Sherwood Davies: I can remember exactly where I was when my mother told me my father had died. We had snow. I was sitting on a step, trying to put on my boots. She came over and said, "Sherwood, your father died last night."

She was very depressed. And I felt concerned for my mother because what she had gone through. My mother's father had tuberculosis and he died when she was 1 year old. Her mother had tuberculosis and was in and out of hospitals. My mother developed tuberculosis, and of course, my father succumbed to tuberculosis. And then I had developed tuberculosis.

It's mind-boggling. I mean, you think of-- you worry about both your mother and your father. But then you say, "Well, what's gonna happen to me?"

Narrator: For centuries, people called it the Captain of Death. By the dawn of the 19th century, the disease had killed one in seven of all people that had ever lived -- more than any other illness.

The ancient Greeks called it "consumption."

Nancy Tomes, Historian: The name consumption came from the emaciation as the fever built and as the coughing continued, the sensation of essentially coughing yourself to death.

Andrea Barrett, Writer: The disease is what used to be called "the wasting disease." You just get thinner and thinner. And so if you look at pictures of people who are dying of the disease, their cheekbones are very prominent. Their eyes seem very large and hollow. All the flesh has wasted off their face and their throat.

Narrator: Victims were racked with hacking, bloody coughs, debilitated by pain in their lungs, and so consumed with fatigue they could barely get out of bed. The end could come quickly or unfold slowly over years of suffering. There was no known cure.

In the early 1800s, consumption struck America with a vengeance, ravaging communities, touching the lives of almost every family.

Sheila Rothman, Author, "Living in the Shadow of Death": No one was spared. Rich, poor, young, old, and no one knew who was going to be attacked, and how long they would live.

Women who had children understood that their children might well become orphans, and that they had to train them how to behave in other people's households. There's a desperation in the stories of, "How can I be sure that when I'm gone my children will be taken care of?" And a lot of talk about death, and you had to train children for dealing with death, and dealing with the death of parents and how to go on and manage.

Narrator: Faced with a deadly and painful disease, tens of thousands of Americans would journey to far-flung parts of the country -- some to the remote wilderness, others to new cities in the South and West -- all in search of an elusive cure.

In 1873, the Adirondack Mountains in New York was one of the most remote regions in the country. That June, a 25-year-old physician arrived from New York City to spend his final days in the woods and lakes that he had loved as a child. Edward Trudeau had just received a crushing diagnosis.

Mary Hotaling, Writer: The doctor tells him that the upper third of one of his lungs is involved in an active tuberculous process. He just stutters his way out the door and stands on the stoop and he says, "The world had gone dark." He just-- he couldn't believe it.

Narrator: Trudeau had no illusions about the disease. Seven years earlier, it had claimed the life of his older brother.

Nancy Tomes, Historian: Trudeau marked his brother's death as one of the turning points in his life. At the time he'd been very close to his brother, and that experience of caring for him in his final days. Imagine then his horror when he finds out he himself develops tuberculosis.

Mary Hotaling, Writer: He was sure he would die. He expected to die and he couldn't believe that, you know, this had happened to him.

Narrator: Trudeau's doctor had told him to spend what time he had left in nature. Physicians of the day believed consumption, as they called it, was hereditary. But they had started to notice that fresh air and outdoor living could sometimes change the course of the illness. Though he could barely walk, Trudeau pursued his passion for hunting by lying down in a canoe padded with balsam branches.

"My hunting blood responded at once," he recalled. "And I forgot all the misery and sickness I had gone through." By the end of the summer, Trudeau had put on 15 pounds. But as soon as he returned to the city, his health deteriorated.

Three years later, nearing death, Trudeau decided to move his wife and two young children to a small Adirondack outpost called Saranac Lake, one of the coldest places in the country.

Even in the dead of winter, Trudeau's health improved. He was becoming convinced the clean mountain air was like medicine for the lungs. "The open-air life," he declared, "has a wonderful effect upon my health."

Nancy Tomes, Historian: Using climate to treat consumption goes all the way back to Greek medicine. In the 19th century, when they started to get more scientific, they also started to try to break that down and think, "Is it cold mountain air? Is it warm dry air that does better for the consumptive?"

Some would say, "Go to the mountains. The air is good there." Others would say, "Go to the beach. Sit in the sun." In fact, physicians advocated all of the above.

Narrator: No region would hold greater lure for consumptives than the newly opened territories of the American West.

Sheila Rothman, Author, "Living in the Shadow of Death": The men who began to explore the West came back with all sorts of stories. That the West was Eden, that the West was health-giving, that people who were thin went out there and became healthy and strong. And so, you began to get this image of the West as a place to go because you would get well. Come West and be cured. Come West and get life. It was a health-giving Eden, this outdoors, beautiful, unsettled part of the country.

Narrator: Starting in the 1840's, health seekers fanned out across the vast plateau between Mississippi and California, living rugged, primitive lives in the wilderness. Together with pioneers and explorers, they played an integral role in settling the West.

Nancy Tomes, Historian: Every western state, you look at the history of their larger cities and you will find that health seekers, many of whom were consumptives, were among the earliest migrants; Young men with consumption, who were moving to cities like Denver or Los Angeles in search of the cure, chasing the cure.

Narrator: In the 1870s, railroad lines began to stretch into the farthest reaches of the country. Jumping on the interest in the climate cure, developers launched an unprecedented campaign to entice people with consumption to settle in stops along the newly laid tracks.

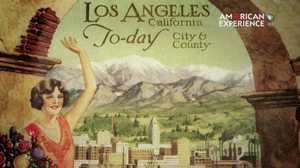

Sheila Rothman, Author, "Living in the Shadow of Death": There were railroad advertisements all over, where they would show a picture of somebody thin and tubercular, and say, "Go West and have health." And there were developers that were building communities, settlements, where they said the air was particularly wonderful, and the climate was particularly great and come here, live in our community, and you will be cured.

Nancy Tomes, Historian: There was no nothing that was too excessive to say. You didn't worry about over-selling the goods. Los Angeles is the healthiest place in the world? Sure. Who's gonna argue? Well, maybe Denver. But they're not around, so you could get away with it then.

Narrator: Tens of thousands of health seekers migrated west. Dozens of new cities sprang up to accommodate the influx: places like Albuquerque, Colorado Springs, and Tucson. The city of Pasadena started as a colony for consumptives from Indiana. Some got better, but many were buried in newly dug cemeteries. Promoters had given little thought to what would happen to their communities if climate was not a cure-all.

In the Adirondacks, Edward Trudeau had started practicing again -- gaining fame as the doctor who saw patients in his hunting clothes. But he suffered one relapse after another, each bringing with it the memory of his brother's death.

Nancy Tomes, Historian: There was the so-called galloping consumption where it would go into the blood stream and you would die very, very quickly. But in other cases it was a long, slow, and agonizing death.

Sheila Rothman, Author, "Living in the Shadow of Death": And no one quite knew why or what made a difference to that. But for the most part, consumption was a disease that could last for 10, 20, 30 years.

Narrator: More and more, Trudeau was becoming preoccupied with finding a cure for consumption -- combing medical journals for the latest information on the illness. He stumbled on a startling revelation in an obscure article written by a German scientist.

Nancy Tomes, Historian: And he reads a copy of Robert Koch's paper, and it is like a religious experience for him. You know, "My eyes were opened. I could hardly believe what I was reading." It was transformative.

Narrator: Robert Koch was one of a handful of European scientists promoting a radical new idea that germs cause disease. Most doctors believed sickness was caused by disturbances in bodily fluids, or from toxic gases or filth, or was inherited. In a complete departure, Koch announced he had found a bacterium, the tubercle bacillus, that he claimed caused tuberculosis. He explained that when he injected the bacteria into a healthy animal, it rapidly developed the disease.

Andrea Cooper, Immunologist: And what Koch did, and this is the basis of modern science, is that he took bacteria, he grew it to purity and then he delivered it and caused disease, and this was the key point. You could isolate the bacterium from the infected person, you could grow it in isolation, and then it would cause disease when it was transmitted again.

Narrator: Koch also described how the bacteria spread. The germs, he said, were expelled through coughing. Someone close-by could inhale the air-borne bacteria into their lungs, where they lodged and caused disease. There was no doubt, he declared, that the disease was highly contagious. His findings were so outside mainstream thinking -- the medical profession simply ignored them.

Nancy Tomes, Historian: The idea of tuberculosis being communicable was so hard to fit with medical tradition, and a lot of the resistance really came out of people who had been looking and thinking for a long time. It just didn't make sense to them.

Narrator: Trudeau, on the other hand, believed he was witnessing the dawn of a new era in medicine and set out to learn how to grow the bacteria himself.

Mary Hotaling, Writer: He was pretty-- an intuitive scientist. He was not a trained scientist at all. When he went to medical school, they didn't have a lab. He never learned how to use a microscope. So, you know, this was a new territory for him.

Narrator: Trudeau set up a rudimentary laboratory in his house in Saranac Lake. Months went by as he struggled to replicate Koch's experiments.

Andrea Cooper, Immunologist: He has no running water in his house. He has no electricity of course, and he had to create his own thermometer, his own incubator, and he would have doors that he would open and close depending on what the temperature was on his homemade thermometer. And he was trying to maintain a 37-degree centigrade environment for the bacteria to grow. So he did that and he had little candles underneath his incubator warming it up, and opening the doors and closing the doors and he was doing this constantly for three weeks to grow the bacteria.

Mary Hotaling, Writer: He is all alone. He has no faculty. He has no help. You know, he is doing it by himself and just out of his own intellectual curiosity.

Narrator: After countless attempts, in 1884, Trudeau became the first American to verify Koch's discovery.

Nancy Tomes, Historian: He takes a sample from his own throat, develops a culture of it, and he can see he himself is carrying this rod-shaped bacillus that Koch has described. So imagine, he was able to test the hypothesis and to show that indeed, there it was.

Narrator: Far away from the power centers of medicine, Trudeau's work went largely unrecognized. For the next decade, Americans continued to go about their lives, unaware of the contagion in their midst.

In 1886, a young writer with consumption arrived at the Los Angeles Railroad Station where most newcomers were greeted by 30-piece bands. Charles Willard was hoping to get well enough to restart his career. Los Angeles was hardly more than a sleepy pueblo town; its streets still unpaved. Yet civic leaders had grand visions for the city and eagerly hawked the dry, temperate climate to East Coast invalids. After working a few odd jobs, Willard landed a position at the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce, where he was put in charge of luring health seekers to California.

Nancy Tomes, Historian: So here's the irony: he himself is still very sick. But there he is, promoting the idea of the climate cure when he has not been cured by it.

Narrator: Willard started a journal called, The Land of Sunshine, and filled it with testimonials to the healing powers of Southern California. He targeted the publication at East Coast readers -- especially those with money.

Nancy Tomes, Historian: Charles Willard did not want to attract the wrong kind of sick people to Los Angeles: people who were not educated, people who were not White Anglo-Saxon Protestants. So there was a real double message there. "Yes, come if you're like me but don't come if you're not."

Narrator: The fine points of Willard's message would quickly get lost in the stampede. Thousands of people with consumption swarmed into the city. A metropolis priding itself on health soon contained a huge population of sick and dying people. One resident described the sounds of the city as a "constant chorus of coughs."

Nancy Tomes, Historian: Try to imagine L.A. as a city of invalids. It really is hard to imagine, but indeed, that was the effect of this kind of boosterism. And when too many of them came, it got to be another kind of problem. Charles Willard succeeded too well.

Narrator: Los Angeles was not unique. Across the West, other cities were also paying a price for their recruiting success.

Sheila Rothman, Author, "Living in the Shadow of Death": And suddenly these cities that saw themselves catering to middle class and upper class people had a large number of poor, sick people all over in their midst, and they were unable to care for them. And they didn't have the resources to care for them, either.

Narrator: In Saranac Lake, Edward Trudeau had watched with alarm as the science of contagion continued to go unheeded. Along with other scientists, he started publishing papers and attending medical conferences to explain the body of evidence. Finally, by the mid 1890s, the medical community was persuaded.

The term "consumption" was dropped in favor of the name that linked it to the bacteria – "tuberculosis" or "TB." Within a decade, Robert Koch would go on to win the Nobel Prize. For patients, the new understanding of the disease would only add to the suffering.

Nancy Tomes, Historian: The sad aspect of this scientific progress is that it made the person with tuberculosis into more of a threat. When you thought consumption ran in families, you couldn't do anything about it. If you got it, you were not to be blamed. Now the individual with tuberculosis was the danger. The more focus there was on person-to-person transmission, the more that stigma, that prejudice, intensified.

Andrea Barrett, Writer: The idea that, although outwardly you may look like a healthy, beautiful 22-year-old woman, you are in fact, vile in some way, contaminated. You know that something awful is happening in your body. And everything around you is sending a signal that you are disgusting in some way; that you have to be separated from healthy people. That seems like the most astonishing psychological burden.

Narrator: Across the West, communities that had once lured health seekers now scrambled to keep them out. Several western states sought to enact laws to stop people with coughs from crossing their borders. Others looked for ways to remove them from populated areas.

Sheila Rothman, Historian: They often set up tent cities on the edge of town. So the sheriff would take them, drop them off in this tent city, and most people were kind of, having to fend for themselves and other people who had tuberculosis, who weren't so sick, would help them. And some charitable people would bring food and some, but they were isolated and indigent, and really, really unwelcome.

Narrator: Even Charles Willard was not immune. When his symptoms became impossible to hide, he also became a target. After his home accidently burned to the ground, no one would rent him a place to live.

In cities across the country, public officials began to call for government intervention. Health departments primarily concerned with preventing diseases carried in the water supply now had to confront a deadly illness spread through the most casual of contact.

Nancy Tomes, Historian: Public health officials felt they had to conduct a massive national campaign to bring the news to everyone in the United States. In fact, it's the first mass public health campaign in American history. There's nothing like it before. The campaign to teach every single American that they needed to be careful about how they coughed and sneezed because you could never tell who was sick and who wasn't.

Sheila Rothman, Historian: And they pass these brochures out so that people could understand that spitting could spread the disease. Coughing without a handkerchief could spread the disease. They promoted the use of Kleenex. I mean, this is how Kleenex came about.

Nancy Tomes, Historian: Women's hemlines start to go up after 1900. It was so you could get your skirts out of the dirt and not carry home a load of germs into your house. Men's style of wearing beards changed. The anti-TB handouts would say, "Get rid of your whiskers," because you don't wanna kiss the baby or kiss your wife and give them tuberculosis with your beard germs.

Narrator: Crowded neighborhoods transformed as parks and playgrounds were built to provide urban dwellers with islands of fresh air. New Yorkers began to call Central Park the "lungs of the city."

By the early decades of the 20th century, improved hygiene started bringing the overall cases of TB down. But, in poor, crowded neighborhoods, the figures continued to climb. In some cities, immigrants were twice as likely to die of the disease than their more affluent neighbors. For African-Americans, the death rate was three to four times higher.

Sheila Rothman, Historian: And suddenly you have a new understanding of why it is a disease of the poor and the immigrant. They are living in places without ventilation. They are working together in crowded sweatshops. So it kind of feeds on itself: a new understanding of the disease, and the whole beginnings of policies to try to lessen the impact and reduce the spread of the disease.

Narrator: Public health officials began to call for improving the lives of the poorest Americans: better housing and working conditions, reduced working hours, and child labor laws.

Yet the anti-TB campaign gave government officials unprecedented power to police the sick. Health inspectors were instructed to monitor people's movements, inspect their homes, or commit them to ill-equipped public institutions, often against their will.

Nancy Tomes, Historian: The pressure from public health officials to segregate the very sick fell most heavily on working class, poor Americans, immigrant Americans. They did not go knocking on doors on 5th Avenue asking, "Do you have any consumptives in the house?"

There was a sense, if you were wealthy, you were gonna be allowed to manage your illness however you wanted to. It was the poorer people who really felt the pressure from public heath officials to make their sick relatives leave the home and go into one of these institutional facilities.

Narrator: "Sanitary measures are sometimes autocratic," declared a prominent health official. "We are prepared to enforce measures which might seem radical if they were not designed for the public good."

Nancy Tomes, Historian: It's an area of public health practice where, increasingly, the need of the community to be protected from the illness starts to trump the individual rights of the patient. When people say, "I don't want to be taken away," their right to resist that is overridden in the name of public health.

Andrea Barrett, Writer: How do we ever live with a contagion in our midst? Someone is sick among us, that person needs care and help, that person is also contagious and can give us what they have. What is the balance between taking care of the community and taking care of the person? That question's always with us, and it almost never has a good answer.

Narrator: With each passing year, hundred of thousands of Americans with tuberculosis scrambled to find medical care. Hospitals were overwhelmed. To cope with the flood of patients, New York City's Bellevue Hospital transformed ferry barges into makeshift wards.

Andrea Barrett, Writer: There was no room to put people who had tuberculosis. So this was a one way to separate out contagious people was to take all the consumptives from a local neighborhood and put them onto these day camps. And they'd spend the whole day on their little chairs in the barge moored on the river. It was just a way of keeping them out of their rooms and their rooming houses and out of their workplaces.

Sheila Rothman, Historian: Some of the hospitals would only take people who were in their first attack because they didn't want to take people who were dying. They weren't in the business of caring for the dying. So sometimes you had to change your name, pretend you were someone different, go to a different hospital. It became a game of trying to figure out how to survive and how to make it when you really had no resources.

Narrator: Years earlier, Edward Trudeau told friends that he wished that more people could find relief, as he had done, in the cool, fresh climate of the Adirondacks. He had begun reading about European sanatoriums -- facilities built in the countryside that provided long-term care for tuberculosis patients.

Andrea Cooper, Immunologist: Edward Trudeau was familiar with the treatments that were occurring in Europe at that time, and there was a growing idea that one should take people who had tuberculosis and take them into an environment that was perhaps different from the environment they were in. And one of the ideas that they had was that they would go out into the country, they would be resting, they would be given good food, and they would be exposed to the sunlight.

Nancy Tomes, Historian: So the idea of the sanatorium was to create a place where people who had been infected could rally their body's healing forces to throw it off. We, today, talk about the immune system. They didn't use that language but it's clearly the phenomena that they were describing.

Narrator: Trudeau was determined to build the first tuberculosis sanatorium in the United States. He had grown friendly with wealthy TB patients from the city and now urged them to open their wallets to help create a treatment facility for people of modest means.

Mary Hotaling, Writer: The people who came originally were wealthy patients. They were the people who could afford to take a difficult trip through the wilderness to get here, and then could hire a place to stay in a hotel or rent a house or build a house. But Trudeau felt there should be a place for people who were not so well off. That's why he founded the sanatorium.

Narrator: By 1900, Trudeau's sanatorium would grow into a sprawling campus of 22 buildings including a church and a research laboratory. News of its success spread so quickly, medical professionals flocked to Saranac Lake to see it for themselves.

Trudeau ignited a movement. Over the next decade, hundreds of sanatoriums would spring up in every part of the country; many of them set up by charity or religious groups. State governments opened huge complexes for people who couldn't afford care in private institutions. Many facilities were segregated by race. African Americans barred from whites-only sanatoriums helped start their own.

In the first decades of the 20th century, one out of every 170 Americans lived in a sanatorium, some for many years. It was a life of exile.

Whitney Seymour, Jr.: I began to realize that I was getting extremely tired and then started coughing up phlegm, and so I made an appointment to go see the family doctor. And he saw the tubular bacilli right away and he said, "Young man, you have tuberculosis and you got to go to Trudeau."

He didn't fool around, saying, "You can think about it." He was very adamant. And all of a sudden, it was all over, and I was now suddenly being told to, "Get yourself on a train and get up to the mountains and start curing. You're a very sick young man."

Sheila Rothman, Historian: People often left in the middle of the night. They left without telling people. They just quit their jobs or they just left. Sometimes they were trying to protect their families, and sometimes the families were trying to protect themselves.

Narrator: For some, the sanatorium held the promise of cure. For others, it was the place to go to die.

Whitney Seymour, Jr.: The white-coated doctors coming in and looking down, saying "Hmm… ah-ha," and walking out. And, so I would figure these guys were measuring me for a coffin.

I was left there in a hospital bed and I really was overwhelmed by a sense of despair. I really thought that I was about to die.

John Stoeckle: The hardest time was accepting that I was there and maintaining hope that I would get better and being optimistic. So, it was a separation from your usual life that really was very hard to take. You are really basically lonely.

Joanne Curtis: They never told me how long I would be at the hospital, and I never asked. Don't ask me why. I never cried, I never asked. I just took one day at a time, kept my sense of humor, and that was it. That was my armament. That was it.

Narrator: Entering a sanatorium required complete submission. Physicians and nurses regulated every moment of the day -- measuring patients' progress towards health by testing for bacteria in their phlegm and x-raying their chests.

Trudeau believed TB patients needed to be well fed, and insisted they consume at least six glasses of milk and six raw eggs a day. And, he ordered them to rest.

Andrea Barrett, Writer: When people first came to a sanatorium, many were put on 24-hour rest. They were put directly to bed. They stayed there. All their meals were brought to bed on trays. They were not allowed to even get out to go to the bathroom. They had bedpans.

Joanne Curtis: Class One was bed rest. Class Two, bathroom privileges only. Three, I could walk around a lot. By the time I got to Two, I was restless. I got yelled at by my doctor because I would be ripping up and down the hallway. And he said, "Young lady aren't you in class Two? You're supposed to just have bathroom privileges." And I said, "Oh, I didn't know that." He said, "Yes, you did. Go back to your bed." So that's-- yes, I did.

Narrator: For Trudeau, where his patients rested was as significant as how long. He was convinced that fresh air was the single most important treatment for a diseased lung. He instructed his patients to lie outdoors on reclining chairs, day and night, regardless of the weather.

Sherwood Davies: I'd sleep at night on the porch, get fresh air. That's what they called it. When it was 10-below it was a little more than fresh air. Damn cold weather. But I would have an electric blanket and I'd have about four or five other blankets over the electric blanket, and then a rubber sheet over that. And then a wool cap over my ears.

Whitney Seymour, Jr.: The cure cottage that I was assigned to was not an outdoor cure cottage but glassed in, that is, I slept outside the building but you could see nature all around you. And the thing that I still remember was the sunlight bouncing off Mount Marcy and then streaming in through these windows and making it just very cheerful and hopeful. And make you begin to think, "Gee, it'd be nice to be out there."

Narrator: With no treatment available other than rest and fresh air, tuberculosis sufferers everywhere strived to imitate Trudeau's method. Across the country people added porches to their homes. When that wasn't possible, they simply made do.

Andrea Barrett, Writer: There were tents on the roofs of some tenement buildings all over Brooklyn. A cure chair inside and someone wrapped in all their hats and clothes. And then there were also tents that could be inserted into a window. So that if you were in your apartment house, your legs would be inside the house and the white tent would stick out the window and somehow the fresh air was supposed to come into you, just from your head sticking out the window.

Narrator: For all they had surrendered when they entered the sanatorium, patients also found a certain freedom. Unburdened from the fear of infecting others, they sought comfort in each other's company.

Sheila Rothman, Historian: In these situations there was a great deal of gossip. Everybody gossiped about everybody else. Who's talking to who, who's trying to run away and drink, who left, and also, who died.

Andrea Barrett, Writer: Even if you're out on the porch and it's a sunny day and you're having conversation with a friend, or flirting with someone, just a few beds or a few rooms away someone else is coughing horribly or having a horrible hemorrhage that's being cleaned up within your sight, or a body's being taken down the corridor on a gurney. I think the presence of death had to be with you virtually every minute of every day.

Sherwood Davies: I remember two young ladies, very personable, and I was in my teenage years, and these were attractive young girls and I got to know them. Ruth Templeton and Mary Patterson. And, within four to six months of their arrival, both of them had died which, it troubled me to no end. Two young ladies like that that developed the disease. I still remember their names to this day. It's… it was very unfortunate.

Narrator: Trudeau's own studies revealed that only a third of his patients got well. He stood by the bedside of hundreds of dying patients, but the hardest death to bear was that of his own daughter. Charlotte died of tuberculosis at the age of 16.

The doctor was rarely free of symptoms himself, frequently having to stop work to take the rest cure. When Edward Trudeau died in 1915 after a 40-year struggle with tuberculosis, a miracle cure was still a dream.

Newsreel Announcer (archival): Through mass production methods, America is continually increasing its output of penicillin, the new drug that affects almost miraculous cures. The liquid charged with penicillin is poured from the bottles, turned into a powder, it is ready for use.

Narrator: In the early 1940's the discovery of penicillin revolutionized the treatment of infectious diseases. Derived from a mold, the first antibiotic cured a host of infections -- but not tuberculosis.

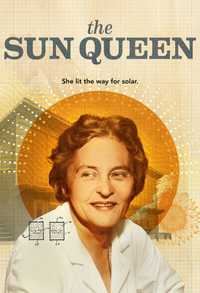

A microbiologist at Rutgers University believed he knew where to look for an antibiotic that would -- literally beneath people's feet. Selman Waksman was one of the few people in the country who understood the true nature of soil. Early in his career, he had written a definitive work on the microscopic organisms that live in the ground -- describing the earth in an ordinary garden as a killing field where warrior microbes fight each other for supremacy.

His previous work pointed to the Streptomyces: strange organisms, half bacteria and half fungi -- responsible for the sweet odor of earth after a light rain. But there are over 500 different species. Finding one that could kill harmful bacteria without toxic side effects would prove to be extraordinarily difficult.

Peter Pringle, Writer: It was unbelievably time consuming, and if you like boring, and you could look all day long and see absolutely nothing happening through your microscope. So you go to a different soil patch, maybe you go closer to the horse's stables because the bacteria that you really want are those which feed on horse dung rather than dried leaves. So it's a huge hit and miss affair.

Narrator: In late summer 1943, Waksman assigned the research project to Albert Schatz, an energetic 23-year-old graduate student. The hunt for antibiotics captured Schatz's imagination. He would often spend 18-hours a day peering into his microscope looking for the telltale sign of an antibiotic.

In what was known as "the streak test," Schatz placed common bacteria in a petri dish, swiping a strain of Streptomyces down the middle. If the strain were potent enough, it would create a dead zone around it.

Peter Pringle, Writer: It's a battlefield, and the clear zone gets bigger and bigger and eventually, you're watching it destroy your harmful bacteria and you say, "Whoopee, I've got something!"

Narrator: Three months in, Schatz stumbled on a variety that appeared quite powerful. On October 19th, he sealed a test tube containing the promising batch and gave it to his mother as a memento of his achievement. Schatz was eager to test the new antibiotic against tuberculosis, even given the risk.

Vivian Schatz, Wife: That laboratory was not set up for a dangerous germ like tuberculosis. So there were a couple of basement windows, and some stools to sit on, and that was it. It was very sparse. And not what you would expect where people would be working with a very virulent organism.

Peter Pringle, Writer: And the equipment is very primitive. It's not exactly clean. There was none of the stuff that you see today of, you know, enclosed labs where people are manipulating their Petri dishes with mechanical arms. It was nothing like that.

Narrator: Schatz talked Waksman into letting him proceed.

Vivian Schatz, Wife: He slept in the laboratory because he had to add fluid to the glass containers that were being distilled, and when the liquid in a container got to a certain level he had to add more liquid. So it was very, very, tiring, hard work.

Narrator: Within weeks, Schatz would witness one of most dramatic events ever seen under a microscope -- the destruction of the tubercle bacillus. Waksman and Schatz named the antibiotic, Streptomycin. The following spring, Waksman sent the drug to the Mayo Clinic for testing with patients. Starting in November of 1944, researchers gave five courses of streptomycin to a 21-year-old woman dying of tuberculosis. Within days, the infection in her lungs began to disappear. A few months later, she was discharged from the hospital.

Nancy Tomes, Historian: So with Streptomycin, for the first time in human history, there's a magic bullet. There's a drug you can give to people that is going to make the majority of them far, far better. You can cure tuberculosis.

Sheila Rothman, Historian: I mean it was unbelievable. A disease that had plagued humanity for 3,000 years was suddenly able to be cured.

Sherwood Davies: The Medical Director assembled all the patients and all the staff and announced this drug that they had just discovered. And what a reaction from the patients there. I mean, you could see the smiles on their face. Well, it was indescribable.

Narrator: The euphoria would not last. Within months of treatment, many patients began to relapse. Scientists would come to understand that Streptomycin does not destroy all the bacteria in the body, and the organisms that do survive grow stronger and more resistant to the drug.

Andrea Cooper, Immunologist: Suddenly the drug was not being effective when it had been so effective so quickly. And so they understood very rapidly that it was the resistance was occurring. And so they needed to develop further drugs.

Narrator: By the late 1940s, two additional drugs were added to Streptomycin. The drug cocktail, properly administered, was far more effective.

Andrea Cooper, Immunologist: And with tuberculosis, it's clear. You need a combination of drugs. So the bacteria has to combat two or three attacks at once rather than a simple one attack. It can cope with one, it can't cope with two, and it can't cope even less well with three. And then when we take the antibiotics, we need to take them consistently, correctly, not over do it, and not under do it because then you will facilitate the development of drug resistance.

Narrator: Before antibiotics, half of all people with active TB could expect to die within five years. By 1950, most were getting well and going on to live normal, healthy lives. As cures mounted, the sanatoriums began to close. Many were demolished. A few became ski resorts or hotels.

Whitney Seymour, Jr.: Almost from the very beginning, when I was in the infirmary, these young doctors came by and say, "We're gonna experiment with these new drugs." And so, it was then quite obvious that Trudeau was gonna close in a few weeks. And we're instructed to go find apartments in town so we could continue to get well. And all of a sudden I realized, I can overcome it and live a long, healthy, hardworking life.

Sherwood Davies: I had looked back at the family's history of tuberculosis and said how lucky I was. And when they said I was essentially cured, I was elated. I wasn't thinking so much of a big relief on my part, but what my mother had gone through because here she was, she had dealt with her mother, she had dealt with my father, and now she had to deal with me.

I think the proudest thing in her life was when she came to my college graduation. And she-- her life was fulfilled.

Narrator: In November 1954, a former professional baseball player named Larry Doyle ate his last meal at the head of a long table at the Trudeau Sanatorium. He had been a patient for 12 years. After lunch, he walked out the front door and strolled through the snowy streets of Saranac Lake. He was the last tuberculosis patient to leave Trudeau.

Slate: In the 1980s, tuberculosis in the U.S. spiked as a result of the AIDS epidemic.

Since then, drug-resistant TB has become more common.

There are nearly 10,000 TB cases in the U.S. and nine million worldwide.