Deputy Director, CIA (archival audio): This is a result of the photography taken Sunday, sir. There's a medium-range ballistic missile launch site and two new military encampments.

John F. Kennedy (archival audio): How far advanced is this?

CIA Analyst (archival): Sir, we've never seen this kind of installation before.

Narrator: Only a few people knew of the existence of the surveillance photographs, much less the terrifying revelations they held.

In October 1962 the Soviet Union was constructing nuclear launch sites in Cuba, within range of every major city on the Eastern seaboard -- including the U.S. Capitol.

Evan Thomas, Writer: It's hard to realize how frightened they were. They had conversations about evacuating great parts of the United States. They had estimates about how many tens of millions of people would die. They really thought that war was near.

Narrator: Managing this crisis fell to a rookie president: John F. Kennedy. He was less than two years on the job, the youngest man ever elected to the office.

Thomas Hughes, Aide to Sen. Hubert Humphery: Nothing prepared him for this. The things that got him elected -- the acute politician, the charming vote getter, the-the money, the glamour -- none of it had any bearing at all on his situation.

Narrator: The qualities that had carried John Kennedy to the presidency -- natural rebelliousness, stubborn self-reliance, spectacular self-confidence -- had also led him to make mistakes and missteps that helped put the country in mortal danger. His predecessor in the White House, Dwight Eisenhower, had called him "Little Boy Blue" and thought his wealthy father had bought him the office. The Soviet Premier, Nikita Khrushchev, had taken Kennedy's measure at their first meeting a year earlier and he walked away believing he could get the better of the untested president.

If John F. Kennedy doubted himself, or quailed at the enormity of the situation, he didn't show it.

Evan Thomas, Writer: He had a very great ability to step back, to be cool, to be detached, to not get sucked in by the passions of the moment, to not just ride the wave.

Michael Dobbs, Writer: When he became angry, he tended to become very calm. There was a kind of burning anger in him that he didn't express very openly.

Timothy Naftali, Historian: This man was fiercely independent, intellectually independent. Fiercely. Kennedy had an unshakable sense of his own skills. He was confident about his ability to come up with the right answer.

He wasn't bringing people together in a room to hammer out a consensus. He was bringing people in a room to give him the best information so that he could make the decision.

Sally Bedell-Smith, Writer: He had what he called the "great man" theory of governing. As a consequence, it put a lot of pressure on him.

Narrator: Now, at a moment of peril and uncertainty, he would be forced to answer the question that had dogged him his entire career: Was he as tough, as smart, as capable as he appeared?

John F. Kennedy (archival): Good evening my fellow citizens. Within the past week unmistakable evidence has established the fact that a series of offensive...

John F. Kennedy (archival audio): Mrs. Lincoln... 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10... I was the descendent of three generations on both sides of my family of men who had followed the political profession. In my early life, comma, the conversation was nearly always about politics. Period.

Narrator: By the time he came of age, John Fitzgerald Kennedy inhabited a world of special exemption: the family estate in suburban New York, the summer compound in Hyannis Port, the winter retreat in Palm Beach. The story of his family's heroic multi-generational rise from the want of Irish famine might well have been a misty old folktale. The past was not the point in the Kennedy household.

Jack's father, Joseph P. Kennedy, was one of the wealthiest men in America: an Irish-Catholic businessman who had grabbed his fortune in the WASP-dominated world of high finance, and then became a celebrated administrator in President Franklin Roosevelt's momentous New Deal government. Joe Kennedy expected his sons in particular to have a large effect on the world.

Robert Dallek, Historian: He's a model of what they're taught to emulate. He's striving. He's reaching. He's always on the move. He's accomplishing. And it was expected of them to do the same thing.

Evan Thomas, Writer: They were very pampered and enabled. They were made to feel special, which is good, and they were special, and they were made to feel obliged to serve their country; that was great. But they were also given a kind of confidence that it would always go well for them.

Robert Dallek, Historian: After the stock market crash occurred in 1929 John Kennedy didn't know that there was all this privation in the country. He never wanted for a meal. And it wasn't until he read something later in high school and college about the Depression that it registered on his consciousness.

Narrator: Even in the raucous Kennedy clan -- even among his eight brothers and sisters -- Jack stood out. He kept his own schedule -- usually late. He was apt to test the patience of his elders, unconcerned with rules, and loose with money. He plied shopkeepers with the promise that his father would pay the bill, whatever it was.

Robert Dallek, Historian: Jack would expect maids to take care of him, cook his meals, do his laundry, pick up his clothes. And so he has a very privileged childhood, except for one thing: that he is burdened by a series of considerable health problems.

Narrator: Jack almost died of scarlet fever in 1920, just before his third birthday. Two years later, a case of whooping cough landed him in another quarantine ward. Soon after his parents shipped him off to a prestigious boarding school in Connecticut, Jack's letters home began to include reports of his shaky health. At Choate, Jack's ongoing digestive ailments made him a reliable customer of the campus infirmary.

David Nasaw, Historian: Jack didn't know what was wrong with him. All he knew was that on a regular basis he would take sick, get a high fever, end up in the hospital, that he couldn't gain weight, that he couldn't run around and play sports the way he wanted to.

Robert Caro, Historian: He was terribly thin. He had recurrent bouts of nausea and vomiting, continual bouts of high fever, and he was tired all the time.

Robert Dallek, Historian: Joe Sr. worried that Jack might take on the image of someone who lacked the physical strength to achieve great things in life. By the time he was 17 years old, his health was so questionable, they sent him off to the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, to try and figure out what his problems were.

Narrator: Test results at Mayo indicated that Jack suffered from an intestinal inflammation called colitis. But the doctors warned him that he might have hepatitis, or worse, leukemia. When his blood count dropped to near-fatal readings, he made light: "they call me '2000 to go Kennedy,'" he wrote a friend, "took a peek at my chart yesterday and could see that they were mentally measuring me for a coffin."

Robert Caro, Historian: He never stops joking and laughing, even in the worst circumstances. When the wife of his headmaster at Choate comes to visit him she says, "Jack never stopped kidding around with me the whole time I was there."

Sally Bedell-Smith, Writer: He had to become very stoic, and at the same time he had to project an image of vitality. So although he was feeling poorly a lot of the time, he couldn't let on that he was feeling poorly.

Narrator: Joe Sr. refused to lower expectations for his second son, whatever his illness. "Don't let me lose confidence in you again," Joe wrote to Jack after a less-than-sterling report from the headmaster at Choate, "because it will be… nearly an impossible task to restore it."

Robert Dallek, Historian: Joe Kennedy, Sr., drives this point home to his sons. Joe Kennedy's message to them is: Second is never good enough. Only first. Only winning. Only being at the top.

Evan Thomas, Writer: Joe Jr. was picked out: "You're going to be President," and Joe was determined to please Dad, and was going to do whatever Dad wanted. He was a familiar type: student body president, captain of teams, best-looking boy, destined for success.

Jack was one step away. Yes, he wanted to please Dad, but he might think about it for a second. And there stirred in him a little quiet, and maybe even more than quiet, rebellion.

David Nasaw, Historian: The problem with Jack, at least for his father, is he doesn't take anything seriously. Nothing.

At Choate, where there is a strict prep school behavioral code, where the last thing you do is snicker or make fun of your teachers or talk behind their backs, Jack just can't help himself. The more pompous the headmaster, the more ridiculous the speeches at chapel, the more he feels absolutely compelled not only to make fun himself but to draw his circle of friends in. When he organizes a prank, all the other boys are in.

Narrator: Jack Kennedy was a capable student in the courses he liked, indifferent to those he didn't. His acquaintance with the rules of spelling and grammar appeared fleeting. He spent much of his depleted energy on campus high-jinks... or romance. Even in high school, his roster of conquest was a source of wonderment. "It can't be my good looks," he wrote to a Choate friend, "because I'm not much handsomer than anybody else. It must be my personality."

When Jack announced his decision to join his prep-school friends at Princeton instead of following Joe Jr. to Harvard, his father made his disappointment known: "You want to get away from your brother, I take it. Too much competition."

Fall term 1936, Jack enrolled at Harvard.

Evan Thomas, Writer: The Kennedys were a loving family but bitterly competitive. This comes from the father, but it becomes entrenched in them. They were always putting each other down -- verbally, games, sailing, touch football -- nonstop competition. And a lot of it's joyous but there's an edge there too, almost a meanness.

Narrator: Where Joe Jr. and Jack were concerned, friends remembered, "everything was a contest, whether a swim in the pool or a race to the breakfast table."

David Nasaw, Historian: Jack was always smaller, punier. He never gave up, and he always got beat up. It was par for the course.

Robert Dallek, Historian: Jack would indulge in these sort of hit-and-run attacks. And it would frustrate Joe Jr., who would dash after him. But Jack was fast, and Joe wouldn't necessarily catch him. And so Jack learned how to compete in an effective way, in a world where he wasn't always the biggest, the strongest, the smartest.

John F. Kennedy (archival): Bye, Rosie.

Rose Kennedy (archival): Bye Jack.

Narrator: At the end of Jack's sophomore year at Harvard, Joe Kennedy took a new job in London as ambassador to America's most important ally. Jack trailed his father across the Atlantic a few months later for a summer's work in his father's new office.

Robert Dallek, Historian: When Joe Kennedy, Sr., became ambassador to Great Britain in 1938, it opened up a world for Jack which he had not quite glimpsed before. There was his father at the center of British social life, and it allowed Jack to make intellectual as well as social contacts with the most important people in Great Britain, and to engage in conversation and intellectual exchange, which stimulated him greatly. These were the roots of his interest in international affairs.

Narrator: Jack had a front row seat that summer, in the most consequential season of international gamesmanship in a generation. The German leader, Adolf Hitler, had spent the previous five years building the most powerful military Europe had ever seen, and in 1938, he was showing signs he might use it. Hitler had already frightened Austria into accepting annexation and he was menacing Czechoslovakia and Poland. The rest of Europe -- and America too -- was trying to figure out how to handle the German threat.

Joe Sr. knew what was at stake for his country, and for himself. There was talk among serious Democrats that Joe Kennedy was in line for the Presidency... if Franklin Roosevelt decided not to run in 1940.

The Ambassador never stopped talking politics and policy, even when the workday was over, at the family's temporary residence, 14 Princes Gate, Westminster, London.

Sally Bedell-Smith, Writer: Joe Sr. loved to encourage spirited debate among his children, particularly at mealtime. One of his friends said that she liked to watch what happened at the dinner table. It was sort of like Joe would drop a depth charge and wait for something to explode.

Jean Kennedy Smith, Sister: There was a lot of conversation about France and England, and what was going to happen with England, what would happen with America, and would we enter the war.

David Nasaw, Historian: Joseph P. Kennedy was convinced that if the United States was drawn into a war in Europe that it would ruin the economy. Democracy would be lost. The millions of dollars he had put aside for his boys would be lost, the America he knew and loved would be lost, and it wasn't worth it. Europe was Europe. It was an ocean away. And he figured anything was better than going to war with Hitler. So why not try to make a deal with Hitler.

Jack Kennedy listened to his father. And he sat and argued with his father at the dinner table about economics and world affairs.

Narrator: Jack was back at Harvard in the fall of 1938. He monitored from afar the international summit in Munich, where British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain struck a deal to cede a small piece of Czechoslovakia to Germany in exchange for a promise from Hitler that he would stop there. He also saw his father congratulating Chamberlain for keeping the peace.

Joe Kennedy, Sr. (archival audio): When asked by the newspapermen this afternoon what I thought the chances were of appeasement succeeding, I told them I wasn't sure at all, but it was certainly worthwhile trying.

Narrator: Jack asked permission to spend the next semester back in Europe, so he could gather material for a senior thesis. U.S. embassies and consulates would be obliged to welcome Joe Kennedy's boy. He was back at his parent's home in London by March 1939, right around the time Hitler broke his promise to Chamberlain and seized the rest of Czechoslovakia. Jack headed straight for the Continent, and beyond, to see for himself what was happening.

David Nasaw, Historian: He questions people. He talks. He listens. He reads the headlines. He hangs out in the consulates. He tries to talk to the diplomats in each of these countries, and to the newsmen, the journalists.

Narrator: Jack got as near the action as he could get -- the border between Germany and Poland -- where Hitler's powerful war machine appeared to be massing for attack.

He was safely back at his father's embassy in London on September 1st, when German soldiers crossed into Poland, and German planes began bombing cities, killing innocent civilians. Britain was bound by treaty to defend its ally, Poland, and Jack was at the House of Commons to hear the war talk. He was on the streets, watching, as England prepared for war and he listened in on Prime Minister Chamberlain's address to a nervous nation.

Neville Chamberlain, Prime Minister (archival audio): You can imagine, what a bitter blow it is to me, that all my long struggle to win peace has failed. Yet I cannot believe that there is anything more or anything different that I could have done ...

Narrator: Chamberlain's weakness -- his dispirited call to arms -- was something Jack Kennedy would never forget.

The onset of war did offer Jack his first shot at public service and at public attention. When a German U-boat sank a British passenger liner with more than 300 Americans on board, Ambassador Kennedy sent 22-year-old Jack to reassure the survivors that the Embassy would get them safely home. "Mr. Kennedy," wrote a British newspaperman, "displayed a wisdom and sympathy of a man twice his years."

He arrived for his final year at Harvard with a self-confidence that surprised his professors, and a new sense of purpose. He spent his last semester grinding away at his honors thesis, "Appeasement at Munich." Jack's thesis cut against prevailing public sentiment, which held that British Prime Minister Chamberlain's actions at Munich had been dishonorable -- even cowardly. Chamberlain's appeasement of Hitler, he argued, had been understandable. Britain had been so lax in building its military in the previous decade that the Prime Minister had little choice but to go to the negotiating table and buy time.

The 150-page paper got mixed reviews. His professors found it "wordy," and "repetitious." But they had to admit it was an intelligent discussion of complacency in pre-war Britain. Joe Sr. was impressed enough to help get the thesis published. By the time John Kennedy graduated Harvard in June of 1940, his first book, Why England Slept , was on its way to the reading public. He hustled hard promoting his book -- and his big idea: Democracies had to be armed and ready to fight at all times, he said, the United States included.

Radio Announcer (archival audio): Good evening ladies and gentlemen. At this time we're indeed pleased to have with us in our studios, Mr. John F. Kennedy. This young man has a clear-headed, realistic, un-hysterical message for his countrymen, and for his elders.

John F. Kennedy (archival audio): We must realize that we must always keep our armaments equal to our commitments. We cannot tell anyone to keep out of our hemisphere unless our armaments and the people behind these armaments are prepared to back up the command even to the ultimate point of going to war...

Narrator: The book was timely; Americans were beginning to wonder if Hitler's military could reach the United States. Why England Slept became a surprise best-seller. His father was near preening about Jack's literary success, a first in the Kennedy clan. When the Duchess of Kent told the Ambassador she thought the boy was awfully young to be writing a serious book, Joe said simply, "my experience is that my sons are very precocious."

They were headed in different directions, Jack and his father, on account of this war in Europe. The German Army had already occupied Paris, and appeared to be headed toward London, and Joe Kennedy was still advising President Roosevelt to keep the U.S. out of the fight. This was England's war, he said, and one they were likely to lose.

Roosevelt was actively distancing himself from his wayward Ambassador; by the time Joe Sr. was recalled from London, reporters on both sides of the Atlantic were calling him a Hitler apologist, a defeatist.

David Nasaw, Historian: Joe Kennedy returned in disgrace and in the minority. And at some point he decided he was going to make a speech defending his position. Joe had dozens of people he could have called on: journalists, newspapermen, historians, researchers. He had professional speechwriters working for him. But he asked Jack to do it.

Jack Kennedy wasn't a puppet. He didn't swallow his father's beliefs, and he said to him: You can talk about the need for compromise and for negotiations, but say over and over and over again that you hate Nazism, you hate fascism, you hate Hitler. And don't use the word isolationist or appeaser.

Joe eventually gave that speech, and he followed some but not enough of his son's recommendations, and ended up further on the outs with the Roosevelt administration.

Joe Kennedy, Sr. (archival): Of course there's a risk in any course of action. But all doubts as to what is the best thing we can do should be resolved in the one statement, how can we best keep out of war?

Evan Thomas, Writer: Jack initially defended his father's isolationism. But as time went on, he realized that the United States needed to help Britain, to get in the game, to fight for freedom. His father was dead set against American intervention; Jack becomes for it.

Newsreel (archival): Air cadet Joseph P. Kennedy Jr. reports for preliminary training. With other college men, he'll try for Navy wing...

Narrator:The older Kennedy boys were doing more than talking war in 1941. Joe Jr. signed on as a flier for the Navy, even though the U.S. had not yet entered the fight. Jack was no less keen to get his shot at glory, if war came. But he was unable to get past the military doctors. His poor health was impossible to miss.

Robert Dallek, Historian: When he was 20 years old he began using steroids, and it reined in his colitis, but it had terrible side effects. And it also began to cause deterioration of the bones in his lower back. So, he was rejected, as someone who would be what was called 4F.

Robert Caro, Historian:He spends five months doing calisthenics, lifting weights, trying to build himself up enough. He still fails the examination. He tells his father that he has to arrange for him to have a special medical exam, which basically means a fixed medical exam, to clear him so he can get into the Navy.

Narrator: The new ensign was assigned to Naval Intelligence in Washington, where he became an instant, if minor, celebrity. The Ambassador's son found himself at cocktail hours and dinner parties with Senators, Admirals, foreign diplomats, newspaper publishers. They all wanted to know what the boy author thought about the big question of the day: should the U.S. get into the war?

Franklin D. Roosevelt (archival audio): The sudden criminal attacks perpetrated by the Japanese in the Pacific provide the climax of a decade of international immorality. Powerful and resourceful gangsters have banded together to make war from a whole human race... Their challenge has now been flung at the United States of America.

Narrator: After Pearl Harbor, America needed warriors like never before, but Kennedy remained at safe remove, in Naval Intelligence. When he finally, with the help of family connections, landed an assignment to train with a new combat unit -- PT boats -- he pronounced himself "delighted."

Robert Caro, Historian: Now, you know, PT boats, they're known as the bucking broncos of the Navy because they're very light-hulled, and they skim so fast over the waves, so that each wave is a bounce. Each wave is a jolt. The men who served with it said he was always in pain.

Robert Dallek, Historian: This was rough service and it was terrible on his back. Nevertheless, he perseveres and gets assigned to the South West Pacific, which is where the action is, fighting the Japanese.

Narrator: Kennedy arrived in the Solomon Islands in the spring of 1943, and took command of a 56-ton attack boat, PT-109. He liked his 12-man crew, but was unimpressed by the higher-ups.

Michael Dobbs, Writer: He was a very junior officer out in the Pacific. He was on the margins of the war. But he saw how a military operated not from the top down but from the bottom up. And one of his favorite expressions was, "The military screws up everything."

Narrator: PT-109's skipper did little to distinguish himself in his first four months on duty. He and his men ran raids on Japanese supply convoys; they were shot at and they fired back, but steered clear of major incident... until a hot, starless night that August. Out on a routine mission, Kennedy had his vessel idling in open water, when a Japanese destroyer emerged out of the darkness, racing at 40 knots, and split his boat in half. Two of his crewmen were killed immediately.

It took Kennedy nearly three hours -- swimming around in the dark -- to gather the survivors onto what was left of his PT boat. His engineer, Pappy McMahon, was badly burned, in excruciating pain, and helpless.

They were still stranded in open water at daybreak. Mid-afternoon, what was left of PT-109 was beginning to sink, and it looked like they had been left for dead.

Robert Caro, Historian: They're drifting, holding onto the hull and drifting in the water, when he sees a group of islands about three miles off. He tells them they have to swim to it to survive. But how is McMahon going to swim? McMahon is wearing a life jacket. Kennedy takes one of the straps, cuts it, puts one end in his teeth, tells McMahon to lay on his back, and then he tows him the three miles to this island. And when he gets up on the beach he collapses.

The men who were with Kennedy that day, they all speak of his sense of responsibility, that it was his job, that he would spare no effort to try and get help for his crew.

Narrator: It took a week, but Kennedy did manage to get his crew rescued. "Fortunately," he wrote to his father, "they misjudged the durability of a Kennedy."

He made it out alive a few months later -- sent Stateside for medical reasons-- and when he arrived at his parents' winter home in Palm Beach his weight was down to around 120. His back was so bad, he needed a brace and a cane to walk. But he was also a war hero; the Navy had made a public display of putting two medals on his bony chest.

And the story of PT-109 made great copy read by millions.

Robert Dallek, Historian: The country needs heroes at this point in the war. And so Jack, in a sense, fulfills that role.

Here is this wealthy son of the famous ambassador to Britain, who didn't have to go into this kind of combat service, and they don't talk about the fact that maybe his seamanship was in some ways deficient, in that his boat was cut in half. His brother, who was in London as an aviator, wrote some letters to him that were kind of demonstrating in a subtle way how envious he was.

Narrator: Joe Jr., of course, was not going to be outdone by his kid brother. He volunteered for a dangerous bombing run across the English Channel, in spite of the fact that he had already flown enough missions to earn a pass home. Just minutes into that secret mission, Joe's bomber exploded over the English countryside. His body was never recovered.

"Joe's worldly success was so assured and inevitable," Jack wrote, "that his death seems to have cut into the natural order of things." While Jack remained stoic, as always, the depth of his father's despair was unsettling. "There is something about the first-born that sets him a little apart," Joe Sr. wrote, "You know what great things I saw in the future for him, and now it's all over."

David Nasaw:Historain: The thought never comes to Joe Sr. or anybody else in the family that now that Joe Jr. has been killed, Jack's got to step in and become the leader of the family and run for political office and become the standard bearer for the Kennedy family, because no one thinks Jack is well enough in 1944.

He's skeletal. You can't imagine that this man isn't dreadfully, dreadfully sick. And the pain from his back is such that he cannot stand up, sit down, lie down. It's unimaginable that he will be able to campaign for office, or hold office.

John F. Kennedy (archival audio): Like many decisions in life, a combination of factors pressed on me, which directed me into my present profession. Period. I was at loose ends at the end of the war, comma, I was not very interested in following a business career.

Narrator: John Kennedy hinted in later years that he had entered politics to please his father, but friends who knew him best suspected the engine that drove Jack was his own.

When the Congressional seat once held by his grandfather and namesake, John Francis Fitzgerald, came open at the end of 1945, Jack jumped in feet first; he didn't mind if it antagonized every Democrat in the district who had dutifully waited his turn, which it did.

"You're not going to win this fight," one ward boss told Kennedy to his face. "You don't belong here."

Robert Dallek, Historian: He's seen as a kind of carpetbagger, an interloper. He didn't live in Boston and his opponents in the primary attack him for being a rich boy.

Narrator: Even his best supporters -- even his own father -- wondered if Jack had it in him to challenge the local Democratic machine, or to win in a field of better-known candidates. His health was still lousy -- "yellow as saffron, thin as a rake," one friend said. "He didn't seem built for politics," admitted another.

Robert Dallek, Historian: His father of course brings into the picture some of the very experienced Boston pols, and they see him as a work in progress. How is this really skinny guy, who doesn't seem all that eager to clap hands and "press the flesh," as they say, how are we going to convert him into a winning candidate?

David Nasaw, Historian: They sigh when they see this kid. He looks like a high school student. The major impediment to Jack is that he's not a very good candidate in the beginning. He's shy. He's withdrawn. He doesn't like going up to strangers or shaking hands. He talks much too fast when he gives speeches. Can't look at his audience. His voice is too high-pitched.

Robert Caro, Writer: He used to often read from a prepared text, and he would do it in a mechanical way. They were so afraid that he would forget his speech that his sister Eunice once sat in the front row, mouthing the words like a -- like an opera prompter.

Narrator: Long odds or no, Joe Kennedy poured money into his boy's race in 1946; he paid for thousands of hand-painted yard signs, advertising in print and radio, a professional polling operation. He distributed 100,000 copies of the New Yorker article about Jack's war heroics. "With the money I spent, I could have elected my chauffeur," he liked to joke. But his pride in his oldest remaining son grew as the campaign unfolded.

Robert Caro, Writer: His father is watching him one day, standing at the gates of a factory. And this mob of factory workers come out. Jack is standing there shaking hands, asking for votes, and the father is standing across the street with a friend. And he says, "I never in a million years thought Jack could do that."

David Nasaw, Historian: He taught himself -- with the help of lots of money from his father, and voice coaches, and political coaches -- he taught himself how to be a candidate. He taught himself how to look at the people he was talking to, how to speak slowly.

He spent twice as much time talking to the local parish and the boys' clubs and the veterans' clubs and the women's clubs. Whoever invited him, he went. He never, ever, ever stopped.

Robert Caro, Writer: This is a man who's wearing this canvas-covered steel brace all the time. And on long days of campaigning, that's not enough to try and hold himself up. So he has an Ace bandage, and he wraps it in a figure eight around his thighs and his back to give him extra support.

And this is the neighborhood of three-deckers. So if you want to knock on doors, which is what politics was then, you had to climb over and over again, one building and then the next. And he couldn't climb stairs in a normal way. What Jack Kennedy had to do was do it one step at a time. He put his foot on the next step and then pulled his other leg up. And these old pols would see him climbing these steps over and over, and never complaining. And they'd say, "How're you feeling? You're not feeling too good?" He said, "I'm feeling fine."

Narrator: He campaigned from sunrise to midnight, house to house, pub to pub, factory gate to factory gate, until he crumpled in a heap at the Bunker Hill parade -- on the eve of the primary. Some of the staff thought he was having a heart attack. Joe Kennedy told them to give him his medicine, and get him ready to campaign the next day, Election Day. He'd be fine.

Jack won going away, nearly doubling the second-place finisher's vote total in the primary, and now a lock to win the general election in the heavily Democratic district in the fall. The kid was a winner after all.

His likes had rarely been seen on Capitol Hill; he looked a kid -- skeleton thin, with wrinkled khakis, sneakers, seer-sucker jackets, shirttails hanging out. And he lived like one. He was always running late; left a trail of clothes and unfinished meals in his Georgetown townhouse for his valet to clean up. He showed up at his office as little as possible; took scant interest in constituent services and only middling interest in his committee assignments.

Robert Dallek, Historian: He's very bored by the day-to-day duties of a congressman, and he felt that he really didn't have significant power.

Narrator: He spent his evenings racing to movie theaters in his convertible, jockeying with the Washington trolley, a different girl in the passenger seat every night. Was it a movie star, the newspapers wondered? A socialite? Another airline hostess?

Robert Dallek, Historian: He's a playboy. He's a handsome young man. He wins that office when he's 29 years old, and he's really a celebrity. And he's enjoying himself. It was a period of great self-indulgence.

Evan Thomas, Writer: Even as he's this reckless, glamorous, playful youth, there was a kind of vulnerability. It's there.

Narrator: In the middle of the 1947 recess, a half-year into his first term, the young Congressman traveled to Britain to see his favorite sister Kathleen. "Kick," as the family called her, was the Kennedy most like Jack: independent, rebellious, full of fun.

During the visit Jack collapsed. The diagnosis was grim: a malfunctioning of the adrenal glands called Addison's disease. A doctor in London gave him a year to live. He crossed the Atlantic in a ship's hospital. The family told reporters waiting at the dock that Jack was suffering from a flare-up of malaria he'd contracted in the South Pacific.

The good news was, Joe Kennedy could afford the latest medicine -- and there was a new treatment for Addison's, a potent cortisone-based steroid. It got him out of his death-bed and bought him time. He told one friend he hoped for maybe 10 more years.

Eight months later, as he was beginning to regain his strength, 28-year-old Kathleen died in a plane crash.

David Nasaw, Historian: Jack was devastated. He'd loved Kick. It was the first time in his life really, and maybe the only time, where he didn't know what to do.

Timothy Naftali, Historian: It did make him a fatalist. He sent the signals of a kind of person who suspected that his time on earth was limited, and that he had to make the most of it.

Evan Thomas, Writer: He's lost a brother. He's lost his sister Kick. He himself has been near death. There is a sense of mortality that lurks in there but also drives him, that he's got to accomplish something before he dies, that life is finite.

Narrator: In his second and third terms in Congress, John Kennedy seemed like a new man: a man in a hurry, always on the lookout for ways to distinguish himself. He exploited his experience in foreign affairs and defense policy: got himself invited to Senate hearings as an expert witness on the military readiness of our European allies; criticized President Harry Truman for inadequate civil defense preparations in the wake of the Russians' first successful atom bomb test.

Robert Dallek, Historian: What interested him was the question of the rising tensions with the Soviet Union, with the civil war in China, with what was happening in Greece and Turkey, and how Harry Truman was responding to the dangers flowing out of the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe.

David Nasaw, Historian: One of the great advantages of having a very rich father who's willing to spend whatever his sons ask for is that you can go on your own fact-finding missions. You can travel the world. And Jack does that twice in 1951. He talks to the journalists and the military men. He talks to world leaders and he talks to the opposition.

Narrator: For seven weeks, the young Congressman traveled through Israel, Iran, Pakistan, India, Singapore, Thailand, French Indo-china, Korea and Japan. He returned home with a new insight: the United States was making few new friends in those places, and losing old ones. And Jack Kennedy went on national radio and television to deliver the message.

Announcer (Meet the Press, archival): Meet the Press! Our guest of the afternoon will be Congressman John F. Kennedy of Boston.

Reporter (Meet the Press, archival): What do we do in Indo-China then?

John F. Kennedy (Meet the Press, archival): Well we've tied ourselves completely with the French and after all the natives are anxious. You can never defeat the Communist movement in Indo-China until you get the support of the natives and you won't get the support of the natives as long as they feel the French are fighting the Communists in order to hold their own power there, and I think we shouldn't give them...

David Nasaw, Historian: Joe Kennedy had been invited to be on Meet the Press early on. He said, "No, I don't want to do it, but why don't you invite my son?" At the time no junior Congressman had ever been on. Only the biggest of the biggest stars in Washington were on Meet the Press. But Jack went on.

Lawrence Spivak (Meet the Press, archival): Mr. Kennedy, when I was in Boston last week I heard a good deal of talk about you. Many who thought that you would be the Democratic nominee for the Senate this year against Henry Cabot Lodge. Are you going to run?

David Nasaw, Historian: When Jack told his friends and his colleagues, "I'm going to run for the Senate against Henry Cabot Lodge," they were unanimous in saying: Don't do it. Nobody can beat a Lodge in Massachusetts. And Lodge is as handsome as you are, speaks as well, is as rich, and is a war hero. Don't even try.

Robert Dallek, Historian: This is a very storied family. As the old saying went up in Boston, where the Lodges speak only to Cabots, and the Cabots speak only to God. And so, can he defeat this Republican? And especially in 1952, it's a Republican year.

Timothy Naftali, Historian: His closest advisors told him, "Don't do it. This isn't your time. Maybe you should run -- think about running for governor of Massachusetts." No, no, no. He wanted to run for Senate.

John F. Kennedy (archival): This is a great state with a great past and I believe an even greater future. If elected to the United States Senate, with all of my energies and all of my resources I will fight to secure that future for the people of this state and for the future of our country... oh shit... And I know that it is not a one-way street...

Narrator: Whether 34-year-old John Kennedy was ready or not was an open question in the spring of 1952.

John F. Kennedy (archival): And if elected to the Senate of the United States this November I will fight for the New England industry, which is so vital... Uh, can you cut that?

Narrator: An uphill race against Henry Cabot Lodge was just the sort of challenge the Kennedys liked. "Run Jack," was the word at the family compound. "You'll knock his block off."

The most gleeful warrior in the clan was Jack's younger brother: 26 years old, barely out of law school, hungry to prove himself. Jack took a chance on brother Bobby, and put him in charge of the campaign.

Evan Thomas, Writer: Bobby Kennedy had always wanted a role in the family, and he found one. He was the tough guy.

Robert Dallek, Historian: He does not mince words. He's someone who is intent on winning this office for his brother, and if it means stepping on toes, hurting people's feelings, so be it.

Evan Thomas, Writer: Bobby was able to come in and discipline the old hacks who were hanging around the campaign office, tell them to get off their duffs and go out and knock on a few doors, get rid of the ones who were truly useless. He passed around old Joe's money, put down the politicians they wanted to get rid of, made the deals that had to be made. Bobby's doing all the hard work, the dirty work, and it's liberating to Jack.

Jack was able to float up there, quoting poetry and being a sort of young Lancelot.

Narrator: The Kennedy campaign was not shy to exploit the special appeal of the young Congressman -- the young bachelor Congressman. His mother, his sisters, even Bobby's bride, Ethel, fanned out into parlors across Massachusetts, to sell Jack to a rising new bloc of voters.

Jean Kennedy Smith, Sister: Women were not so involved as they are today, of course. And I think they were very struck by the fact that we were wandering around, trying to get them to get out and vote and get their friends to vote.

Jack came at the end and gave a very good speech. And people were very interested in him because they knew he was a hero, and he was young, and so they were very interested in how he did all this, and what he looked like and everything. He was a very easy candidate to sell, because he was good-looking, he had enormous charm, he had a great sense of humor. I mean, he was a real star.

Narrator: The polls showed Jack trailing the incumbent Senator as Election Day neared, but he was working hard to close the gap.

The demand of campaigning statewide -- the distances traveled across the rough Massachusetts highways -- was punishing, especially on Jack. "His mental courage is so much superior to his physical strength," Joe Kennedy wrote. "I sometimes wonder what the final result will be." Joe had another fear about his son's health: if Jack's Addison's disease became public, it could cost him the race, maybe even his political future.

Evan Thomas, Writer: Jack was losing weight. But the Kennedys said, "Well, it's just the campaign." Jack Kennedy always had a suntan. Well, they said, "Well, he's out and he's getting a suntan." Actually, that was from his treatment, cortisone treatments for Addison's, that darkened his skin. They covered all that up.

Timothy Naftali, Historian: A man who focuses on the word "vigor" in his public and private conversations must have in mind a sense of vitality, human vitality, as an ideal. Imagine the distance between the reality of his own physical troubles and his ideal of the vigorous, vital leader. Such a smart man would know this distance and understand the gap between reality of his own physical being, and the image he wanted to project.

Narrator: Jack kept working down to the wire. He still started his day earlier than his opponent, traveled more miles, campaigned later into the night. He would not allow himself to lose for lack of effort.

Newscast (archival audio): In Senate races, Representative John F. Kennedy scores one of the few major Democratic victories, decisively defeating in a tough battle the Republican incumbent Henry Cabot Lodge Jr.

John F. Kennedy (archival): Well, I guess you're glad it's over, aren't you Bobby?

Robert F. Kennedy (archival): I am, Jack.

John F. Kennedy (archival): OK.

Narrator: They were beginning to be seen together around town soon after he entered the Senate in 1953, two dazzling stars in Washington's normally dull firmament. Jack Kennedy was 35 years old, the most sought-after bachelor in the capital. Jacqueline Bouvier was a shy 23-year-old beauty, the belle of Manhattan, Easthampton and Newport. The couple had met at a dinner party two years earlier and had been warily circling one another ever since.

Sally Bedell-Smith, Writer: She was engaged when she met him, and she broke it off very quickly. She wrote in her diary that she had an intimation that Jack would have a profound and possibly disturbing effect on her life. But he was worth it. She once said to her sister that to her, imagination was the most important thing she wanted to find in a man, and she said that's very difficult to find.

From his standpoint, she was very different from the women that he'd known, which were primarily his own sisters. Eunice and Pat and Jean were what one of his friends said "tawny, coltish women." They were energetic and they were athletic and they were outspoken. Jackie, by contrast, was cerebral and soft-spoken and they both had a kind of dry and sly wit.

Narrator: The romance was carried out largely in the public eye, and when Jackie agreed to marry the Senator in the summer of 1953, the press was invited to share the joy.

Sally Bedell-Smith, Writer: They were so beautiful. They were so young. She was very stylish. Somebody in the New York Times wrote that she made the world safe for brunettes again.

David Nasaw, Historian: Jackie was smart, gorgeous, and although she had not been born into a political family, she knew precisely what to say.

Sally Bedell-Smith, Writer: Jack's closest friend, Lem Billings, actually warned her before they were married that she was going to be marrying a man who was known for his womanizing, and that it was unlikely that he would stop. And she later said that instead of being put off by what Billings said, she actually viewed it as kind of a challenge.

Narrator: "After the first year, Jackie was wandering around looking like the survivor of an airplane crash," a friend later remembered. Her new husband did not go out of his way to hide his dalliances from her. Jack Kennedy treated this as a matter of personal liberty, and betrayed little guilt. "He had this thing about him," said the man who introduced the Kennedys, "which was not under control."

And it wasn't just his womanizing that stunned Jackie. "Politics was sort of my enemy," she confided. "We had no home life whatsoever."

Edward R. Murrow, CBS News (archival): Let's go and meet the newlyweds. Are you there, Senator?

John F. Kennedy (archival): Yes, right here, Mr. Murrow.

Edward R. Murrow, CBS News (archival): Good evening, sir.

John F. Kennedy (archival): Thank you.

Edward R. Murrow, CBS News (archival): Good evening, Mrs. Kennedy.

Jacqueline Kennedy (archival): Good evening.

Edward R. Murrow, CBS News (archival): I understand that the two of you had a very much publicized...

Narrator: Whatever her misgivings, Jackie Kennedy had married a politician, and she dutifully accepted her role.

Edward R. Murrow, CBS News (archival): And you first met the Senator when you interviewed him?

Jacqueline Kennedy (archival): Well, I interviewed him shortly after I met him.

Edward R. Murrow, CBS News (archival): Well now, which requires the most diplomacy? To interview senators or to be married to one?

Jacqueline Kennedy (archival): Um, well...

John F. Kennedy (archival): Being married to one, I guess [laughs]...

Narrator: Over on Capitol Hill, however, the Kennedys' star power had less appeal. The young Senator's way of being set Democratic leader Lyndon Johnson's teeth to grinding.

Thomas Hughes, Aide to Sen. Hubert Humphery: Johnson looked at Jack as a person who picked and chose what he would like to do in the Senate. And the picking and choosing wasn't Johnson's idea of how the Senate ran, nor was it the idea of the other southern moguls who were in charge. Kennedy was the troubadour who came and played before the banquet and left before the dishwashing began. And I think Lyndon talked about him in exactly those terms.

Robert Caro, Writer: Johnson says Kennedy was pathetic as a Congressman and Senator. He didn't know how to address the chair, by which he meant he didn't even know the rules.

Narrator: What irked Johnson was that he couldn't depend on the man. Kennedy was often absent; he ducked the controversial censure vote on Joe McCarthy. And Kennedy's insistence on independence was maddening for the Majority Leader. Whether it was civil rights or labor legislation, Johnson couldn't count on the Democrat from Massachusetts to vote the party line.

Lyndon Johnson could be cutting about Kennedy in front of fellow Senators -- said he looked like a victim of rickets, and joked about his puny little ankles. What Johnson didn't see, was how tough Jack Kennedy had to be just to get out of bed in the morning. By 1954, the drug he took to control his Addison's disease was eating away at his spine.

Robert Dallek, Historian: It came to a point that in order for him to walk from his office to the Senate floor, he had to move across a marble floor, and it was so hard on his back, he needed crutches to allow him to put one foot in front of another, without excruciating pain. And so what he decides to do is to have surgery, even though it is a danger to his life.

Robert Caro, Writer: It requires the fusing of two large sections of the spine and a steel plate inserted there. What makes it risky is that he has Addison's disease. And Addison's disease leads to infections often during surgery.

David Nasaw, Historian: His father pleads with him: Don't do this operation. And he holds out the example of Roosevelt. He said: "Roosevelt was President and he was in a wheelchair. You can do it."

Robert Caro, Writer: Jack said to him, "I'd rather be dead than be in a wheelchair or hobbling around on crutches, in pain the rest of my life."

David Nasaw, Historian: Jack goes ahead with the operation. Hours afterwards, an infection develops. Fever spikes. Last rites are performed.

Jack pulls out, and Joe has him flown to Palm Beach.

Narrator: He would suffer a series of setbacks in Florida. The eight inch incision on his back would not close; he developed an abscess, needed a second surgery. The convalescence dragged on into 1955.

David Nasaw, Historian: Joe watches over him, hires his doctors, his nurses, converts a large part of their Palm Beach house to a nursing facility, and encourages Jack.

Narrator: The Kennedys told reporters that Jack's back problems were a result of war injuries; they did not disclose his ongoing need of steroids, or his Addison's disease.

Jack, meanwhile, began work on a second book, a series of essays about United States Senators who had risked their political careers bucking convention and party for a greater purpose. With the help of Library of Congress research files, Kennedy, his speechwriter Ted Sorensen, and a handful of Senate staffers produced Profiles in Courage.

David Nasaw, Historian: For seven, eight months, Jack recuperates. And only after a lengthy period is he able to return to the Senate.

Interviewer (archival): How does it feel to be back?

John F. Kennedy (archival): Well I'm glad to be back here and have a chance to take part in what's going on. I'm sure my wife is too.

David Nasaw, Historian: He returns in pain. And he will remain in pain for the rest of his life.

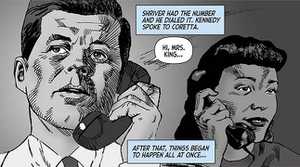

John F. Kennedy (archival audio): It is now my privilege to present to this convention, as a candidate for President of the United States, the name of a man uniquely qualified by virtue of his compassion, his conscience, and his courage...

Narrator: The 1956 Democratic presidential nominee, Adlai Stevenson, gave his party's youngest senator a starring role at the convention: the official nominating speech. And his performance helped ignite a Kennedy-for-Vice President boom.

Reporter (archival): How would you like to be Vice President with him?

John F. Kennedy (archival): Well, I'd be honored, of course, if chosen, but I've always had my doubts whether I'd even be chosen.

Narrator: He wasn't sure he even wanted a place on the ticket -- Joe Kennedy had counseled him to steer clear -- but Stevenson threw the choice to a floor vote, and Jack Kennedy had a hard time backing down from a challenge -- even against the better-known and esteemed Senator, Estes Kefauver. Jack Kennedy liked his chances, and he liked the feeling on the convention floor: the delegates took his candidacy seriously.

Robert Caro, Writer: This whole thing lasted like 24 hours, before the vice-presidential balloting. And Kennedy makes a real try for it.

Lyndon Johnson (archival audio): Texas proudly casts its vote for the fighting sailor who wears the scars of battle, and that very senator -- the next Vice President of the United States -- John Kennedy of Massachusetts.

Robert Caro, Writer: For a moment, it seemed actually like he's going to win. But Kefauver beats him. He has to make a concession speech to Kefauver. When he gets up there, he's facing a sea of Kefauver signs. They're all waving in his face. And you look at Kennedy, who's always immaculate. At this moment he is not immaculate.

John F. Kennedy (archival): Ladies and gentlemen. Ladies and gentlemen of this convention.

Robert Caro, Writer: In fact, one point of the collar of his shirt is sticking out. And as he's talking, if you watch his hands, he has the gavel in his hands and he restlessly he turns it around. You saw a young man in defeat, and you also see someone who covers it up so well.

John F. Kennedy (archival): I hope that this convention will make Estes Kefauver's nomination unanimous. Thank you.

Jean Kennedy Smith, Sister: Jack was very depressed, very upset. And Bobby was there. And he couldn't cheer him up. And he said, "Let's call Dad." So I remember when we all went to call Dad, and he said, "Congratulations!" he said to Jack. "That's the best thing that ever happened to you. That was magnificent. I don't know how you did that. Was absolutely great." He said, "Adlai Stevenson is going nowhere." He said, "He's going nowhere, and that's -- Kefauver's going nowhere. So you've just pulled it off, and I can't tell you how wonderful that was." And Jack came out beaming, beaming.

Narrator: Joe Kennedy knew what he was talking about. Stevenson lost big to Eisenhower, which made the Governor a two-time loser, and left the Democratic nomination wide open next time 'round.

Jack Kennedy understood the obstacles to winning the presidency in 1960 and they were not small. He was younger than anybody ever elected to the office. He had few legislative achievements to run on.

And, then too, there was his religion. In 1957, a quarter of the electorate still said they were unwilling to vote for a Catholic for President.

Kathleen Kennedy Townsend, Niece: There was a fear across the land that Catholics would be controlled by the Pope, that they couldn't think on their own, and therefore they weren't really really Americans in the way that Protestants were.

Narrator: Some in the party argued the country would change in time, that he was still a young man, that he could wait it out. Jack Kennedy thought otherwise. His star turn at the 1956 convention meant he would be taken seriously in 1960. He was not going to let this moment pass.

John F. Kennedy (archival): And I want to be sure that we haven't lost something important in this country, that we haven't gone soft...

Narrator: He had campaigned across the country for Stevenson in '56. John F. Kennedy (archival): ....that we just look to our own private interests... Let us cut the budget and let us save on foreign aid.

Narrator: And with his speechwriter Ted Sorensen riding shotgun he just kept going in 1957.

John F. Kennedy (archival): The reason the Communists attack us is because they know when the United States fails, the cause of freedom fails.

Narrator: There were county chairmen to meet in every state, delegates to woo.

Jackie was pregnant most of that year, and nervously so. She'd already had one miscarriage, and delivered a stillborn daughter. But her husband rarely stopped traveling. When Kennedy's new back specialist went to Palm Beach for a consultation, she, too, got the program.

Robert Caro, Writer: She comes down and there's this huge map of the United States, where his father and he are plotting out, you know, his next trips. He's traveling all around the United States, trying to make contact with politicians. And she says, "Well, you know, to do this you need periods of rest." And he says, "Well, there's no time for rest." And she says, "Well, you have to change the schedule." And he said, "The schedule will not be changed."

Narrator: When he was in Washington, Kennedy was always on the lookout for ways to take a stand apart from the other would-be Presidents in the Senate -- Stuart Symington, Hubert Humphrey, and above all, the majority leader, Lyndon Johnson.

Kenneth Harper (archival): This is a strike-breaking, union-busting bill, in my opinion.

John F. Kennedy (archival): Mr. Harper, this bill is not a strike-breaking, union-busing bill. You're the best argument I know for it, your testimony here this afternoon, your complete indifference to the fact...

Narrator: He dabbled in domestic issues where he saw opportunity, like in the nationally televised hearings into racketeering in the labor unions.

John F. Kennedy (archival): ... might tend to incriminate them. Your complete indifference to it, i think makes this bill essential..."

Narrator: His chief interest, and his focus, remained foreign affairs. His father even managed to talk Lyndon Johnson into giving Jack a coveted slot on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee.

Thomas Hughes, Aide to Sen. Hubert Humphery: When Kennedy said that he would become chairman of the African subcommittee in the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, he sort of got a commitment that it would never have to meet. And Johnson thought that was typical of the kind of committee that Kennedy would like to run.

Reporter (archival): Scenes like this are taking place daily all over Algeria, as French colonial troops round up natives by the thousands, in a desperate attempt to halt the guerrilla reign of terror that has spread the length and breadth of the colony. Sixty thousand...

Narrator: The bloody escalation of the three-year-old war for independence in Algeria gave Senator Kennedy a shot at the spotlight, and one that played to his long-held interest in foreign policy.

Robert Dallek, Historian: He identifies himself with a kind of anti-colonial posture, with the idea that the United States is locked in a contest with the Soviet Union for hearts and minds in the Third World, in the developing world, in Africa, in Asia, in Latin America. And he sees Algeria as the case study of the time.

John F. Kennedy (archival): I am concerned today that we are failing to meet the challenge of imperialism on both counts, both East and West, and thus failing in our responsibilities to the free world and to ourselves.

Timothy Naftali, Historian: What Kennedy was saying was: We know that French imperialism is going to die out. The question is: Are we going to be on the right side or the wrong side of history? If we make a choice now, we can help shape the outcome. If we align ourselves with Paris until the bitter end, the new generation of leaders in Algeria will remember that and won't talk to us.

John F. Kennedy (archival): I am introducing a resolution, which I believe outlines the best hopes for peace and a settlement in Algeria...

Harris Wofford, U.S. Commission on Civil Rights: Dean Acheson, the former Secretary of State, came out saying this speech was "the irresponsible utterings of a juvenile Senator," because it was throwing aside our alliance with Portugal and France and England, in support of Africa and Asia, etc.

Timothy Naftali, Historian: France was a NATO ally of ours in Europe. Were we going to abandon our ally for the sake of a group of revolutionaries who might turn out to be Communists? Kennedy said yeah, you take that chance, because you want to vote with the future, not with the past.

TV Host (archival): Senator, what do you feel is the single most critical issue facing the Congress at this time?

John F. Kennedy (archival): Well, I think it's the same issue which has been facing us for 10 years, and that's our relations with the Soviet Union and this question of war and peace and also the question of whether the uncommitted countries, the Middle East, Africa and Asia, will move to the Communist bloc or our own, and turn the balance of power for us or against us. And that's obviously the most important issue of the day and will be during, I think, our lifetime.

Richard Reeves, Writer: When Sputnik went up by the Russians the surprise could not have been greater. How did they get ahead of us? The Russians claimed they invented everything: the car, the plane, penicillin, whatever it was. The Russians would always say, "Oh no, we had that first." This, they had first, and they had proved it.

Narrator: The October 1957 launch of Sputnik, a 184-pound, beach-ball sized satellite, spurred an instant jump in Cold War hysteria, and not without reason. If the Soviets were able launch a satellite into space, could they also reach the U.S. with nuclear-armed missiles?

U.S. Air Force bombers went on 24-hour alert. The Eisenhower administration began sending extra planes into Soviet airspace, just to remind Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev who had the upper hand in bombers. When President Eisenhower pursued more -- and more potent -- nuclear warheads for the U.S. arsenal, the Soviets answered. Six in 10 Americans believed nuclear war was imminent, and would be catastrophic.

Kennedy appeared unruffled by the rising dangers of the Cold War; he increased his travel schedule, running harder, state to state, the list of delegates who had supported his Vice Presidential candidacy tucked in his pocket.

Robert Caro, Writer: Jack Kennedy could learn on the run. So he's traveling around the country, and he's seeing that politics is changing. He's learning that the power isn't back in Washington anymore; the power is with these younger people in the states, if he can just line them up for him. He's learning that the old party machinery doesn't work.

David Nasaw, Historian: He knows that he's got the money to mount an independent campaign; that he's got the charisma, without the help of any party bigwigs or any party establishment, to get his photo in on the cover of Time and the Saturday Evening Post and Look.

He begins a change in American politics that is quite significant. He signals the beginning of a move from party dominance and party candidates to the individual, to the personality, who can speak to the people not through the party but through television and the mass media directly.

John F. Kennedy (archival): It's a pleasure to have you here, and I want you to meet my daughter Caroline, and my wife Jackie.

Narrator: Joe Kennedy was nudging every editor he knew in 1959: You want to sell magazines? Put Jack and Jackie on your cover. Jackie Kennedy chafed at the requirement of public display, but when the photographers showed up on the Kennedy doorstep, she did not disappoint.

Thomas Hughes, Aide to Sen. Hubert Humphery: It used to drive Humphrey nuts, because he said, "Every time I go into the supermarket to go shopping for Muriel, I see Redbook or I see Good Housekeeping or I see Saturday Evening Post all with the Kennedys smiling at me on the cover."

William H. Lawrence, Journalist (archival): Senator, when are you going to drop this public pretense of non-candidacy and frankly admit that you already are seeking the Democratic presidential nomination of 1960?

John F. Kennedy (archival): Well, Mr. Lawrence, I think there's an appropriate time for anyone to make a decision and a final announcement as to whether he's going to be a candidate...

John Seigenthaler: Journalist: It seemed to me that there was a sort of perpetual half-smile on his face. There was a sense of joy about what he was doing, that he loved what he was doing.

Robert Dallek, Historian: He's only 43 years old. And a woman says to him, "Young man, it's too soon." And he says, "No, ma'am. This is my time."

John F. Kennedy (archival): I am today announcing my candidacy for the Presidency of the United States. The Presidency is the most powerful office in the free world. Through its leadership can come a more vital life for all of our people...

Narrator: Kennedy officially announced his candidacy in January of 1960. Political odds-makers put his chances well below Senators Symington, Humphrey and Johnson. And if the old rules applied, Kennedy was surely in trouble. The well-worn path to the Democratic presidential nomination went through the state party chairmen and the big city bosses, who still thought they could keep their delegations in line.

But Kennedy already had a handful of key players in every state, and a way to show himself a winner: the primaries. The handful of state primaries were regarded as side events before 1960 -- fine for junior senators like Jack Kennedy, but not worthy of serious candidates. Lyndon Johnson sat them out that year.

Thomas Hughes, Aide to Sen. Hubert Humphery: Johnson stayed in the Senate, stayed as majority leader, told everybody else who was leaving town that they should be ashamed of themselves and they should be back legislating, not speaking.

Robert Dallek, Historian: Johnson's supposition is that he's earned the nomination by dint of his role as Senate majority leader, he has very good relations with various party bosses across the country, and that Jack Kennedy is an upstart. "Who is this kid who's trying to displace me and take the nomination? I deserve it."

Hubert Humphrey (archival): Nice to see you. I'm Senator Humphrey, just stopping by to say hello...

Narrator: The most important early primary was in Wisconsin, where Kennedy had a real opponent: the popular Senator from neighboring Minnesota, Hubert Humphrey.

Hubert Humphrey (archival): Say, that's just what I need for my campaign, can I have that? I'm running short!

John F. Kennedy (archival): You should realize that you are voting for the most important individual in the entire free world...

Narrator: He cast Humphrey as the establishment candidate, and ran against the party bosses. And he cast himself, as the underdog, in spite of a huge advantage in money and television exposure, and having celebrity backers like Frank Sinatra.

Frank Sinatra, singing (archival audio): K-e-double n-e-d-y. Jack's the nation's favorite guy.

Everyone wants to back Jack. Jack is on the right track.

Come on and vote for Kennedy, vote for Kennedy. He'll keep America strong.

Kennedy, he just keeps rolling a-, Kennedy, he just keeps rolling a-, Kennedy, he just keeps rolling along!

Vote for Kennedy!

Sandy Vanocur, NBC News (archival): Senator, good evening.

John F. Kennedy (archival): Good evening, Sandy.

Sandy Vanocur, NBC News (archival): How does the evening look to you?

John F. Kennedy (archival): Well, as all election nights are it's a very interesting evening.

Narrator: He knew on Election Day he was going to win, but as the results came in and his margin was narrower than he'd expected, Kennedy began to understand there would be a caveat: the party elders could argue that his victory in Wisconsin owed to his overwhelming margin in the state's large bloc of big-city Catholic voters -- as if his religion had been an unfair advantage.

Robert Dallek, Historian: He understands, this is not enough. If he's going to win that nomination, he has to convince people in the Democratic Party and around the country that he can win Protestant votes, that he's more than just a Catholic candidate.

His sister, after the victory in Wisconsin, says to him, "Well, what does it mean?" He says, "It means we've got to go on to West Virginia." West Virginia is a state with 97% Protestant population.

Narrator: Humphrey started with a 20-point lead in West Virginia and the backing of the state's popular senator, Robert Byrd. He also got a new campaign theme song, the none-too-subtle anti-Catholic dog-whistle, "Give Me That Old Time Religion." The Kennedys answered in kind. Joe blanketed the state with money, buying the support of crucial local bosses. Bobby recruited Franklin Delano Roosevelt Jr., to allege that Humphrey had shirked his military duty in World War II.

Humphrey (archival): Jack Kennedy and I served in the United States Navy for five years...

Robert Dallek, Historian: And John Kennedy then dismisses this as a terrible thing to have been said about Hubert. And he keeps going around the state saying, "It's a terrible thing to say that Hubert's a draft dodger, a terrible thing," until it fastened itself on people's minds that Hubert maybe was a draft dodger.

Narrator: Kennedy left West Virginia on May 11th, 1960, with a win. He got in his private plane, outfitted to carry staff and press -- a first in presidential campaigns -- and flew off to primaries in Maryland and then Oregon, to pile up more delegates to take to the nominating convention that July.

Robert Caro, Writer: Jack Kennedy is going around the country. He's showing the country what he is: this charming, incredible, adept campaigner. The New York Times says, "The calliope sound of a bandwagon is being heard in the Democratic Party." All of a sudden Lyndon Johnson wakes up.

John Steele, Journalist, Time magazine (archival): Senator Jack Kennedy of Massachusetts has won every primary in which he's entered. He's won them in a breeze. Does this entitle him...

Lyndon Johnson, Senate Majority Leader (archival): Well Mr. Kennedy is a very effective and able young man.

John Steele, Journalist, Time magazine (archival): Let me finish my question. Does this entitle him to the Democratic presidential nomination?

Lyndon Johnson, Senate Majority Leader (archival): Well I wouldn't think that we would want to nominate our president on the basis of what four states or five states or six states or eight states might say in a limited primary system where only a few people participate...

Narrator: By the time he got around to announcing his candidacy for the Democratic presidential nomination, just a week before the party convention in Los Angeles, Johnson needed a miracle. So he pulled out his last best hope: he sent a private investigator to dig up Kennedy's health records.

Robert Dallek, Historian: They get to the Democratic convention in Los Angeles, and Johnson unleashes his aide, a man named John Connally, and Connally issued a story about Kennedy's Addison's disease, raising the question of whether Kennedy is physically capable of serving as president.

Narrator: That Jack Kennedy suffered from Addison's disease was a fact beyond dispute, but the Kennedys disputed it. "John F. Kennedy does not now nor has he ever had an ailment described classically as Addison's disease," Bobby claimed. The Addison's story didn't stick, but Johnson kept fighting anyway; he still couldn't believe Jack Kennedy, of all people, could take the nomination away from him.

Lyndon Johnson, Senate Majority Leader (archival): For six days and nights we had 24-hour sessions. Six days and nights I had to deliver a quorum of 51 men, on a moment's notice, to keep the Senate in session and to get any bill a'tall. I'm proud to tell you, that on those 50 quorum calls, Lyndon Johnson answered every one of 'em.

Although some men who would be president, on a civil rights platform, answered none.

John F. Kennedy (archival): Let me just say I appreciate what Senator Johnson had to say. He made some general references to, perhaps the shortcomings of other presidential candidates, but as he was not specific, I assume he was talking about some of the other candidates and not about me.

Narrator: Kennedy parried Johnson with the grace of a sure winner. Bobby, meanwhile, was working the phones, keeping a white-knuckle grip on his brother's committed delegates. He knew Johnson operatives were still trying to peel them away.

California delegate (archival): California casts seven and one half votes for Johnson, 33 and one half votes for Kennedy. John Seigenthaler, Journalist: The Kennedy campaign thought they had every hole plugged, and were aware that if something came unplugged, they wanted to be on top of it immediately.

Delegate (archival): Senator Kennedy, 104 and a half votes...

John Seigenthaler, Journalist: And every delegation was covered.

Delegate (archival): Wyoming's vote will make majority for Senator Kennedy.

Delegate (archival): "The motion is that the rules be suspended and that John F. Kennedy be nominated for President of the United States by acclimation!"

Robert Caro, Writer: The next morning at 6:30, the phone rings in Bobby Kennedy's suite. It's his brother. He says, "Count up how many votes we have if we take the Northeast, the eastern states, plus Texas." Bobby Kennedy calls in two of his top advisors, Ken O'Donnell and Pierre Salinger. He says to them, "Count up these votes, plus Texas." Salinger, as he recalls, says, "You're not thinking of nominating Lyndon Johnson. You can't do that!"

Narrator: Kennedy knew how Johnson talked about him: "Little Johnny," or "Sonny Boy," "heard his pediatricians have given him a clean bill of health." And he knew his brother Bobby despised Johnson. But hatred was one of the few luxuries Kennedy could not afford -- not in picking a running mate. The numbers said he needed to win Texas to win the presidency, and there was one man who could deliver the state.

Harris Wofford, Campaign Aide: Robert Kennedy tried to stop it. He went down to try to persuade Johnson not to accept it, that the opposition to him was too great.

Thomas Hughes, Aide to Sen. Hubert Humphery: I remember how haggard Bobby looked, Johnson obviously had told him that he didn't want to speak to his brother's spokesman, he wanted to speak to his brother. If Jack had anything to say, he can call me. Here's my phone number.

Walter Cronkite, CBS News (archival): Senator Kennedy announced his choice is Senator Lyndon Baines Johnson of the state of Texas, the Senate majority leader, and his foremost rival for the presidential nomination...

Thomas Hughes, Aide to Sen. Hubert Humphery: There are many compartments in Jack's mind. I think the main one was that he wanted to win.

News announcer (archival audio):And there is the presidential candidate. The senator John Kennedy of Massachusetts. As he comes out of The Biltmore Hotel we come to his car. This morotcade will drive the three miles out here to the colleseum...

Narrator: John F. Kennedy had never lost an election, and now, against all odds, at age 43, he was just one win away from the Presidency. He was confident he could get there. What the American voters craved, Kennedy had come to understand, was a good story. And the set piece Kennedy would campaign on in the general election had it all: good versus evil; freedom versus slavery; a youthful paladin -- that would be himself -- and his powerful antagonist -- the Soviet Premier, Nikita Khrushchev, who proved the perfect foil in 1960.

John F. Kennedy (archival): For the world is changing. The old era is ending. The old ways will not do. Abroad the balance of power is shifting. New and more terrible weapons are coming into use. One third of the world may be free, but one third is the victim of a cruel repression, and the other third is racked by poverty and hunger and disease. Communist influence has penetrated into Asia. It stands in the Middle East and now festers some 90 miles off the coast of Florida.

Robert Dallek, Historian: Khrushchev had come to the United States and the United Nations sessions in September of 1960, banged the shoe on the desk, and said, "We will bury you." We are grinding out missiles like sausages. So there was a heightened sense of competition. And this appealed to Kennedy's competitive spirit.

Richard Nixon, Vice President (archival): And I say we can't afford to have the White House as a training ground for an inexperienced man.

Narrator: Kennedy was certain he could show himself the better man in a race against the sitting Vice President, Richard Nixon.

John F. Kennedy (archival): I am not satisfied as an American to be second to the Soviet Union in sending a missile to the moon or sending Sputnik around the globe or having the second strongest arms...

Narrator: The polls, however, showed a dead heat coming out of the conventions, and Kennedy could not shake free from the mire of religion. He watched with increasing ire as Protestant ministers across the country stirred opposition among their parishioners. The Reverend Martin Luther King Sr. said he could not in good conscience vote for a Catholic. He instructed his flock to vote for Nixon.

Kathleen Kennedy Townsend, Niece: Oh it was very nasty. Let's just be blunt about it. For a while, he didn't really want to have to deal with it. He just wanted people to look at him and judge him on his own record. But it was getting so virulent and so scary that he then, in the fall campaign, went to Houston and spoke to the ministers, went sort of into the belly of the beast as it were.

John F. Kennedy (archival): Reverend Meza, Reverend Rock, I'm grateful for your generous invitation to state my views...

Timothy Naftali, Historian: His advisors said, "Don't do this. You are just making religion an issue. You are actually speaking to the bigots. The bigots want you to remind people that you're a Catholic. Don't do this!"

He did it.

John F. Kennedy (archival): So it is apparently necessary for me to state once again -- not what kind of church I believe in, for that should be important only to me -- but what kind of America I believe in. I believe in an America where the separation of church and state is absolute.

Kathleen Kennedy Townsend, Niece: He was making sort of a moral, ethical argument about what it means to be American.

John F. Kennedy (archival): And this is the kind of America I fought for in the South Pacific and the kind my brother died for in Europe. No one suggested then that we might have a divided loyalty, that we did not believe in liberty, or that we belonged to a disloyal group that threatened, I quote, "the freedoms for which our forefathers died"...

Kathleen Kennedy Townsend, Niece: And he said, "We would hate to have a country that millions of people who, on the day they're baptized, are told they can't be president of the United States."

John F. Kennedy (archival): So I want you to know that I'm grateful to you for inviting me tonight. I'm sure that I have made no converts to my church, but I do hope that at least my view, which I believe to be the view of my fellow Catholics who hold office, I hope that it may be of some value, in at least assisting you to make a careful judgment. Thank you.

Narrator: The general election campaign of 1960 featured a new wrinkle: the first ever one-on-one debates between the major party candidates, broadcast live, across the nation.