Narrator: Late in 1865, a fierce blizzard swept across the plains of Indiana, into western Ohio. Phoebe Anne Moses, the fifth surviving child in a Quaker farming family, waited for her father to come home from the mill, 15 miles away. It was midnight when Jacob Moses finally returned. His hands were frozen solid, his speech gone. He never recovered. Jacob died in March. Phoebe Anne -- Annie -- was not yet six years old. The family soon lost the farm. Bills piled up. They were destitute.

To ease the burden, Annie's mother sent her to live at the county poor farm. Soon she was hired out to work as a live-in helper for a family in a neighboring county.

Virginia Scharff, Historian: Everyone thought that this would be an improvement, but it turned out to be absolutely nightmarish situation.

She never mentioned their name again the rest of her life. She referred to them as the "wolves."

They locked her in closets. They worked her half to death.

Shirl Kasper, Biographer: One day the farmer's wife, the wolf, Mrs. Wolf, throws her out in the snow, because she fell asleep while she's doing some darning.

Annie Oakley: Suddenly the "She-Wolf" struck me across the ears, threw me out into the deep snow and locked the door. I had no shoes on. I was slowly freezing to death. So I got down on my knees, looked toward God's clear sky, and tried to pray. But my lips were frozen stiff and there was no sound.

Shirl Kasper, Biographer: If she was sexually abused, we don't know. She certainly was physically abused. She talks about welts on her back. She talks about being a slave.

I think Annie's experience with the wolves leaves such a deep impression on her -- maybe it's some kind of shame.

And I wonder if that shame is so deep in Annie that it influences the rest of her life.

Narrator: Annie endured two years with "the wolves," forced to help her own family survive by being one less mouth to feed.

Then one day in 1872, 12-year-old Annie Moses could bear it no more. She ran away, slipped into a crowded railroad car, and made her way back to Greenville.

Her mother was still unable to support another child.

Annie went back to the poor farm, where she earned her keep working as a seamstress. At the age of 15 she finally returned to her mother. Susan Moses had remarried, but the family was still desperately poor, and a mortgage loomed over their heads.

Instead of going to school, Annie taught herself to shoot. With her father's old cap-and-ball rifle, she headed for the woods to hunt.

Soon she was selling hampers of quail to Katzenburger's General Store in Greenville. Young Annie was now the family breadwinner, earning a living with her gun.

Mary Zeiss Stange, Professor of Women's Studies: She was a market hunter and turning a very nice profit. Certainly not something that was at all appropriate for a woman to be doing in that time and place.

Narrator: Eventually she saved up enough money to pay off the $200 mortgage on the family farm. And her prowess with a shotgun was becoming known around Greenville.

In the 1870s, shooting well was an important skill for a man, and shooting contests were a favorite spectator sport.

Sharpshooters traveled the country, betting on their ability to perform feats of marksmanship and challenging all comers.

R. L. Wilson, Firearms Historian: Shooting was of such immense popularity that there were professionals.

Doc Carver, Evil Spirit of the Plains is what he was called. Captain Bogardus, who would eventually have four sons who would travel with him. And people were flocking to see shooters like this.

Narrator: One such shooter was Frank Butler. An Irish immigrant in his mid-20s, Butler was just starting to make a name for himself on the variety stage. He was passing through Southern Ohio one fall -- claiming he could outshoot anyone around.

Shirl Kasper, Biographer: Frank is staying in a hotel in Cincinnati and he starts talking with a bunch of farmers. The farmers say, "Hey we have someone in our county who's a really good shot and we're going to bet 100 bucks that this person can beat you."

Narrator: Butler laughed -- but he needed the money.

The match was on.

R. L. Wilson, Firearms Historian: Frank Butler, this already professional shootist shows up for this match with hundreds of people watching, and who is it that comes as his opponent but a 15-year-old girl who was only five feet tall and weighed a hundred pounds?

Narrator: "The moment she appeared," Butler recalled, "I was taken off guard."

Annie's first shot was a hit. Both shooters hit 24 birds in a row. Then Butler missed.

"I stopped for an instant," Annie remembered. "I knew I would win." And she did.

The loser was instantly smitten. He offered Annie tickets to his next show.

Shirl Kasper, Biographer: He must have seemed to her, like, a man of the world. That's the only way I can think of it. You know, here she's lived her whole life in the Ohio woods, and here's this man who's with the circus. He's been on the variety stage.

Virginia Scharff, Historian: It was chemistry. He made himself appear safe to her. He clearly admired her. He sparked and courted her as few of us have ever been sparked or courted and everyone of us would like to be by someone, and she was lucky to find him and I think he knew he was lucky to find her.

Narrator: Frank Butler was Annie's ticket out of Greenville. They soon married.

For the next six years, while Butler and his new shooting partner John Graham performed on the variety circuit, Annie stayed in the background. That was about to change.

Butler and Graham were playing a theater in Springfield, Ohio, when John Graham suddenly fell ill. Annie filled in, holding the targets.

That night Frank kept missing -- until a jeering spectator shouted, "Let the girl shoot!"

Frank obliged.

Annie hit the targets every time -- much to the delight of the raucous crowd.

"Butler and Graham" soon ceased to be.

Mrs. Butler took a stage name, borrowed from her paternal grandmother -- Annie Oakley.

When the shooting team of "Butler and Oakley" hit the road, traveling entertainment was in its heyday.

Circuses, theatre companies and vaudeville acts traveled the country, playing venues from outdoor arenas to smoky saloons.

For Annie and Frank, it was an exhausting life of noisy train rides, seedy hotels, and one-night stands. Their shooting act might be sandwiched in between a bawdy songstress and a scantily-clad acrobat.

Don B. Wilmeth, Theatre Historian: Variety was a largely male-oriented form of entertainment. There was a good deal of double entendre in comedy, there were suggestive lyrics in songs, and there was a good deal of semi-nudity. The acts could be a tad salacious.

Narrator: It was the Victorian Age. Annie Oakley, the Quaker girl from Ohio, feared being thought a loose woman. She resolved to set herself apart -- both in manner and in dress.

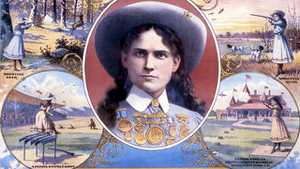

She began wearing an outfit that completely covered her body -- a calf-length skirt, long sleeves and leggings. It became her trademark.

Joy Kasson, Historian: She made her own costumes. That was very important to her -- was part of her desire to control her self-presentation. She could move easily in them, and yet she looked ... she looked respectable. She looked childlike.

Narrator: Frank soon realized that Annie was the main attraction of Butler and Oakley. In a remarkable reversal of 19th century roles, Frank Butler became Annie Oakley's assistant.

Virginia Scharff, Historian: I think Frank Butler understood that she had a kind of star quality that he didn't want to overshadow, and Frank Butler didn't have a problem with that. I think he adored her. I think he also was a savvy businessman who understood that she was pretty, she was ladylike, she was petite, she would do what needed to be done to make that rise to the top. And he didn't want to get in her way. As a matter of fact, he understood that for the two of them, the best thing possible was to let her take the lead.

In 1884 Butler and Oakley landed a 40-week job with Sells Brothers Circus, one of the biggest traveling shows in the country.

Finally, they had steady work with a clean, family-oriented show. But circus life was hard and the pay unreliable.

When the season ended in New Orleans that December, it looked as if Frank and Annie would have to go back to a life of one-night stands and unsavory characters.

Shirl Kasper, Biographer: The circus season is ending the very week that Buffalo Bill's Wild West comes to New Orleans and it's like, "Wow, the circus is ending. We need a job." So they ask Cody if they can come on with his show.

To Annie, it seemed like a dream job -- Buffalo Bill Cody's show was the first of its kind -- a re-creation of the West, featuring the finest performers in the country. But Cody didn't need Annie Oakley -- he already had a star shooter.

Shirl Kasper, Biographer: He has Captain Bogardus, who's like this really famous shot, champion of the world. He's very well known. And so Cody turns them down.

Paul Fees, Historian: It's not that she was a woman. There were, after all, already Indian women in the show. Cody had worked with women in the theater. There were just not the dramatic elements in the show yet that could make use of a woman like Annie Oakley.

Narrator: The Butlers reluctantly headed north, back to the variety circuit. Then, fate intervened.

Buffalo Bill's steamer sank on the Mississippi River.

Captain Bogardus lost all his shooting equipment and quit the show.

Frank and Annie promptly wired Cody, asking for an audition. Buffalo Bill was skeptical -- the girl was asking for too much money. And Cody -- a champion sharpshooter himself -- didn't think such a tiny woman would have the endurance to perform night after night.

Still, he agreed to a try-out.

As she was practicing in an empty stadium, Annie noticed a man in a fancy hat standing by the grandstand, staring at her.

Suddenly he ran over, shouting "Fine! Wonderful! Have you got some photographs with your gun?"

The dapper gentleman was Cody's business manager, Nate Salsbury. He hired Oakley on the spot.

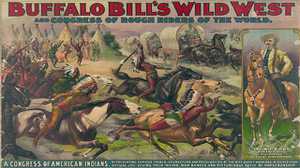

Buffalo Bill's Wild West show was a lavish spectacle -- part melodrama ... part circus ... part rodeo.

It offered a taste of life on the old frontier -- to an America that was rapidly industrializing.

In the crowded urban centers of the East, people flocked to Buffalo Bill's show -- eager for a glimpse of the Wild West.

Paul Fees, Historian: The whole world was fascinated with the West, and as it was becoming settled, those elements that were seen as the foundation of America's uniqueness -- the rugged individualism, and the adventure, and the conflict with Indians and with and with buffalo, and all of those reckless parts of America's past -- seemed to be coming to an end. Buffalo Bill was a representative, a living representative of that story, of that adventure. And it's that adventure that he put into his Wild West Show.

Audiences saw the real stagecoach, they saw real soldiers, they saw real Indians and cowboys.

Joy Kasson, Historian: There were horses -- there were steer -- there were live buffalo.

Narrator: It was into this roiling microcosm of the Wild West that Annie Oakley, the little girl from Ohio, first stepped in April 1885.

Cody placed her low on the bill, but she soon became an audience favorite.

Shirl Kasper, Biographer: She tripped into the arena. She didn't walk in. She blew kisses. She waved. She was like animated, alive... like this sweet kind of person, but with this big bang gun.

Shirl Kasper, Biographer: She starts off slow -- one ball, two balls.

R. L. Wilson, Firearms Historian: Glass balls which, when they're hit, they explode and feathers fly out.

Paul Fees, Historian: Frank would toss up one, and then two at a time, and then three at a time.

And then Annie Oakley would toss them up herself. She'd toss two or three or four target balls in the air, grab a shotgun, shoot two, grab another, shoot two more.

R. L. Wilson, Firearms Historian: And she could hit all three before any one of them would reach the ground. And then she'd go to six.

Shirl Kasper, Biographer: Her act gets faster and faster and faster and faster, until, you know, it's just like boom, boom, things are just being broken all around.

R. L. Wilson, Firearms Historian: She could shoot with her left hand, with her right hand.

Shirl Kasper, Biographer: She like turns her gun upside down, or sideways, or sighting in a mirror.

R. L. Wilson, Firearms Historian: One of her favorite tricks was to have Frank hold a playing card up, and she could either shoot through the heart when it was flat against her, or, if it was held sideways, she could split the card it two, which is a pretty amazing shot.

Occasionally she'd miss a shot on purpose, and then she'd kind of pout, and this was part of the act, because she -- she could always hit the target. She was somebody who never missed.

Shirl Kasper, Biographer: I think it's an innate skill. She said, you know, "Nobody ever taught me to shoot." I think it was just -- "A love of the gun was just born in me."

R. L. Wilson, Firearms Historian: It was an instinct and a skill and an ability that only persons who have phenomenal vision, have a wonderful sense of timing, who have hand-eye coordination, who have good balance and were really very athletic, because a really good shot has to be a really good athlete.

Narrator: Once Annie's act started getting rave reviews, Cody moved her up the bill, right after the opening procession.

That season, 150,000 people in 40 cities across America saw something entirely new -- a woman who could shoot as well as any man while conveying a youthful innocence, that -- whether Annie realized it or not -- was sexy. It was the stuff of stardom.

Elliot West, Historian: She was this really, remarkable, remarkable shot. But what makes her especially interesting is that she was able to combine that with an image, with a kind of vision of American womanhood that was provocative, but what many people felt comfortable with.

Don B. Wilmeth, Theatre Historian: I think what makes her unusual is the fact that she could project a kind of demure, lady-like, often almost a little girl person and at the same time be very sexual, very attractive physically.

Annie Oakley's celebrity grew when the Wild West spent the summer of 1886 in an arena on Staten Island.

Half a million people sailed past the new Statue of Liberty, then rode on special trains straight to the Wild West. It was the most popular attraction ever seen in New York and Annie was now becoming as famous as Buffalo Bill himself.

Frank became Annie's press agent, playing on the deep fascination Easterners had with the Old West. He advertised his Ohio-born wife as "The Girl of the Western Plains."

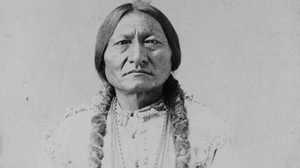

And he never tired of telling the story of the night Chief Sitting Bull, the old Sioux warrior, asked if he could adopt Annie -- after watching her shoot the ace of hearts out of a card at 30 paces.

Donald Fixico, Historian: When Sitting Bull first saw that she had these amazing abilities, you know, to handle a rifle, and her keen eye sight, then obviously she had some endowed power of some sort, that he recognized immediately. When Indian people look at such individuals that have been empowered like that, then we have the greatest respect.

Narrator: Sitting Bull christened his new daughter "Watanya Cecilia" -- "Little Sure Shot."

For a time he toured with Annie in Buffalo Bill's show, but the great chief soon left, saying he had grown sick of "the noises and the multitudes of men."

When Buffalo Bill's Wild West opened in Madison Square Garden in the fall of 1886, "Little Sure Shot" became the darling of Manhattan. She performed before 6,000 people, many in evening dress.

The mistreated, half-starved little girl from Ohio had become an icon of the American West.

Virginia Scharff, Historian: There was probably never a woman in the history of the United States who was better equipped to take up the challenge of creating a legend, creating a myth of the western woman and then embodying that myth with the kind of lady-like demeanor that would make her acceptable, it is a remarkable creation in American legend.

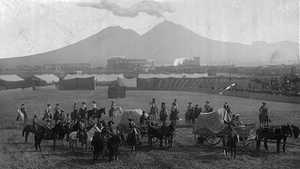

Narrator: In March 1887, Cody's Wild West troupe sailed from New York harbor, bound for London, to perform at Queen Victoria's Golden Jubilee.

Their ship was a veritable Noah's ark. The hold was packed with horses, buffalo, elk, and mules. Dozens of Native Americans huddled together, bracing for the first ocean voyage of their lives. California.

Clustered in the bow were Buffalo Bill, Annie and Frank -- but also Cody's new discovery -- 15-year-old Lillian Smith, a sharp-shooting sensation from California.

R. L. Wilson, Firearms Historian: Lillian Smith was an expert with a rifle, so much so that Cody himself had said he would pay $10,000 to anybody who beat Lillian Smith at rifle shooting.

Narrator: Even before they reached London, Lillian had been bragging -- "now that I'm with the Wild West," she declared, "Annie Oakley is done for."

R. L. Wilson, Firearms Historian: Lillian Smith tended to speak very coarsely and she was kind of rakish, she liked to hang around with the cowboys. And she had this bodice that said "Champion Rifle Shot of the World."

Narrator: This was not what Annie Oakley wanted to see just as her own star was on the rise.

Shirl Kasper, Biographer: Lillian Smith really shows how competitive Annie is. She's worried because Lillian's 15 years old. Annie is 26 now. Suddenly when you start reading the press releases, Annie becomes younger than she has been she now starts telling people she's born in 1866. Now she's 20 and she can compete a little easier with this new girl in the Wild West Show. She's practical. She does what she needs to survive.

Narrator: On May 9, 1887, when the Wild West show opened in London, Oakley and Smith were given equal billing.

Ten thousand eager spectators clamored to get in. The crush, and fight, and struggle to reach the gates... was something terrific," reported The London Evening News.

In attendance were leading British intellectuals, such as playwright Oscar Wilde, and many of the crowned heads of Europe.

Elliot West, Historian: The English were fascinated by America as a place where you could escape the traps of the modern industrial world. They saw America as a place of wide-open spaces, a place of the free individual in the wilderness.

And I think Cody's Wild West show and Annie Oakley herself spoke to that mixed appeal of America to the English.

Mary Zeiss Stange, Professor of Women's Studies: Annie particularly was a figure that Europeans welcomed, because on the one hand, she represented the wild western girl, that image that she had so carefully created and cultivated. But at the same time she was a Victorian woman who was there, after all, to meet the woman who created the Victorian era.

Narrator: In June, Queen Victoria herself came out to watch the show.

After the performance, her Majesty beckoned Annie and Lillian to approach the royal box. Lillian seized the moment, showing off her Winchester repeating rifle to the queen -- much to Annie's chagrin.

Shirl Kasper, Biographer: So Annie has some very severe competition. And it's not really with somebody that she respects. Annie says, you know, "Oh Lillian, her ample figure, her poor grammar... People would see the truth of her eventually." It shows just how much dislike there was between them.

Narrator: The most important shooting event in England was the annual rifle competition at Wimbledon, and the big-name American shooters were invited to compete.

Lillian Smith was the first to arrive. She shot poorly and left in a huff. The next day Annie Oakley appeared.

Shirl Kasper, Biographer: Annie does great. And she does it with a rifle. And Lillian's supposed to be the rifle expert. Annie's the shotgun shooter. So she has upstaged Lillian Smith, kind of beaten her at her own game. Annie becomes the toast of London, some papers even said she was more popular than Cody.

Narrator: Buffalo Bill never showed up at Wimbledon. "The gallant colonel," a London newspaper wrote, "was not the champion of his own show."

Another paper compared his marksmanship unfavorably with Annie's. Relations between Annie and Buffalo Bill became strained, even as the rivalry between and Annie and Lillian heated up.

A friend of Lillian's published a letter in a major American sporting periodical claiming that Lillian Smith was the toast of London while Annie Oakley had been forgotten.

Shirl Kasper, Biographer: And it's not true. You can imagine how Annie must feel about this. There's a huge rift behind the scenes in the Wild West and the press gets a hold of this.

Narrator: Frank Butler and Nate Salsbury responded with letters of their own, defending Annie's reputation.

Buffalo Bill Cody -- said nothing at all.

Shirl Kasper, Biographer: So who is he siding with, or why is he not sticking up for Annie? What's going on, that he -- that he's not talking? And I think there's a mention that Annie at some point says she has to kind of cut back on a few of her stunts in the Wild West arena because she's upstaging Cody. So there's probably some kind of jealousy all over the place.

Narrator: In late October, The London Evening News printed a stunning announcement -- Annie Oakley would "sever her connection with the Wild West voluntarily" following their final London performance that very evening.

After two and-a-half years in the bright spotlight of the Wild West Show -- at the very height of her popularity and earning power -- Annie Oakley left Buffalo Bill.

Her only public comment on the matter was a cryptic statement published years later -- "The reasons for so doing," she wrote, "take too long to tell."

In the spring of 1888 the Butlers took their act to the vaudeville stage.

But the times were changing. Singers, dancers, and comedians were what audiences now wanted to see -- not sharpshooters.

Annie worked briefly for other Wild West shows, but heard that Nate Salsbury was threatening to sue any company that hired her.

Shirl Kasper, Biographer: She has a really tough year after she leaves the Wild West. She kind of darts around. She goes and works for a circus. She goes in this terrible play, Deadwood Dick -- it's very irreputable. She says, "I'm amazed no one threw carrots at us."

Narrator: The show closed after a month, when the manager pocketed the receipts and skipped town.

Then in February 1889, much to Annie's surprise, Nate Salsbury came to call. Buffalo Bill was planning a trip to Paris that spring and wanted her back.

Shirl Kasper, Biographer: They needed her. They needed her more than they thought they needed her. And so whatever rift there was, is mended. And interestingly, Lillian Smith does not go to Paris. I mean, we don't know, but it would make sense that maybe, that was part of the bargain. "I'll come back if Lillian goes."

Narrator: Over 30 million people came to the Paris Exposition of 1889. Within sight of the new Eiffel tower, Buffalo Bill's Wild West played to overflow crowds night after night.

Annie Oakley was soon the talk of Paris. The French President offered "la belle Américaine" a commission in the army. The king of Senegal tried to buy her for 100,000 francs -- "to destroy the vicious lions who devastate my country's villages," he said.

Stories describing fictitious events from her past were splashed across newspapers all over Europe and America.

A dime novel described Annie's thrilling, if completely fictional, childhood in Kansas.

Shirl Kasper, Biographer: Totally Wild West -- she kills the bad guy, Darkey Morrow, with one shot. She kills a bear. She hits a panther through the eye. She saves the train from the train robber. She wrestles this wolf, and the wolf is biting her but she's so brave, she doesn't even cry out. They're turning Annie into a legend.

Narrator: Oakley's legend continued to grow, as she toured Europe with Cody for the next three years. It was said she saved the life of the prince of Bavaria -- throwing him to safety as he was about to be trampled by a bucking bronco.

Prince Wilhelm of Prussia was so impressed by Annie's skill that he insisted on participating in her act. He lit a cigarette -- from 30 paces, Annie shot it away.

"If my aim had been poorer," she later said, "I might have averted the Great War."

Or so went the stories, as Annie and Frank liked to tell them.

Paul Fees, Historian: They began to tell more and more tall tales about themselves. Not falsehoods necessarily, but tall tales, stories that probably had a foundation in fact, but became certainly better in the retelling, certainly better for publicity.

Narrator: In 1893, the Columbian Exposition opened in Chicago, showing off the latest technological marvels.

Buffalo Bill was not invited to join this celebration of modernity. He set up in an adjacent lot and his old time Wild West show drew larger crowds than the futuristic Exposition.

Oakley and Cody had become living symbols of the Wild West -- a place that was fast disappearing.

Paul Fees, Historian: 1893 marks the beginning of a true nostalgia for the passing of the West, and certainly focused attention on Buffalo Bill's Wild West as being somehow a preserver of the old, a showcase for those values that people were afraid were being lost.

Narrator: The Columbian Exposition glowed with a new marvel, electric light and showcased another: Thomas Edison's kinetoscope -- a primitive device for viewing movies.

In 1894, Edison invited Annie and Frank to his New Jersey studio for a test of his movie camera.

In dim, smoky images, Edison's camera managed to capture Annie's performance. But the invention also signaled the end of the Wild West Shows.

By the early 1900s, movies would become the main source of western entertainment.

But for the rest of the 1890s, Annie Oakley and Buffalo Bill were as popular as ever. All over the country, excited crowds welcomed their arrival. They played 131 cities in 1895 alone.

Then, in the fall of 1901, their train left Charlotte, NC, bound for Virginia. It never made it. A head-on collision with an onrushing freight killed much of the show's livestock. The passengers escaped with their lives, but Annie Oakley's spine was injured, requiring surgery. She decided the time had come to leave the arena, and Buffalo Bill. But it was hard to forsake the spotlight. Just a year after the accident, Annie agreed to star in a play written especially for her.

Naturally, she played a western heroine -- capturing bad guys, rescuing innocent victims, and performing her signature shooting stunts to rave reviews.

The 42-year-old Oakley seemed ready for a new career as an actress, when out of nowhere, on August 11, 1903, headlines screamed of her downfall.

William Randolph Hearst's Chicago newspapers reported that Oakley had stolen a pair of men's pants to pay for cocaine -- that she was a drug addict, now doing time in jail; that she was in a "shattered condition," "destitute" and "pitiful."

Shirl Kasper, Biographer: The Associated Press sends it across the country and all these papers pick it up, and Annie is just devastated. It's like everything she's worked for her whole life to keep this respectable reputation, is shattered.

Narrator: The Hearst story was false. The woman arrested in Chicago was a burlesque dancer posing as Annie Oakley. But the damage had been done.

Virginia Scharff, Historian: In Annie Oakley's time the threat of the taint of scandal on somebody who was an American hero and who made their fortune by being an American hero that could cost them their livelihood, it could cost them their security. And I think Annie Oakley knew at the time that this newspaper report came out just dragging her in the gutter that this was something that could absolutely ruin her, and she was personally insulted by it. But I think more that she knew as a businesswoman -- and a very savvy businesswoman -- what the cost of that kind of scandal could be, and she was willing to risk anything to make sure that that didn't happen.

Narrator: She fired off angry telegrams to the offending newspapers -- "Woman posing as Annie Oakley in Chicago is a fraud... contradict at once... someone will pay for this dreadful mistake."

Most papers quickly retracted the story. Many apologized to Oakley directly. But that was not enough.

She brought libel suits against every newspaper that had published the story.

Shirl Kasper, Biographer: She just goes after these newspapers relentlessly, suing them one after the other, you know. "I've got to clear my name. It's not about money." She -- actually, you know, Annie -- who cares so much about money, is spending money to hire fancy lawyers and to -- to prosecute this injustice that's been done to her.

Narrator: "That terrible piece ...nearly killed me," she wrote. "The only thing that kept me alive was the desire to purge my character."

Oakley became a woman obsessed. Over the course of six years, she crisscrossed the country, suing 55 newspapers. It was the largest libel action the country had ever seen.

Virginia Scharff, Historian: She had fought very hard to earn her own security, to have a good name, to be the kind of person that everybody would see as a role model and as a social icon rather than somebody who was just a dirty, poor person, and somebody who'd be a victim. She was never ever going to be a victim again.

Narrator: William Randolph Hearst fought Oakley tooth and nail. He even sent a detective to Greenville, Ohio to dig around in Oakley's past -- sure he could find something to discredit her in court.

But there was nothing to find.

Annie approached every trial with great care. The courtroom was now her arena.

Audio:

"Were you ever arrested?"

"No sir."

"Were you ever locked up an a charge of larceny in Chicago?"

"No sir."

Narrator: "The girl of the western plains" now dressed mostly in black with demure diamond earrings, her now-grey hair worn up on her head. She was reported to exude an air of "perfect refinement" and "polished courtesy."

Audio: "Did you ever say that an uncontrollable appetite for drugs has brought me here?"

"I don't know what the use of drugs (Overlapping voices) ...have upon your mental feelings? I felt as though I could never possibly face an audience until the wrong was righted... I beg your pardon, you're wrong... of dubious reputation... malicious and damaging..."

"We the jury find in favor of the plaintiff, Mrs. Annie Oakley... find in favor of Annie Oakley..."

Narrator: Oakley won 54 of the 55 cases. Hearst had to pay her $27,000. But most of the awards were much smaller.

After expenses, she actually lost money over the course of her six-year campaign.

Joy Kasson, Historian: I think her reaction to the inaccurate story in the Hearst newspapers might seem to us really excessive. She spent so many years contesting and suing one paper after another, for continuing to report an erroneous and insulting story. But I think you can understand her deep concern over that -- if you see it in the context of this need to control her self-presentation, to be the person who would define her own image. And being ladylike and being respectable was such an important part of that delicate balancing act.

Narrator: The court battles finally behind her, Annie Oakley -- now 50 -- signed for top dollar with a new Wild West show. At first she packed in the crowds, but over time the audiences dwindled.

Paul Fees, Historian: One of the things that had happened to Annie Oakley by 1910 is that she had become an artifact of the past. Her fame was founded on -- on shooting. Her fame was founded on a skill that had been necessary in the winning of the West, but was now no longer so necessary, or even so salable. The whole medium that had made her a star had lost its audience to the movies.

Narrator: Oakley retired in 1913, but was uneasy leading a life of traditional domesticity in her new home in Maryland. Annie, Frank joked, was a "rotten housekeeper."

The Butlers sold the house and went back on the road -- but now it was for pleasure, following the seasons to pursue their passions for guns and hunting.

Still, Annie Oakley never left the public eye. She used her celebrity to encourage women to be physically fit and taught thousands to shoot.

Mary Zeiss Stange, Professor of Women's Studies: She was a very early advocate of women's use of firearms for self-defense. She believed that it was thoroughly appropriate for a woman to have a gun at her bedside, and she also argued that women, especially if they had to be out and about alone, ought to think seriously about carrying firearms for self-protection.

Shirl Kasper, Biographer: This is when she starts sounding like a feminist, you know. "I think women should have the right to protect themselves and carry a gun." She even appears in the Cincinnati newspaper article, showing how to hide your gun under an umbrella so no one will know you have it. Then if someone attacks you, you can pull it out.

Narrator: Even in retirement, Oakley walked a fine line between being the powerful, self-sufficient woman, and the refined, Victorian lady.

She had once offered to lead "a company of 50 lady sharpshooters" to fight in the Spanish American war. But for the most part, she left politics to men. Annie Oakley didn't even think women should be allowed to vote.

Mary Zeiss Stange, Professor of Women's Studies: Although she did not espouse women's suffrage and she didn't talk about all of the issues that were important to the so-called "new women" of her time, arguably, Annie was living a lot of the values that her feminist sisters were arguing for. She was one of the first really hard core advocates for equal pay for equal work. She just couldn't go that extra step, to argue openly that she agreed with feminists, and perhaps she didn't. Perhaps she didn't see herself as needing feminism to achieve what she had been able to achieve.

Narrator: One afternoon in 1922, a charity event drew thousands to a Long Island race track.

The main attraction was a little woman with white hair.

She skipped into the arena, adjusted her spectacles, and signaled her husband of 46 years to begin.

"Miss Annie Oakley was the hit of the afternoon," wrote The New York Herald. "She said she felt a little out of practice, but old timers said that during the 16 years she was with Buffalo Bill she never gave a more entertaining exhibition." (The New York Herald, July 4, 1922)

It would be one of her last.

A car accident that year shattered her ankles and fractured her hip. She would never again walk without a leg brace.

It was over now. Annie had her shooting medals melted down, and donated the money to charity.

She was 66 years old, and weakening.

Some believe that lead poisoning -- brought on by years of handling lead shot -- was the cause.

On November 3rd, 1926, Annie Oakley died at home in her sleep.

It was one of the rare times that Frank could not be at her side. He himself had fallen ill while traveling in Michigan. Eighteen days later, Frank, too, was gone. They were buried beside each other in Greenville, Ohio, not far from Annie's childhood home.

R. L. Wilson, Firearms Historian: The career, the achievements, the magic of Annie Oakley is so extraordinary that you cannot imagine that anybody could have created a character like that. It had to be a real person that did what she did, and had a 66-year life of incredible experiences and achievements and adventures. That has no match in American history.

Mary Zeiss Stange, Professor of Women's Studies: If Annie Oakley were simply the cowgirl or simply the sharpshooter or simply the proper Victorian girl, she probably would have been forgotten a long time ago. But she's such a complicated package -- she's constantly challenging us to think and rethink our ideas about what it means to be female in American society.

Don B. Wilmeth, Theatre Historian: The great mythology of Annie Oakley came later when she became a subject of popular culture, probably best known in Annie Get Your Gun, which is a total disruption of what her career and life was really like. Nonetheless, the real Annie Oakley created an indelible image as the self-reliant, empowering figure at a time when women just didn't do what she did. And she managed to do it and continued to be very much the lady.

Virginia Scharff, Historian: There's never been anybody like Annie Oakley, there's never been somebody who had both the power of the gun and this power of kind of sweetness and purity that makes her safe, even though she's holding that gun in her hand.