William Bradford (Roger Rees): Now faith is the substance of things hoped for; the evidence of things not seen. By faith the elders obtained good report, and through faith we understand that the worlds were framed by the word of God.

Abel. Enoch. Noah. Abraham. Sarah. These all died in faith; not having received the promises, but having seen them afar off -- and being persuaded of them, and embracing them -- and confessing that they were but strangers and pilgrims on the Earth. For they that say such things declare plainly that they seek another country. And truly if they had been mindful of that country from whence they came out, they might have had opportunity to return. But they desired a better country -- that is, a heavenly one: wherefore God is not ashamed to be called their God: and he hath prepared for them a city.

Susan Hardman Moore, Historian: I think William Bradford knew they were on a journey in this world towards heaven. They didn't know quite how they would get there, or where they would finally meet their end. But I think that's what he meant: they were on a journey: they were transient citizens of the world, and, ultimately citizens of heaven.

And they were on a journey towards purity: that's what they sought; that's what took them out of England; that's what took them over to Holland; that's what took them from Holland over to the new world.

Narrator: Summer was fading fast, and the window for attempting the long and dangerous ocean crossing had already started to close, when on September 6th, 1620, an aging 180-ton ship called the Mayflower weighed anchor off Plymouth off the south coast of England, and set out on her own across the North Atlantic on what would prove to be one of the most historic voyages of the millennium.

Pauline Croft, Historian: It's worth reminding ourselves that at the time they were a very, very small group of very extreme people. And if we'd never heard of them ever again, nobody would be surprised. And most English people thought that they were well rid of them. The fact that they are, in the long term, extraordinarily successful -- that they found the world's greatest democracy -- throws retrospective luster. They are, one might say, if you wanted to be critical, they're religious nutters who won't settle for anything except the most literal reading of the Bible. They want to transform a nation-state into something that resembles what they take to be a Godly kingdom.

Nick Bunker, Author, Making Haste From Babylon: They weren't the people that you would expect to be founding a new colony. They weren't soldiers. They were not emissaries of a foreign government. They were not particularly well provided with supplies. And at least half of them were Separatists -- that is to say, radical Protestants who were religious exiles who had been living in Leiden in the Dutch Republic. They weren't the people you would automatically expect to be founding a new outpost of the British Empire.

Narrator: They were in many ways the least likely of task forces for establishing a permanent English presence in the New World. Fewer than 50 of the 102 passengers were adult men -- many well past their physical prime -- at least 30 were children -- and nearly 20 were women -- including three expectant mothers.

By the time they set sail, England had still not succeeded in establishing a truly viable colony on the shores of the New World -- and their chances of survival, let alone success, were all but nil.

Sue Allan, Writer: When you look at Jamestown Virginia, by 1620 they'd pumped in something like 8,000 colonists there, and, yet, they were struggling to keep their numbers above a thousand. The death rate was awful. So it was a very dangerous step to even contemplate -- especially given the number of people on the Mayflower.

Jill Lepore, Historian: They don't register at all numerically. It's a tiny handful of people -- many of whom don't survive. We're thinking about migration to the Americas, in the 17th and 18th century, we're talking about 10 million Africans, for instance -- as against this tiny handful of Englishmen and women?

The fascinating thing, then, about the Pilgrim story is how this tiny group of people managed to get by, and managed to tell the story in such a way as to erase that whole other history.

Kathleen Donegan, Literary Critic: If you ask people, "Where does America start?" -- they'll say, "It starts in Plymouth Rock." Despite the fact that Jamestown was founded in 1607 and Plymouth was founded in 1620. It became our story of national origins.

Narrator: Somehow with the passage of time, the arrival of this frail unlikely band would come to be seen as the true founding moment of America -- and the story of their coming enshrined as the quintessential myth of American origins: commemorated each year on the fourth Thursday in November at Thanksgiving -- and embodied in a handful of iconic and instantly recognizable images -- including a rock and a ship -- and a feast that almost certainly never took place as we imagine it did.

Nathaniel Philbrick, Writer: I think we feel that we're such a new country that we need to know how it all began. We need that beginning moment, and the Pilgrims serve that purpose. But what people forget is that it wasn't all fated. These were normal people, under extraordinary circumstances, and they were making it up as they went along. And it ends up being as much a story of survival as it is a story of origins.

Narrator: What no one could have imagined in the fall of 1620 -- as autumn winds blew the 102 passengers of the Mayflower, west across the Atlantic -- was how harrowing, dark and deeply unsettling their pilgrimage to the New World would be. Or how utterly their quest for a godly republic would transform the world they were sailing towards -- the searchers themselves -- and the nation that would rise up long after they were gone -- consecrated to their memory.

Kathleen Donegan, Literary Critic: Because the Pilgrims have been so enshrined in the national imagination, because they've meant so much in what we've told ourselves about who we are as Americans,. we need to go back and ask questions about why we picked that story. What it was about these people, what it was about their history that we wanted to see reflected in our own national image.

There's been a tremendous amount of memory produced around the Pilgrims. But there's also been a lot of forgetting. You know, that memory is very selective. And so to look at what's been remembered, and let that shed light on what's been forgotten is an important exercise when we're thinking about something that has been so central to our national imagination.

Bernard Bailyn, Historian: The difference is Bradford. Not simply because he was the governor for many, many years, but because of his personal qualities. He was a person of very delicate sensibilities and very keen perceptions, and he watched the flutterings of their little conventicle, and its ups and downs, with the greatest concern, and registered it in this wonderful prose.

Narrator: To a remarkable degree, we would scarcely remember the Pilgrims at all, and certainly not remember them as we do, were it not for the unusual man who came to lead them in the New World and the unusual book he left behind -- a luminous text unlike any other account of early American settlement, extraordinary both in what it says and in what it passes over in silence.

Nathaniel Philbrick, Writer: Bradford's Of Plymouth Plantation is one of the great books of American literature and history. That book, more than anything, is a kind of bible in its own way. It's steeped in the Bible, obviously, when it comes to its language. But when it comes to the history of Plymouth Colony, it is the text. And there's stuff there that is very dark and turbulent.

Narrator: He labored over the manuscript for more than 20 years -- "scribbled writings," he said, "pieced up in times of leisure," stolen from his duties as governor, and written in the third person as if to a far distant future.

He left the manuscript to his sons and heirs the day he died in 1657 along with a handful of simple poems, written in the first person. The book itself almost never came down to posterity.

Kathleen Donegan, Literary Critic: In Bradford's role as a historian, he has the possibility of success because he has the possibility to shape that history. He gets to write for posterity; he gets to shape the story. Bradford is clearly writing for a future. Plymouth, he understands, will have its future in its history, and he's the one who's creating that history.

William Bradford (Roger Rees): From my years young in days of youth,

God did make known to me his truth,

And call'd me from my native place,

For to enjoy the means of grace.

In wilderness he did me guide,

And in strange lands for me provide.

In fears and wants, through weal and woe,

A pilgrim passed I, to and fro.

Nick Bunker, Author, Making Haste From Babylon: In England, the place that is most closely associated with the origins of the Pilgrims is a village called Scrooby -- which is right at the northern corner of the county of Nottinghamshire. It's about 150 miles north of London. It was an area where religious divisions were particularly conspicuous, where there was still quite a large number of lingering Roman Catholics, an area which had recently been evangelized by radical Protestantism.

Sue Allan, Writer: You have the right people, at the right time, in the right area, with the same ideas. And I think that's what happened up here, in this part of the country. Got John Robinson at Gainsborough. You've got William Brewster there at Scrooby. You have Richard Clifton here at Babworth. You have William Bradford in Austerfield, so spiritually strong and so young. They supported each other, and I think that is why it took off here, and maybe not in other places.

Narrator: He was born in the tiny village of Austerfield, in south Yorkshire, and baptized, on March 19th, 1590 in the ancient stone church of St. Helena's -- a three-mile walk down a path called Low Common Lane -- from the village of Scrooby.

With farmland of their own and a sturdy house, his family though far from wealthy were a far from poor -- especially compared with their neighbors -- tenant farmers and landless field hands, for the most part. But his childhood would be blighted by the death of virtually everyone close to him: his father, William, when he was one. His grandfather, William, when he was six. His mother, Alice, when he was seven. His sister, Alice, and his grandfather, John Hanson, when he was 12.

He was sent to live with his uncle, Robert, who hoped he would prove useful working in the fields. By then, his family's economic security had been badly shaken by four failed harvests in a row -- the Great Death of the 1590's and by the devastating depression that followed.

Nick Bunker, Author, Making Haste From Babylon: The standard of living of the average English laborer was rapidly declining. There was something very close to famine. So it was a very uncertain world, in which even people from the yeomanry -- as the Pilgrims were -- were always worried they were about to slip back into this state of near-destitution in which many people lived.

Narrator: Lonely and intelligent, in a world that felt increasingly precarious and unmoored to him, he fell ill when he was 12, with what he called a "long sickness" -- which took him from the fields -- kept him bedridden for months -- and drove him to seek solace in the Bible.

The reading of scriptures he said, made a great impression upon him, and the more he read, the more troubled he became at the gulf between the world he saw around him, and the simplicity and purity of the gospel.

Young William Bradford (Josh Webb): Our father, who art in heaven, hallowed be thy name…

Nathaniel Philbrick, Writer: He had this profound sense as a 12-year-old that the congregation he was a part of was corrupt, that the Church was moving them in a direction that was not right, that they prayed to the depraved beliefs of mortal men that were moving them away from God. And so this was a deep conviction. And I think there you have the beginnings of a very complex, inward-looking person who was improbably preparing for the ultimate journey.

Narrator: When he was well again, he went with a friend to All Saint's Church at Babworth, 10 miles away, to hear the "illuminating ministry" of a forward-thinking Puritan preacher, named Richard Clyfton.

Not long after, he found his way down Low Common Lane, to the home of William Brewster -- the warm-hearted Cambridge-educated postmaster and bailiff of Scrooby Manor -- where he came to feel he had found a spiritual home -- and where each week, a private congregation gathered to hear Richard Clyfton -- and another charismatic minister, named John Robinson -- preach on the need to purify worship of everything worldly -- of anything not contained in scripture.

Susan Hardman Moore, Historian: I think the sense of faithfulness to Scripture is at the heart of it. They want to go right back to the roots and strip away all the human accretions that have come into the worship and the life of the Church, and get back to a primitive purity. And it's no accident that the larger movement from which the Separatists came were called Puritans by their opponents because that's what they were campaigning for -- greater purity, greater faithfulness to what they believed they read in Scripture.

Narrator: Nothing he read made a deeper impression on him than a passage from the book of St. Matthew, in which Christ explains to his disciples where the true church lies.

Young William Bradford (Josh Webb): For where two or three are gathered together in my name, there am I in the midst of them.

Pauline Croft, Historian: That's obviously the key Separatist text -- that Christ will be with you without a bishop; without a church; without any clear ecclesiastical organization. And that prayer, conversion, commitment is enough for the presence of Christ. That's an extraordinarily radical text when you think about it.

Nathaniel Philbrick, Writer: It's a powerful idea to think that you can, in an unmediated way, see God. The Bible is your window in. And to have a bishop or a pope telling you what to do is just getting in the way, is so much fallen static. And it's a powerful idea, and I think it's particularly powerful for someone like Bradford, who finds himself alone at 12. And to think that God is that accessible -- that if he can find just a few others, and have a congregation of people on the same wavelength, that they can find their way to God, that's what you need. That's all you need. And you're willing to go to the ends of the Earth literally, if you know that you will be following that path.

Narrator: By 1603, he was fully committed to the radical idea that the true love of God might mean separating from the Church of England altogether.

Sue Allan, Writer: And that's when the real trouble begins. Because you look at who's the head of the only Church in England, the head of the Church from Henry's time is the monarch. It's not just the Church -- it's the monarch that you're flying in the face of. That's what makes this so dangerous, and so worrying for the authorities. Because if you're going to make a stand on religion and get away with it, then what else are you going to make a stand on?

Michael Braddick, Historian: The issues at stake are literally more important than life and death -- it's your eternal life or your eternal death. And if your monarch is jeopardizing your eternal life, you're a very unreliable subject. Because anyone who separates from the Church, is not just separating from the Church, but they're separating from royal authority. And that's potentially very dangerous.

Sue Allan, Writer: Bottom line, what was at stake? Well, their lives. You can punish somebody. For not attending a church, you can be fined. And it was 20 pounds in those days -- about 9,000 pounds in today's money. That's a lot of money -- just for not going to church. If you persisted, then you could be imprisoned, so you could think about it. And Elizabeth, after the Act Against Puritans in 1593, had made the next step banishment. But I think, with James, the next step could have been death for these people. He was newly to the throne -- not popular. He wasn't going to have any dissenters. So I really think that these folk were risking everything.

Susan Hardman Moore, Historian: And in areas like this, where people had been, perhaps, able to get away with things, there was a new drive to make sure that everyone conformed to the Church of England. And there were explicit rules that said you couldn't have private religious meetings in houses. Ministers should not convene private groups of people. These conventicles were judged illegal and subversive to order in the realm. And for that reason, a network of people here came to feel that they were under pressure.

Narrator: In the fall of 1607, when William Brewster himself was fined, and threatened with imprisonment -- it was clear that only one option remained. To worship God as they saw fit, they must separate not only from the English church, but from England altogether.

Michael Braddick, Historian: Holland had emerged as the Protestant part of the Netherlands opposed to Catholic rule in the South. It was a place of refuge for evangelicals in a time of threat and challenge. So you can see the attraction. From here to the Humber Estuary and to Amsterdam is not very far.

Sue Allan, Writer: But, they couldn't just leave the country. Because you needed permission to pass port. And dissenters weren't going to get permission to leave the country. They'd have to escape from their own country.

Narrator: A first desperate attempt to flee ended in disaster when the English sea captain they had hired betrayed them to the authorities.

Eight months later, on a cloud-darkened evening in the spring of 1608, they tried again -- some fleeing by barge down the Trent and the Humber towards Hull -- where this time 16 of the men -- including 18-year-old William Bradford -- managed to board a Dutch ship and get away to sea -- one step ahead of the searchers in pursuit -- who arrested the terrified women and children, and carted them off to jail.

They were soon released; and over the next year, in groups of two and three, quietly made their way across the North Sea to Amsterdam, and joined their friends and family members in exile.

Pauline Croft, Historian: And so they join the radical Protestants of their time, the Dutch. For James, for the monarchy, it was "Let them go there, if that's where they're happy, no reason why they shouldn't go there. The Dutch are our allies, we've been fighting on the side of the Dutch. If you want to live there, fair enough. Good riddance." And, no doubt, many of them would have thought that they would settle there quite happily, and that would be it.

Sue Allan, Writer: These folk mainly were tied to the land. They were used to England. As far as we know, only William Brewster spoke the language, and you're going to a country where you don't speak the language, you don't know the customs. How are you going to survive? And there was no coming back.

Narrator: In 1609 -- fearing the congregation would come apart in the sprawling Dutch metropolis -- William Brewster and John Robinson led their people 22 miles south to the city of Leiden -- a university town, and the bustling heart of the Dutch textile industry.

Nathaniel Philbrick, Writer: Holland was a completely different environment from what they were used to, and because they were foreigners, they ended up getting really lousy jobs. Instead of farms they ended up basically in little factories, creating clothing, and they would work, literally, from dawn till dusk. A bell would go off in the morning, and they'd work to the very end of the day -- often with their children.

Narrator: With no family of his own, William Bradford found lodgings in a poor neighborhood called Stink Alley until, at 21, he was able to set up shop in a small house of his own, toiling six and sometimes seven days a week as weaver.

Pauline Croft, Historian: It's clear that many of them found it very harsh: the climate was far harsher than they'd expected; the difficulties that they encountered were much greater.

Narrator: But for all the trials and hardship, they would look back these on years with an almost rapturous longing and nostalgia -- for the world they created around them there, free for the first time to worship as they wished, in accordance with God's will, unmolested.

William Bradford (Roger Rees): Such was the true piety, the humble zeal, and fervent love, of this people (whilst they thus lived together) towards God and his ways, and the single heartedness and sincere affection one towards another, that they came as near the primitive pattern of the first churches, as any other church of these latter times have done.

Susan Hardman Moore, Historian: I think there's something about what you might call the "glory days" in Leiden. The community that John Robinson builds around himself -- his house, the sort of cottages surrounding it, the meeting hall -- it's very much based on what they read in the letters of the early Churches -- Paul's letters in the New Testament -- about what it means to be a community in the body of Christ. They would take a vision of what that had been for them in Leiden across the Atlantic to the New World.

Narrator: In 1613, William Bradford married a young English woman named Dorothy May -- not in a religious service performed in a church, but in a civil ceremony at Leiden's grand city hall -- in accordance with Dutch custom, and because the Separatists found no precedent in the Bible for church ordained weddings.

It was the beginning of the separation of church and state -- another custom they would take with them across the Atlantic -- sooner than anyone could have imagined, as by 1617 it had begun to be clear that Leiden was not the promised land after all.

Nathaniel Philbrick, Writer: Their biggest concern after a decade in this foreign land was that their children were becoming Dutch, and these people had decided to leave England for their religious beliefs, but they were still very proud of their English heritage. And so if we stay in Holland, we will lose the identity that is so essential to who we are. They were also fearful that the Spanish were about to attack again.

Narrator: In late November 1618, a brilliant blue-green comet appeared in the night skies. "We shall have warres," the English ambassador to the Netherlands wrote, and he was right.

Nick Bunker, Author, Making Haste From Babylon: Europe was on the verge of an enormous conflict, the beginning of what we now refer to as the Thirty Years' War. A great religious conflict, involving all the great powers of Europe -- which Protestants such as the Pilgrims saw as a great confrontation between good, in the shape of Protestant Christianity, and evil, in the shape of Roman Catholicism. And this, in the eyes of many, was a cataclysmic global confrontation, which might very well lead to the end of the world. It might herald, if you like, the Second Coming of Christ and the Day of Judgment. Things were that urgent. The stakes were that high.

Nathaniel Philbrick, Writer: Everything seemed to be on the edge of complete meltdown. And so they decided it's time to pull the ripcord once again, even if it meant leaving everything they had known all their lives.

Sue Allan, Writer: But where do you go? You're Englishmen, after all, but you can't go back to England. And I think that's why they plumped for the New World. If you can't go back to England, at least maybe they could the find the freedom they're looking for there.

Narrator: After weighing and rejecting numerous options, they settled in the end on an area at the mouth of the Hudson River -- near present day New York -- in the northern most part of the English colony founded by the Virginia Company, then set out to try and get a legal charter, and permission to emigrate.

Nathaniel Philbrick, Writer: What they had to do to get there required an awful lot of them. They really had to figure out how they were going to do this. And like many people from cults, they were really naive when it came to the rest of the world. And so it meant that they were very prone to being duped when it came to trying to figure out, "How are we going to do this? Who are we going to hire? Who's going to be our military officer? Where are we going to find a ship? Who's going to finance this endeavor?" And these were not wealthy people. And so they had this huge list of problems.

Narrator: They had all but despaired of finding anyone willing to finance the hugely costly, high risk undertaking, when in early 1620, they were approached in Leiden by a 35-year-old broker from London named Thomas Weston -- who offered to organize financing for the expedition through a group called the Fellowship of the Merchant Adventurers.

Susan Hardman Moore, Historian: And that is the beginning of all sorts of trouble for them! The right time to make that westward crossing of the Atlantic is to set out in the spring. So the Pilgrims get themselves ready in Leiden, and it's June when they discover that Weston hasn't organized any transport.

Narrator: To their deep dismay, Weston also now informed them that the investors were getting cold feet and insisting that non-Separatist outsiders go along with them. The prospect was appalling -- but there was nothing they could do.

In June -- with no word about financing or the ship Weston swore would be waiting for them in Southampton -- they arranged their own passage across the channel on an aging vessel called the Speedwell.

On July 22nd, they bid a heart-wrenching farewell to those staying behind, including Pastor Robinson, who, it was decided, would remain in Leiden with the main congregation until a secure beachhead had been established. In anguish, William and Dorothy Bradford left their three-year-old son, John, in the care of relatives.

John Demos, Historian: There was deep sorrow at the bottom of this decision for many of them. As they got on the boat, they knew, at least most of them, had no chance to come back. They were never going to see the people who had meant most to them up to that point. They were going to something they could barely imagine.

William Bradford (Roger Rees): And so they left that goodly and pleasant city which had been their resting place for near twelve years; but they knew they were pilgrims, and looked not much on those things, but lift up their eyes to the heavens, their dearest country, and quieted their spirits.

Narrator: The journey across the channel to Southhampton was swift and uneventful; and when they arrived, to their enormous relief they found waiting for them at the dock a second ship, which Thomas Weston had secured for them at the last possible moment: a medium-sized 180-ton square-rigged merchant vessel, battered from use, but at a hundred feet, three times longer than the Speedwell -- seasoned and sweetened from years of shuttling across the channel, taking bales of wool to France, and barrels of wine back to England. It was called the Mayflower.

Here, too, they had their first encounter with the Mayflower's captain, Christopher Jones, and with its hardbitten, rough-and tumble crew. And with the "Strangers" -- the motley assortment of non-Separatist recruits the investors had insisted go with them.

Nathaniel Philbrick, Writer: Suddenly these Leideners, who had spent 10 years cultivating their own spiritual and very inward bond, found themselves on a ship -- sharing their space with the "Strangers," who came from a completely different place with the understanding that: "We're not just sharing the ship with them, we're gonna be living with these people for the foreseeable future."

Narrator: The Mayflower and the Speedwell had finally weighed anchor -- and were just beginning to make headway when to their shock and dismay the Speedwell began to wallow and take on water.

Susan Hardman Moore, Historian: It sprang leaks like a sieve. They kept on having to put back into port, because the Speedwell was leaking. And, finally, in Plymouth, they had to abandon the Speedwell altogether. And everyone went aboard the Mayflower and set off.

Narrator: It was up to the Mayflower now to sail on on her own -- crowded with as many passengers from both ships as she could hold. Many had to be left behind.

When all was said and done, there were only 102 passengers on board -- only half of whom were members of the original Leiden congregation.

Nick Bunker, Author, Making Haste From Babylon: It was a long process before they could finally get away to sea, out onto the open Atlantic. And, it was far too late in the year. If you wanted to go to America, to Virginia or New England, you should try to leave in February or March, at the latest, so you could get there in the spring, and give yourself a full spring and summer to become accustomed to the new world and to do all the things you had to do before the winter set in. In fact, of course, they ended up leaving in September, which was about as bad as it could be.

Narrator: On September 6th, 1620, fearfully late in the season, under-supplied and overcrowded, with autumn storms already whipping the north Atlantic into menacing furrows of white capped waves, the Mayflower left Plymouth harbor and set out on her own across the Atlantic.

Edward Winslow, a 24-year-old printer traveling with his wife, Elizabeth, never forgot the moment they set sail.

Edward Winslow (actor, audio): Wednesday, the sixth of September, the winds coming east north east, a fine small gale, we loosed from Plymouth, having been kindly entertained and courteously used by divers friends there dwelling.

Narrator: The Mayflower lost sight of Land's End sometime towards the end of the first week of September. It was starting to gale. William Bradford remembered her finally setting forth under a "prosperous wind."

Susan Hardman Moore, Historian: When they finally set sail, they're going against the prevailing westerly winds, they're struggling against the Gulf Stream, and they made incredibly slow progress -- two miles an hour across the Atlantic.

Nathaniel Philbrick, Writer: Some of them had tried to create little cabins within this, which just made these little suffocating cells. And chamber pots everywhere. There was a boat that had been cut up into pieces that some people were trying to use for a bed. There were two dogs -- a spaniel and a giant slobbery mastiff. And it is a voyage from hell.

Bernard Bailyn, Historian: They almost turned back. The sailors, at one point, said they'd be happy to earn their wages, but they were not going to risk their lives. Bradford spells it out -- he describes it as awful. And these terrible sailors, who were a blight on humanity, and the Strangers, some of whom were worse, loaded up with all this gear -- animals, people. It's amazing that they came out alive.

Nathaniel Philbrick, Writer: And, by the end of it, people are getting sick. And so there was a real sense of urgency aboard, particularly for Master Jones, who knew at some point he had to get these people off his ship.

Narrator: Two people had died, and more were failing fast when early on the morning of Thursday, November 9th, 1620 -- after more than two months at sea -- a crew member spied a line of high bluffs gleaming far off in the early dawn light, and shouted out excitedly to Captain Jones.

It was the first land they had seen in 65 days. But their jubilation quickly dimmed as word raced through the ship that they had made landfall far north of their intended destination.

Nathaniel Philbrick, Writer: They've arrived off the coast of Cape Cod, but they're 200 miles off-course. And so Master Jones heads them south, towards the Hudson River. And unfortunately, there are no reliable charts. And they unsuspectingly find themselves in one of the most dangerous pieces of shoal water on the Atlantic coast. They're in the midst of what Bradford would call "roaring breakers," and it looks like this is going to be the end of them. And Jones makes a very historic decision. He says, "We're not going south -- we're gonna take this breeze to the north" around the wrist of what they called Cape Cod, to whatever harbor is there, "and I'm getting these people off my ship."

Narrator: On November 11th, 1620, they rounded the tip of Cape Cod and sailed into the relative calm and safety of the great bay where, even before they dropped anchor, long festering tensions between the Strangers and the Pilgrims broke out into the open.

Having landed so far north of the boundary of their legal patent, many of the Strangers insisted they were now bound by nothing at all -- and began to speak openly of splintering off and going their own way, once they came ashore.

William Bradford (Roger Rees): This day -- before we came to harbor -- observing some not well affected to unity and concord, but gave some appearance of faction -- it was thought good there should be an association and agreement that we should combine together in one body, and submit to such government and governors -- as we should by common consent agree to make and choose -- and set our hands to this that follows word for word.

Narrator: William Brewster, in all likelihood, drafted the short agreement -- little more than a single sentence long -- stating that they agreed to combine themselves "together -- into a civil body politic" with the power to enact whatever laws proved necessary to preserve the group.

John Demos, Historian: The point of the Compact was to ward off the danger of division and dissolution after they got to the other side. The thing that's key about it is it's a contract. It's not exactly an elaborate plan for democracy. It's a contract: "We're going to agree on this particular goal, and get everybody's name on this document, and make a commitment to this."

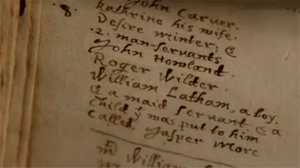

Narrator: On the morning of November 11th, 1620, the Mayflower compact was offered up for signature. The first to sign was John Carver, one of the wealthiest men on board; the last, a servant named Edward Leister. In the end, the vast majority of the men on aboard put their names to the paper -- 41 adult men in all -- 90 percent of the adult male population of the Mayflower.

Years later -- when William Bradford and others codified the rules of Plymouth Colony in a new Book of Laws, on the very first page they described the Compact as "a solemne & binding combination" whose authority came from the fact that it was based upon the vote of the governed.

Although the Compact began with an affirmation of loyalty to King James, the Book of Laws made clear that at times of political crisis, the authority of the monarch could sometimes be suspended, while the consent of the governed could never be. Once the signing was complete, the colonists acted collectively for the first time and elected John Carver to be their governor.

At least for the moment -- from the relative safety of the ship at anchor in Cape Cod Bay -- the threat to the corporate integrity of the colony had been averted.

William Bradford (Roger Rees): Being thus passed the vast ocean, and a sea of troubles, they now had no friends to welcome, or inns to repair to, for to refresh their weatherbeaten bodies, no houses much less towns to repair to, to seek for succor. And for the season it was winter, and they that know the winters of that country know them to be sharp and harsh -- subject to cruel and fierce storms. Besides what could they see but a hideous and desolate wilderness, full of wild beasts and wild men?

Narrator: On November 11th, with their ship safely anchored off the tip of Cape Cod -- a landing party of 16 armed men -- including William Bradford, Edward Winslow and the veteran English soldier they had hired, Miles Standish -- ventured ashore in a small boat and stepped on dry land for the first time in two months.

Though they walked for hours amongst the windswept dunes, before returning to the Mayflower with a boatload of freshly cut fire wood -- on their first excursion ashore they found no wild beasts -- and stranger still, no sign of any human presence at all, wild or otherwise.

Back on the ship, as the sun went down, the enormity of their situation began to sink in upon them. There on the edge of the dark whispering continent -- time seemed to stand still for the immigrants -- then widen into an ominous void.

William Bradford (Roger Rees): For summer being done, all things stand on them with a weather beaten face; the whole country, full of woods and thickets, represented a wild and savage view. If they looked behind them, there was the mighty ocean which they had passed, and was now as a main bar and gulf to separate them from all the civil parts of the world.... Let it also be considered what weak hopes of supply and succour they left behind them.... What could now sustain them but the spirit of God and his grace? May not and ought not the children of these fathers rightly say: "Our fathers were Englishmen which come over this great ocean, and were ready to perish in this wilderness; but they cried unto the Lord, and he heard their voice, and looked on their adversity, etcetera." Let them therefore praise the Lord, because he is good, and his mercies endure for ever.

Linda Coombs, Wampanoag Historian: In southeastern Massachusetts, east of Narragansett Bay: that's Wampanoag territory. To the north of us was the Massachussett; to the west the Nipmuc; to the south were the Narragansett - the Pequot - Mohegan - Niantic. We estimate that within that area we had about sixty-nine villages. A village could be anywhere from 100 people to 2,000. So, rounded off at 1,000 average and you've got close to 70,000 people.

In 1616, before the coming of the Pilgrims, there was a huge plague. It started in Maine, brought over by European fishermen. It swept a 15-mile-wide path right down the coast, sort of took a left through the middle of Wampanoag country and stopped at Narragansett Bay. The Wampanoags, and I think any other group that it hit, suffered anywhere from a 50 to a 90% loss in population.

Kathleen Donegan, Literary Critic: It happened so quickly. The means of death were so sudden, and, yet, relentless. And English fishermen, explorers, come to the coast and say it's absolutely abandoned. It's devastated. Where did the people go? And from that time to 1619, that's what they found -- emptiness, abandoned villages, bones scattered around the ground.

Tobias Vanderhoop, Chairman, Wampanoag Tribe of Aquinnah: In some of the accounts they found just bones bleached, not because we didn't have rituals and observances, but because there wasn't anybody left to take care of the ones who had passed away.

Narrator: Nowhere was the devastation more complete than in a village the Wampanoags called Patuxet. One villager named Tisquantum -- kidnaped two years before the plague began and carried off in chains to Europe -- returned in 1619 to find his village completely abandoned.

Tobias Vanderhoop, Chairman, Wampanoag Tribe of Aquinnah: Tisquantum was fortunate -- along with others who had been kidnapped from Wampanoag territory -- to make their way back home, only to find the devastation that has occurred. Patuxet is gone.

Kathleen Donegan, Literary Critic: It was a village of about 2,000 people. And when Tisquantum came back, not one had survived. No one. He was the only survivor of his entire village. It's unimaginable -- the grief, the loss of that. And this is the world into which the Pilgrims enter.

Margaret Bruchac, Anthropologist: It's very convenient for the telling of American history to start with the plague to start with this massive death. But when those plagues happen, they are not as total as they appear. There are some areas that were virtually untouched by the plague. It was not so empty that it was ready to be reoccupied by someone from across the ocean.

Tobias Vanderhoop, Chairman, Wampanoag Tribe of Aquinnah: But, when they arrived in this territory, they believed that their journey was ordained by God -- that they had a mission that they were to fulfill. And the desolation that they found was God's providence. It was meant to be that way for them.

Margaret Bruchac, Anthropologist : They did not view native people as humans. They saw them almost as beasts and vermin - who were cleared away by God's pestilence to make room for God's chosen people. And so I think it's necessary to ask who the savages were? Were they the people who had lived in this territory for millennia? Or were they these people who forced themselves in to someone else's home?

Narrator: They spent their first month tethered to the ship -- while three successive scouting parties probed their way down the long arm of the cape towards the mainland -- looking for fresh water, and a suitable place to settle for the winter.

On their first day out, they caught sight of six men and a dog walking far down the beach -- the first native inhabitants they had seen. The men stared back at them for a moment -- then whistled for the dog and disappeared into the line of trees. As they moved through the strange and inscrutable landscape -- filled with signs of human presence they could see but not understand -- their first halting forays had a primal, transgressive, unsettling character to them.

Kathleen Donegan, Literary Critic: In the first scouting mission, they found a sand mound and started to dig it up. And they realized this might be a grave, so they stopped digging. Bradford doesn't report that in his history. Edward Winslow does. What Bradford reports is coming on another place. Finding the same kind of mounds, digging it up, and finding baskets of corn. They take away half the corn.

Then what happens on the second scouting trip Bradford doesn't report at all, but Winslow gives us a long account of a smaller group going in through the woods, to an Indian village, and finding something that looks like a grave. So they begin to dig and this time they continue -- they start taking out the goods, they start taking out the planks, they start taking out the mats until they find two bundles -- one larger and one smaller. They open up the first bundle, and the first thing they notice is that it's full of this fine red powder -- that has a kind of smell -- they say it's not a bad smell, but the smell comes up to them. They look further in and they see the bones and skull of a man. The face still has skin clinging to it. But what's most startling is that the skull is covered with blond hair. So they know that this is not an Indian, but the body of a European.

They open up the second mat, and find the bones and the skull of a child. And the child's body is decorated with white Indian beads and bracelets, and there are little childish things around. So there's this mystery: "What has happened here? Who are these bodies? What are they doing in the same grave? What was the relationship between these dead bodies and the living hands that put them there?" And they cannot construct a narrative about that.

And this makes them think of their own situation: "How will we die here? Whose hands will attend to us? What will happen to us here?"

Narrator: They moved on. A few nights later, at a place called First Encounter Beach, they were attacked in the dark by a party of warriors. For hours the air was filled with war cries and whistling arrows, which they answered with deafening blasts of musket fire, until the attackers withdrew.

"Thus it pleased God," William Bradford wrote, "to vanquish our enemies and give us deliverance."

Finally, on December 8th, on the far western shore of the bay, they came upon a site they determined might suit them for a settlement.

Bernard Bailyn, Historian: It was an Indian settlement that had been abandoned. It seemed, physically speaking, a proper place. And it had a nice slope down to the harbor and fields beyond, and that seemed to be a convenient place.

Margaret Bruchac, Anthropologist: And one of the sad tragic ironies is that the place that the Plymouth colonists settle on for their location is the village that was perhaps the hardest hit of all the Wampanoag villages -- Patuxet -- to the point where there are bodies lying on the ground that can not be buried, because there are no relatives. And from a Native perspective, you would not reoccupy those places. So people must have thought the Pilgrims were insane to come and settle in a place where there's been so much death and loss.

Narrator: On December 12th, the third and final scouting party sailed back across the bay to the waiting Mayflower -- where William Bradford was greeted with staggering news. Five days earlier, his 23-year-old wife, Dorothy, had somehow fallen overboard while the ship lay at anchor, and drowned in the icy waters of the bay.

Sue Allan, Writer: The decks were icy. She could have slipped overboard. She could equally have been suffering from depression. Maybe it was too much leaving her child behind. Maybe with the advanced scurvy, which can give you the feeling of not just depression but of being doomed, did she slip herself into the water?

Nathaniel Philbrick, Writer: And to this day, people are wondering: "Well, was it just an accident?" And we have a tendency, I think, to think that people of this enormous religious belief would never take their life. And that's not the case at all. And the fact of the matter is, despair was a huge part of what all of them were feeling. A child had just died, the day before her death.

Narrator: William Bradford never spoke of Dorothy's death in his history; and the circumstances were never explained. Late in life he penned the lines of a simple poem.

William Bradford (Roger Rees): Faint not, poor soul, in God still trust,

Fear not the things thou suffer must;

For, whom he loves, he doth chastise,

And then all tears wipes from their eyes.

Narrator: On Friday, December 15th, 1620, with its cargo of sickened, and sea-weary passengers and crew, the Mayflower sailed west across the vast windswept bay -- towards the dark wintry shore that awaited them.

Nathaniel Philbrick, Writer: They arrive just at the worst possible time. Winter is just coming in. And it's the end of December by the time they begin to start building houses.

Susan Hardman Moore, Historian: The Mayflower had to anchor a mile offshore, because the harbor at Plymouth wasn't deep enough to let the ship right up. So that they had to ferry the supplies, the goods, so slowly in from the Mayflower. And they managed to build only very few houses -- far fewer than they had anticipated.

Bernard Bailyn, Historian: Everything was wrong. I mean they had to reach the shore by wading through ice-cold water to the shoreline. And, Bradford says, at one point with sleet beating at them, they were covered with this ice glaze. And they caught cold and they died.

Edward Winslow (actor, audio): Friday, 22nd. The storm still continued, that we could not get a-land nor they come to us aboard. This morning good-wife Allerton was delivered of a son, but dead born. Sunday, the 24th, our people on shore heard a cry of some savages -- which caused an alarm, and to stand on their guard, expecting an assault. But all was quiet.

Narrator: They had just set to work building a 21-square foot common house for protection against Indian attack when the temperature dropped, and the weather closed in mercilessly. One by one, the weakened immigrants began to succumb to dysentery, pneumonia, tuberculosis, exposure.

Susan Hardman Moore, Historian: That first sickness, that general mortality, must have been so pervasive. At one time in that first winter, two or three people were dying every day. The number of people who were sick and needed caring for -- it must have been overwhelming. I think there is something particularly devastating about what happens to them that first winter.

Narrator: By February, people were dying in droves -- some huddled in the makeshift settlement -- many more back on the Mayflower, which had been converted to a hospital for the sick, and a hospice for the dying.

Sue Allan, Writer: The conditions onboard that ship must have been absolutely awful. They can't go ashore. They're all suffering from scurvy. That sweet ship, the Mayflower -- by the end it was like a death house on the water.

William Bradford (Roger Rees): It pleased God to visit us then with death daily, and with so general a disease that the living were scarce able to bury the dead, and the well in no measure sufficient to tend the sick.

Nathaniel Philbrick, Writer: By the spring, half of them are dead. Fifty-some people die that first year. And, by all rights, they all should have died given how ill-prepared they were.

Narrator: What happened that first winter was more than most of the grieving survivors could bear. The full horror of what they went through was fated to live on only in the margins of history.

Kathleen Donegan, Literary Critic: In Bradford's history, he really turns away from the corpses. There's no record of burials, which, with mass mortality -- with the dead outnumbering the living -- would account for a major activity of the group. So the question becomes, "What happened to the dead?"

And what we do know is hidden in a piece of court testimony, by a man named Phineas Pratt. He came in 1623, to find the Plymouth Colony completely devastated. And he asks, "Where are the rest of our friends?" And the answer, he reports, is, "God took them away by death. And we were so dejected, and so frightened that first winter, that those who could carried our sick men into the woods, and propped them up against trees with their muskets by their side, so that the Indians, looking in through the forest, would think that we had a guard -- a forest sentinel." So, the well, Bradford tells us, are nursing the sick, but what Phineas Pratt tells us is those who have strength are carrying the sick and dying bodies into the woods and propping them up against trees.

Later, when Increase Mather is writing a history of Plymouth, he quotes Phineas Pratt, but right at that terribly transgressive moment, Mather changes the story and inserts, instead, that they buried their dead at night, so as to keep their losses from the Indians. And then, as the story of the Pilgrim dead gets told and retold, the story of night burials starts to get remembered and cherished and elaborated. It comes to be not only that they do night burials, but that they plant corn over the graves so that the Indians don't notice how many losses that they have. But what really happened gets completely dropped out of the history. It is too transgressive and very dangerous, as the story about the corpses falling in the wilderness comes to pass.

And this place becomes this place of death -- both Native and English, and so they had to make some kind of meaning out of that. It couldn't just be a wasteyard of bones for everyone. They have to mean differently. So they started to assign different meanings to Indian death and English death. Indian death were just bones scattered on the ground -- were forgotten people, were just material. Indian death was about becoming carrion, waste, dispossession. Whereas English death was about becoming the seed, buried, possession. English death was going to be remembered, was going to be honored.

And Bradford makes very much of this, because in his history, what he has to do is plant those people in Plymouth to make a kind of permanence there -- to claim that ground as a ground of history. So putting bodies into the ground, even though they're "scarce buried," is a way of making that ground sacred. It could be that the most important thing that the people of Plymouth planted was their dead.

Narrator: The days were growing longer and the death rate had finally begun to subside when on Friday March 16th, cries of panic and alarm rang out as a lone warrior -- naked except for a loin cloth, and carrying a bow -- broke cover from the line of trees near their huts and walked boldly into the camp.

Edward Winslow (actor, audio): He saluted us in English, and bade us welcome, He was the first savage we had met withal. He said his name was Samoset. He told us the place we now live is called Patuxet, and that about four years ago all the inhabitants died of an extraordinary plague, so as there is none to hinder our possession, or to lay claim unto it.

Kathleen Donegan, Literary Critic: The Wampanoags are looking for an ally. They're suspicious of the Pilgrims when they first come. They stay away from them at first. They watch them. But, eventually, they realize that an alliance is going to be best for them as well.

Tobias Vanderhoop, Chairmain, Wampanoag Tribe of Aquinnah: It was not just political convenience - it was survival. If you do not have power backing you, and you are a weakened people then the enemies that naturally exist around you will take advantage. And our leadership knew very well the tough decisions that needed to be made at the time in order to ensure that Wampanoag people continue to exist in Wampanoag territory.

Narrator: Six days later, the emissary returned, bringing the principle leader of the Wampanoags, their Massasoit, and 60 of his men, including Tisquantum, the sole survivor of Patuxet who served as interpreter as the two sides concluded a remarkable treaty, agreeing, among other things, not to harm each other's people, and to come to each the other's aid in the event of attack. It was also agreed that Tisquantum would remain with the struggling group on the site of his former home to help with the spring planting.

Nathaniel Philbrick, Writer: Both peoples were in a survival situation. The Wampanoag had been devastated by disease in the three years before, and the neighboring Narragansetts were threatening to really take them over. The Pilgrims were obviously very close to losing everything after that first winter. And so they began to form an alliance with Massasoit and the Wampanoags, and I think that defined so much of what happened in that first and second year.

Narrator: Two weeks after concluding the treaty, the immigrants gathered at the harbor to bid a somber farewell to the Mayflower, which on April 5th, 1621 set sail for England, with Captain Jones, an empty hold, and a drastically diminished crew. It was one of the last voyages she would ever take. In less than a year, Captain Jones himself would be dead, and two years after that, the Mayflower, rotting at anchor on the Thames, would be sold for scrap, and disappear to history.

The Pilgrims' only anchor and lifeline was gone. They were on their own. With the return of warm weather, they put in their first crops under Tisquantum's careful supervision, planting herring in yard-wide mounds of earth sewn with corn seed, and adding once the corn came up seeds of squash and beans. The coming of spring did not entirely halt the sad toll of death.

William Bradford (Roger Rees, audio): In this month of April, whilst they were busy about their seed, their Governor (Mr. John Carver), came out of the field very sick, it being a hot day; he complained greatly of his head, and lay downe, and within a few hours his senses failed -- so as he never spake more till he died. Shortly after William Bradford was chosen Governor in his stead. And by renewed election every year, continued sundry years together -- which I here note once for all.

Narrator: All through the warm summer months, the grieving immigrants labored to make a world for themselves -- building houses, tilling soil, fishing for cod and bass in the bay. In June, they made their first tentative efforts to trade with the native groups around them. In July, William Bradford sent Edward Winslow and Stephen Hopkins to visit the Wampanoags in their village, 40 miles to the west, to build on their alliance and to find out whom they had stolen corn seed from the previous December, and to make reparations.

Autumn came, and the days dipped down into darkness. By October, they had finished erecting 11 crude structures in all -- seven dwelling-houses -- and four common buildings. They had also managed to bring in a successful harvest of corn, thanks to Tisquantum, and as the leaves began to turn, they prepared, Edward Winslow reported, to in a "special manner rejoice together after we had gathered the fruit of our labors." No one at the time called it Thanksgiving. William Bradford made no mention of it in his history.

Linda Coombs, Wampanoag Historian: There isn't much of a record. There's a paragraph, I think, in Winslow, that describes what's come to be known as the first Thanksgiving. It says nothing about an invitation. It was just that the English were doing this thing, and Massasoit showed up with these 90 men. They stayed for three days -- they went out and got five deer to add to what the English were cooking. They played games together. There's like four little facts of what happened, and then the rest of it is fluff that's been added over the centuries.

Narrator: Two and a half centuries later, at another American moment of great trial and suffering, the humble event, all but disregarded by the Pilgrims themselves, would be recast as one of the most important and defining moments in American history.

Kathleen Donegan, Literary Critic: We love the story of Thanksgiving because it's about alliance and abundance and envisioning a future where Native Americans and colonial Americans can come together and celebrate the providences of a single God. But part of the reason that they were grateful was that they had been in such misery; that they had lost so many people on both sides. So, in some way, that day of thanksgiving is also coming out of mourning; it's also coming out of grief. And this abundance, that is a relief from that loss. But we don't think about the loss, we think about the abundance.

Narrator: On November 9th, 1621, a shout went up from a lookout on Burial Hill, followed by the loud booming of a cannon -- as far out in the bay the first sails they seen since the departure of the Mayflower loomed on the eastern horizon. They had had no contact with the outside world for more than a year. Though they feared at first it might be French pirates, it turned out to be an English relief ship, called the Fortune -- sent by their mercurial broker -- Thomas Weston.

A third the size of the Mayflower, the tiny vessel carried 35 new recruits, to Bradford's dismay, only a handful of them Separatists, no supplies to speak of -- more mouths to feed just as winter came on again -- and a stinging letter from Thomas Weston himself rebuking the colonists for having failed to send back any cargo with the Mayflower.

When the Fortune weighed anchor four weeks later, they freighted it with as much beaver fur and timber as they could muster, but it was nowhere near enough to make a difference.

Nick Bunker, Author, Making Haste From Babylon: They desperately needed to find something they could ship back to England to pay their debts. And that just wasn't available in those early years in New England. So there were all kinds of challenges, which they were not well-prepared for.

Narrator: Over the next 18 months, as the pilgrims struggled to stay alive and keep their group together, they would face staggering new challenges, on not one but three fronts simultaneously: economic and demographic, as they struggled desperately to make ends meet, and to contend with the influx of what William Bradford called profane and disorderly outsiders; but also military, as it soon became terrifying clear that their alliance with the Wampanoags would not be easily replicated with other groups in the region. The struggle with those challenges would change them forever.

Kathleen Donegan, Literary Critic: Part of that has to do with living in a world where it suddenly seems that no holds are barred, where you're being forced to do things that you never thought that you would be forced to do, and you're willing to do things that you never thought that you would be willing to do.

Narrator: Ominous rumors had been swirling around the settlement for months -- first that the Narragansetts, then that the Massachusetts -- were planning to attack, when in early December, William Bradford ordered the construction of an eight-foot-high timber wall around the entire plantation for protection. Work on the massive fortification had just been completed when three new ships, also sent by Thomas Weston, appeared in the harbor. Their arrival would trigger the darkest crisis in the Pilgrims' history.

Kathleen Donegan, Literary Critic: Thomas Weston sponsored another competing trading post, north of Plymouth. It was very different from the Pilgrim contingent. They were not there for religious reasons; they did not have a social cohesion; they did not have family structures. They were there for financial reasons, and it was a collection of young men.

Narrator: None of the 60 new colonists were Separatists. They had come to set up what amounted to a rival trading post, and after four months of uneasy cohabitation with the colonists at Plymouth, moved 30 miles up the coast to a place called Wessagussett near a Massachusetts village still reeling from the recent epidemics.

Kathleen Donegan, Literary Critic: And things very, very quickly start deteriorating there. They have terrible relationships with the Natives. They run out of food. The Natives start jeering at them, making fun of them. The people at Wessagusset start trading their clothes for capfuls of corn, they start working for the Indians. And the whole social structure of that trading post just absolutely falls apart.

Narrator: As the new colony disintegrated, more bad news reached Plymouth -- first that the Fortunehad been plundered on her return voyage, leaving the colony for a second straight year with nothing to show for itself, then that a massive Indian uprising, in Virginia, had killed 347 English colonists near Jamestown.

Nick Bunker, Author, Making Haste From Babylon: And the Pilgrims feared that something similar was about to happen to them. And there were clear indications that they were under threat from some parts of the local Native American population.

Narrator: In March 1623, news reached Plymouth that Massasoit himself, their only ally, lay dying, and William Bradford quickly dispatched Edward Winslow to his bedside. Under the Englishmen's skilled care the Wampanoag leader made a rapid recovery, and in return revealed that Plymouth was in the gravest danger from a region wide conspiracy whose aim was to eradicate all English settlements in New England.

Kathleen Donegan, Literary Critic: The Massachusetts have a plan that they want to wipe out the Wessagusset trading post. But they're afraid of retaliation from Plymouth. So the plan is to actually make a coalition, and wipe out both Wessagusset and Plymouth.

William Bradford (Roger Rees): Mr. Weston's colony had by their evil and debauched carriage so exasperated the Indians among them as they plotted their overthrow; and because they knew not how to effect it for fear we would revenge it upon them, they secretly instigated other peoples to conspire against us also, thinking to assault us with their force at home.... but their treachery was discovered unto us and, we went to rescue the lives of our countrymen -- and take vengeance of them for their villainy.

Kathleen Donegan, Literary Critic: Miles Standish and Allerton and Bradford decide to make a preemptive strike. Miles Standish and others go to Wessagusset on the pretense of trade. And they gather many of the Indian men, including two leaders, into the trading post supposedly for trade. Lock the doors, and on a signal, kill these two men with their own knives hanging around their neck.

Bernard Bailyn, Historian: Standish was a war veteran, and the veterans of the Thirty Years' War were brutes, hammerers. And they went up there -- a young Indian boy they hung, and then the rest they stabbed to death and cut off one of their heads, and brought it back and put it on a pole in the middle of Plymouth.

Kathleen Donegan, Literary Critic: Miles Standish decapitates one of them, and brings the head, as a trophy, back to Plymouth where he is greeted with joy. This is Wituwamat. The head is then erected on a pike and placed at the apex of their fort, and it stays there for years.

William Bradford (Roger Rees): By the good Providence of God, we killed seven of the chief of them, and the head of one of them stands still upon our fort for a terror unto others.

Narrator: When word of the attack reached Leiden, John Robinson wrote an anguished letter back to William Bradford.

John Robinson (actor, audio): Concerning the killing of those poor Indians.... oh! how happy a thing had it been, if you had converted some, before you had killed any; besides, where blood is once begun to be shed, it is seldom stanched of a long time after. You will say they deserved it.... but upon what provocations by those heathenish Christians? It is a thing more glorious in men's eyes, than pleasing in God's to be a terror to poor barbarous people. Yours truly loving, John Robinson

Narrator: The bloodshed at Wessagussett was a watershed -- permanently altering the balance of power in the region -- in favor of the Pilgrims and their allies, the Wampanoags. Five months later, William Bradford married a recently arrived 32-year-old widow named Alice Southworth -- in a ceremony attended by the entire community.

Kathleen Donegan, Literary Critic: The Pilgrims usually shun decoration, ornamentation. But when Bradford gets married, people notice one piece of ornament -- a piece of linen soaked in Wituwamat's blood. Visitors to Plymouth commented upon it. It's there in letters. When Massasoit comes with his band to Bradford's wedding, he sees Wituwamat's head on the pike. Although, to Massasoit, it was a signal of the strength of his alliance with Plymouth and Plymouth's willingness to take action against enemies.

Narrator: By 1623, the most immediate existential threats to the colony's survival had started to recede, but other challenges remained, and in the long run these would prove even more intractable.

Bernard Bailyn, Historian: When you trace Bradford's thinking through these years, what strikes me most is the degree to which it was a continuous disappointment. By 1625 -- which is, what, just a few years from the beginning -- he's already complaining that the group is dissipating, that there are troubles, that strangers and Gentiles of all sorts are making trouble.

Narrator: In 1626, a gloom fell over the settlement when news came from Leiden that John Robinson had died the previous winter.

Susan Hardman Moore, Historian: And I think that was a perpetual disappointment to Brewster and to Bradford. They felt the pain of that very clearly that this person who was the most crucial mentor for the whole group -- so instrumental in creating this community -- was never there with them.

Narrator: In 1626, the investors in London -- convinced the colony would never show a profit -- filed for bankruptcy, and disbanded the Merchant Adventurers. Most of the massive debt left behind was assumed by eight of the colony's most stalwart members, who, going forward, would have a monopoly on whatever trade the company might be able to establish -- a prospect that by 1626 looked exceedingly bleak as most people, on both sides of the Atlantic, now assumed the blighted colony would soon fail completely.

But it didn't.

Joyce Chaplin, Historian: Their business model leaned heavily on the idea that America was a place of things of incredible value. Now beaver are not quite as valuable as gold, but it is still a valuable commodity, and the beaver ends up saving them.

Nick Bunker, Author, Making Haste From Babylon: The Pilgrims certainly did try to find beaver skins as soon as they could. But although beaver skins were valuable, the price was relatively low during the early 1620s. It rocketed up later on in 1627-1628. It quadrupled, and the Pilgrims got the benefit of that. But in order to really get furs in sufficient quantities, they needed to get up to Maine. And Edward Winslow was the key character in this, because Winslow had been going up to Maine for several years, particularly the Kennebec Valley in Maine, or the Penobscot Valley in Maine -- river valleys where there are enormous supplies of beaver fur readily available. So everything came together in 1627 and 1628. Price had gone up, Pilgrims had found the furs. The opportunity presented itself, and back came beaver skins in their thousands.

Now once the Pilgrims had been able to deliver beaver skins back to England in sufficient quantities to turn a profit, investors in London saw that if you took this business model the Pilgrims had developed, then you might be able to build a much, much bigger colony -- with not hundreds of colonists, but thousands of colonists. And so they took the Plymouth Colony prototype, and they turned it into something far, far bigger, on a far bigger scale. Which is where you find yourself with the founding of New Boston, in 1630.

Narrator: In the spring of 1630, a ship called the Arabella -- the first of a massive fleet of 17 ships, led by a wealthy Puritan lawyer named John Winthrop, left Yarmouth for the bay of Massachusetts, 60 miles north of Plymouth, bringing 1,000 well-supplied Puritan immigrants. All through the spring and summer the great ships arrived.

By the end of July, a church been established -- the First Church of Boston. By mid-September, the new settlement already had a population of nearly a thousand -- three times larger in 10 weeks -- than the tiny community Plymouth had gathered to itself in 10 years.

Susan Hardman Moore, Historian: The size of the two groups is massively different. The ethos is similar -- they are all Reformed Protestants of a passionate conviction, but the striking difference is the people who go to Boston make an enormous fuss about the fact that they are not separating from the Church of England.

Narrator: In July, Edward Winslow paid a visit to their new sister colony. Whatever their theological differences, he reported, William Bradford could take courage in knowing that the elders of the new colony had been urged to "take advice of them at Plymouth," and to "do nothing to offend them."

After 10 harrowing years, the future of a Puritan New England -- if not a Separatist one -- seemed assured. The Pilgrims' experiment, in that respect at least, had worked.

William Bradford (Roger Rees): Thus out of smalle beginings greater things have been produced by His hand that made all things of nothing, and gives being to all things that are; and as one small candle may light a thousand, so the light here kindled hath shone to many, yea in some sorte to our whole nation; let the glorious name of Jehova have all the praise.

Susan Hardman Moore, Historian: Well, in some ways, of course, it is a success story. Because, completely against the odds, they survived, they put down roots, they established a colony. So in that sense it was a success. The sense in which it is poignantly not a success is, I think for Bradford, the sense that the community he had hoped for didn't materialize in the sweet way that he had hoped it would.

Nathaniel Philbrick, Writer: They wanted to achieve the ultimate spiritual community on Earth -- and that never happened.

Narrator: In 1630, not long after the founding of the colony at Boston, William Bradford, 40 now and beginning his 10th year as governor, sat down to write a history Of Plymouth Plantation, sensing perhaps from the moment the new settlement began how dramatically his own community would be transformed, and determined to leave an account of who his people were, and what had happened to them, and why they mattered.

Kathleen Donegan, Literary Critic: I think, for Bradford, the experiment was not a success. But as a historian writing for posterity, he can tell the story and preserve the meaning of their vision and their implantation. Even as that vision is being dissipated, and not being held by others, he can preserve it in his history.

Bernard Bailyn, Historian: He was aware of what was going on around him, acutely aware of things that were happening. And he was no fool. He knew that when the Puritans started to arrive in 1630 -- 15,000 of them -- the market for agricultural goods was going to boom. Which meant more farms, farther out, fresher ground -- that would further dissipate the religious group. And, even those most committed to its principles are wandering out into farms and outlying districts. The heart of the community was being lost because its integrity was personal -- people living together as a group, praying together and sharing their beliefs.

Nathaniel Philbrick, Writer: And this is a great despair for Bradford. Instead of his little congregation of saints, he has his best friend, Edward Winslow, moving off, forming other towns, such as Duxbury, leaving the mother church.

William Bradford (Roger Rees): Oh, poor Plymouth, how dost thou moan!

Thy children, all, are from thee gone;

And left thou art, in widow's state --

Poor, helpless, sad, and desolate.

Some thou hast had, it is well known,

Who sought thy good before their own.

But times are changed, those days are gone,

And therefore art thou left alone.

To make others rich, thyself art poor;

They are increased out of thy store.

But, being rich, they thee forsake,

Leaving thee poor and desolate.

Susan Hardman Moore, Historian: I wonder, with Bradford. He has had to deal with so much human frailty -- so many human foibles in his life as governor -- that, perhaps, the sense of being a pilgrim bound for heaven, rather than a pilgrim who will reach their new Jerusalem on Earth, is borne in on him very strongly towards the end of his life. I think there may be something of that verse from Hebrews 11 -- "We are pilgrims and strangers in the world" -- comes to his heart.

Bernard Bailyn, Historian: And at the end of his life -- in what to me is especially moving -- he turned to Hebrew. He learned Hebrew. He thought he'd get closer to God in conversation with the sacred Script. Anything to deepen his understanding of what was happening.

William Bradford (Roger Rees): Though I am growne aged, yet I have had a long-

ing desire, to see with my own eyes, something of

that most ancient language, and holy tongue,

in which the Law, and oracles of God were

writ; and in which God, and angels, spake to

the holy patriarks, of old time; and what

names were given to things, from the

creation. And though I cannot attaine

to much herein, yet I am refreshed

to have seen some glimpse here-

of; (as Moses saw the Land

of canan from afarr off) my aime

and desire is, to see how

the words, and phrases

lye in the holy texte;

and to discern some-

what of the same

for my owne

content.

Narrator: He died, on May 9th, 1657, having outlived all his contemporaries, and having served as governor for 31 of the 37 years he had lived in the new world, "lamented," his first biographer, Cotton Mather later said, "by all the colonies of New England, as a common blessing and father to them all."

He was 67 years old. His body was buried on the summit of Burial Hill, near the grave of his mentor, William Brewster -- and in sight of the sand hills of Cape Cod. In the years to come, the world his people had come to in search of a new Jerusalem would be transformed utterly -- with shocking rapidity -- and the Pilgrim experience itself all but carried under, and forgotten.

Within 15 years of his death, there were 70,000 English settlers in 110 towns along the New England coast, and fewer than 20,000 Native Americans left in half a dozen tribes, and only at most 1,000 Wampanoags.

In 1675, Massasoit's own son, Metacom -- called Phillip by the settlers -- helped lead a desperate last-ditch effort to drive the English colonists from their territory before their world was obliterated completely.

Margaret Bruchac, Anthropologist: In the aftermath of King Philip's War, a day of thanksgiving was declared to celebrate that King Philip was now dead, and his head was stuck on a pole in the middle of Plymouth. Which, I think, is why Native people instituted a day of mourning at Thanksgiving. Because had the Plymouth colonists not survived, later colonization might not have happened. Without those coastal settlements that created a toehold and dug in. And once they were there, it was impossible to extricate them.

Narrator: As time went on, the manuscript William Bradford had left to his sons and heirs on his deathbed, was carefully handed down in the family from one generation to the next until a century after his death it found its way into the library of the Old South Church in Boston. It was still there in 1767, when the last royal governor of the colony, Thomas Hutchinson, consulted it for a history he was writing, after which the Revolution came, and the manuscript vanished into thin air.

Kathleen Donegan, Literary Critic: And so Bradford's book was lost. It was taken from there in 1777 by the British, during the Revolutionary War. And people tried to recover it; people tried to find it; people tried to trace it. And nobody knew what had happened to their history -- their great gospel of the founding of the nation.

Narrator: For 80 years following Independence, the missing Bradford text was lamented by scholars in the North, as the shadow of American history lengthened, and as a bitter sectional dispute between North and South intensified -- fought in part over whether the nation's deepest roots lay in slaveholding Virginia or Puritan New England.

Jill Lepore, Historian: There's this tremendous battle in the 19th century between New England historians and Virginia historians about which is the first American settlement -- Jamestown or Plymouth.