’t clarify that the expedition had split, that he was part of one of the secondary strains. The New York Times reckoned that that meant the whole expedition had miscarried.

Narrator: For Edith Roosevelt the news was hard to believe.

Dalton: For her entire marriage, she knew that TR was facing danger often. When he was in Africa, it was reported that he was killed, and she read that and, you know, it was upsetting to her, but there was a part of her that didn’t believe it. So she was not going to go into mourning because this was a guy who had been reported dead several times. And so, this trip, she sent Kermit as life insurance. She has set Kermit up to be the person who is going to rescue Theodore Roosevelt from himself. She just had to believe that she was going to see them again.

Narrator: The very evening of The New York Times story, George Cherrie had made a desperate entry into his diary.

“Our position,” he wrote, “every day grows more serious.”

The naturalist estimated that half the provisions were already gone. With likely hundreds of miles yet to go, the men had food for just 25 more days.

And the expedition was still mired in rapids that required endless portages through the jungle.

TR VO: No one can tell how many times the task will have to be repeated, or when it will end, or whether the food will hold out; all this is done in an uninhabited wilderness, or else a wilderness tenanted only by unfriendly savages, where failure to get through means death by

disease and starvation. Every hour of work in the rapids is fraught with the possibility of the gravest disaster.

Narrator: On March 27th, two of their dugout canoes were pulled under by the ferocious current and became lodged between slick rocks.

Weakened by hunger, illness, and weeks of backbreaking portages, Roosevelt, Kermit, and several camaradas struggled for hours to dislodge them.

The men eventually freed their canoes but not before Roosevelt slipped in the churning water and gashed his shin.

Jenkinson: Blood starts to swirl out. And everyone realizes, this is a whole new chapter in this story now.

Bayard: In the jungle, the slightest contusion, abrasion, is going to magnify and metastasize and grow, so very soon this is a full-boiled infection that’s slowly colonizing his leg, and is spreading poison into his system.

Narrator: Roosevelt assured his team that the wound was little more than a scratch. But at camp later that night, he spiked a dangerously high fever.

An Obstacle They Could Not Pass “Day 67”

Narrator: On the morning of March 28th, despite his weakened condition, Theodore Roosevelt took his place alongside the other men, and continued down the river.

But the expedition traveled less than a mile before they were forced to prepare for another portage around rough water.

As they cut a path through the jungle, the men came upon a clearing and, for the first time since setting off on the river, they could see what lay ahead. Below them stretched a canyon, over a mile wide.

Cherrie VO: It was a beautiful view but it filled everyone with dread. We had learned that whenever the river entered among the hills that it meant rapids and cataracts and our strength and courage alike were almost exhausted.

Narrator: The men had finally met an obstacle around which they could not portage.

Ornig: This group of men were faced with continual series of dilemmas. When they reached this canyon, Rondon wants to dump the canoes and march overland and then build new ones on the other side, which the Americans thought was crazy. If they had left the dugouts behind, they would have to spend days, if not a week, rebuilding canoes and then they’d be subject to perhaps another attack.

Narrator: “To all of us,” Cherrie wrote, “this news was practically a death sentence.”

It was a wonder that Theodore Roosevelt had made it this far.

He had arrived in Brazil grossly overweight, practically blind in one eye, and with a heart weakened from his childhood asthma.

Now, wracked with a fever made worse by the onset of malaria, and a festering leg infection, Rondon’s plan to hike around the gorge was simply not an option for the battered ex-president.

That night, Cherrie and Kermit kept watch over Roosevelt. Kermit, through all their travels together, had never seen his father so defeated.

Jenkinson: Roosevelt calls in Kermit and Cherrie. And says, “Boys, this is it. Either we all die, or I die and you all get out, and obviously there’s no choice. You have to, you have to leave me here.” Because he realizes that his decrepit condition may jeopardize the survival of everybody else.

Narrator: For years, whenever on an adventure, Roosevelt had secretly carried a vial of morphine. It was, he later admitted, to avoid dying a lingering death.

Jenkinson: Theodore Roosevelt has been to war, broken many bones in his body. He’s always getting battered and beaten and broken. He’s indomitable. So imagine what it would take for Theodore Roosevelt to say, “I have to die”. But Kermit says, “No, that’s not going to happen. We’re going to get you out of here.”

Narrator: Kermit quickly devised a plan to lower the canoes through the gorge, rather than abandon them.

Roosevelt: The gorge is a pretty dramatic gorge with high walls on either side, and the river roaring through it.

Ornig: The workers had this natural ability. They knew how to handle these boats.

Narrator: Kermit designed a pulley system that the camaradas used to lower the empty canoes over a series of waterfalls, some as high as 30 feet.

Ornig: They had to get these boats let down walking on ledges. They barely had a toe-hold. They were like insects pressed against the wall of this chasm.

Roosevelt: Imagine hanging on to something, the thing weighs 2,000 pounds. How easily it could be whipped away and drag you with it.

Narrator: After four exhausting days descending several sets of violent rapids and steep waterfalls, the men finally reached the northern end of the canyon. Somehow, through it all, they lost only one canoe.

Rohter: It’s a moment of enormous stress and potential danger. And Kermit is clear thinking and rigs a solution. It’s kind of like the moment where Kermit earns his bones.

Narrator: Bolstered by the success of Kermit’s plan, Theodore Roosevelt summoned the strength to carry on. Though too weak to walk more than a few hundred yards at a time, Roosevelt eventually limped his way out of the canyon.

Jenkinson: Roosevelt himself realizes that he no longer has everything it takes to be the inevitable commander, but his son has those qualities, and his son’s youth, and strength, and will might just get them through.

A Murder In the Ranks “Day 73”

Kermit VO: There is a universal saying, “When men are off in the wilds they show themselves as they really are.” Without the minor comforts of life he is not always attractive. He may seem a very different individual when on half rations, eaten cold and sleeping from utter exhaustion, cramped and wet.

Narrator: After a month of paddling on the River of Doubt, the men were weak from hunger and disease and still had no idea where the river would lead them next - or when the journey would come to an end.

Jenkinson: They didn’t know what was around the next bend in the river. They didn’t know long the river was, whether it was 7 kilometers or 700. They didn’t know how many days it would take. So the mystery of it begins to gnaw at them.

TR VO: We have lost four canoes and the life of one man, we have not made more than a mile and a quarter a day at the cost of bitter toil, most of the camaradas are downhearted naturally enough, and occasionally ask one of us if we really believe we will ever get out alive. We have to cheer them up as best we can.

Bayard: You see in the accounts as the journey goes on, an increasing sense of despair. And as it continued to wind and ribbon and turn, it’s starting to prey on their bodies, it’s starting to prey on their minds, and they’re not the same people that began that journey.

Narrator: On April 3rd, 1914, as the expedition set up its 30th camp along the riverbank, a burst of gunfire broke the silence of the jungle.

Two of the camaradas, Julio and Paishon, had been arguing after Julio had been caught stealing food.

Ornig: Julio was sort of a malcontent and shirker of work, and he liked to steal food, and I guess as things got worse, he got extremely hungry. And something snapped in Julio and he noticed a rifle nearby, and at an opportune moment, killed Paishon.

Narrator: By the time the men reached Paishon, he was dead - shot point blank in the chest.

Bayard: They’re running out of food, they’re running out of time, and that changes their calculus of what’s right and wrong. I don’t think that’s a crime that could have happened at the beginning of the trip. It’s no surprise that he snapped. You have a group of men who just aren’t convinced they’re going to survive this. Teddy Roosevelt, he must have thought, “If they’ve started killing each other, what will happen next, and who will be left at the end?” It’s a Darwinian equation, you know? The fittest are going to survive, and they won’t necessarily be looking out for each other at the end. So they’ll inevitably start turning on each other.

Narrator: Julio disappeared into the jungle. It was possible he’d be swallowed whole by the unforgiving wilderness, killed by Indians, or continue to stalk the expedition - nobody knew for sure.

TR VO: On such an expedition the theft of food comes next to murder as a crime, and should by rights be punished as such. Franca, the cook, expressed with deep conviction a weird ghostly belief I had never encountered before. He said, “Paishon fell forward on his hands and knees, and when a murdered man falls like that his ghost will follow the slayer as long as the slayer lives. Paishon is following Julio now, and will follow him until he dies.”

Roosevelt: There was a murderer in the woods so now the question is what to do? Try to track him down or not track him down.

Diacon: Rondon wanted to essentially take this murderer as a prisoner and take them with them and then subject him to military judgment, and Roosevelt was like, “No way. That’s just one more mouth to feed. Let’s get going.”

Narrator: Rondon insisted that they continue the manhunt. For Roosevelt, who was plagued by fevers and a deepening abscess on his leg, further delay was unthinkable.

Bayard: Rondon is still slowing things down in a way that Roosevelt must find increasingly intolerable. It must have been excruciating that they would stop at this point and go search for this man. They should be heading onward. Again, it’s that tension. And that tension is approaching the breaking point at this point.

Ornig: The two colonels continued to argue. They would quarrel, but they they couldn’t get to the point of having a break like, “Well, I’m going this way, you can go that way.”

Narrator: As the men continued downstream, Julio, to their surprise, reappeared along the river bank, pleading for his life.

But Roosevelt and Rondon were in agreement. They decided to let the jungle determine his fate.

Rohter: And Rondon goes right by him, as does the canoe with Roosevelt.

Ornig: And they all pass by in stony silence.

The Coleridge Haze “Day 74”

Narrator: It had been two and a half months since the men set out into the wilderness. They had traveled nearly 600 miles - 375 over land and more than 200 on the river. With the mountainous terrain of the canyons behind them, the men hoped for a smoother descent to the mouth of the River of Doubt.

But on the night of April 4th, Roosevelt’s malarial fever returned with a vengeance. With few medications at his disposal, the expedition’s doctor injected quinine directly into the former president’s stomach.

Kermit, Cherrie, and Colonel Rondon took turns sitting by Roosevelt’s sickbed.

Kermit VO: The scene is vivid before me. For a few moments the stars would be shining, and then the sky would cloud over and the rain would fall in torrents shutting out sky and trees and river. Father first began with poetry; over and over again he repeated “In Xanadu did Kubla Khan a stately pleasure dome decree.”

TR VO: In Xanadu did Kubla Khan a stately pleasure-dome decree…

Roosevelt: There was a point where nobody really thought he was going to live through the night, and he was raving.

TR VO: In Xanadu did Kubla Khan a stately pleasure-dome decree…

Dalton: Theodore Roosevelt’s fevers come back, and he becomes delirious. He’s not really himself.

TR VO: In Xanadu did Kubla Khan a stately pleasure-dome decree…

Jenkinson: Here in the middle of this dense tropical jungle, TR starts to recite from Kubla Khan. In Xanadu did Kubla Khan a stately pleasure-dome decree: where Alph, the sacred river, ran through caverns measureless to man down to a sunless sea. It’s a magnificent, haunting, romantic poem and fitting for this moment. They are in chasms measureless to man trying to get to the sea.

TR VO: In Xanadu did Kubla Khan a stately pleasure-dome decree…

Bayard: A simple line is repeated again and again and again. He’s still aspiring to the summer palace of Kubla Khan, to the great heights of the pleasure dome. He’s still reaching out, reaching up. He’s not cowering in the face of death.

TR VO: In Xanadu did Kubla Khan a stately pleasure-dome decree…

Narrator: Drifting in and out of delirium, Roosevelt told Rondon that the expedition must proceed without him. They could not afford further delay.

Rondon VO: He was with fever and delirious. I said the expedition can not carry on without you. It is impossible. This expedition is called Roosevelt-Rondon! That was my argument to his plea.

Possuelo: Rondon responds accordingly. “Never.” Rondon tells him, “No. We’ll all come out of this together or we’ll all die together, but I'll never abandon you. Do not even think of this.”

Ornig: Rondon said, “But you are the expedition.” Rondon could not see leaving him behind. That was unthinkable. The admiration had still survived all the contention, all the hardship.

Rohter: In a military expedition you don’t leave your guys behind. It was a non-starter - Roosevelt’s delirious request.

Narrator: From here forward, the ex-president would have to rely on the other men to carry him out of the jungle.

The expedition continued down the river, with Roosevelt now lying beneath a makeshift canopy.

Kermit VO: Down beyond the rapids the river widened so that instead of seeing the sun through the canyon of the trees for but a few hours, it hung above us like a molten ball and broiled us. To a sick man, it must have been intolerable.

Narrator: When Roosevelt set out on the River of Doubt expedition, he famously wrote a skeptical friend that he had already lived and enjoyed as much life as any nine other men and was quite ready to leave his bones in South America.

But on April 15th, 1914, it suddenly became clear that Theodore Roosevelt was going to live to tell the tale of yet another great adventure.

Jenkinson: They see a marking that says “J.A.” And so they know it’s somebody with an alphabet.

Narrator: It was the first trace of the outside world that the men had seen since launching their dugouts a month and a half earlier. It was a clear indication that salvation lay ahead.

After a few more hours on the river, the men spotted smoke billowing out of a thatched-roof home. The expedition had reached a tiny outpost of rubber tappers.

Diacon: I think that’s the moment that everybody realized they were going to, they were going to live.

Cherrie VO: Shouts of exaltation went up from our canoes as this frail outpost of civilization met our eyes. What a delightful sight it was. Uncertainty was at once a thing of the past. Finally, we had reached a point below which the river was known.

Jenkinson: After all of this uncertainty, they realize we will complete the journey. And so here’s the President of the United States, the former President and one of the world’s great men, just prone in the boat unable really to even sit up at this point.

Narrator: The ordeal had left the men gaunt and wild eyed from hunger. Their clothes were in tatters, their skin burnt and covered in insect bites, and Theodore Roosevelt was barely clinging to life.

None of them could believe that they had made it to civilization.

On April 26th, after paddling more than 400 miles, the men had finally covered the length of the River of Doubt. At the mouth of the river a rescue boat from the Brazilian navy was waiting to ferry them to the city of Manaus.

The river had claimed the lives of three of the expedition’s men, swallowed almost all of their possessions, and nearly killed Theodore Roosevelt.

Along the way, friendships and family bonds had been put to the test. But somehow they withstood and, in some cases, were even strengthened by the experience.

Jenkinson: When they finally come out, Rondon stops the little steamer that they’re on at 2 a.m., in the middle of the night, so that Roosevelt can quietly be taken off of this boat on a stretcher and not be seen as an invalid. Rondon wants to protect his dignity. Not have TR be seen as a man who’s become incapacitated by this journey.

Narrator: From Manaus, Roosevelt sent a telegram to his wife Edith after months of silence. “Successful trip,” he wrote, and gave no hint of his condition.

Cândido Rondon did not waste time on goodbyes. As soon as the Americans set sail, Rondon turned around and returned to the jungle.

He threw himself into the last crucial stages of his telegraph project and resumed his work for the protection of Indians.

Rohter: Roosevelt says to him, “You should go home to your family,” and Rondon says, “I’d like to, but I have this task I have to finish,” and so he just goes right back into the jungle. After this grueling, grueling experience Rondon continues on his life’s work. It’s remarkable.

Narrator: Roosevelt quietly returned to New York, slipping off the boat at Oyster Bay near his home in Long Island.

When reporters caught up to him, they were shocked by how he looked. The President was gaunt, he had lost more than fifty pounds in the Amazon, and, for the first time in his life, he was leaning on a cane.

Despite his weakened condition, Roosevelt was in a fighting mood. Many of the most distinguished members of the American and British geographical societies were challenging his claim that he had charted a major South American river. Some saw his trip as nothing more than a publicity stunt to launch another bid for the presidency.

Jenkinson: It just throws him into a kind of a Rooseveltian righteous rage. To think, “I nearly died. This was an absolutely perilous mission, and to be doubted by people who have never been to South America.” So he goes to the National Geographic Society, and he proves to them that he did it.

Ornig: He had photographs, he even drew a map. Roosevelt talks about, “We spent 60 days, there was no way we could have got there except by the river in that time. So, therefore, accept the fact that there’s a river of that length there that you’re not aware of.”

Narrator: Two weeks later, Roosevelt was redeemed before an audience at the prestigious Royal Geographical Society in London.

Jenkinson: When he walks in, he gets this gigantic ovation, and he realizes they love me. I’m a hero. Then the National Geographic Society gives him a medal, and he says in his acceptance speech, “it needs to go to Rondon,” and so they strike a second one, which goes to Cândido Rondon because Roosevelt refuses to be the sole person to take credit for this extraordinary mission.

Narrator: Roosevelt had fulfilled his dream of becoming a famous explorer, his name etched forever on the map of South America. But nature had exacted a heavy price. Roosevelt’s sister Corrine would later say, “The Brazilian wilderness stole away ten years of his life.”

He never fully recovered his prior vigor, and was plagued by recurring malaria.

Theodore Roosevelt died on January 6th, 1919, just five years after the returning from the Amazon.

Kermit Roosevelt, who returned from the expedition to finally marry his great love Belle Willard, was devastated at the news of his father’s death.

“The bottom has dropped out of my life,” he wrote to his mother. Without his beloved father, Kermit lost his mooring, and after battling alcoholism for most of his life, committed suicide in 1943.

Cândido Rondon spent the rest of his life fighting for the rights of Brazil’s indigenous people and lived to be ninety-two years old. Today, the state of Rondonia bears his name.

Possuelo: Rondon is one of the biggest heroes of this country. I say that heroes are the ones who give to humanity, who transform humanity for the better and leave examples of ethics, of justice, of work, those are the greatest heroes of life. So that's how I see Rondon, as one of the greatest heroes of Brazil.

Narrator: In life and in death, Roosevelt and Rondon both became heroes. But the journey they shared down the river that now bears Roosevelt’s name has a legacy all of its own.

Bayard: The story of the Roosevelt-Rondon expedition is both inspiring and deeply cautionary. It shows that human enterprise has its limits. There is no more formidable example of willpower than Teddy Roosevelt, but he didn’t tame that jungle, he didn’t domesticate it, he just survived it. And even he, at the end, had to acknowledge his limitations. And as soon as they left, the jungle folded round and eliminated every last trace that they had been there.