Narrator: On October 17, 1971, the underdog Pittsburgh Pirates defeated the Baltimore Orioles in game seven to win the World Series. Many players had contributed to the victory, but everyone agreed who was most responsible — their veteran right fielder from Puerto Rico, Number 21, Roberto Clemente.

Narrator: But it wasn’t just his play on the field that day that his admirers would remember. It was what he did afterwards.

[Clemente interview in Spanish]

Juan Gonzales, writer: The Latinos who were listening to that were watching the English-language TV to have someone suddenly speak to you in Spanish, reinforced a pride in your own language and culture, and in who Roberto was.

Les Banos, friend: I cried when he did this, because this was him. He loved his family, he loved his country, he loved the United States but his love was for Puerto Rico.

Narrator: He was baseball’s first Latino superstar, before America’s pastime became truly international.

Robert Ruck, historian: Clemente is the first athlete to transcend both race and nation and culture. He’s also not defined by commercialism. It’s about pride, it’s about doing what he believes is right. It’s about loyalty.

Narrator: He played with unparalleled grace during turbulent times, with passion and pride that were often misunderstood.

George Will, writer: He was a puzzle I’m sure, to a lot of the sporting press, and they were, mysterious and somewhat adversarial in his view.

Samuel O. Regalado, historian: Clemente was a complicated individual, because he stepped into some very complicated times.

Narrator: He was larger than the game he loved, until his sudden, tragic death made him larger still.

Slate: Roberto Clemente

Narrator: “I grew up with people that really had to struggle to live,” Roberto Clemente recalled. “My mother never went to a show. She didn’t know how to dance.”

Like many others in rural Puerto Rico, life for Clemente’s family revolved around sugar cane. His father, Melchor, worked as a foreman in the fields near the small town of Carolina. His mother, Dona Luisa, often rose at one a.m. to make lunches for the workers. Roberto, the youngest of seven children, started working when he was just eight years old. Life in Carolina was hard, with more than its share of tragedy, but he remembered it fondly. “We used to get together at night and make jokes and eat whatever we had to eat,” he said later. “It was something wonderful to me.”

Shy, pensive, intelligent, Roberto was devoted to the island’s favorite sport.

David Maraniss, biographer: Baseball was it for Clemente from an early age. People in his neighborhood in San Anton who said they always saw him throwing something against the wall. It could be a sock or a bottle cap or something but he always had that motion of throwing.

Baseball captured Roberto as it did thousands and thousands of young boys in Puerto Rico in that era because it was what was available. Puerto Rico was not a soccer island. It was baseball.

Juan Gonzales, writer: In Puerto Rico, people argue and fight. The fanaticism toward baseball’s much greater [laughs] than it is here in the United States.

Narrator: As a teenager in the late 1940s, Clemente would catch the bus into San Juan to watch the Puerto Rican winter leagues, dreaming of his own baseball future.

Already a talented player himself, he watched some of the game’s best, including black players from America’s Negro Leagues, attracted by the island’s open racial climate.

Sports Announcer (archival): It’s a high pop-up. Back for first base that’s second baseman, Taylor, scooting over near the line to make the catch for the out…

David Maraniss, biographer: It was so different in Puerto Rico from in the United States in that period. If you were black Puerto Rican or black American, you could eat wherever you wanted to, you could sleep wherever you wanted to, you could date whoever you wanted to, there wasn’t this constant reminder of the color of your skin.

Narrator: Following his favorite team, the San Juan Senadores, Clemente saw top ballplayers, black and white, play with the Caribbean League’s trademark swashbuckling style. For fifteen cents, Clemente could watch the outfield play of his idol, Negro league veteran Monte Irvin.

Samuel O. Regalado, historian: For Roberto Clemente, the black ball players in many respects represented a very important time in his youth. They were the standard bearers for Roberto Clemente. They were the models.

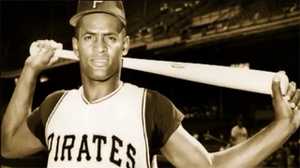

Narrator: At eighteen, Clemente got his first break, playing for the Santurce Cangrejeros for 40 dollars a week. Soon the island’s top baseball men were talking about the young outfielder with the quick bat and the rocket arm. One called him “the best free agent athlete I’ve ever seen.”

In 1954, Melchor Clemente signed a contract on behalf of his son with the Brooklyn Dodger organization, for the unimaginable sum of $5000, plus a $10,000 signing bonus. His stay with the Dodgers would be short-lived — he would soon be drafted away by the Pittsburgh Pirates — but Roberto Clemente was living the dream of every Puerto Rican kid boy who’d ever swung a bat. He was on his way north, to play baseball en las grandes ligas.

Announcer (archival): At Fort Myers, training begins for the Pittsburgh Pirates …

Narrator: For twenty-year-old Roberto Clemente, the annual ritual of spring training in Florida was both familiar and strange. He had played baseball in a warm sunny climate before. But he had never encountered Jim Crow.

Samuel O. Regalado, historian: They’re training in the south, and it’s in the south that Roberto Clemente like other Latin American blacks are introduced to the overt racism they had heard about back in their homeland but now actually see in front of them, and it’s really a concept that is very difficult for them to grasp.

David Maraniss, biographer: The whole team stayed at the Bradford Hotel downtown except for Clemente and three other black and Latino players who had to find their own lodging on the other side of the tracks, literally. In every aspect of his life there he felt segregation strongly for really the first time in his life.

Juan Gonzales, writer: He was coming here as an American, playing baseball in his country, but he was being treated as a black American, as a foreigner, the way he was being identified that just didn’t jibe with his reality.

Samuel O. Regalado, historian: You had this combination of young ballplayer, anxious to succeed, has to a certain extent delusions of grandeur, and then there’s the reality of his position as a person and in the south during the period of the 1950s, it didn’t matter whether or not you’re a professional baseball player, you’re just black.

Narrator: With the start of the regular season, the team came north to Pittsburgh, a tough, smoke-belching steel town, where Clemente took a room in a middle-class African-American neighborhood.

Pittsburgh fans loved their Bucs, as they called the team; but they didn’t quite know what to make of their lone Latino player; and Clemente did not quite know what to make of Pittsburgh.

Robert Ruck, historian: You were black or you were white in Pittsburgh. You weren’t Latin. You weren’t Puerto Rican. On the other hand I suspect that both black and white Pittsburghers had a hard time understanding Clemente. They had little experience with people from Latin America, with Latin American culture, with that sense of Latin pride. The black community saw him and physically he was black to them, but not culturally.

Orlando Cepeda, San Francisco Giants: He told me that, that it was very lonely for him because of communication — he couldn’t communicate, and that’s why — we have two strikes: being black, and being Latin.

Narrator: Clemente spent little free time with his fellow Pirates, some of whom found him guarded and aloof. Whatever the reason, the result was obvious: besides baseball, #21 and his teammates had little in common.

Samuel O. Regalado, historian: Clemente after baseball games has no one really to pal around with in terms of his teammates. He often wanders around by himself and Clemente, in fact, signed autographs till the last person had his baseball signed in large part because Clemente had really nothing else better to do that day after games.

Narrator: In the days before publicists and security guards, players and fans could sometimes have a human encounter. One day, a seventeen-year-old fan from rural Pennsylvania saw Clemente after a Phillies game.

Carol Brezovec Bass: I decided to approach him and I said, “May I please have your autograph?” — and I had just begun to learn some Spanish and so I said, “O, gracias, ah, Señor Clemente” and he smiled and he looked up and he started to rattle and go off into Spanish. And he just went on and on, and I was just like, um, you know, so nervous inside and I thought, “Oh my gosh, you know, how do I, you know, what do I do to tell him, you know, I don’t understand what he, what he had to say.”

“Mr. Clemente, I’m so sorry.” I said, um “I’m just beginning to learn Spanish, I only know a few words, Well he, you know, started to laugh, he said, you know, “You’re never going to get a lot of autographs being so far back.”

David Maraniss, biographer: An athlete’s life is mostly being uprooted. And a lot of athletes deal with that by finding superficial outlets. Clemente mostly dealt with it by trying to find reminders of home and family wherever he was. Carol was one part of that in an unlikely white girl from Philadelphia becomes part of the Clemente family.

Narrator: Over the years, Clemente would host Carol and her parents when they visited him in Puerto Rico. But friendships with individual fans were one thing; relations with Pittsburgh’s hard-bitten press were quite another.

Theirs was an awkward dance of mutual incomprehension and often hostility.

Roy McHugh, sportswriter: If Clemente wasn’t approached in the right way, he would flare up. His feelings seemed to be right on the surface. And after the wrong question or the wrong word would set him off. I can’t say that I enjoyed talking with him.

Al Oliver, teammate: What cracked me up about Roberto was in a lot of his interviews, they would come and interview him, he would start talking about life. And the writers just weren’t ready for that.

Narrator: Baseball players were supposed to be upbeat, and uncomplicated; not Clemente. The Pirate outfielder was often moody, haunted by chronic insomnia, a serious man ill-at-ease in a boisterous locker room.

An accent didn’t help.

[Clemente speaking heavily-accented Spanish]

Narrator: For much of the Pittsburgh press, it seemed a Latino player’s background was something to be mocked, or ignored.

Juan Gonzales, writer: There was an attempt to really sort of deny the Latino heritage of these ballplayers. I was, uh, just a kid then, but I remember he was always called Bobby Clemente. They Americanized the names and always the sports writers and the ball players ridiculed their attempts to speak English.

Al Oliver, teammate: Bottom line was there wasn’t a lot of knowledge of Puerto Rican players. There wasn’t a lot of knowledge of even black players at that particular time. And it had a lot to do with not being around. If you’re not around a certain group of people, then you form opinions.

Narrator: Clemente repeatedly broke an unwritten rule for professional athletes: never say what’s really on your mind. And another: never complain about injuries, aches, or pains.

Roberto Clemente (archival): Well, last year I wasn’t feeling good last year and I hit .312 and I hope with my rest and my stomach will stop hurting me I feel, I think I can have a better year. I hope so anyhow. I was, uh, under-weight, under-weight last year. I was having a little trouble with my stomach.

Narrator: His stomach, his back, his legs, his neck — everything seemed to plague him at some point. Before long, Clemente acquired a reputation as an oversensitive hypochondriac.

Roy McHugh, sportswriter: One day after a game, he was sitting in front of his locker with his uniform off and Joe Brown the general manager told him to get into the shower and get dressed. He said, “You’ll catch a cold,” he said “I don’t want you to be sick.” Clemente said, “I feel better when I’m sick.” I don’t know what he meant by that but he knew what he meant.

George Will, writer: We acquired a national stoicism from the thirties and our troubles in the Depression, from the forties from the war. Stoicism was identified with manliness, and it was thought somehow less than manly to complain about ailments, even though real.

Robert Ruck, historian: White ballplayers and black ballplayers uh, were relatively taciturn, they chewed tobacco. Not too many of them had a great sense of style or flair. Certainly if they asked these players questions about how they were feeling and the player actually talked about their feelings, that was not something they were accustomed to.

Pirates player (archival): Frank, there’s a lot of reasons for it. I believe the biggest one being confidence, the main thing and uh, swinging the bat.

Narrator: There was a source for some of Clemente’s pain, but he seldom spoke of it. Back in 1954 he had been in a serious car accident that damaged his spine and neck. The injuries would plague him for the rest of his life.

Stung by what he saw as unfair criticism, Clemente lashed out at his detractors. “Hypochondriacs don’t produce,” he growled. “I produce!”

George Will, writer: Clemente played hard all the time, he played all the time, but he talked all the time about how hard it was to do what he did. And I think it grated on some people who thought that the ideal ballplayer should be like Gary Cooper — tall, silent, stoical.

Narrator: In his first five seasons with the Pirates, Clemente hadn’t exactly lit up Forbes Field with his hitting. He’d batted over .300 only once, with seven or less homers. His play in right field was something else: he’d won over a growing number of local fans with his powerful arm and remarkable range. Still, he was on a lackluster team and the national press barely noticed.

Until, that is, 1960.

Samuel O. Regalado, historian: In 1960, the Pittsburgh Pirates were no longer the laughing stock of baseball. The Pittsburgh Pirates are champions of the national league.

Narrator: That year, Clemente led the team in runs batted in, was second in home runs and game-winning hits, and led the league in outfield assists.

Samuel O. Regalado, historian: By 1960 he is an all-star player in the national league. He is becoming a real threat to opponents. He might not be recognized by the national media, but on the baseball diamond, clearly his opponents recognize Roberto Clemente’s rising star.

Narrator: For the first time in 33 years, the Pirates found themselves playing in the World Series. Unluckily, they had to face the New York Yankees, winner of five titles in the past decade, and a team packed with superstars such as Mickey Mantle, Yogi Berra, and Whitey Ford.

Robert Ruck, historian: The 1960 series was David and Goliath. The Yankees were the franchise of professional sport, winning more titles than any team in any sport.

David Maraniss, biographer: The Pittsburgh Pirates came into the World Series as massive underdogs. They have a very good team but no one had really heard of the Pirates players.

Narrator: Helped by some timely hitting from Clemente, and his outfield play, the Pirates managed to win three of the first six games, despite being outscored by the powerful Yankees, 46 to 17. The seventh and deciding game would be played in Pittsburgh, where only the most diehard Bucs fans gave the home team much of a chance.

In the bottom of the ninth inning, David and Goliath were tied, 9-9. As Pittsburgh held its collective breath, Pirate second baseman Bill Mazeroski came to the plate. When Mazeroski reached home, Clemente was there, celebrating one of the great upsets in baseball history, proud of his own big contribution to the team’s success. Once off the field, he expected to make a quick exit and catch a plane home to Puerto Rico.

But he hadn’t counted on the scene outside the clubhouse. “There’s Clemente!” someone shouted and the crowd surged forward. It took him an hour to make his way through. After years of feeling himself an outsider, he had won them over. The fans of Pittsburgh, he said, had made it all worthwhile.

Finally back in San Juan, at the airport, Clemente received a greeting befitting a returning hero. Proud Puerto Ricans had followed the series closely on the radio, and in the papers — a sign in the crowd said what every one felt about their triumphant native son. He had barely touched ground when the crowd scooped him up and carried him away.

Juan Gonzales, writer: He was the hero of the island. He was like a God. The pride that Puerto Ricans felt over what he had managed to accomplish in baseball was incredible.

Narrator: The celebration went on for weeks. During the day, dressed in his major league uniform, he led clinics for groups of worshipful Puerto Rican kids. Most nights, he attended banquets held in his honor.

But Clemente had a different kind of honor in mind — the National League’s Most Valuable Player Award for the 1960 season. On November 17, the results were finally announced. In the vote of the nation’s baseball writers for the league’s top player, Clemente finished eighth. He took it hard.

Les Banos, friend: He felt that he did the best performance in his life in the 1960 World Series and personally, he felt this, he should deserve the most valuable player for this, but he didn’t get it. And he felt you know a certain amount of prejudice was involved at the time.

George Will, writer: He was very sensitive to slights and to the sense that he was not noticed. Clemente’s resentment arose from, first, his pride. Second, from the injustice of the vote — you can’t say absolutely that Clemente should have been the MVP, but there weren’t seven more valuable players in the National League than Clemente that year.

David Maraniss, biographer: I’ve heard that he never wore his World Series ring after that because he was so upset. Whether that’s apocryphal or not, it represents accurately the way he felt. He felt that he had been done in by racism. It was sort of a reminder that life in America was different from his life in Puerto Rico, that the way he was regarded was different, and worse, and that he would not allow that to happen again.

Narrator: Roberto Clemente arrived for spring training in 1961 with a new contract worth $35,000, and something to prove. Fueled by his anger at being overlooked, the 27-year-old Pirate outfielder lifted his play to a new level. That year he would hit a league-leading .351, while playing stellar defense. Even as the Pirates returned to their old losing ways, Clemente was emerging as one of the greatest right fielders in the game of baseball.

Juan Gonzales, writer: Over 50 years I’ve watched many, many baseball games in my lifetime, I can never remember anyone who threw a ball, uh, better than Roberto Clemente when there was a base runner heading to third or a base runner trying to score at home. It was a rifle, it was an incredible arm that he had and incredibly accurate. And so there were some ways that he was so superior to all the other ballplayers that all of the issues of race and, and nationality and language all fell by the wayside once the game started.

George Will, writer: He would gesture and move his shoulders and his neck as though we were trying to work the kinks out. Then, he would settle himself in the batter’s box, and all hell would break loose.

Robert Ruck, historian: Clemente played with abandon. He was like a horse galloping around the bases, arms flailing.

Steve Blass, teammate: The way he handled his body was incredible. I mean just incredible. It looks like he was galloping. Looked like he was all arms, but got there quickly. His body was a baseball machine.

George Will, writer: So in every facet of the game — hitting, catching, hitting with power, throwing the ball — the classic five-tool player, that was Roberto Clemente.

Narrator: Across the U.S., the Pirates’ talented right fielder was now being cheered by a growing number of Latino fans. Through the 1960s, a surge in immigration from Latin America and the Caribbean brought new faces to US cities — and to baseball dugouts as well.

When Clemente first entered the major leagues in 1955, there had been only a handful of Latino players; now, nearly a decade later, there were dozens. But not everyone in baseball welcomed the trend.

George Will, writer: Alvin Dark, the manager of the San Francisco Giants, forbad the speaking of Spanish in the clubhouse — he thought that Hispanic players were somehow an alien presence and a threat to cohesion. I don’t know what the thinking was.

Narrator: Number 21 realized that to fans and fellow players alike, he had become something more than a right fielder. He had become a role model.

Les Banos, friend: He was very careful always, his appearance. Because he felt the first impression very important, especially from him. Because he felt he not representing Roberto Clemente alone, he always told me, I’m representing the people of Puerto Rico.

George Will, writer: He represented impatience, he was a cauldron of energy, representing the upward mobility, of people who had hitherto been excluded.

Narrator: Each October, after the baseball season ended, Roberto would return to Puerto Rico. Driving the streets of San Juan in his white Cadillac, he attracted attention worthy of a movie star. He was still in his twenties, handsome, famous and single.

David Maraniss, biographer: He was magnetic. There were always women writing him love letters, trying to be near him and it wasn’t that he was just walking around, prowling as a hunk. He was a very soft guy who wanted to hear other people’s stories and so that added to his magnetism.

Narrator: After a decade on the road, Clemente was eager to settle down. Vera Zabalo was striking, a twenty-two year-old college graduate who worked in a bank. And she was from Carolina, Clemente’s beloved childhood home, where her father had worked in the local sugar cane fields.

David Maraniss, biographer: She didn’t even know that Roberto Clemente was a ball player, he started calling her at work, asking her for dates, and eventually Clemente got up the nerve to sort of deal with the father.

Vera Clemente, wife [in Spanish, subtitled]: My father said to him, “I don’t know why you are here. We are a humble family and you are a famous man. You must know many pretty women, some even with money. We don’t have any money, so I don’t know why you are here. Roberto said, “Other women don’t interest me. The one that I love is here.”

Narrator: November 14, 1964, the couple married and settled down in Carolina. The next year, Vera gave birth to a son. Two more boys would follow. Vera soon discovered that her husband had some eccentricities.

David Maraniss, biographer: Clemente was kind of new age before there was new age. He was an incredible masseuse, he was constantly taking different proteins and odd concoctions of shakes to try to stay healthy. He believed in sort of mystical connections between life and death and people who were no longer around.

Narrator: His connection to the dead centered on a childhood tragedy, the loss of his sister, Anairis, burned to death in a kitchen accident when Roberto was just an infant. For the rest of his life, he would be haunted by fire, and by thoughts of his own mortality.

David Maraniss, biographer: He had talked for the rest of his life about feeling his sister at his side. He had a certain melancholy to him. You see it in his eyes.

Vera Clemente, wife [in Spanish, subtitled]: He had special “timing.” For instance, he was in a hurry to get married. Because he always thought he would die young.

Narrator: In the mid-1960s, Clemente found himself engaged by events beyond the ballpark, as America entered a time of unprecedented change. As Clemente watched and read about the protesters pouring into the nation’s streets, he identified closely with the widening movement for civil rights.

David Maraniss, biographer: Clemente was interested in more than sports. He was very political. And one of the people he admired most in the world was Martin Luther King. The one time we know that Dr. King went down to Puerto Rico, Clemente uh sought him out and spent most of a day with him, took him to his farm.

Robert Ruck, historian: Because he’s in the black community and because he’s traveling around it’s clear at that time that this is a guy that’s interested in what’s going on around him and has opinions about that. He’s not only an observer, he’s somebody who’s passionately connected to what’s going on. He’s talking about those things. He’s arguing about those things.

David Maraniss, biographer: It goes back to the way they were treated in spring training when they were on those buses going from one town to another and the white guys would go into a restaurant and bring back sandwiches to the, Clemente and a few blacks and Latinos. That was not going to fly with Clemente.

Roberto Clemente (archival): Now we are in Florida, not too far from Puerto Rico and you see the white players go to the restaurant and they say, “Fellas, do you want anything to eat?” Now we are sitting in the back of the … we’re sitting in the bus, we weren’t sitting in the back of the bus but we were sitting inside the bus, and I remember I said, “Look if you’re going to accept anything from anybody from that restaurant then you and me are gonna have it. We will have a fight because I think it’s not fair if this is the way it’s going to be, if this is the way we’re going to suffer. And so now, I don’t want you — none of the fellas to eat anything.”

Narrator: Celebrity did little to dull his sensitivity to injustice; if anything, it only sharpened it. Once, out shopping with Vera in a New York department store, the couple was ignored until someone recognized the famous ballplayer. When the salespeople suddenly lavished them with attention, Clemente would have none of it.

Vera Clemente, Wife [in Spanish, subtitled]: Roberto told the clerk, “I asked you to show us the best furniture. Why did you take so long? We’re not going to buy anything now.”

Narrator: By the end of the decade, increased Latino immigration and a galvanized civil rights movement was transforming the country. Baseball was changing too, with the Pirates leading the way. In 1971, Clemente found himself leader of a team unlike any in baseball history.

Steve Blass, teammate: It’s almost Latin, black and white. ... It sounds so trite and so contrived, but we had a bunch of guys who could play.

Manny Sanguillén, teammate [Spanish, subtitled]:We were like a family back then. We weren’t thinking about color. We just wanted to win.

David Maraniss, biographer: It was a time of change and transformation that scared a lot of people and one of the manifestations of that was that the Pirates as they became more black and Latino became less popular in the city.

Robert Ruck, historian: Roberto is the guy they look up to, white, black and Latin. They look up to him because he delivers on the field, but he’s the guy that holds them together off the field. And he’s much more of a leader, much more of a clubhouse presence by 1971, which in many ways is his coming out party to the world.

Narrator: In 1971, Pittsburgh managed to reach the World Series once again. At 37, the oldest player in the Series, Clemente had battled injuries all season. But his intensity hadn’t diminished, nor his competitive drive.

Les Banos, friend: He pulled me aside, he said, I guarantee you, we going to win. And I told him, Roberto, you cannot say anything like it because if it don’t turn out to be, you’ll be a laughing stock, everybody make a joke out of it.

Matino Clemente, brother [in Spanish, subtitled]: He liked to play under pressure. Other players don’t. Because if you fail, they’ll eat you alive.

David Maraniss, biographer: He came up to Jose Pagan, one of his teammates, and said you guys just get on my back and I’ll carry you.

Narrator: The Baltimore Orioles had four 20 game winners on their pitching staff, and were hands down favorites in the series. That didn’t faze #21.

David Maraniss, biographer: There was one moment that overwhelmed everything else and it wasn’t a throw or a great hit. It was a dribbler that Clemente hit back to the Baltimore pitcher Mike Cuellar.

Robert Ruck, historian: That caused the pitcher to throw wildly. He wasn’t just going to assume that the pitcher was going to throw him out. And it was his hustle that did it.

David Maraniss, biographer: Everybody I’ve talked to on both teams said that they could just feel Clemente’s overwhelming will to win dominating that series.

Narrator: After the two teams traded wins, forcing a seventh game, Clemente reassured his nervous teammates. In the fourth inning, he blasted a towering home run, breaking a scoreless tie; five innings later, the Pirates were World Champions.

David Maraniss, biographer: Clemente was brilliant in that World Series. He batted .414, he got a hit in every game, he was terrific in right field, but it was more than any of that.

George Will, writer: His performance was a jewel — one of the greatest performances, five or six or seven, in World Series history.

Narrator: In the jubilant Pirate locker room, Clemente took the opportunity to speak directly to those who mattered most to him.

[Clemente interview in Spanish]

Juan Gonzales, writer: Roberto was breaking the mold in saying, “Yes, I Will talk to you. But first let me talk to my family and, and my community.” I think that was enormously important certainly for those Latino fans here in the United States as well as those in Puerto Rico and Latin America who were also listening to that.

Osvaldo Gil, friend [in Spanish, subtitled]: It is the greatest day of his life, what is his first thought? Family and country. I think that’s why he spoke Spanish.

Steve Blass, teammate: It’s still chaotic and everything, we get on the airplane, and before we take off, I’m sitting by the window, Karen is in the middle seat, Roberto Clemente comes up the aisle, and looks at me, I’m sitting there, he says, “Come here Blass, let me embrace you.” And I walked up and he gave me this big hug, and I get goose bumps now thinking about it. Here’s Roberto Clemente getting up out of his seat coming up and wanting to give me a hug and it just, it validated everything that I ever thought that could happen to me in the game of baseball.

Narrator: Over a remarkable career, Clemente had converted even the skeptics. Four batting titles. National League MVP. The next season, 1972, would see him reach one of baseball’s most prestigious milestones, 3000 career hits. But the game’s best right fielder had other things on his mind.

Robert Ruck, historian: There’s something going on, with Clemente in the later years where he’s making a transition from ballplayer to a statesman, you know from somebody who is putting up Hall of Fame numbers on the field, but to somebody who you can just see what he’s becoming off the field. He’s spending a lot of his time thinking about things, planning things, beginning projects which he hoped to accomplish once he left the ball field for good.

Narrator: That winter, Clemente found corporate sponsors for baseball clinics across Puerto Rico, and worked on plans for his passion, an ambitious sports city for underprivileged kids. He traveled more widely throughout Latin America, and even coached an amateur team in Nicaragua.

Osvaldo Gil, friend [in Spanish, subtitled]: What he saw on the streets of Nicaragua — had a big impact on Roberto. It moved him.

Robert Ruck, historian: I think that Nicaragua in 1972 did remind Roberto of what Puerto Rico was like when he was a boy in the thirties and the forties. He approached kids and kids approached him and he talked to them and he went to their homes and he found out that about their lives and he identified with them.

Narrator: On December 23, 1972, the Clementes awoke in Puerto Rico to the news of a massive earthquake in Nicaragua. Roberto quickly located a ham radio operator who could provide details of the damage, and asked what help people on the ground could use. The reply was blunt, and for Clemente, heart-wrenching: Food, clothing, medical supplies. Everything. He threw himself into the relief effort, body and soul.

David Maraniss, biographer: It became his passion for the next week or so he was … that’s all he was doing, day and night, was trying to round up aid for the people of Managua.

Narrator: When he heard the news of corruption and looting, of relief supplies stolen, Clemente decided to intervene — personally. He would accompany a planeload of emergency supplies to Nicaragua.

Robert Ruck, historian: The people on the ground in Managua are calling Roberto. Roberto, you have to come. If you come here, it’ll get where it needs to go.

Narrator: Clemente wasted no time. At San Juan’s International Airport, he chartered the first plane and pilot he could find. After some frantic hours of repairs, the DC-7 was finally cleared for take off.

It was a few minutes after 9pm, December 31, 1972.

Vera Clemente, wife [in Spanish, subtitled]: We said goodbye on the tarmac, and he climbed the stairs to the plane. He gave me a very sad look. I read many things in that look. “I would like to bring you, but I can’t. I should stay, but I can’t.”

David Maraniss, biographer: The plane was sort of tipping wrong. And the front wheel was a little … almost off the ground and the back wheel was smashed, and said something, something’s wrong here. But Clemente was so determined to get to Nicaragua to do what he thought he had to do that he wasn’t really paying attention to any of that stuff. It barely got off the ground, just over the trees, over the ocean about a mile and it disappeared.

Narrator: Just as Clemente’s plane departed, Carol Brezevec and her mother were just arriving on the island. Vera had gone to the terminal to meet her.

Carol Brezovec Bass: She was explaining to us, you know, what had happened, and how, ah, she had taken Roberto to the airport, and that, um, he was on his way to Nicaragua and that he would call as soon as he got there.

Narrator: But the phone call never came. Late that night, Clemente’s niece called Vera. She had heard a radio report that a plane had crashed into the ocean just after take off.

Carol Brezovec Bass: Things just became much more serious and much more quiet. By then, there should have been a phone call from Roberto, to say he was okay, you know, I’m here, I’ll be right back.

Narrator: The following day, helicopters and a rescue fleet surveyed the waters off San Juan, to no avail, as a disbelieving crowd gathered on the beach, praying for a miracle.

Carol Brezovec Bass: You know, the reality became more clear as we would see more and more medical supplies wash up and signs that in fact this was the cargo plane and this was the plane that, um, he was on.

Narrator: Pittsburgh teammates waited anxiously for news; one even joined in the rescue effort. But Roberto Clemente’s body would never be found.

Manny Sanguillén, teammate [in Spanish, subtitled]: The tide pulled everything away. They couldn’t see anything.

Slate: Headline: “Bucs’ Clemente Killed In Crash”

Al Oliver, teammate: It knocked me off my feet. You looked at Roberto as someone who was invincible. We knew that we had lost our leader.

Juan Gonzales, writer: It was two days after his death, and I come out of my apartment in the South Bronx and people are pouring out with cans of food, blankets and other supplies uh, to give to the victims of the earthquake in Nicaragua. Here were all of these Puerto Ricans, all of them impoverished themselves, and to some degree it seemed to me their way of, like, expressing not only their sense of loss over Clemente, but their sense of continuing what he was trying to do. And that truck filled up in, in half an hour.

George Will, writer: Great athletes compress life’s trajectory — a naturally rapid ascent, glamorous apogee, slow decline. Most great athletes live most of their life after their life, as it were. Didn’t you used to be a ballplayer. Clemente was great and gorgeous to watch, elegant, noble — right until this horribly abrupt end.

Osvaldo Gil, friend [in Spanish, subtitled]: My mother gave me the only explanation that made sense. “If he had died as a player, only the sports fans would have remembered him. But by dying while helping others, he would be remembered as a humanitarian.” And she was right.

Slate: Less than three months after his death, following an unprecedented vote, Roberto Clemente became the first Latino player elected to Baseball’s Hall of Fame.