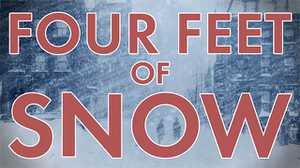

Narrator: On the morning of Monday, March 12, 1888, the east coast of the United States from Virginia to Maine awoke to the severe blizzard in American history. Four feet of snow fell from the skies and fierce winds created snowdrifts up to fifty feet high. With over 400 dead and citizens left scared and angry, the blizzard underlined a transportation crisis that had been escalating for decades. In a booming economy, cities were flooded with thousands of immigrants and rural Americans seeking opportunity in a newly mechanized world.

Clifton Hood, Historian: The problem is that everybody’s crowded into a fairly small area. The available modes of transportation are slow and cumbersome. The city is growing but the transit system isn’t growing with it.

Narrator: America was in danger of choking on its own progress. In no place was the problem more overwhelming than the nation’s most congested city, Boston, where nearly 400,000 people packed into a downtown of less than a square mile.

Stephen Puleo, Writer: There are almost 8,000 horses in Boston pulling the trolley railways around the city. It is a cacophony of noise, dust, horse manure, smells, in the downtown area, extremely congested.

Narrator: As America struggled to address its transportation crisis, leaders in Boston pursued a radical solution. But their race to build the nation’s first subway would clash against political gridlock, selfish businessmen, and a terrified citizenry.

Brian Cudahy, Writer: The idea of a subway in Boston was an enormous risk. It was a breathtaking jump into the unknown and that can’t be underestimated. This was a jump into the unknown.

Narrator: In early 1882, a young American naval officer on leave walked the crowded streets of London. Frank Sprague, just twenty-four years old, had heard of the world’s first subway, the London Underground. Hailed as an engineering marvel, he wanted to see it for himself. As he descended from the street down the steps into darkness, he could hear the roar of the trains thundering through the tunnels below.

Doug Most, Author, The Race Underground: Boston, New York and the Incredible Rivalry that Built America’s First Subway: In 1863 when the London Underground opened it was a coal-powered steam engine running underground. The subway coming through London’s tubes was spewing dark soot, and smoke, and sparks into the air. One journalist who rode on the London subway compared it to standing next to someone blowing cigar smoke in your face for the entire time. It was just a miserable riding experience.

Narrator: Sprague, an aspiring inventor, thought there had to be a better way. It was the age of electrical invention — the light bulb, the telephone, the dynamo — and Sprague, having studied electricity at the Naval Academy, was full of ideas.

Frederick Dalzell, Historian: Frank Julian Sprague is a driven person. A colleague once said of Frank Sprague, “It seems as though he had wires coiling and uncoiling inside of him.” He was constantly in motion.

Narrator: Sprague had spent a year at sea with the Navy, inventing in his head.

Frederick Dalzell, Historian: It’s very cerebral. He keeps a notebook. And in the notebook he draws all these schematics, all these blueprints, all these drawings; he sketches out these ideas. There are armatures. There are new improved versions of arc lighting. There are electric motors. And the notebook is — you can almost feel the energy — it vibrates, it really does. He senses that this new force, it seems almost limitless in its potential. And above all he senses that electricity can move things if people can learn how to harness it and put it to work in the form of electric motors.

Narrator: With his frequent trips underground while in London, Sprague came up with a revolutionary plan. He sketched out a subway system where electricity would supply the power. It would be conducted to the trains from an overhead source, through a motor, and then back to the rails below.

Sprague was so confident of his idea that he immediately applied for a patent.

Rosalind Williams, Historian: In this era, late 19th century, electricity is magic and it has a magical set of effects. But also there’s a great deal of anxiety that went with the magic of it. It’s invisible, it’s very powerful, it can kill you but you can’t see it, so there’s all sorts of, of anxieties. You’ve got potency and invisibility. You can argue the science but the fear is there.

Narrator: As cities across America were being wired for electricity, newspapers reported on horrific accidents. Sprague’s vision for a subway in America depended on the public overcoming its fear of this unsettling power source. Convincing Americans that traveling underground was a good idea would be an even more daunting challenge.

Brian Cudahy, Writer: There was an enormous fear of going underground in this restricted environment. One of the health considerations at the turn of the century was tuberculosis and pulmonary disease. And people were just concerned that living, traveling in this underground environment could be very detrimental to health.

Rosalind Williams, Historian: The underground is scary for two reasons. One is the association with death. We just know that in the underworld we are getting closer to another realm. But the underworld is also scary because it’s not friendly to human life, never was, never will be. Everything you do down there has to be done with engineering to enable humans to survive. You put those two together and you can see why people are afraid of the underworld.

Narrator: By 1883, Frank Sprague had landed what he thought was his dream job when he was recruited by the famed inventor Thomas Edison. At Edison’s lab in New Jersey Sprague hoped to begin work on electric motors and railways. Edison had other plans, assigning him to his Construction Department to work on central power stations for his vast lighting systems.

Doug Most, Author, The Race Underground: Boston, New York and the Incredible Rivalry that Built America’s First Subway: What Sprague would often do is he would go on these assignments for Thomas Edison, but at night, and on weekends, and in any waking moment he had when he was not doing something for Thomas Edison he was working on his motor.

Narrator: Eventually, Edison did ask Sprague to work on motors for his company. But the young engineer knew that anything he designed would have Edison’s name on it. In April of 1884, less than a year after joining Edison’s team, Sprague was forced to decide between staying on with Edison and risk giving up ownership of his motor ideas, or venture out on his own.

Frederick Dalzell, Historian: Sprague knows that if he develops a motor at Menlo Park, even if Edison has been only peripherally involved, the result will be hailed as Edison’s latest, greatest invention. That’s not what Sprague wants at all.

Narrator: Sprague resigned. Within months was displaying a variety of his groundbreaking electric motors at the International Electrical Exhibition in Philadelphia.

Frederick Dalzell, Historian: Sprague’s motor’s different from any other electric motor at the time because it was what Sprague called a self-regulated motor. And what that meant was it was able to bear different size loads at the same speed. So it could carry ten pounds, or twenty pounds, or thirty pounds and lift it at the same speed. It made Sprague’s electric motors much more attractive for potential users, particularly in fields like industry where you’re powering crude elevators, or you’re powering railways.

Narrator: Even his former boss was impressed. “His is the only true motor,” Edison told a reporter. Such high praise from the world-famous Edison was invaluable in giving Sprague an edge over his competitors. One month after the Philadelphia exhibition, he launched the Sprague Electric Railway & Motor Company and began promoting his ideas across the country. His potential customers included transit moguls in America’s largest and most congested cities.

Doug Most, Author, The Race Underground: Boston, New York and the Incredible Rivalry that Built America’s First Subway: Frank Sprague knew that in order for a motor to succeed, in order for his business to succeed he was gonna need a big client. He was gonna need someone to take a chance on him.

Narrator: In 1886, in a narrow alleyway between two brick buildings off East Twenty-fourth Street in Manhattan, Sprague nervously attached his electric motors to a railroad flatcar. Sprague’s potential investor that day was one of the top ten richest men in America. Jay Gould owned more railroad track and telegraph lines than anyone in the country. He also had a controlling interest in the Manhattan Elevated Railway Company and was in a search of a new way to power his trains. If Sprague convinced Gould that his electric motor was the answer, it would change the young engineer’s life.

Clifton Hood, Historian: One of the ways you made money in the United States in the Gilded Age was to invest in new technology. That’s true of steel. It’s true of oil. And it’s also true of mass transit. So who’s making decisions about where the transit lines go, when they’re built, what kind of technology they have? By and large it’s private industrialists. It’s capitalists. It’s the people who have a lot of money.

Narrator: Sprague positioned Gould at the front of the flatbed car, hoping the vantage point would provide a more thrilling ride.

Doug Most, Author, The Race Underground: Boston, New York and the Incredible Rivalry that Built America’s First Subway: Sprague pushed the lever to move the car forward. In his zeal and confidence to show Gould just how smooth his motor could power this train car he probably became a little overzealous and pushed his motor too hard. And what happened was as Jay Gould was standing on this streetcar a burst of sparks shot out right by Gould’s legs.

Brian Cudahy, Writer: And Jay Gould went running off and said, “Never on my railway will we use this crazy new form of energy.” Here’s Gould, who would be perfectly willing to take million dollar risks in building railways across the United States, but electricity was such a new thing that when there was an explosion and a flash on the streetcar it scared Gould to death. And Gould wanted nothing to do with Sprague.

Narrator: By the end of 1886 Frank Sprague was running out of money to conduct his tests and had to face the reality that no one was interested in his electric motor. What he didn’t know was that two hundred miles to the north his ideas had caught the attention of one of the biggest transportation kings in the country.

Narrator: On March 4, 1887 Henry Whitney, president of the newly formed West End Street Railway Company, arrived at the Massachusetts State House in Boston. Years earlier, Whitney began purchasing tracts of land along Beacon Street, a carriage road in the wealthy suburb of Brookline that led straight into the downtown. Whitney had invested his fortune in real estate and owned almost four million square feet of land. He believed if transit lines could reach the desirable suburb, his property values would skyrocket.

Mark Gelfand, Historian: The development of Boston, as in most other cities, was largely in private hands. And these developers of large tracts of property recognized that their profitability depends upon making these areas accessible to the downtown area. And so there is a direct and crucial link between development and transportation.

Narrator: Boston was bursting at the seams. Its population had more than doubled since the Civil War, to nearly 450,000. The city’s horse-drawn street railways were overwhelmed, carrying more than 91 million passengers a year.

Asha Weinstein Agrawal, Historian: The streets were absolutely packed every day with all these hundreds of thousands of people were pouring into the downtown. So you really had just this incredible mass of people in a very small area.

Narrator: Seven street railway companies aggressively competed for passengers in Boston’s downtown.

Doug Most, Author, The Race Underground: Boston, New York and the Incredible Rivalry that Built America’s First Subway: Each of them has their own routes and fares. And it was this crazy, convoluted system. If you wanted a streetcar in 1887 you would raise your hand and all these different cars might race to pick you up.

Clifton Hood, Historian: The term “transit system” implies that there’s a coherence. I think it implies that there is a kind of public service. It implies that there is a technological efficiency. And I don’t think that’s how most Americans and certainly not most transit operators view this. It’s the profit motive that determines the quality and the amount of service.

Narrator: At the State House, Whitney boldly proposed the consolidation of all seven street railway companies into one large transit system, which he would control. His argument was for efficiency, but he knew that by controlling all the lines, he would be positioned to do as he pleased with his suburban expansion.

Asha Weinstein Agrawal, Historian: I think there was actually a lot of support in many ways from the larger public. You might think, “Oh, a monopoly. People aren’t gonna like this,” but there was a sense that it was very inefficient to have so many different street railway companies that they were competing for passengers.

Narrator: Whitney suggested that to rid the congestion strangling its streets, it was necessary to construct tunnels beneath the city.

Doug Most, Author, The Race Underground: Boston, New York and the Incredible Rivalry that Built America’s First Subway: It caught everyone by surprise this idea of a tunnel. It was exciting, it was scary, it was a big deal for Henry Whitney to suggest that. But he threw out a third thing, which really caught people’s attention, which was acknowledging that the horse had seen its day and that perhaps the electric motor was in fact the future of urban transit and the way that Boston needed to go. And he put himself on the line with this idea that the electric motor, which until that point still was not a really proven technology but something that he had seen, and believed in, and felt like, it could work.

Narrator: The Massachusetts General Court granted Whitney the right to consolidate Boston’s streetcars and the permission to build a subway if he desired. His West End Street Railway Company now controlled 1,700 street railway cars and 200 miles of track, making it the largest transit system in the world — bigger than anything in London, Chicago, or New York. Whitney’s biggest challenge remained: finding a way to replace the 8,400 horses that were grinding Boston’s streets to a halt.

In the summer of 1887 Frank Sprague was desperate. He needed to find a place to demonstrate his electric railway on a large scale. He found it in an unlikely place. The Richmond Union Passenger Railway Company asked Sprague to build a complete electric railway system: 12 miles of track, a 375-horsepower electrical plant, and overhead lines to carry electric current to forty cars and eighty motors. He had ninety days to construct it and wouldn’t get paid a dime until the system was up and running. Experts said it couldn’t be done: the Richmond hills were too steep and Sprague’s motor wasn’t powerful enough.

Frederick Dalzell, Historian: People have tried to set up a railway system using the existing technologies of the period — horse-drawn railways. But Richmond is a horse killer. That’s an awful way to put it but, the topography, the landscape, it’s just brutal to try and make this thing work using horses.

Narrator: It was a massive risk. But Sprague was forced to bet his company on the near impossible project. “Failure in Richmond,” Sprague said, “meant blasted hopes and financial ruin.”

Doug Most, Author, The Race Underground: Boston, New York and the Incredible Rivalry that Built America’s First Subway: It was a contract that no one in their right mind would ever sign, essentially being asked to build this on spec. But Sprague at that point was close to desperate. He needed money. His experiment with Jay Gould had failed. He did not have an investor. He needed his, he needed his project to succeed and he needed it to succeed soon.

Frederick Dalzell, Historian: Unfortunately, shortly after he signs the contract he is stricken with typhoid fever. And it takes over a month of convalescence to really bring himself back into working shape. When he does visit Richmond he is profoundly discouraged. The conditions are much more challenging than he had imagined. The first set of rails that’s laid down is completely unsuitable. The whole thing looks like a disaster.

Narrator: Sprague’s crew spent weeks rebuilding the entire system of tracks. To help prevent the motors from disengaging over the bumpy terrain, Sprague would test out his innovative wheelbarrow mount, a design he had been working on for years.

Brian Cudahy, Writer: What was unique to Sprague was his ability to design a mounting, so that the motor could move up and down while it remained meshed with the gear on the axle. It was a significant breakthrough.

Narrator: He was confident the motors would stay on the streetcars, but he did not know if they could scale Richmond’s steep hills. Sprague set up a trial run at night, hoping no one would see a potentially embarrassing failure.

Frederick Dalzell, Historian: The car scales the hill and comes down the other side, makes a turn, climbs another hill that’s even steeper. Sprague has no idea what’s gonna happen. The car makes it to the top. And as it does the engine locks up. Sprague realizes what’s happened. He’s actually burned out the motor.

Narrator: Sprague needed more power. With the ninety-day deadline looming, he scrambled to re-design the motors with larger gears and have them fabricated by a machinist in Rhode Island. When they finally arrived, Sprague got the streetcars running without any burnouts.

As the weeks slipped away, Sprague and his engineers worked round-the-clock, tackling one technical problem after another. “I am completely overwhelmed with work,” Sprague wrote to a friend, “so much so that I hardly know whether I stand on my head or my heels.”

Finally, on May 15, 1888, after investing $75,000 of his own, the Richmond system was up and running.

Frederick Dalzell, Historian: Richmond is a real turning point. Sprague was able, on the basis of Richmond’s performance, to show people real data. This is what the railway system in Richmond earned before it was electrified. This is what it earned after. This is how much money you can make.

Narrator: The day after the Richmond contract terms were satisfied, Frank Sprague wrote to Henry Whitney in Boston. “We are ready to run commercially,” the young engineer reported, hoping to convince the world’s largest streetcar owner to buy in. Whitney boarded a train and headed to Richmond, his head full of questions and doubt.

Brian Cudahy, Writer: Whitney had misgivings when he got to Richmond. This is a rural southern city without the concentration of business, without the narrow streets that Boston had.

Doug Most, Author, The Race Underground: Boston, New York and the Incredible Rivalry that Built America’s First Subway: At about midnight Whitney’s brought to the bottom of a steep hill. And at the bottom of this hill Frank Sprague has lined up 22 streetcars.

Frederick Dalzell, Historian: He’s never tried this before. He talks to the electrician at the power plant and he says, “Give her all you’ve got and don’t let up.” The lights actually get lower because the strain on the system is so, is so intense.

Brian Cudahy, Writer: And slowly each one started up, one right after the other. The power station didn’t blow out. Fuses didn’t blow. The cars could all run at the same time.

Narrator: Sprague’s brash demonstration and risk had paid off. Whitney was impressed and headed back to Boston with the intention of electrifying his entire system of streetcars.

Brian Cudahy, Writer: There’s certainly no doubt that his demonstration to Whitney and its success was an important turning point in the history of mass transit in America, and in the history of mass transit in the world.

Clifton Hood, Historian: There’s a search for a practical mechanical mode of transportation. And what Frank Sprague’s invention means is that we’ve ended that search; that we’ve found it. It’s a big distance from this little railway in Virginia to the Boston subway but you can envision going there now.

Narrator: Upon his return from Richmond, Henry Whitney immediately contracted Sprague to supply thirty electric cars to his West End Street Railway Company. Whitney envisioned passengers gliding smoothly along Beacon Street into and out of downtown Boston, but it would not happen easily.

Key to Sprague’s innovation were the overhead wires supplying power to the streetcars. Boston’s city leaders, however, would not allow them to be installed.

Brian Cudahy, Writer: Electricity was seen as a very, very dangerous form of energy particularly when wires would break and they’d fall to the ground, people would touch them and be electrocuted. So people had to be convinced that electric powered streetcars were a safe way to travel.

Narrator: To persuade city officials Whitney arranged for a test ride. With Sprague driving, the electric streetcar sped up to 25 miles per hour, propelling the lawmakers faster than they had ever traveled before. Exhilarated by the ride, Boston granted Whitney permission to install the overhead wires.

He then moved forward with plans to build a central power station in Boston’s South End that would be the largest in the world. With its chimney 250 feet high, it was the tallest structure in Boston, thirty feet higher than the Bunker Hill monument.

Doug Most, Author, The Race Underground: Boston, New York and the Incredible Rivalry that Built America’s First Subway: Just like Frank Sprague was a big thinker Henry Whitney had this vision and this passion. He really believed he could be a change agent for how people moved about and how the transit system operated. He made people re-think how their city could look and could function.

Narrator: Electrification commenced rapidly and profits were rolling in for the West End Street Railway Company. In just five years, more than 80% of the system was electrified. Despite the monetary success of the West End, the electric trolleys proved so popular, the streets were clogged worse than ever.

Brian Cudahy, Writer: When Whitney returned from Richmond and signed a contract with Sprague, to electrify the West End Street Railway, it wasn’t the end of a problem. It made a problem worse. And as the cars made their way into downtown Boston, down Boylston Street, turned onto Tremont Street, it just got more crowded, and more crowded, and more crowded. Streetcars were pouring into downtown Boston.

Asha Weinstein Agrawal, Historian: Electrification made it easier to continue to expand the streetcar system farther and farther out, but there were a lot of safety concerns. These electric streetcars are more dangerous than the older horse-drawn ones and more pedestrians are getting killed by streetcars.

Narrator: Despite the chaos on the streets, Henry Whitney’s bold subway idea had been languishing for the past four years. That changed on the evening of January 5, 1891.

Henry Whitney hosted a banquet for influential real estate developers at the exclusive Algonquin Club.

Also in attendance was Boston’s newest mayor, Nathan Matthews. In his inaugural address earlier that day, Matthews pledged to deal aggressively with the rapid transit needs of the city. “I believe…the city government… should grapple with this problem,” he said, “rather than leave the matter entirely to the interested action of private corporations.”

Asha Weinstein Agrawal, Historian: Mayor Matthews was genuinely trying to improve the efficiency of the way the city government worked. And he very much is an example of the good government reform movement arguing that we need to make government more in the public interest. It should not be the system of patronage, people trading favors.

Doug Most, Author, The Race Underground: Boston, New York and the Incredible Rivalry that Built America’s First Subway: Nathan Matthews looked at Henry Whitney and started to wonder, “Maybe he’s never gonna build a subway.” And that’s when I think Matthews started to get frustrated and really dig his heels in to try to take back the streets of Boston from Henry Whitney and say, “These are city streets, and I’m going to be the one to make the big decisions about what we do, and how we do it, and when we do it, not you.”

Narrator: In speeches, Whitney explained that it was simply too expensive for the West End to build a subway. “I have, personally, no desire for anything that I can make out of the…underground road, to undertake it,” he said, “It is…so full of dangers…I am free to say to you that I shrink from the task.”

Mark Gelfand, Historian: This is an era in which cities and states are prepared to make significant investments in infrastructure. Matthews recognizes that in some respects the very well-being and future of the city is at stake in terms of its transportation needs, and that it may go against his grain to embark upon such a project as this, which offers the possibility of, of tremendous waste and corruption, but, nonetheless, is so essential to the city’s future that it must be undertaken.

Narrator: By June, Mayor Matthews followed through with his promise to take back the streets and convinced lawmakers to form the Rapid Transit Commission. Its mission was simple: study the problem of congestion and offer a solution. After 50 public hearings and 10 months of study the Commission published a massive report. All options were on the table, including something many deemed unthinkable: a subway beneath the Boston Common.

Stephen Puleo, Writer: The Boston Common is considered almost a sacred place to Bostonians and has been since the city was essentially founded in 1630. And it has been used throughout Boston’s history as a community gathering spot. There was sort of a pledge made by city fathers at the time that the Boston Common area would be kept free of any roadways, free of any development, and would be open space. Its very name, “The Boston Common,” means it’s for the common wealth, for the common good. It is a place for all Bostonians to be able to gather.

Brian Cudahy, Writer: “You’re going to dig up the Boston Common to build some sort of a silly thing that we’ve never heard of before?” People were horrified. There was a lot of opposition to it.

Narrator: “Save the Common” became the battle cry of outraged citizens. Letters poured in from across the country. Americans demanded not a single shovel disturb the sacred soil of the Boston Common. Protests were so passionate that an exasperated Matthews brought in two former Park Commissioners to defend the urgent need of a subway.

The young mayor also fought off plans for an elevated train system downtown, like the one running in New York.

Clifton Hood, Historian: Elevated railways block the sun. And so you’ve got entire avenues that are perpetually in a kind of twilight. The other thing is elevated trains were filthy. They’re run with steam locomotives and they vent cinders, smoke, black soot, and that settles on the city.

Brian Cudahy, Writer: One of the little tricks, a PR trick you might say, is that someone superimposed photographs of a New York steam-powered elevated train running down Tremont Street. And when people saw that they said, “Well, that’s no good either.”

Narrator: When the elevated plan was voted down, Matthews saw his chance and intensified his advocacy for a subway. Armed with data from the Rapid Transit Commission report, he argued that a subway would cut transit time by two-thirds to one-half and that streetcars travelling underground would not be crippled by inclement weather.

Stephen Puleo, Writer: The Boston subway was not a foregone conclusion, not by a long shot. There was tremendous resistance first by the merchants in downtown Boston. There was a petition at one point where 12,000 businessmen in Boston opposed the subway. There was going to be streets torn up, sewer systems affected, water lines affected, wires, electrical lines affected. Secondly, folks felt like traveling underground was very close to the nether world, that you were getting closer to the devil, that you were taking this great risk in God’s eyes by traveling on a subway.

Narrator: The debate had dragged on for months and Matthews was fed up. He had done everything he could to reassure Bostonians. He explained that the subway would not cut through the Common, it would only encroach upon its edge; the $5 million project would provide desperately needed jobs; the air underground would be safe to breathe.

“The facts of the matter simply are,” Matthews proclaimed, “that the streets of Boston are no longer highways for public travel…they are simply yards for the storage of cars…The time has come for action.”

On July 24, 1894, Bostonians went to the polls to vote on the city’s transportation future.

By the narrowest of margins the subway plan was approved.

On the morning of March 28, 1895, light snow dusted the hats and overcoats of a dozen men standing in a quiet corner of the Boston Common. With little ceremony, a shovel was driven into the ground and the transformation of the nation’s public transportation system began.

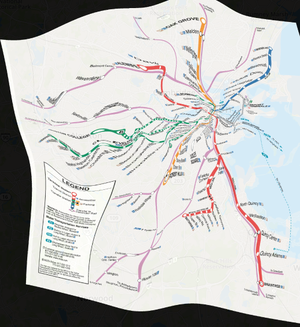

The 1.8-mile subway route would be built in two phases. The first phase was L-shaped, cutting through the heart of the city. Beginning at the southwest corner of the Boston Common, workers would dig east to the corner of Tremont and Boylston streets, before tunneling beneath Tremont to the base of the historic Park Street Church. The second phase would run from Park Street along Tremont to North Station.

Before excavation could begin every tree in the historic Boston Common was accounted for and 130 elms relocated.

Doug Most, Author, The Race Underground: Boston, New York and the Incredible Rivalry that Built America’s First Subway: Barely a month into the project a worker was bending down to pick up what he thought was a twig. They realized after studying it a little more closely that it was in fact not a twig and was a piece of a human skeleton. It was a bone.

Stephen Puleo, Writer: It turns out that this was the site of a Revolutionary graveyard, a burial ground and that the construction had disrupted that and everybody is taken aback by that. There’s real concern, “What are we gonna do about this? We need to handle this in a, in a reverential way.”

Narrator: In the coming months city workers identified 910 bodies and carefully reinterred them in a common grave.

Stephen Puleo, Writer: This gave ammunition to the opponents of the subway, about this religious issue that man was not meant to travel underground. And this was all symbolic of the fact that we shouldn’t be doing that, that God had a hand in this, in the discovery of this graveyard because He didn’t want us to do that.

Narrator: “They have sacrificed the Common,” one Boston newspaper bemoaned, “And now it seems that the dead are not to be allowed to rest quietly in their graves.”

Doug Most, Author, The Race Underground: Boston, New York and the Incredible Rivalry that Built America’s First Subway: They were being asked to put their faith in these engineers and just trust them that this would be safe. We’re going to build something underground, under the streets, and the street’s not going to collapse on us, and the subway’s going to be safe. And it was a big leap of faith for people to accept it, to embrace it.

Brian Cudahy, Writer: There had been underground aqueducts. There had been some underground tunnels. But this was a major construction novelty to build a steel and concrete structure beneath city streets. It was basically a work that was done by men with picks, and shovels, and wheelbarrows.

Narrator: Hundreds of Irish and Italian laborers worked for 15 cents an hour. They began to muscle their way deep into the Earth. First, 10 feet of the trench was excavated, the dirt tossed into carts and hauled away by horses.

As the trench deepened, workers installed 8-inch thick wooden braces against the walls to prevent collapse. Large derricks hoisted up dirt-filled skips and dumped the soil onto small steam trains that carried it away.

Steel I-beams were erected as sidewalls and laid across the top, serving as the roof of the tunnel. Above ground, masons finished the roof by laying brick arches atop the beams prior to being covered again with soil. A concrete foundation was poured, and then covered with crushed stone on which the steel tracks and wooden ties would be laid.

But not everyone was pleased with the work.

Stephen Puleo, Writer: During construction of the subway there is tremendous chaos in Boston. There are still above ground trolleys that are moving. There are merchants whose, the front of their stores are blocked by construction and by workers. So there is this enormous disruption, as you would imagine with any public works project, but think of one in a core city where you’re now attempting to go underground for the first time ever.

Rosalind Williams, Historian: That kind of heavy digging was not typically seen in the cities. I think it had to have been something of a shock to see this degree of excavation and also just to look down into these holes and wonder what’s going on down there.

Narrator: On the morning of March 4, 1897 Police Officer Michael Whalen detected the smell of gas at the intersection of Tremont and Boylston streets. It had been lingering for months as workers rerouted the gas lines beneath the streets. This day, however, it was stronger than usual.

As Whalen stood in front of the Hotel Pelham, three crowded streetcars rounded the corner. Trolley 461 caught Whalen’s attention and he looked down as its wheels screeched over the rails, causing sparks to fly in the air. On board the trolley, passengers gagged from the smell of gas.

The massive explosion ripped through the intersection. The shattered windows of the Hotel Pelham showered Officer Whalen in glass.

Doug Most, Author, The Race Underground: Boston, New York and the Incredible Rivalry that Built America’s First Subway: It sent both of these cars, which were filled with probably close to 100 passengers in all, straight up into the air in a huge ball of fire. It was a massive explosion and those cars came crashing down to the earth in a ball of flames.

Narrator: “A number of persons dashed up to an electric car,” one passenger recounted, “And to their horror found that the conductor was burning alive.”

In all, ten people were killed from the blast, and more than fifty gravely injured.

The media’s coverage of the explosion turned into a public relations nightmare for city officials. They now had to scramble to convince the public that riding underground on the subway’s electric trolleys was indeed safe.

Doug Most, Author, The Race Underground: Boston, New York and the Incredible Rivalry that Built America’s First Subway: Was the tunnel damaged? Did it crack? Was it destroyed? Nobody knew for sure right after the explosion. People were reminded of the fact that, “We’re going to be riding on a train in a dark tunnel surrounded by all of these gas lines.”

Stephen Puleo, Writer: The city and the state go to great lengths to explain that it was an accident, that a worker had mistakenly ruptured a gas pipe, which is what caused it, that is was not a natural gas issue. The subway was completely safe.

Narrator: Work on the subway proceeded apace, but nobody knew for certain if the city’s PR campaign registered with a public already skittish about traveling underground.

Doug Most, Author, The Race Underground: Boston, New York and the Incredible Rivalry that Built America’s First Subway: September 1st, 1897 it was a beautiful morning. It was bright and clear. And in a New England-like fashion, Boston was not prepared to do a huge celebration to announce the opening of its subway. There were no speeches planned. There were no big marquees, or giant signs, or anything like that. It was really just another day in Boston.

Narrator: The first streetcar, driven by the veteran West End motorman Jimmy Reed, left the Allston train shed at 6:00 AM. At each stop more and more people crowded onto car number 1752 until it was over capacity. Passengers excitedly waved American flags as they rode the first subway car in their country’s history.

Doug Most, Author, The Race Underground: Boston, New York and the Incredible Rivalry that Built America’s First Subway: It pulled up right to the crest of Arlington Street where it was going to go underground and into the tunnel. The first subway car just clanged its gong and just went down the ramp and everybody who was on the subway car stood up, glimpsed ahead to see what they could see and in fact someone on the back of the car yelled, “Down in front!”

Narrator: “The passengers…had packed themselves in like sardines,” noted the Boston Globe, “And…yelling like…wild animals, dipped down the incline for the underground run.”

Brian Cudahy, Writer: The headline in many papers was, “People Leave the Face of the Earth.” And they left the face of the earth and they went under it. People would previously leave the face of the earth in a condition where they wouldn’t return to the face of the earth. They’d be buried. Now people were traveling beneath the ground and emerging later.

Doug Most, Author, The Race Underground: Boston, New York and the Incredible Rivalry that Built America’s First Subway: People were just struck by how dry it was, and how clean the air smelled, and how it looked. It just looked beautiful, and sparkling, and white. There had been a lot of reasons to still be skeptical, and cynical, and fearful. All the things that people had been afraid of those fears washed away in that moment.

Rosalind Williams, Historian: They went to a lot of trouble to light these areas. That’s bringing the sublime into the underworld. That’s making you feel, “I’m safe. Nothing’s gonna harm me.” Those environments are hard to create, but they’re very effective when they’re done that way.

Narrator: Despite lingering fears and doubts, curiosity and excitement prevailed. City officials were shocked at the day’s final numbers: 250,000 people rode the underground rails of the subway on Boston’s first day.

Stephen Puleo, Writer: It was like a light switch went off once the subways began running. All of those aboveground trolleys in the downtown area are gone. It accomplishes exactly what it’s supposed to do. It alleviates congestion in the City of Boston and it creates a transportation grid and framework for the city for years and years to come.

Narrator: In its first year of operation fifty million passengers rode the Boston subway and the once frightening idea of riding a train underground became a part of daily life in cities across America. Within ten years of Boston’s unceremonious opening day, New York and Philadelphia opened their own subways with more American cities soon to follow.

Mark Gelfand, Historian: The decision to build a subway is remarkable in demonstrating how Americans were willing to try something new and place their bets on the future. That they understood that technology was reshaping their world and electricity, the tremendous potential of it, is going to be unleashed here in the subway system.

Narrator: Frank Sprague’s electrification of Richmond triggered a boon for the young engineer as he acquired over half of the 200 electric railway contracts in the country. His company, however, lacked the capital to compete with larger electrical manufacturers that were quickly expanding.

One year after Sprague’s demonstration in Richmond set the standard for electric railway systems across America, he was bought out by Edison General Electric Company. Shortly thereafter, Sprague’s name was removed from all the equipment he had developed and replaced with the Edison name.

Doug Most, Author, The Race Underground: Boston, New York and the Incredible Rivalry that Built America’s First Subway: Frank Julian Sprague lived in the shadow of one of the great inventors of all time, which is Thomas Edison. And I think because of that he never quite got the due and recognition that he really deserved. But Frank Sprague played as important a role in the development and growth of cities as any person in our history. His motor is one of the most important contributions, right there alongside Henry Ford’s vehicle and the Wright brothers’ plane, as one of the most important engineering achievements of our time.