Part One: The Quest

Narrator: Richard Nixon was one of the most important American presidents of the second half of the 20th century -- and also the most controversial.

Interest in him seems only to increase with time. Nixon books abound. He himself wrote ten and largely about himself. He has been described and dissected by historians, political scientists, political biographers, psychobiographers, and by other politicians. There's been a Nixon opera and a Hollywood film, with Anthony Hopkins in the title role.

This program is the first full-scale documentary biography, a three hour film drawn from archival footage and interviews with the real people.

This is the actual story of the president who rose to power as a strident anti-communist and who, once in office, reached out to the two great communist powers of the world, the Soviet Union and China. He was puzzling, contradictory, very difficult to know, heartily disliked, and acclaimed by the American people in two elections. He was also the first and only president to resign from office. His tragic unmaking, of course was Watergate. But why? How could it have happened to someone so politically astute and by reputation, so keenly intelligent?

Heraclitus, the Greek philosopher of the sixth century B.C., said, "A man's character is his fate."

MILITARY AIDE: [Farewell Press Conference, August 9, 1974] Ladies and gentlemen, the President of the United States of America and Mrs. Nixon, Mr. and Mrs. David Eisenhower, Mr. and Mrs. Edward Cox.

NARRATOR: On August 9, 1974, Richard Milhous Nixon became the first President in the history of the United States to resign from office. His staff gathered in the White House to bid him farewell, as millions of Americans watched on television, some in sorrow and disbelief, others glad to see him go. Richard Nixon had accomplished great things as President and had been reelected overwhelmingly, but he was also widely distrusted, sometimes ridiculed, even despised.

President RICHARD MILHOUS NIXON: [August 9, 1974] You are here to say goodbye to us and we don't have a good word for it in English. The best is au revoir. We'll see you again.

JOHN EHRLICHMAN, Nixon Campaign Staff: Richard Nixon was studiedly different to different people. And I don't think there's any one person, including his wife probably, who could sit down and write the definitive explanation of Richard Nixon. We all saw him differently.

NARRATOR: He was a tireless campaigner, a survivor of more than a quarter of a century of political battle, yet so self-conscious that he disliked shaking hands and found it hard to look anyone in the eye.

Mr. NIXON: [campaigning for Congress] And I intend to continue to expose the people that have sold this country down the river until we have driven all the crooks and the Communists and those that defend them out of Washington, D.C.

NARRATOR: He rose to power as a crusader against Communism, only to make his most lasting mark building bridges to China and the Soviet Union.

He had millions of admirers all over the world, but trusted almost no one and in the end was left to face his enemies alone. The advice he offered his staff in his last speech as President stirred the thick August air with admonitions that seemed to apply most aptly to Nixon himself.

Pres. NIXON: [August 9, 1974] Always give your best. Never get discouraged. Never be petty. Always remember others may hate you, but those who hate you don't win unless you hate them and then you destroy yourself.

ELLIOTT RICHARDSON, Nixon Cabinet Member: It struck me from time to time that Nixon, as a character, would have been so easy to fix, in the sense of removing these rather petty flaws. And yet, I think it's also true that if you did this, you would probably have removed that very inner core of insecurity that led to his drive. A secure Nixon almost surely, in my view, would never have been President of the United States at all.

Part One: The Quest

NARRATOR: Richard Nixon was born in the tiny Southern California desert town of Yorba Linda in 1913. He grew up among the people he would one day call "forgotten Americans," and "the silent majority," hard-working, church-going people, farmers, shop keepers, people with an inbred respect for authority and an unyielding belief in the American Dream.

Pres. NIXON: [August 9, 1974] I remember my old man. I think that they would have called him a sort of a little man, a common man. He didn't consider himself that way. You know what he was? He was a streetcar motorman first and then he was a farmer and then he had a lemon ranch and then he was a grocer. But he was a great man.

NARRATOR: "Richard had his father's fire," his mother, Hannah Milhous Nixon once said, "and my tact." She seemed the opposite of the loud, aggressive husband her Quaker family always believed beneath her: soft-spoken, tightly controlled, never allowing anger to get the better of her. She insisted her second son be called "Richard," not "Dick," taught him to read before he entered school and made sure he said his prayers daily and went four times to Quaker meeting on Sundays.

SECOND-GRADE TEACHER: I taught Richard Nixon in the second grade here in Yorba Linda. He sat in the back seat and always came to school with a white starched shirt with long sleeves. He was always a quiet, dignified little fellow and a very good student.

NARRATOR: He was clumsy, but dogged at games, shy but gifted at reciting poetry and full of his father's enthusiasm for politics.

MERLE WEST, Cousin: Dick was politically inclined as a kid. I remember walking to school and I think it was when Harding was running for President and old Dick was there on a stump, saying why everybody should vote for Harding.

NARRATOR: The Nixons moved to nearby Whittier when Richard was nine. Founded by Quakers in 1887, it was a sober, industrious community, no liquor stores, no bars, no dance halls. Frank Nixon bought a gas station along the highway and soon added a general store where the whole family worked, often 16 hours a day seven days a week.

Mr. NIXON: One thing my mother and dad always used to say when we were growing up -- I don't mean my mother because she was a little biased -- but my dad used to say when we were growing up, he said, "You know, you boys" -- speaking to me particularly -- "you boys have got to get out and scratch. You're not going to get anywhere on your good looks."

NARRATOR: When Richard was 12, his younger brother Arthur suddenly fell ill and died. And within eight years, Harold, the eldest brother and family favorite, would succumb to tuberculosis. Hannah Nixon recalled, "It was Arthur's passing that first stirred within Richard a determination to help make up for our loss by making us very proud of him. He may have felt a kind of guilt that Harold and Arthur were dead and he was alive," she remembered.

Pres. NIXON: [August 9, 1974] My mother was a saint and I think of her, two boys dying of tuberculosis, nursing four others and seeing each of them die and when they died, it was like one of her own. Yes, she will have no books written about her, but she was a saint.

NARRATOR: "I would like to study law and enter politics for an occupation," Nixon wrote in the eighth grade, "so that I might be of some good to the people." Nixon worked hard for everything he got and his sober, industrious air sometimes put off his contemporaries. When he ran for class president at Whittier High, he lost to a candidate he later dismissed as "an athlete and personality boy." He would not lose another election for 30 years.

Both Harvard and Yale invited Nixon to apply for scholarships, but his dream of a prestigious Eastern university was frustrated. It was 1930, the Great Depression and Harold was in the midst of his long struggle with tuberculosis. "We needed Richard at home," Hannah Nixon remembered. Nixon had to settle for Whittier College just down the road and later said he'd never felt disappointed. He soon became a big man on the small campus.

He was an ambitious student politician, an accomplished actor, a champion debater. The Whittier student body elected Nixon president in 1933. He was both admired and resented for what one student called, "an almost ruthless cocksureness." The exclusive Franklin Club denied Nixon membership. He helped organize a competing club, the Orthogonians or square-shooters, students who took pride in working their way through college. They wore no ties, served spaghetti and beans and attracted the college's best athletes.

Nixon later denied there was any class distinction between his shirt-sleeved Orthogonians and the tuxedo-ed Franklins, but throughout his life, he would emphasize the differences between his own modest beginnings and the wealthy, privileged backgrounds of his political opponents.

The Important Thing is to Win

NARRATOR: Duke Law School was Nixon's next training ground in persistence, success and frustration. His classmates called him "Gloomy Gus." He lived frugally, studied endlessly and never walked away from a classroom confrontation.

LYMAN BROWNFIELD, Duke Classmate: We had a professor of torts, Douglas Maggs who was so intimidating that most people backed down. The first person in our class that I remembered that stood up to him and kind of barked back was Nixon. And he had the-- he'd stand there, kind of flat-footed and you could just see he was dug in. And he was just standing up to Maggs, kind of almost shaking in his shoes, but by gosh, he wasn't going to back down.

NARRATOR: Nixon graduated third in his class, hoping for a job with an East Coast law firm or the FBI, but his applications were rejected. He went back home to Whittier. Nixon's mother helped him get a job in a friend's law office, but small-town law bored him and he was still too young and inexperienced for state politics.

Then, while auditioning for a local play, he fell in love. Pat Ryan was a truck farmer's red-haired daughter, ten months older than he and even more accustomed to hard work and hardship. She had worked her way through college as a switchboard operator, salesgirl and movie extra before taking a teaching job at Whittier High. "Don't laugh," Nixon told her, even before their first date, "but someday I'm going to marry you." He pursued Pat for over two years, even driving her to Los Angeles on weekends when she had dates with other men, then waiting around to take her home again. He married her in June of 1940, but his political ambitions would have to wait five more years. The world was at war.

Eight months after Pearl Harbor, Nixon joined the Navy and as a lieutenant commander, was sent to the Solomon Islands. He was best remembered for his skill at scrounging food and liquor and supplies for the grateful men, who called him "Nick." And he learned to play poker, not just to fill the time, but to make some extra money.

JAMES STEWART, Navy Officer, World War II: He said to me, "Do you think that there's any sure way to win?" And I said, "Well, if you don't think you have the best hand going in, get out. Drop. Don't ante up." I said, "The trouble with that is that you'll probably drop three or four hands out of five and it's very boring and I haven't got the patience to do it." Well, to our intense surprise, he did exactly that. And he won quite more frequently than he lost and he sent home to California a fair amount of money, I have no idea exactly how much, but my estimate was between $6,000 and $7,000.

NARRATOR: It was his poker winnings that helped finance Nixon's first political campaign. At war's end, he was approached by a group of Republican bankers and businessmen from Whittier who sought a candidate to unseat the five-term Democratic congressman, Jerry Voorhis. Voorhis, a Yale graduate from a wealthy family, was anathema to Whittier Republicans. He supported labor, opposed big oil and big banking and championed the social welfare programs of the New Deal. Lieutenant Commander Nixon jumped at the opportunity to run against him.

Leading Republicans around Whittier were confident they finally had found the man to defeat Jerry Voorhis. "Nixon comes from good Quaker stock," a local banker wrote, "He is a very aggressive individual." Another partisan said, "This man is saleable merchandise." In his first campaign, Nixon developed an approach that remained remarkably consistent through nearly three decades. The candidate presented himself as a family man from a long tradition of work and service, a firm believer in individual initiative, a champion of the forgotten man. And at the same time, he proved to be a fierce, no-holds-barred combatant, accusing Voorhis of ties to Communist organizations distorting Voorhis' record in Congress.

JERRY VOORHIS: [1971 Interview] Just before the election, a good many people came and told me, "Do you know about the telephone calls that were being made?" and I said no, I didn't. "Well," they said, "I was called on the phone by an unidentified person, who simply said that, "Do you know that Jerry Voorhis is a Communist?" and "You should vote for Mr. Nixon because of this fact."

NARRATOR: The character of Nixon's campaign surprised many of his friends. "Of course, I knew Jerry Voorhis wasn't a Communist," he later told a Voorhis aide, "but I had to win. That's the thing you don't understand. The important thing is to win."

Mr. VOORHIS: All the stops were pulled and Mr. Nixon beat me. He was a good debater, he was a clever debater. I wouldn't deny that at all, but I still feel that there were a good many below-the-belt blows struck in the campaign.

NARRATOR: Nixon was swept into office with 60 percent of the vote, part of a nationwide Republican surge. His boyhood goal to enter politics had been achieved.

The Concealed Enemy

1st NEWSCASTER: Capitol Hill in Washington is again the nation's focal point as the 80th Congress convenes during one of the most crucial periods in the nation's history. The Republican-controlled Congress takes the helm in the House.

NARRATOR: As the Nixons posed beneath the cherry blossoms with baby Tricia, it was a heady time for a young Republican. The GOP controlled both houses of Congress for the first time in 20 years and the fervent anti Communism that had helped Nixon win the election was well-suited to the times.

2nd NEWSCASTER: Soviet Russia was expansively stabbing Westward, knifing into nations left empty by war. Already, an iron curtain had dropped around Poland, Hungary, Yugoslavia, Bulgaria.

MAN: [testifying before HUAC] I am not now a communist--

NARRATOR: And in the United States, the House Committee on Un-American Activities searched for Soviet sympathizers. Congressman Nixon soon became the junior member of that controversial, headline-making body.

And on August 3, 1948, shortly after the birth of Nixon's second daughter, Julie, an unlikely drama began that would make the issue of Communist subversion front-page news and make Congressman Nixon a national figure almost overnight.

[Chambers taking oath]

A strange, self-confessed ex-Communist and editor of Time Magazine, named Whittaker Chambers, appeared before the committee to make a sensational charge. Alger Hiss, protege of Oliver Wendell Holmes, aide to Franklin Roosevelt at Yalta and one of the organizers of the United Nations was, said Chambers, a Communist intent upon infiltrating the highest offices of government.

WHITTAKER CHAMBERS: [testifying] Mr. Hiss represents the concealed enemy against which we are all fighting and I am fighting.

ALGER HISS: [testifying] My contacts with any foreign representative who could possibly have been a Communist have been strictly official.

NARRATOR: Most observers found Hiss persuasive, but Nixon had learned through Father John Cronin, a Catholic priest with FBI connections, that Hiss had been under suspicion for years. Nixon insisted the hearings continue.

3rd NEWSCASTER: "Who's the liar?" might well be the title of the drama which unfolds before a packed caucus room where the House Un-American Affairs Committee members swear in Alger Hiss.

NARRATOR: The hearings were high drama. Rumors spread that Chambers was a psychopath. Hiss claimed never to have known him. President Truman denounced the proceedings as politically motivated and ordered government agencies to refuse to cooperate. Nixon charged that the Democrats were mounting a cover-up. The freshman congressman from Whittier had put himself in the center of it all.

RALPH de TOLEDANO, Early Nixon Biographer: Nixon realized that once he had committed himself, that if everything collapsed, if Hiss was exonerated or if the charges were not proved to the hilt, he would be badly hurt. Now, I don't think he would have been permanently hurt, but certainly, I think if that had happened, Richard Nixon would never have become a senator and never would have become President of the United States.

NARRATOR: "He immersed himself in the case with an absorption that was almost frightening," Pat Nixon remembered. When others were ready to drop the case, Nixon and chief investigator Robert Stripling talked them out of it. They were sure Hiss was lying when he claimed not even to have known Chambers and they set out to prove it.

ROBERT STRIPLING, Chief Investigator, House Committee on Un-American Activities: We went up and got Mr. Chambers, put him in the grand jury room, we put him under oath and we said, in effect, "You claim you know Mr. Hiss? Tell us all about him. What did he call his wife? What did she call him? Did they have a dog? Dc they have a veterinarian? Did they have a doctor? Did they have a cook? Give us the housekeeping details, beginning at the front door." And he'd rattle on for two hours. It was very obvious that he, indeed, did know Mr. Hiss and quite well.

Mr. RALPH de TOLEDANO, Early Nixon Biographer: There was also another factor and which I think is very important and that was a kind of personal animus. Hiss was arrogant on the stand and he rubbed Nixon the wrong way and he snapped at Nixon a couple of times and so on. And it became, I think, also a personal thing for Nixon. He saw that it could be a big issue and his whole temperament made him want to pursue it.

Mr. CHAMBERS: [testifying] I believe that I was first introduced to Mr. Hiss by Harold Ware and J. Peters.

NARRATOR: Chambers, now fighting a libel suit, leveled a still more sensational charge, one he had not yet shared with the committee. He claimed that Hiss had actually been a spy before the war, copying secret State Department documents which Chambers himself had passed on to a Soviet contact. Nixon was furious that Chambers had been holding out on him. He ordered any evidence Chambers might have subpoenaed, then left with his wife on a long-delayed Caribbean vacation.

4th NEWSCASTER: In the latest sensational turn of the Red espionage probe, the Maryland farm of the magazine editor becomes the focus of attention.

NARRATOR: From a hollowed-out pumpkin, Chambers produced apparent proof of espionage: microfilm of stolen documents. Nixon made the nation's front pages when he was plucked from mid-ocean and flown back to Washington for a press conference.

Representative NIXON: I am holding in my hand a microfilm of very highly confidential, secret State Department documents. These documents....

NARRATOR: The microfilm, thereafter known as "The Pumpkin Papers," provided the evidence and the publicity Nixon needed. Finally, after two controversial trials, Hiss was found guilty of perjury and imprisoned. The Hiss case polarized American opinion about Richard Nixon. To conservatives, he had fearlessly rooted out a dangerous subversive, but in the eyes of many liberals, Nixon had destroyed an honorable man and set the stage for more unscrupulous Communist hunters. But there was no doubt that, at the age of 35, the congressman from Whittier had become a national figure.

The Pink Lady

NARRATOR: 1950. The Russians had exploded an atomic bomb of their own. Julius and Ethel Rosenberg were charged with giving the Soviets atomic secrets. Communists took control of mainland China. In Korea, Communist troops poured across the 38th parallel and American soldiers were sent to stop them. Senator Joseph McCarthy charged that Communists in government were responsible for it all.

Senator JOSEPH McCARTHY: And call the roll. And call the roll of the traitors who plunder.

NARRATOR: And Congressman Nixon had his sights on the Senate. His opponent was three-term Congresswoman Helen Gahagan Douglas. Like Herry Voorhis, she was wealthy, well-educated and an outspoken New Dealer. She condemned the fear of internal Communism as "irrational" and opposed the very existence of the House Committee on Un-American Activities.

Politicians in both parties called the former actress "a bleeding-heart liberal, a do-gooder, a Hollywood parlor pink." Congressman John F. Kennedy quietly gave Nixon $1,000 to help defeat her, saying, "It won't break my heart if you can turn the Senate's loss into Hollywood's gain."

Mrs. Douglas was a perfect target for what Nixon called his "rocking, socking style" of campaigning. Implying the congresswoman was pro-Communist, he distributed a flyer on pink paper, showing Mrs. Douglas had voted with the controversial left-wing Congressman Vito Marcantonio 354 times. The fact that most Democrats and a good many Republicans had voted the same way was ignored. Nixon charged that his opponent was "pink right down to her underwear." Mrs. Douglas fought back hard, calling Nixon "a peewee who is trying to scare people into voting for him," and she gave him the nickname he would never entirely shake, "tricky Dick."

HELEN GAHAGAN DOUGLAS: [1979 Interview] When Richard Nixon ran for the House of Representatives and unseated Jerry Voorhis, it was the same kind of campaign as he waged against me in 1950, but the essence of that kind of campaign is this: to avoid the issues, you work up bogus issues, trying to play on the fears of people because if you talk about the real issues, you may lose votes. It's as simple as that.

NARRATOR: Other candidates employed scare tactics that year, but few were more blatant than Richard Nixon's. "People react to fear," he once told an aide, "not love. They don't teach that in Sunday School, but it's true." Nixon defeated Mrs. Douglas by almost 700,000 votes, the largest plurality won by any Senatorial candidate in the country.

Senator NIXON: [1950] A lot of people probably wonder how it is possible for a candidate to be elected to any office in California when he is a member of the Republican Party. I have just had that experience and I should like to point out the reason for our election victory. It's because in this particular election, the issues, rather than the partisan labels of the candidates, were what governed the electorate.

ROGER MORRIS, Nixon Biographer: Richard Nixon does not simply defeat Jerry Voorhis for the Congress or defeat Helen Gahagan Douglas for the Senate in 1950, he destroys these people politically and very nearly personally. And he does that in such a way as to leave a great legacy of bitterness among their supporters and even among onlookers, people who were sort of neutral observers on the side.

A Nixon Republican

5th NEWSCASTER: Chicago is a city divided, as thousands of delegates and observers stream into the city for the 25th Republican Convention. Partisanship runs high and the trappings of the Grand Old Party dominate the scene before the serious business gets under way.

NARRATOR: After only a year and a half in the Senate, Nixon was a leading candidate for the vice presidential nomination.

5th NEWSCASTER: And here comes "Mr. Republican" himself, Senator Robert Taft.

NARRATOR: Taft partisans, mostly conservative and isolationist, applauded Nixon's fervent anti-Communism, while General Eisenhower's more liberal, internationalist backers were attracted to Nixon's support of the Marshall Plan, his commitment to rebuilding post-war Europe. The California delegation was pledged to its favorite son, Governor Earl Warren, but behind the scenes, Nixon lobbied hard for the nomination of Eisenhower.

Mr. RALPH de TOLEDANO, Early Nixon Biographer: He was a man with no set ideology, no set -- real deep-down principles. He wasn't a Taft Republican, he wasn't an Eisenhower Republican, he was a Nixon Republican.

6th NEWSCASTER: With New York's big block of votes, the issue is no longer in doubt and a wildly-cheering convention hails its nominee, Dwight D. Eisenhower, soldier and statesman.

NARRATOR: Away from the convention floor, Eisenhower huddled with Nixon. The young senator represented the growing power of the West Coast and he was a rough-and-tumble campaigner. The general offered him the vice presidency.

Sen. NIXON: [1952 Republican Convention] And as we contribute to the Republican cause, what we will do is to forge a great victory for the Republican Party next November, but a victory which will be a victory not only for the Republican Party, but what is more important, it will be a victory for America and for the cause of free peoples throughout the world.

NARRATOR: Eisenhower intended to keep to the high road, he told his new running mate. It was up to Nixon to flail the Democrats and their presidential candidate, Adlai Stevenson.

Sen. NIXON: [campaigning] There is no question in my mind as to the loyalty of Mr. Stevenson, but the question is one as to his judgment.

Many good Americans are concerned by the way that President Truman and Governor Stevenson have both attempted to ridicule and pooh-pooh the Communist threat within the United States.

You read about another bribe, you read about another tax-fix, you read about another gangster getting favors from the government. The people are sick and tired of it. They're outraged and they want something done about it and they're tired of an Administration which, instead of cleaning up, is covering up the scandals in Washington at the present time.

NARRATOR: Suddenly, Nixon faced a scandal of his own. The New York Post reported that wealthy supporters had set up a secret fund for Nixon's personal use.

Sen. NIXON: And if that were true, let me say, first of all, that I should never have accepted the nomination to the vice presidency of the United States and if it were true, I would get off the ticket right away, but it is not true.

NARRATOR: In fact, the fund was not secret and was earmarked exclusively for political expenses, but the damage had been done. Aides urged Eisenhower to drop Nixon from the ticket. Even Republican newspapers demanded he resign.

HANNAH NIXON, Mother: When those headlines first came in the paper, I just wanted to hide that paper. I didn't want anyone to see it. I couldn't eat and I knew that it wasn't true, but what could I do?

PATRICK HILLINGS, Campaign Staff: Well, when the world seemed the blackest and the whole Nixon campaign had halted in Portland, Oregon, I got a telegram from his mother. I took it into him and gave it to him and he was sitting in a large chair with his arms on the side, almost like the Lincoln statue that you see in Washington, the Lincoln Memorial. And I handed him the telegram and he read it and he dropped it on his-- in the chair and his head fell forward and the tears came down his eyes. And it was obvious that he'd been terribly moved by what all this meant, that it was so important to him to prove to his mother that he'd never done anything wrong.

NARRATOR: Was Nixon on or off the ticket? General Eisenhower had been frustratingly silent. Finally, after three days of waiting, a weary, anxious Nixon received Eisenhower's phone call.

TED ROGERS, Nixon Television Adviser: And he said, "General," he said, "I'm just Richard Nixon." And he said, "I'm just a very young guy that doesn't know you very well. But," he said, "I must tell you, General, that there comes a time, even in your life, when you have to shit or get off the pot."

Mr. PATRICK HILLINGS, Campaign Staff: And there was this dead silence and we didn't know whether the ballgame was over right then or not, but Eisenhower seemed to take it as it was meant to be given and came to the conclusion, as he told Nixon on the phone -- he reported to us after the conversation -- that Nixon should go to California and make a nation-wide speech explaining all the details of this so-called "secret fund" and that he would authorize the National Committee to pay for the cost.

NARRATOR: Nixon secluded himself in Los Angeles and prepared to use the young medium of television as it had never been used before. He would bypass the press, bypass even Eisenhower and plead his case directly to the American people. This primetime broadcast would come to be known as the "Checkers" speech and widen the gap between Nixon's admirers and his detractors. To some, he seemed humble, honest, sincere; to others, self-righteous and shamelessly manipulative.

Sen. NIXON: ["Checkers" speech] My fellow Americans, I come before you tonight as a candidate for the vice presidency and as a man whose honesty and integrity has been questioned. And so now, what I am going to do and incidentally, this is unprecedented in the history of American politics -- I am going at this time to give to this television and radio audience a complete financial history, everything I've earned, everything I've spent, everything I owe.

KENNETH BALL, Whittier Neighbor: I don't remember talking to his mother, but his father, he thought that he really did all right. He said, "I hated to hear him say some of the things he said, but he told the truth and that's what the people wanted to hear and that did the job for him."

Sen. NIXON: ["Checkers" speech] First of all, we've got a house in Washington which cost $41,000 and on which we owe $20,000. We have a house in Whittier, California which cost $13,000 and on which we owe $3,000. My folks are living there at the present time.

NARRATOR: His wife asked him, "Why do you have to tell people how little we have and how much we owe?" "People in political life have to live in a goldfish bowl," he answered, "but I knew it was a weak explanation for the humiliation I was asking her to endure."

Sen. NIXON: ["Checkers" speech] I should say this, that Pat doesn't have a mink coat, but she does have a respectable Republican cloth coat. And I always tell her that she'd look good in anything.

NARRATOR: The "cloth coat" remark was aimed at the Truman Administration, then plagued by mink-coat bribery charges. Next, Nixon borrowed a technique from Franklin Roosevelt. He talked about his dog.

"Using the same ploy as FDR," he wrote in his memoirs, "would irritate my opponents and delight my friends."

Sen. NIXON: ["Checkers" speech] We did get something, a gift after the election. It was a little cocker spaniel dog, black and white spotted. And our little girl Tricia, the six-year-old, named it Checkers.

And you know, the kids, like all kids, love the dog and I just want to say this right now, that regardless of what they say about it, we're going to keep him.

[Republican Rally, Cleveland, Ohio] I would do nothing that would harm the possibility of Dwight Eisenhower to become President of the United States and for that reason, I am committed to the Republican National Committee, tonight through this television broadcast, the decision which is theirs to make. Wire and write the Republican National Committee whether you think I should stay on or whether I should get off and whatever their decision is, I will abide by it.

General DWIGHT DAVID EISENHOWER: [defending Nixon] I have been a warrior and I like courage. And tonight, I saw an example of courage.

GOP CHAIRMAN: [Cleveland Rally] All those in favor of Nixon continuing as a candidate will say aye!

AUDIENCE: Aye!

Mr. LYMAN BROWNFIELD, Duke Classmate: I had called some Republican friends of mine and had asked them to send telegrams to Nixon, saying, "Don't drop off the ticket," and they had refused. And I was with some of them when I watched the "Checkers" speech and afterwards, every one of them sent a telegram to Nixon, saying, "Great job, stay on the ticket."

NARRATOR: Nixon stayed on the ticket that was swept into office in November, the first Republican administration in two decades.

Mr. PATRICK HILLINGS, Campaign Staff: During the Eisenhower years, Nixon became the point man. Eisenhower never expected to have to get into too much political discussion, but that was one of the reasons he put young Senator Richard Nixon on the ticket, because he could do that. So all the tough political assignments usually were given to Nixon.

Sen. NIXON: [campaigning] All a Democratic Congress offers, if elected this year, is a return to the policies of the Truman Administration.

Mr. ROGER MORRIS, Nixon Biographer: He's a very partisan creature, after all, and he becomes for the first time really, the focus of genuine criticism in the press. He has enjoyed enormous immunity in the press in Southern California and nationally up until the '52 campaign. And he suffers his first tarnish in the fund episode and that gets worse and worse, until Herblock begins to give him a heavy beard in cartoons in the Washington Post and he comes under sometimes vicious, often very telling and accurate, attack in the national media.

7th NEWSCASTER: A stunned nation hears that its President is stricken with a heart attack.

NARRATOR: Nixon's detractors held their breath during Eisenhower's illness in September 1955, but the Vice President surprised even his most severe critics. For nearly two months, Nixon was a cautious substitute president, standing in for Eisenhower, while not calling attention to himself.

Vice President NIXON: The American people can be assured that the business of government will go ahead as usual, despite the President's illness. Under the President's leadership, a team has been developed in Washington which will carry out the very well-defined foreign policies and domestic policies that the President himself has laid down during his first two and a half years in office.

NARRATOR: Fully recovered, Eisenhower announced he would seek reelection, but did not guarantee Nixon a place on the ticket. Privately, he thought him immature, a political liability. But Nixon refused to consider the President's offer of a cabinet position instead of the vice presidency.

He finally forced Eisenhower's hand.

Vice Pres. NIXON: I met with the President this afternoon in the White House and at that time, I informed him that in the event that he and the delegates to the Republican National Convention decided that it was in the best interests of the Republican Party and his Administration for me to continue in my present office, that I would be honored to accept renomination as the Republican candidate for vice president.

PRESS SECRETARY: And the President has asked me to say that he was delighted to hear of the Vice President's decision.

Vice Pres. NIXON: [1956 Republican Convention] No man could be more highly honored than to be selected as the running mate of such a great President. I accept this nomination in that spirit.

NARRATOR: Nixon was less aggressive in 1956 than in earlier campaigns. The press began to write of a "New Nixon," but the Vice President remained the Democrats' favorite target.

ADLAI STEVENSON, Democratic National Candidate 1956: I must say bluntly that every piece of scientific evidence we have, every lesson of history and experience indicates that a Republican victory tomorrow would mean that Richard Nixon would probably be President of this country within the next four years. I say frankly, as a citizen more than a candidate, that I recoil at the prospect of Mr. Nixon as custodian of this nation's future, as guardian of the hydrogen bomb, as representative of America in the world, as commander-in-chief of the United States Armed Forces.

8th NEWSCASTER: As evening returns come in, the trend is unmistakable. It's Eisenhower by a landslide, with 457 electoral votes to 74 for Stevenson and a nine-million vote plurality.

Vice President NIXON: I, Richard M. Nixon do solemnly swear--

NARRATOR: Nixon was a survivor. He had overcome Eisenhower's indifference, a sometimes hostile press and bitter partisan attacks. He entered his second vice presidential term as the Republican heir apparent.

The Bronze Warrior

NARRATOR: Richard Nixon was favorite to win the Republican presidential nomination in 1960. Events of the last four years had made him one of the most visible Vice Presidents in history. During a tour of South America, he had faced down angry leftist mobs that spat upon him and his wife and attacked their motorcade. Maintaining his composure throughout the ordeal, Nixon returned home to a hero's welcome. And in Moscow, he had confronted the leader of the communist world, Nikita Khrushchev, in an impromptu televised debate.

Vice Pres. NIXON: There must be a free exchange of ideas. There are some instances where you may be ahead of us, for example, in the development of your-- of the thrust of your rockets for the investigation of outer space. There may be some instances -- for example, color television -- where we're ahead of you, but in order for both of us-- [Khrushchev interrupts] for both of us to benefit-- for both of us to benefit-- you see, you never concede anything.

NARRATOR: Nixon's combination of toughness and humor played well back home. In July 1960, Republicans embraced him as their presidential candidate.

MAN: --that Vice President Richard M. Nixon has been unanimously nominated to be the candidate of the Republican Party for the office of President of the United States.

NARRATOR: Just 14 years after he was tapped by a group of small-town businessmen to run for Congress in California, Richard Nixon stood at the top of his party. As he mapped out an ambitious 50-state campaign, he was challenged by his opponent, John F. Kennedy, to a series of televised debates, the first in American history. Even when hospitalized for two weeks with a knee injury, Nixon remained confident, anxious for the debates to begin, eager once again to use television to talk directly to the voters.

HERB KAPLOW, NBC News: At the time, there was a feeling that this, overall, might be a mismatch. Nixon was the candidate who had more prominence, who had been a member of the House, a member of the Senate and the Vice President of the United States. Kennedy, he didn't have a particularly strong reputation in Congress. There was some feeling that he was, to some extent, a playboy, that he wasn't too serious a senator and so, I think people felt that Nixon had the edge and I think Nixon felt that he had the edge.

HOWARD K. SMITH, Moderator: The candidates need no introduction: the Republican candidate, Vice President Richard M. Nixon and the Democratic candidate, Senator John F. Kennedy. According to the rules set by the candidates themselves each man --

NARRATOR: The Nixon-Kennedy debates would forever change the way Americans chose their Presidents. Political rallies and old-fashioned hand-shaking became much less important than the image on the television screen.

Mr. TED ROGERS, Nixon Television Adviser: You must understand that Nixon himself had said, "I don't want any makeup on for these particular debates." What I tried to explain to Dick was he has these certain characteristics of his skin where it's almost transparent. And it was a very nice thought to say, you know, "I don't want any makeup," but that he really needed to have what we would have called even an acceptable television picture. And of course, JFK, here he'd been riding in motorcades all over California with the top down. He looked like a bronze warrior when he came into Chicago. He really did.

Senator JOHN FITZGERALD KENNEDY: [Nixon-Kennedy debate] Mr. Nixon comes out of the Republican Party. He was nominated by it. And it is a fact that through most of these last 25 years, the Republican leadership has opposed Federal aid for education, medical care for the aged.

Vice Pres. NIXON: I know what it means to be poor. I know what it means to see people who are unemployed. I know Senator Kennedy feels as deeply about these problems as I do, but our disagreement is not about the goals for America, but only about the means to reach those goals.

NARRATOR: The first debate was costly to Nixon. The radio audience thought he had won, but the largest television audience in history had seen the Vice President haggard and drawn and had been given its first sustained look at the Kennedy style.

HERB KLEIN, Nixon Press Secretary: Kennedy had a great charm for not only the voters, but also for the press. The press corps had sort of a love affair with Jack Kennedy and no matter what things we might do to make things better -- we could serve a hot meal, they would serve a cold meal and the press liked cold better -- and so that he felt he was running up against impossible odds.

Vice Pres. NIXON: And I say we can't afford to have the White House as a training ground for an inexperienced man who is rash and impulsive.

Sen. KENNEDY: This Administration has failed to recognize-- has failed to recognize that in these changing times, with a revolution of rising expectations sweeping the globe, the United States has lost its image as a new, strong, vital revolutionary society.

Vice Pres. NIXON: I have been to Russia and I've seen it. I've been to the United States and I've seen it. And there is no need for a second rate psychology on the part of any American.

1st REPORTER: Mr. Vice President, what did you think of your reception today?

Vice Pres. NIXON: Well, of course, it was the greatest of the campaign and I think this means that we're on the way to victory in New York.

1st REPORTER: [to Pat Nixon] How about you? Do you agree?

PAT NIXON: Oh, it was wonderful.

NARRATOR: Election night, Nixon remembered, was the longest night of his life. It appeared at first to be a Kennedy sweep, then became too close to call, then edged back toward Kennedy again.

Vice Pres. NIXON: [1960 election concession speech] And I--please, please. And I-- as I look at the board here, while there are still some results still to come in, if the present trend continues, Mr. Kennedy-- Senator Kennedy will be the next President of the United States.

I just -- and I want--excuse me.

SUPPORTERS: [chanting] We want Nixon! We want Nixon! We want Nixon!

Vice Pres. NIXON: Thank you very much.

NARRATOR: In the end, it proved to be one of the closest elections in history. Kennedy won by only 100,000 votes and charges of Democratic fraud were widespread. Much of the winning margin came from Lyndon Johnson's Texas and Richard J. Daley's Chicago, but Nixon refused to demand a recount.

"If it failed to change the results," he wrote "charges of 'sore loser' would follow me through history and remove any possibility of a further political career."

Mr. ROGER MORRIS, Nixon Biographer: Richard Nixon is forever embittered by the experience and -- taken with the example, I think -- feels that never again will he be caught short, never again will his opponents outdo him and never again will he trust the ordinary, normal and honest devices of American politics to function as they're supposed to.

NARRATOR: In his last official act as Vice President, Nixon presided over a joint session of Congress on January 6, 1961 and announced his own defeat.

Vice Pres. NIXON: I now declare that John F. Kennedy has been elected President of the United States and Lyndon Johnson Vice President of the United States.

President-Elect KENNEDY: [taking oath of office] I, John Fitzgerald Kennedy, do solemnly swear that I will faithfully execute the office of President of the United States and will, to the best of my ability, preserve, protect and defend the Constitution of the United States, so help me God.

Oblivion

Mr. PATRICK HILLINGS, Campaign Staff: Well, he handled it surprisingly well. In fact, he cheered us up a good deal of the time. He was still a very young man. I'm sure he had thoughts of the future. The biggest problem was that the fellow who defeated him was a young man and all of us thought that meant at least eight years for Jack Kennedy and what is Nixon going to do for eight years?

Vice Pres. NIXON: [announcing gubernatorial candidacy] I shall not be a candidate for President of the United States in 1964. I shall be a candidate for governor of the State of California in 1962.

NARRATOR: But Nixon had been out of touch with his home state for too long. The campaign against incumbent governor Pat Brown was bitter and exhausting. Nixon was soundly defeated. Reporters in Los Angeles were told the losing candidate had left and would not make a statement, but Nixon, his anger toward the press building for years, resolved to have the last word.

Vice Pres. NIXON: For 16 years, ever since the Hiss case, you've had a lot of fun, a lot of fun. And you've had an opportunity to attack me and I think I've given as good as I've taken. I leave you gentlemen now and you will now write it, you will interpret it, that's your right. But as I leave you, I want you to know-- just think how much you're going to be missing.

You don't have Nixon to kick around anymore. Because, gentlemen, this is my last press conference and I hope that what I have said today will at least make television, radio, the press, recognize that they have a right and a responsibility, if they are against a candidate, give him the shaft, but also recognize, if they give him the shaft, put one lonely reporter on the campaign who will report what the candidate says now and then. Thank you, gentlemen and good day.

NARRATOR: An angry, resentful Richard Nixon strode from the Beverly Hilton on November 7, 1962, seemingly bound for political oblivion. "Barring a miracle," said Time Magazine, Richard Nixon's political career was over.

Part Two: Triumph

NARRATOR: Less than six months after his humiliating defeat in California, Nixon appeared on The Jack Paar Show, playing a tune he had written himself. Although no one in the audience could have known it, this was the beginning of one of the most remarkable comebacks in American political history.

JACK PAAR, Host: Can Kennedy be defeated in '64?

Vice Pres. NIXON: Well, which one? Just to be very serious, I know, of course, you're referring to President Kennedy and I under no circumstances would speak disrespectfully even of him or of his office.

Mr. PAAR: Aren't you kind of friends? Were you kind of friends at one time?

Vice Pres. NIXON: Oh, certainly. We came to the Congress together--

Mr. PAAR: I know you were.

Vice Pres. NIXON: --and we were low men on the totem pole on the Labor Committee together. And we remained low men until he ran for President. Now he's up and I'm down.

Mr. PAAR: My little daughter said today that-- you know, she said, "Is Mr. Nixon going to be on?" I said, "Yes." She says, "I do hope that man finds work."

NARRATOR: Nixon found work as a Wall Street lawyer, determined to succeed at what he called "the fast track." Pat Nixon had never been happy with the constant demands of politics and welcomed the prospect of a more normal existence. "I hope we never move again," she told him when they settled in New York. But politics had been Nixon's whole life, all he had ever known. He soon told friends he would die of boredom if he stayed in private life.

9th NEWSCASTER: Here is a bulletin from CBS News. In Dallas, Texas, three shots were fired at President Kennedy's motorcade in downtown Dallas.

NARRATOR: To some, it seemed that Kennedy's assassination might open the way for Nixon in the next election, but sensing the mood of the country, Nixon concluded that Lyndon Johnson, the new President, would be unbeatable in 1964.

2nd REPORTER: Are you writing yourself off at this point as a political candidate, as a presidential candidate at any time?

Vice Pres. NIXON: Well I've made it clear that I am not a candidate for public office. I shall not become a candidate in this year, 1964, and I certainly have no plans to become a candidate in the future. I also want to make it clear at the same time, however, I'm not writing myself off as a political leader in the United States.

NARRATOR: As Nixon expected, President Johnson overwhelmed Republican Barry Goldwater in 1964 and the party lost disastrously in Congress. But in the ruins of that defeat, Nixon saw his way back to power. He worked the Republican congressional circuit tirelessly, traveled to 35 states, barnstormed for 105 candidates. And when the party made a dramatic comeback in 1966, there was hardly a Republican who didn't owe Nixon a favor.

LEONARD GARMENT, Law Partner: He was uncomfortable with all of the obligatory activities of politics. Those were the dues one paid in order to gain admission to the arena and he paid them. He flinched on occasion, but he paid them. He learned to do what he had to do.

Vice Pres. NIXON: [campaigning] Hey, how are you doing, boys?

VOTER: Good to see you. Good to see you.

Vice Pres. NIXON: Get this boy in now. You got to get him in.

VOTER: We're going to.

Vice Pres. NIXON: You know, this is your old district. You get him in now.

VOTER: We're going to get him in.

NARRATOR: Nixon promised his family a moratorium on politics in 1967, but immediately took off on a grueling tour of four continents. Traveling as a private citizen, the former Vice President could still command a crowd in the most remote reaches of the globe. His trips kept him in the news and strengthened his grasp of foreign policy. Once again, Richard Nixon was aiming for the presidency.

Mr. JOHN EHRLICHMAN, Nixon Campaign Staff: He had this absolutely core fire that he wanted to be President of the United States, I think for several reasons: probably to prove a lot of things to himself, but also because he sincerely wanted to take the country in a direction that he felt was the right direction.

NARRATOR: As Nixon officially announced his candidacy in February 1968, the events of that tumultuous year moved him closer to the office he had sought for so long. In Vietnam, Communist guerrillas fought their way to the very doorstep of the American embassy in Saigon. Never had the prospects for victory looked more bleak. At home, anger over the war tore the country apart and forced Lyndon Johnson to withdraw from the presidential race. Robert Kennedy was just beginning to emerge as the Democratic front runner when he was killed an assassin's bullet. Race riots following the murder of Martin Luther King turned many cities into battlegrounds. The country had not suffered such upheaval since the Civil War. Many American yearned for a leader who promised safety and stability.

In Miami Beach, safe from the crises that engulfed the country, the Nixon family watched as Republicans chose their candidate.

Vice Pres. NIXON: [at hotel] There. We worked for those. Ha ha.

WISCONSIN DELEGATION LEADER: [1968 Republican National Convention] When the strongest nation in the world can be tied down for four years in a war in Vietnam with no end in sight, when the nation with the greatest tradition of the rule of law is plagued by unprecedented lawlessness, when a nation that's been known for a century for equality of opportunity is torn by unprecedented racial violence, then it's time for new leadership for the United States of America.

NARRATOR: Republicans once again pinned their presidential hopes on Richard Nixon. To them and to many in the press, he seemed a "new Nixon," better prepared than the man who had lost in 1960. But the Democratic front runner, Hubert Humphrey, said he'd seen it all before.

Senator HUBERT HUMPHREY, Presidential Candidate: They started the renewal job in 1952, a "brand-new" Nixon. There was some reason for it, too. Then they had another renewal job in 1956. Then they had another renovation operation in 1960. Then, when he went to run for governor in California in 1962, they renewed him again. And then, in 1964, another touch-up. And now, I read about the "new Nixon" of 1968. Ladies and gentlemen, anybody that had his political face lifted so many times can't be very new.

NARRATOR: Boating in the Florida keys, Nixon was relaxed and confident. He was running far ahead of Humphrey in the polls and the Vietnam War was splintering the Democrats.

ANTI-WAR DELEGATES, 1968 Democratic National Convention: [chanting] We want peace now. We want peace now. We want peace now.

NARRATOR: At their convention in Chicago, the anti-war wing of the party pressed for an end to the bombing and a negotiated withdrawal of U.S. troops, but Humphrey stuck by President Johnson's policy.

Sen. HUMPHREY: [1968 Democratic National Convention] And I think that withdrawal would be totally unrealistic and would be a catastrophe.

NARRATOR: As the Democrats fought over Vietnam, Nixon avoided the issue, promising only that he would find "an honorable end" to the war. Along with millions of Americans, he watched on television as anti-war protests outside the convention hall exploded into violence. In the chaos, Nixon saw an opportunity. A few days later, he moved through the same streets in a motorcade. Four hundred thousand people turned out to cheer him. He chose the city which had seen open war among the Democrats to sound one of the central themes of his campaign.

Vice Pres. NIXON: [1968 campaign] This is a nation of laws and as Abraham Lincoln has said, "No one is above the law, no one is below the law," and we're going to enforce the law and Americans should remember that if we're going to have law and order.

NARRATOR: The emphasis on law and order appealed to millions of Americans. Nixon's television commercials hammered it home.

Vice Pres. NIXON: [television commercial] In recent years, crime in this country has grown nine times as fast as population. At the current rate, the crimes of violence in America will double by 1972. We cannot accept that kind of future for America. We owe it to the decent and law-abiding citizens of America to take the offensive against the criminal forces that threaten their peace and their security and to rebuild respect for law across this country. I pledge to you--

NARRATOR: To the Democrats, Nixon's call for law and order played to the worst in Americans.

Sen. HUMPHREY: But you can't vote your anger, you have to vote your hopes. You can't vote your hates, you have to vote your hopes.

The preamble to the Constitution doesn't just say "Double the rate of convictions," it doesn't just say, "Law and order," it says, "To ensure justice." And if Mr. Nixon hasn't read it, then I'll send him a copy.

NARRATOR: But Nixon had a feel for the issues that moved the middle American voter. They were the same issues that moved him. Blaming liberal Democrats for the upheaval in the country, he sought to rally a new Republican majority.

Vice Pres. NIXON: The new voice that is being heard across America today. It is not the voice of a single person, it's the voice of a majority of Americans who have not been the protesters, who have not been the shouters. The great majority finally have become angry, not angry with hate, but angry, my friends, because they love America and they don't like what has been happening to America for the last four years.

3rd REPORTER: You've just heard Richard Nixon refer to you, among all these people, as the "forgotten Americans." What do you think he's referring to?

MAN ON THE STREET: Well, I sort of think he's talking about the people that are paying the taxes, that are supporting the schools, the churches, the people that are-- they are sort of forgotten because everything's aimed at welfare and things like that.

NARRATOR: Nixon's call to the "forgotten Americans" appealed to a bread band of voters, mostly white middle class, hawkish, patriotic. It was a group that felt ignored and excluded in the upheavals of the 60s. And the strategy seemed to be working. Nixon held his strong lead into the fall.

Then, just before the election, President Johnson suddenly stopped the bombing of North Vietnam. Humphrey surged in the polls.

Sen. HUMPHREY: We're going to have the biggest election surprise that America's known in 20 years. We're going to win this election! Thank you very much.

NARRATOR: By election night, Nixon and Humphrey were dead even. Nixon prepared his family for the possibility of still another defeat.

WALTER CRONKITE, CBS News: We see that Nixon has closed a little bit in the last few tabulations there.

GENE BARRY, Actor, Humphrey Supporter: I think before the morning is out, Hubert Humphrey will be the next President of the United States.

Mr. Cronkite: And there have been no changes. None of those bit states have fallen yet, the ones we are waiting for.

NARRATOR: All night long, the lead shifted back and forth. The results weren't announced until 8:00 the next morning.

Mr. CRONKITE: With the 26 electoral votes in Illinois, Richard Nixon goes over the top with 287 electoral votes, he needed 270 to win and that seems to be the 1968 election.

COMMENTATOR: [at victory party] And he is beaming, Pat Nixon is beaming. One can't help but think back to 1960, when a tearful Pat Nixon was choking back the emotions. It was a totally different scene, of course, then. Here is possibly one of the most fantastic political comebacks in American history.

Pres. NIXON: I saw many signs in this campaign. Some of them were not friendly. Some were very friendly. But the one that touched me the most was one that I saw in Deshler, Ohio at the end of a long day of whistle-stopping. A teenager held up the sign, "Bring us together," and that will be the great objective of this Administration at the outset, to bring the American people together.

NARRATOR: Nixon spoke of unity, but his margin of victory had been extremely narrow. He had not reached out to blacks or the poor or opponents of the war. And a nation as badly divided as America in 1968 would not be easy to lead.

Peacemaker

NARRATOR: At age 56, after 22 years of political battle, Richard Nixon had become the most powerful man in the world. He envisioned nothing less than a new world order with himself as its architect.

Pres. NIXON: [Inaugural Address] The greatest honor history can bestow is the title of "peacemaker." This honor now beckons America.

If we succeed, generations to come will say of us now living that we mastered our moment, that we helped make the world safe for mankind. This is our summons to greatness.

Mr. ELLIOTT RICHARDSON, Nixon Cabinet Member: And there's no question at all that Nixon aspired to greatness. He would talk constantly about he "generation of peace" that he hoped to contribute to building, that would indeed be his bequest to the United States and the world.

NARRATOR: As Nixon took power, he assembled a staff that would leave him free to carry out his ambitious plans and whose loyalty had already been demonstrated.

H.R. HALDEMAN, White House Chief of Staff: The White House staff, as it evolves, I think you will find will be smaller than it's been in the past.

NARRATOR: H.R. Haldeman, a former advertising executive who had been at Nixon's side since 1956, was made Chief of Staff. He was proud, he once said, to be Richard Nixon's "son of a bitch." John Ehrlichman, a lawyer and top aide during the campaign, would handle much of domestic policy.

Together, he and Haldeman would tightly control access to the President.

Those whom they excluded called them "the Berlin Wall." Behind that wall, Nixon could focus on his main interest, foreign policy, bypassing the State Department to work closely with his National Security Adviser, Henry Kissinger.

Pres. NIXON: Dr. Kissinger is perhaps one of the major scholars in America in the world today in this area. He has never yet had a full-time government assignment and he will bring to this responsibility a fresh approach.

Mr. ROGER MORRIS, Kissinger Aide and Nixon Biographer: They organized the government to concentrate power in the hands of these two men in the White House. And it's not accidental that he appoints an old friend, but a decidedly weak practitioner in Bill Rogers in the Department of State or essential a Wisconsin Dells politician, Melvin Laird, as Secretary of Defense. There are no strong figures in his cabinet and there are no strong foreign policy figures anywhere in the higher echelons of the government.

It is to be Richard Nixon's foreign policy and it is to be carried out with sophistication and some subtlety by Henry Kissinger.

NARRATOR: Looming over the new Administration was the war in Vietnam. American troops had been fighting for four years on behalf of South Vietnam against the Soviet-backed Communist forces of the North. The war had already taken the lives of 30,000 Americans and over a million Vietnamese.

And destroyed one President. Nixon was determined not to let it destroy him. Even before his inauguration, Nixon had Kissinger began secret contacts with the North Vietnamese in an attempt to move the stalled Paris peace talks forward and soon, the two men developed a strategy they hoped would get the U.S. out of the war without abandoning America's ally, South Vietnam.

Pres. NIXON: We have adopted a plan which we have worked out in cooperation with the South Vietnamese for the complete withdrawal of all U.S. combat ground forces and their replacement by South Vietnamese forces on an orderly, scheduled timetable. This withdrawal will be made form strength.

NARRATOR: Confident that this policy would end America's involvement in Southeast Asia by the end of 1970, Nixon and Kissinger turned their attention to global strategy, reshaping America's entire relationship with the Communist world.

Mr. ROGER MORRIS, Nixon Biographer: And they both began, in 1969-1970, with a notion that only lately has become fashionable in Washington and that is that the post-war is really over, that the cold war ought to be a thing of the past.

They are, in that sense, almost 20 years ahead of their time.

NARRATOR: Recognizing that the Soviet Union had nearly caught up to the U.S. in nuclear strength, Nixon and Kissinger dispatched a team of negotiators to work out a treaty with the Soviets. For the first time in the history of the nuclear age, the two superpowers sat down to discuss setting limits on nuclear weapons. At the same time, they began secret contacts with the other great Communist power, China. There were few more forbidding and isolated places in the world in 1969, but Nixon believed that China, with its vast population and growing nuclear arsenal, would soon be too powerful to ignore.

Mr. ROGER MORRIS, Nixon Biographer: Here, for the first time in the 20th century, we have two men at the very pinnacle of the American government who have some clear notion, not only of what the world is doing out there, what's happening in the world, but of where they want the United States to fit in. We are not a nation that practices its foreign policy by design, for the most part and Nixon and Kissinger are an exception to that rule.

NARRATOR: In the summer of 1969, Nixon announced the first American troop withdrawals from Vietnam. Arms control, China, Southeast Asia. He seemed to be moving steadily toward becoming a peacemaker.

Mr. Nixon's War

GEORGE C. SCOTT, Actor: [in "Patton"] Ten-hut!

NARRATOR: Richard Nixon loved the movie Patton and watched it again and again in the White House. General George Patton was a man of action, contemptuous of his critics, uncompromising, determined to win at all costs.

Mr. SCOTT: Be seated. Now, I want you to remember Americans love a winner and will not tolerate a loser. Americans play to win all the time and I wouldn't give a hoot in hell for a man who lost and laughed. That's why Americans have never lost and will never lose a war because the very thought of losing is hateful to Americans.

NARRATOR: Richard Nixon was determined not to be the first American President to lose a war. He might simply have brought the troops home and blamed Vietnam on the Democrats, but Nixon, like many of his contemporaries in both parties, believed that abandoning South Vietnam to the Communists would be a defeat that invited further aggression, a sign that America could no longer be counted on by her allies. Despite mounting pressure for immediate withdrawal, he stuck to his gradual course, while trying to negotiate what he called "an honorable end" to the war. But the months dragged on. Casualties mounted and Nixon's policy seemed only to prolong America's agony.

DANIEL PATRICK MOYNIHAN, Assistant to the President for Urban Affairs: And I said, with respect to Vietnam, I said, "The war in Vietnam is lost and the sooner you get out, the better we will be." It was lost, but they-- he, for some reason, kept at it. It wasn't his war and it seemed to me that just him handling a presidency, you stick around with a war for two years and it's your war. And it became his war. And in the end, half the country seemed to think he started it.

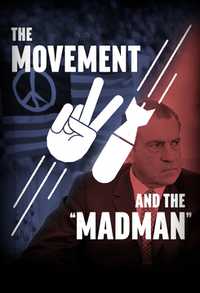

NARRATOR: In October 1969, the largest anti-war demonstrations in the nation's history, collectively known as "the moratorium," were held in cities all over the country. Critics of the war had waited nine months for Nixon to make good his pledge to end the conflict, but now, the honeymoon was over.

Pres. NIXON: I understand that there has been and continues to be opposition to the war in Vietnam on the campuses and also in the nation. As far as this kind of activity is concerned, we expect it. However, under no circumstances will I be affected whatever by it.

Mr. JOHN EHRLICHMAN, Nixon Campaign Staff: The moratorium itself was seen by Richard Nixon as 200,000 people out there on the Mall, protesting his foreign policy while at the same time, the polls were showing that 58-59 percent of the American people supported him in his foreign policy. And he would look out the window and he would say, "I simply cannot permit foreign policy to be made in the streets of Washington."

DICK GREGORY, Comedian, Vietnam War Protester: The President of the United States said nothing you young kids would do would have any effect on him. Well, I suggest to the President of the United States, if he want [sic] to know how much effect you youngsters can have on the President, he should make one long-distance phone call to the LBJ Ranch and ask that boy how much effect you can have.

NARRATOR: The fate of Lyndon Johnson did haunt Richard Nixon. He felt he had to demonstrate that most Americans still supported him and that it would not benefit Hanoi to stall peace negotiations. "Don't get rattled.

Don't waver. Don't react," he told himself as he went to work on a speech to respond to the protests. Insisting on writing it himself, he distinguished his supporters, "the forgotten Americans," from the vocal minority in the streets, with a new catch phrase.

Pres. NIXON: [November 3, 1969] To you, the great silent majority of my fellow Americans, I ask for your support, for the more divided we are at home, the less likely the enemy is to negotiate at Paris.

Let us be united for peace. Let us also be united against defeat because let us understand: North Vietnam cannot defeat or humiliate the United States. Only Americans can do that.

NARRATOR:It was the most effective speech of Nixon's presidency. Eighty thousand telegrams and letters arrived at the White House. Nearly all supported him. His approval rating soared. But the war continued and with it, the protests.

Mr. ROGER MORRIS, Nixon Biographer: I think Richard Nixon came to office expecting, if not a quick fix in Vietnam, expecting a kind of responsiveness in the war. He had made certain speeches, he had offered certain gestures, he had proffered, both secretly and publicly, what he thought were promising initiatives in negotiations. None of that had yielded anything. There was a palpable sense of frustration in the Administration about how long this war was going to drag on. Out of the Oval Office began to flood memoranda that were stream-of-consciousness renditions of the President's fears and ambitions in Southeast Asia. His image of this whole contest as a kind of challenge being issued not only by the parties on the ground -- by the Cambodian rebels and the North Vietnamese and the Vietcong -- but ultimately by more formidable and distant forces -- the Soviet Union, by China, by his enemies -- testing him, measuring his mettle as a man and as a leader.

Mr. JOHN EHRLICHMAN, Nixon Campaign Staff: He took me aside and he said, "I'm going to be out of the play for ten days here. I won't be able to handle any domestic decisions for ten days. So come back this afternoon and tell me all the things that need to be decided for the next ten days and then I won't be able to see you because I'm going to be focusing on this business of Vietnam. We're going to try and bring it to a head."

NARRATOR: At the Pentagon, Defense Secretary Laird waited for the President. After days of tense deliberation, Nixon was about to announce an attack on enemy sanctuaries across the Vietnam border in Cambodia and he would do so over the objections of many White House advisers.

Mr. ROGER MORRIS, Nixon Biographer: We thought the invasion was a bad idea and that it was one more round of escalation on the pattern, on an old pattern in Vietnam which would cost lives and national treasure and really only prolong the suffering and do nothing to affect the larger outcome of the war.

NARRATOR: But the military and Kissinger recommended the action and Nixon wanted to go ahead. He was convinced that destroying the North Vietnamese hiding places in Cambodia would relieve Communist pressure on the South. And he wanted to take some dramatic action to demonstrate that neither Hanoi nor the anti-war movement could intimidate the United States or its President.

Pres. NIXON: [April 30, 1970] If, when the chips are down, the world's most powerful nation, the United States of America, acts like a pitiful, helpless giant, the forces of totalitarianism and anarchy will threaten free nations and free institutions throughout the world. It is not our power, but our will and character that is being tested tonight.

NARRATOR: As Nixon spoke, American troops moved into Cambodia. His critics were outraged. The President who had promised to end the war seemed to be widening it, moving into a country perceived as neutral. Three members of Kissinger's staff, including Roger Morris, resigned in protest.

Nixon was unmoved.

Pres. NIXON: I would rather be a one-term President and do what I believed was right than to be a two-term President at the cost of seeing American become a second-rate power and to see this nation accept the first defeat in its proud 190-year history.

NARRATOR: Early the next morning, Nixon went to the Pentagon for a firsthand briefing. The military was reporting success. Nixon was encouraged and praised American soldiers fighting in the jungles of Southeast Asia. The wife of one of those soldiers reached out to shake his hand. Nixon drew a sharp contrast between the troops in Vietnam and the student protesters at home.

Pres. NIXON: You know, you see these bums, you know, blowing up the campuses. Listen, the boys that are on the college campuses today are the luckiest people in the world and here they are, burning up the books, I mean, storming around about this issue, I mean, you name it. Get rid of the war, there'll be another one.

NARRATOR: Nixon's remarks further infuriated students already protesting over Cambodia. After three tense days of demonstrations at Kent State University in Ohio, nervous National Guardsmen opened fire. Four students were killed. "My child was not a bum," said the father of one dead girl. American campuses exploded. Hundreds of colleges and universities closed down. Governors in 16 states called out the police and National Guard. Nixon's supporters took to the streets as well. At New York's City Hall, construction workers struggled to raise the flag which the mayor had lowered to honor the dead at Kent State. Nixon's move into Cambodia and his dividing of Americans into bums and heroes had set off a national firestorm.

Angry protesters returned to Washington. As tensions rose, the Secret Service ringed the White House with a barricade of buses.

CHARLES COLSON, Special Counsel to the President: It was like living in a bunker in the White House. I mean, we'd look out in the streets and see thousands of people protesting. You literally were afraid for your life. There were times when I can remember saying, "I can't believe this is the United States of America, a free country," and here we are in the White House with barricades up and buses around the White House and tear gas going off and thousands, hundreds of thousands of protesters out in the streets and troops sitting here.

NARRATOR: An embattled Nixon faced the press, as anti-war demonstrators continued to flock to Washington.

HERB KAPLOW, Reporter: [White House press conference] What do you think the students are trying to say in these demonstrations?

Pres. NIXON: They're trying to say that they want peace. They're trying to say that they want to stop the killing. They're trying to say that they want to end the draft. They're trying to say that we ought to get out of Vietnam. I agree with everything that they're trying to accomplish. I believe, however, that the decisions that I have made will serve that purpose.

NARRATOR: That night, protesters circled the White House with chants and candles. Inside, a sleepless Nixon made more than 40 phone calls to friends and supporters around the country. Near dawn, he called for a car and asked to be driven to the Lincoln Memorial, where protesters had gathered. White House aide Egil Krogh followed him.

EGIL KROGH Jr., White House Aide: It was-- I guess it was almost a surreal atmosphere. It was almost like dreamlike, "Is this really happening?" Walking up the stairs of the Lincoln Memorial and there was the President, sort of standing in the middle of a group of young people who were wearing combat fatigues with peace symbols and bandannas and all of the clothing of the 60s and the 70s and trying very hard to communicate to them.

LAUREE MOSS, Student Protester: I think I said, "Well, what are you going to do about the Kent State killings? What are you going to do about the war?" He said, "I'm really not here to talk about that right now. We're trying to handle things." So it was a one-way, you know, conversation or a one-way street. Yeah, because he was there, trying to be very conversational and casual, and we were there, outraged and angry and scared.

Mr. EGIL KROGH Jr., White House Aide: One student basically told him, he said, "I hope that you realize that we are willing to die for what we believe in." And I think-- as I recall, the President's response was, "Well, I understand that, but we're trying to build a world where people will not have to die for what they believe in."

NARRATOR: When he appeared as the guest of honor at a Billy Graham crusade in Tennessee, Nixon had been in office 16 months. A majority of Americans still backed his Vietnam policy, but the furor over Cambodia had deepened the divisions Nixon had promised to mend. Even here, surrounded by thousands who supported him, the President could not escape the ceaseless storm of protest.

Pres. NIXON: [Billy Graham crusade] And if we're going to bring people together, as we must bring them together, if we're going to have peace in the world, if our young people are going to have a fulfillment beyond simply those material things, they must turn to those great spiritual sources that have made America the great country that it is. I'm proud to be here and I'm very proud to have your warm reception. Thank you very much.

NARRATOR: Throughout the next year, Nixon continued to try to rally his supporters, while denouncing his opponents, calling some among the protesters "thugs and hoodlums," blaming his critics in Congress and the press for failing to support the war. All U.S. troops left Cambodia by the end of June, as Nixon had promised. He insisted that the military action which had caused such turmoil had eased the pressure on the troops in Vietnam. Withdrawals continued on schedule, but more American lives had been lost. There was no break-through in the peace talks. And in the White House, an increasingly frustrated and suspicious Nixon urged intensified surveillance of the anti-war movement. He grew distrustful even of his closest advisers and installed hidden microphones in his own office, in part so that his aides could not later claim to have disagreed with his decisions. But the taping system would eventually trap the President himself.

Enemies

NARRATOR: On June 12, 1971, the White House staff prepared for a wedding in the Rose Garden. The President's elder daughter, Tricia, was to be married to a young law student, Edward Cox. Rain threatened the ceremony and Nixon spent much of the afternoon on the phone to Air Force weathermen.

Finally, there was a prediction of a 15-minute break in the weather.

Pres. NIXON: I got to get dressed. You know, I got to get-- let's see, all my things, my hair done.

ART LINKLETTER, TV Personality: [at wedding reception] I saw the President more relaxed and more happy and more like a typical American father than I've seen him in a long, long time.

5th REPORTER: He looked like he was doing a great job out on the dance floor, too.

Mr. LINKLETTER: Yes. And he doesn't dance all that often, you know.

NARRATOR: "It was a day that all of us will remember," Nixon later wrote, "because we were beautifully and simply happy." The next morning, Nixon picked up The New York Times. In the left corner was an account of Tricia's wedding. Across the page was another headline, the first installment of what came to be called the "Pentagon Papers," a secret Defense Department study which revealed past government deception about the war in Vietnam. Daniel Ellsberg, a former Defense Department employee who had turned against the war, had given the top secret documents to the press.

DANIEL ELLSBERG, former Defense Department Employee: I can no longer cooperate in concealing this information from the American public.