Patrick Jagoda, Gaming Scholar: We played on vacation and it never ended well. I mean, it would always end in a fight. It was either somebody was cheating. These weren't the rules, right? There were always house rules that we were applying. So it was a very intense series of games growing up.

Mary Pilon, Writer: We always played Monopoly at Christmas Eve. That was our family tradition. Still is. As a kid, it wasn’t just exciting to win at a game but also seeing my brother get destroyed as the little sister was a very exciting feeling if I had to be honest about it.

Ashlyn Sparrow, Game Designer: It’s America’s game, right? It’s all of our game. It’s the game of our childhood.

Eric Zimmerman, Game Designer: But, there’s a dark side too, it’s not all, you know, rainbows and unicorns. It’s a cutthroat game, I only win when you lose.

Bryant Simon, Historian: In America, we’ve created a myth that capitalists like competition, but no capitalist wants competition. What all companies want is a monopoly.

Patrick Jagoda, Gaming Scholar: This story about Monopoly is filled with ironies. I mean this is one of the things that makes it so compelling. It’s not just the twists and turns, but the fact that it is a game about capitalism that was created to teach people about something completely different.

Kate Raworth, Economist: The dynamics written into the rules of this game were never intended to be the rules. It should come with a health warning like a packet of cigarettes. You are playing a twisted version of this game.

Tom Forsyth, Game Historian: It was supposed to be a critique of capitalism and it turned out to be a celebration of it.

Kate Raworth, Economist: And so this is a story that teaches us: compete, acquire, be ruthless and you will go on to conquer the world. It’s Monopoly through and through.

Verite of kids opening a box and playing Monopoly

Soren: Read the instructions–somebody pass me…pass me the instructions.

Lula: Uh, what piece do you guys want to be?

Deacon: Okay…

Soren: I’ll be…car.

Ruby: I want to be the hat.

Soren: So Ruby, you’re the banker.

Milo: I want to be the banker.

Soren: Okay so…

Lula: How much money do we get out?

Soren: I think like 500.

Milo: Two of each, 500’s, everybody gets two 500’s.

Milo: And six 20’s.

Lula: This is a lot of money.

Ruby: I know. My goal in life is to win and beat you all.

Lula: Wow.

The Official Story

Mary Pilon, Writer: Once upon a time in the Great, Great Depression there's this man named Charles Darrow. He's unemployed as are millions of Americans. He has this big light bulb moment, this big Eureka moment, and out comes Monopoly. He’s told no one will buy this game. It’s a game about property and money at a time when Americans are so desperately lacking exactly those things. But undeterred, he ultimately ends up at Parker Brothers. They decide to sell the game, it becomes a massive best-seller, and it saves him and Parker Brothers from the brink of destruction. Everybody lives happily ever after (LAUGHS)

Mary Pilon, Writer: There's just one problem with that story . . . and it's that it’s not true.

Ralph – Anti-Monopoly Is Born

San Francisco, 1973

Mary Pilon, Writer: In the early 1970s, Ralph Anspach is an economics professor at San Francisco State University. Ralph is an impassioned anti-monopolist. He thinks that monopolies are at the root of all that is wrong in this country and create power imbalances. His ideas aren’t getting across and he’s frustrated, because at this point the OPEC oil cartels are dominating headlines.

Tristan Donovan, Writer: OPEC, the heir of oil monopoly, controls the oil supply. They’ve just hiked up prices, there are queues at the petrol pumps, the economy is in tatters. It’s a crisis, an absolute crisis in 1973.

Patrick Jagoda, Gaming Scholar: Ralph believed that monopolies were one of the major forces holding back the optimal version of American capitalism. And so what better way to teach people about those complex systems than having them play and experience a board game.

Steve (Off Camera): Ralph tell me about the board game that you invented, and how did it come about?

Ralph Anspach, New York City, 2005: It was a very hot day, chaos on the roads, took me about four hours rather than one hour to get home, and when I finally sat down at the dinner table I was X-rated cussing out the oil monopolists. And suddenly my eight year old son says dad you are a really poor loser. I said why William, why am I a poor loser. He said yesterday we played Monopoly, I won the game, now you’re such a poor loser you’re attacking my victory. I tried to explain to them ‘you shouldn’t take it personal’ and I started looking for a game that would show the Anti-Monopoly side. Unfortunately there was no such game. I began to think about that and that’s what happened, I invented Anti-Monopoly.

Mary Pilon, Writer: Anti-Monopoly becomes a hit in the Bay Area. It's sold at local stores. Patty Hearst reportedly plays a version of the game. And it becomes kind of this counter-cultural icon.

Ralph Anspach, New York City, 2005: The point of Anti-Monopoly was to retain all the fun of Monopoly, but at the same time, make it very clear that the monopolists are the bad guys when they play. Anti-Monopoly has a message. Monopolies are not a nice thing in capitalism, it's the dark underside of capitalism.

Tristan Donovan, Writer: Anti-Monopoly is there to basically turn the tables on the Parker Brothers game. Instead of trying to build a Monopoly, you try to break them up. There’ll be steel Monopolies to smash, oil monopolies to smash. So, you know it was about busting these giant corporations.

Mary Pilon, Writer: Anti-Monopoly takes off, it starts selling, all over the country. And it looks like it’s going to be a huge hit. And then one day, Ralph receives a letter. It was from attorneys who represent General Mills, which at that point owned Parker Brothers and they say you can not sell Anti-Monopoly. You are infringing upon our right to sell our game.

Ralph Anspach, New York City, 2005: The letter said, 'Take the game off the market immediately, destroy all games you have, and also, we want you to put an ad in newspapers saying that you’re sorry that you attacked us,’ and so on and so forth, and that’s how it began. It was enough to frighten anybody out of their wits, but I get mad about things like that when some big company attacks a little guy, for what I consider to be no-valid reason. So, I got ready to fight.

Mary Pilon, Writer: Ralph’s a very cause-driven guy, and I think some of that’s from his childhood.

Tristan Donovan, Writer: Ralph was born in the city of Danzig. He was Jewish. Somewhere around the age of 12, his family moved to New York to escape the coming Nazi threat.

Mary Pilon, Writer: He’s a scrappy kid in New York City, he doesn’t know the language. And then works his way through school, eventually to getting his doctorate.

Tristan Donovan, Writer: I think this gave him a kind of attitude of I need to stand up to bullies. You know, if someone was trying to push him into a corner, he’s gonna hit back.

Ralph Anspach, New York City, 2005: We’ve sold a half million Anti-Monopolies and not a single consumer has complained to us or to Parker Brothers.

Interviewer: Complained about confusion you mean?

Ralph Anspach, New York City, 2005: That’s right, not a single person claimed that they had bought the Anti-Monopoly and they thought it was a General Mills game or something like that.

Mary Pilon, Writer: Now, he lawyers up and he serves a counter punch. He actually sues Parker Brothers first. So that way he can claim jurisdiction in California. Part of Ralph's strategy is to prove that the Monopoly trademark is dubious. So Ralph is on a mission to piece together Monopoly’s early history, trying to find out what happened with the game before Parker Brothers started to sell it.

Tom Forsyth, Game Historian: And then one day, Ralph is working at home and his son, Mark, comes running into his office and says, ‘Dad! Dad! There’s this book I’ve been reading and it says that Monopoly was invented by a woman. This woman Lizzie Magie.’ Ralph is like, ‘Wait, who’s Lizzie Magie?’

Lizzie Magie/Early Board Games

Mary Pilon, Writer: Elizabeth Magie was born in 1866 in Macomb, Illinois. Her family was very political, her father was a very influential newspaper owner, he was one of the early founders of the Republican Party. He had traveled with Abraham Lincoln during the Stephen Douglas debates. She was exposed to a lot of big ideas. And at a time when women were not afforded many opportunities to be in the public space, she took every single one that she could. She was an actress, she was politically very active.

Ashlyn Sparrow, Game Designer: She’s a writer, and she produced plays, and she also invented a way for typewriters to move paper more efficiently.

Patrick Jagoda, Gaming Scholar: I think of Lizzie Magie as a performance artist in some ways. I’m serious, I mean how do you classify her, right? She’s an engineer, she’s a poet, she’s a writer, she’s an activist, she’s a staunch feminist.

Ashlyn Sparrow, Game Designer: She is doing all of these things that a lot of women in that time were not allowed to do, or able to do. She was really pushing boundaries.

Chicago, 1906

Patrick Jagoda, Gaming Scholar: In 1906 she's living in Chicago and she puts out a newspaper ad describing herself as a young woman American slave. The idea is that she's selling herself to the highest bidder and to her dismay people actually put forward offers. But the idea of this is completely performance art. And so, she tried to show how poorly women are paid relative to men and how difficult it is in particular, to be an unmarried woman in America.

Kate Raworth, Economist: She was a social rebel on many fronts and she used shocking performance and play to throw counter-intuitive ideas into society.

Phil Orbanes, Former Parker Brothers Executive: During the Gilded Age, in the 1890s or early 1900s when capitalism was highly unregulated, if you had a dominant position in the marketplace you could dictate price and availability.

Kate Raworth, Economist: These big industrialist, millionaires dominated industries in the US, and they became monopolists in their field.

Phil Orbanes, Former Parker Brothers Executive: And so, people who had it made, the wealthy, employed lots of servants, had lavish homes, and everybody else struggled to get by.

Patrick Jagoda, Gaming Scholar: Lizzie Magie, even in the early 20th century before the Great Depression, is seeing poverty and inequality everywhere. And so much of that poverty is organized around land monopoly: the idea of people being able to own land and extract immense amounts of profits from the working class.

Mary Pilon, Writer: Lizzie Magie sees this income inequality, the rich getting richer and the poor getting poorer, and she becomes an impassioned follower of Henry George.

Mary Pilon, Writer: Henry George was a hugely influential public speaker and thinker of his time. He published a book called Progress and Poverty that was a massive, massive bestseller.

Christopher England, Historian: There's an estimate that as many as five million of his books are sold during his lifetime.

Mary Pilon, Writer: He was really interested in land, landlords, property, ownership and how should that be taxed.

Christopher England, Historian: George, like many people before and after him say, ‘Land's not something anyone's ever made. It's a gift of God. And it belongs to all of us.’

Phil Orbanes, Former Parker Brothers Executive: We think of the American dream as owning a home. Well it was back in the 1890s, but it was out of the reach of most people-they had to rent. And the landlord, according to Henry George, was the devil.

Christopher England, Historian: He sees rent and growing property values as a source of inequality. His solution is what his supporters eventually call “The Single Tax”.

Mary Pilon, Writer: The single tax.

Phil Orbanes, Former Parker Brothers Executive: The single tax

Patrick Jagoda, Gaming Scholar: The single tax.

Patrick Jagoda, Gaming Scholar: This is the Georgist idea that you would tax land at such a high level that it would essentially be communal and nothing else would have to be taxed. For George this wasn’t like an anti-capitalist statement, this was more about fairness. This was more about leveling the playing field.

Kate Raworth, Economist: Lizzie Magie wanted to make Henry George’s point clear. Not everybody’s going to read a political tract. She had a genius idea, she wanted to make it visible through the dynamics of a game.

Patrick Jagoda, Gaming Scholar: In 1904, Lizzie Magie receives the patents, the first patent by a woman for a board game in US history for The Landlord’s Game.

Kate Raworth, Economist: The Landlord’s Game is making a piercing political point and with humor. So she’s got “Lord Blueblood’s Estate”. No Trespassing - Go To Jail. We’ve got a Poor House, Beggerman’s Court, Gee Whiz Railroad, Slam Bang Trolley. Labor upon Mother Earth Produces Wages.

Eric Zimmerman, Game Designer: One of the interesting things about the Landlord’s game is that it has two sets of rules.

Tristan Donovan, Writer: One was to show how evil monopolies were. And in this version players would compete to be the last person standing. Just like present day Monopoly.

Kate Raworth, Economist: But she introduced, along with it, a second set of rules. Instead of paying rent to the landlord who’s property you’ve just landed on, the rent actually goes into the public treasury. Reinvested in the community to create more public goods, public utilities, public education. And of course, this changes everything.

Eric Zimmerman, Game Designer: It, perhaps, deemphasized our traditional pleasures: dominating other players, coming out ahead, being the winner in favor of critical points about how economy and the social fabric is structured and might be structured differently.

Patrick Jagoda, Gaming Scholar: I get why Elizabeth Magie would have wanted to make the Landlord’s game to teach people about the Single Tax. Because games are such a powerful way of internalizing a new set of rules, of practicing it, of experiencing it in a hands-on fashion.

Children Playing Monopoly At A Round Table.

Deacon: One, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight, what’s that?

Ruby: St. Charles Place.

Milo: I own it.

Patrick Jagoda, Gaming Scholar: When we play a game, we sit down for a couple of hours and we enter into a different kind of narrative, a different set of roles, a different series of rules.

Lindsay Grace, Gaming Scholar: The whole idea in playing a game is that you get to experiment with things you may not get to experiment without cost.

Kids playing Monopoly.

Deacon: You’ve been elected chairman of the board. Pay each player fifty dollars?! (Everyone Cheers) Oh lord, ok.

Eric Zimmerman, Game Designer: That’s what play is, play is playing with these structures. It’s not just what happens on the board with the pieces, it’s in the player’s heads and in the social space that kind of ties them all together as they play.

Kids playing Monopoly.

Lula: You need another hundred.

Milo: No, I already gave you the other hundred. You stole my hundred-

Lula: I had two hundreds and then I gave him one and then I was like--realized I owed three so I gave him a five hundred, and he gave me one hundred back and that’s four hundred.

Milo: I passed GO…

Eric Zimmerman, Game Designer: That relationship to me is incredibly powerful that we enter into the system of rules, but then what results is this experience that’s sort of wildly creative and social and chaotic and that’s the emotional experience at play.

Kids playing Monopoly.

Milo: Noo!

Ruby: Oh my god, chill.

Milo: So dang close!

Eric Zimmerman, Game Designer: And I think that Lizzie Magie, like many game designers, recognized the sense of power board games can have on its audience.

Ralph – On The Hunt

Mary Pilon, Writer: The Monopoly Board is an iconic image and it’s design is universal and when you look at Lizzie Magie’s Landlord's game, you see the origins of Monopoly in it. And one of the first things that Ralph Anspach finds when he starts to research who Lizzie Magie was is her 1904 patent. This discovery completely changes Ralph’s case, and he can start to work from that 1904 date and see where did this game go? And that kind of starts the detective story that ends up taking over a lot of Ralph’s life.

San Francisco, CA, 1975

Ralph Anspach, New York City, 2005: The whole thing became a little suspicious, but I got even angrier thinking here’s these guys who seem to have stolen this game and they’re attacking me, when I invented my game, and my game was, you know, was different from their game, and yet they're coming after me.

Mary Pilon, Writer: Ralph is undeterred, he knows that Lizzie Magie had a patent for her Landlord's Game in 1904 and had one renewed in 1924. So how Charles Darrow was able to go in at 1935 and get a patent for Monopoly with his name on it is mysterious.

Mary Pilon, Writer: Ralph and his lawyers put out ads trying to find people who can testify in his case that they played Monopoly prior to 1935. He’s hoping to discover how Lizzie Magie’s Landlord’s Game transformed into the game that we know today. And this has him traveling all over the country and talking to all sorts of people.

Mary Pilon, Writer: He goes into people's homes and they start pulling these boards out of their closets. They hoist them up, this is critical evidence for him.

Ralph Anspach, New York City, 2005: When I uncovered the folk game, the people that were playing on homemade boards and so on, I thought that that was enough to win the lawsuit, but my lawyer said hey Ralph, you’re not there yet because nobody seems to know where Parker Brothers Monopoly came from. So maybe Darrow did invent it from scratch, you never know, sometimes that happens they’re parallel inventions. So, I had one more hurdle to overcome: where does Parker Brothers Darrow’s Monopoly come from?

The Folk Game Evolution

Tristan Donovan, Writer: Until the 1800s, pretty much all board games were folk games, you know, people just passed them down. No one owned them, anyone could do what they like with them just like folk music. That started to change in the 19th century when you have box-packaged, mass produced games. And Monopoly in a way was the very last folk game.

University of Pennsylvania, 1910

Tom Forsyth, Game Historian: Shortly after inventing the Landlord’s Game, Lizzie Magie is starting to share it and some of the people she’s sharing it with are single taxer’s.

Mary Pilon, Writer: One of them is Scott Nearing, this economics professor at the University of Pennsylvania and the game starts spreading on college campuses.

Tristan Donovan, Writer: People started copying it and sharing it. No one is really sure where it came from, no one remembers the names so they call it names like Monopoly, or Finance, or Business.

Mary Pilon, Writer: A few people actually market their versions of the game, in places like Fort Worth, and Indianapolis, and the folk game continues to spread from one community to the next up and down the east coast.

Tristan Donovan, Writer: As it gets spread around, people adapt it to reflect their own interests. One of the first things that gets lost is Magie’s kind of single tax rules.

Tom Forsyth, Game Historian: In the single tax version of the game...again, you got to remember this was not Monopoly, it was the opposite. It was about, not putting wealth in one person, but putting it in the entire community.

Phil Orbanes, Former Parker Brothers Executive: It was boring, of course, to players because players–when you play a game you want to win.

Tom Forsyth, Game Historian: And so Lizzie’s rules for single tax–Georgist type play, just didn’t really catch on.

Tristan Donovan, Writer: But the game is spreading, people keep changing the rules around to suit themselves. And so it actually spent 30 years evolving, just like folk games used to do. Eventually, a Quaker teacher moves to Atlantic City and she introduces it to the local Quaker community there.

Atlantic City, NJ, 1920s

Mary Pilon, Writer: In the late 1920’s the Quakers in Atlantic City were playing the folk game. So they put Atlantic City properties onto the game board. Atlantic City was a very segregated city at that point and the Quakers reflected that too.

Bryant Simon, Historian: Looking at the Monopoly board, the first two properties you confront, Baltic and Mediterranean, which was the segregated black part of town. And perhaps it's not surprising. Those are the cheapest properties on the board. Go to the light blue properties, Oriental Avenue for instance was an area of relatively modest rooming houses. Many of them were places patronized by lower middle-class Jews.

Bryant Simon, Historian: But then as you turn the board and you get to the yellow properties and the green properties, those were always more established, more residential, wealthier parts of town. And then the highest end in Atlantic City is the boardwalk. Here’s where first and second generation immigrants came to show off they’d made it in America by having a black man push them down the boardwalk. We’ve believed this kind of illusion that segregation was a southern phenomenon, but Atlantic city is really a reflection of the larger nation and Park Place and the boardwalk are perfect examples of it.

Mary Pilon, Writer: The changes that the Atlantic City Quaker community make to the board, they’re also creating, inadvertently, this snapshot of race and class in one of America’s most popular vacation destinations in the 1920s.

Tom Forsyth, Game Historian: Ultimately, as Ralph discovers this Atlantic City version of Monopoly, he realizes there is no way that Charles Darrow invented this game.

Ralph Anspach, New York City, 2005: I got a lot of people who played the game before, but no hint of the missing link between the folk game and Parker Brothers Monopoly.

Mary Pilon, Writer: Finally, one of these early players says you know who you really need to talk to is Charles and Olive Todd.

Ralph Anspach, New York City, 2005: A certain Charles Todd. He was the one who introduced a game that was developed by Atlantic City Quakers. He introduced it to Charles Darrow. So I went down to Augusta Georgia and I met Charles Todd and his wife and they told me that something very peculiar happened because they said the Darrows were real pains in the neck.

Mary Pilon, Writer: One evening in the early 1930s, the Todds invite Charles and Esther Darrow to their home for dinner, and at this point, people would make their own boards at home and you would have a Monopoly night.

Tristan Donovan, Writer: The Todd’s introduce the Darrow’s to this game they know called ‘Monopoly’ and the Darrow’s love it. So a few days later Charles Darrow gets in touch and goes…

Mary Pilon, Writer: That Monopoly game was so great, I would love for someone to write down the rules for me.

Ralph Anspach, New York City, 2005: Todd said he wasn’t very enthusiastic, but he did it.

Mary Pilon, Writer: Charles Todd has his secretary write up the rules.

Ralph Anspach, New York City, 2005: So he gave him the rules. Then he didn’t see him for a while.

Tristan Donovan, Writer: All contact ceases. It’s a mystery to the Todd’s, they’re kind of like have we done something to offend them? And then one day, Charles Todd is passing a local bank..

Ralph Anspach, New York City, 2005: He saw an advertisement in a bank.

Tristan Donovan, Writer: And it says, come to this event. Charles Darrow is introducing everyone to his wonderful new game, Monopoly.

Ralph Anspach, New York City, 2005: So Charlie Todd told me he was in a fury. And I asked, well did you ever see the Darrow’s again after that? And he said no, whenever they saw me they would quickly go across the street or walk someplace else, and that’s how Darrow got the game.

Charles Darrow’s Real Story

Mary Pilon, Writer: If you wanted to publish a board game in America, one of the first places you would go to was Parker Brothers, in Salem Massachusetts.

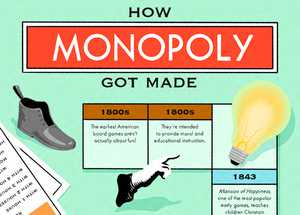

Tristan Donovan, Writer: In the late 19th century, board games were all produced in New England and games, per say, were seen as slightly sinful. Games, certainly for children, had to have a kind of moral element. They had to be a teaching tool, they couldn’t just be for fun.

Phil Orbanes, Former Parker Brothers Executive: The first significant board game published in America was the Mansion of Happiness and it was emblematic of what games were supposed to be - they were moralistic and educational.

Tristan Donovan, Writer: One of the big changes that came along was a guy called George Parker. He started his own game company, Parker Brothers, and his emphasis was on this isn’t an educational tool, this is entertainment.

Mary Pilon, Writer: So, thanks to George Parker's innovation, Parker Brothers become the biggest company in the industry. But not without their share of mistakes, and he was haunted by them.

Phil Orbanes, Former Parker Brothers Executive: In the early 1900s, Parker Brothers decided to license Ping Pong from London and they began to market it in the country.

Patrick Jagoda, Gaming Scholar: And this works for a few years. They’re able to market this as a game that not only men, but women can play. So this becomes a really generalized sort of game.

Phil Orbanes, Former Parker Brothers Executive: Unfortunately for Parker Brothers, it didn't stop anybody else from selling the same equipment under the generic name Table Tennis.

Patrick Jagoda, Gaming Scholar: And this difference between Ping Pong and Table Tennis gets in the way of their market and so they lose a monopoly over Ping Pong. Parker Brothers loses multiple times on huge games. They lose on Ping Pong, they lose on Tiddledy Winks…is that what it's called?

Phil Orbanes, Former Parker Brothers Executive: And so you could not control Ping Pong or Tiddledy Winks and worse, as far as George Parker was concerned, was Mah-Jongg. Many people don't know this, but Mahjong in the 1920s was the biggest game fad ever in America and Parker let that slip away.

Mary Pilon, Writer: By the beginning of The Great Depression, Parker Brothers is not doing well as a company. Robert Barton, who's the son-in-law of George Parker, had just taken over the firm.

Tristan Donovan, Writer: Robert Barton was a capable businessman, but he was in circumstances that were horrendous for any business.

Tom Forsyth, Game Historian: Parker Brothers finds themselves in this really dire situation. They’re laying off employees–they’re actually potentially looking at going bankrupt. And Barton hears about this game out of Philadelphia that’s doing, actually, quite well invented by this local guy named Charles Darrow.

Phil Orbanes, Former Parker Brothers Executive: Charles Darrow in the early 1930s was a heating repair engineer, which meant he fixed steam radiators. But during the Depression, he lost his job, like so many other millions of Americans.

Mary Pilon, Writer: He has a wife and these two children and one of his children has pretty advanced health problems. He needs to be at a special type of school, and the Darrow’s cannot afford it. So he needs money and he needs it very, very fast.

Phil Orbanes, Former Parker Brothers Executive: Charles Darrow begins to make, by hand, copies of Monopoly.

Tom Forsyth, Game Historian: He actually took a round table that he had. The first Monopoly board you see from him is actually a gigantic circle.

Phil Orbanes, Former Parker Brothers Executive: But then he began to automate the process little by little.

Tom Forsyth, Game Historian: Darrow actually hires a professional artist to do the artwork for his board.

Phil Orbanes, Former Parker Brothers Executive: He provided the ‘every man's touch’ to the appearance of the game. A much more pleasant, engaging, simpler look. And so, Charles Darrow made 500 copies in the summer of 1934.

Tristan Donovan, Writer: Essentially he’s self publishing, he’s making a few sets with money he has, selling those, taking the money he’s earned, building some more. Really bootstrapping to make this business work.

Tristan Donovan, Writer: Charles Darrow does go to the big game manufacturers, including Parker Brothers. And he gets rejected at first. They look at the game, and it's a game about mortgages, building houses, and building hotels. It's for the time, a really complicated game.

Tristan Donovan, Writer: So essentially they all say, "No." And eventually he goes to Wanamaker’s in Philadelphia, a big department store, and he persuades them to start stocking the game.

Phil Orbanes, Former Parker Brothers Executive: And that gives Darrow the opportunity to go to a few other stores in Philadelphia and to FAO Schwartz, the leading toy emporium here in New York. By the time Christmas of 1934 has come and gone, Darrow has made 1,000 copies–two print runs and they have sold out.

Tristan Donovan, Writer: It starts selling, and selling, and selling, and eventually, Charles Darrow is making enough sales there for Parker Brothers and other game manufacturers to take a look at Philadelphia and go ‘hmm’.

Mary Pilon, Writer: Robert Barton had already turned Darrow down, but now he invites him to New York City with the intention of buying his game.

Tristan Donovan, Writer: They negotiate to buy the game from him and during this negotiation, Robert Barton asks Charles Darrow, "Is this your game? 100% yours?" And Charles Darrow goes, "Yes, of course." And so they sign it, and start putting out Monopoly.

Phil Orbanes, Former Parker Brothers Executive: Parker Brothers acquires Monopoly in March of 1935, and around June 1st, they’ve moved heaven and earth and they make their first 10,000 print run. And the game sells pretty well.

Tom Forsyth, Game Historian: But the very fact that Monopoly could actually be the hit they’re looking for actually makes Barton nervous. Parker Brothers didn’t want to lose Monopoly the way they had lost Mah-Jongg. I mean, Barton realizes he had to do something.

Patrick Jagoda, Gaming Scholar: Parker Brothers writes a letter to Charles Darrow asking him for his origin story about how he came up with Monopoly.

Mary Pilon, Writer: Darrow writes back, "Dear Mr. Barton, the history of Monopoly is really quite simple…being unemployed at the time and badly needing anything to occupy my time, I made by hand a very crude game for the sole purpose of amusing myself.

Mary Pilon, Writer: “Later, friends called and we played the game, unnamed at that time. One of them asked me to make a copy for him, which I did, charging him four dollars. Friends of his wanted copies and so forth. So much for the outline of the history of Monopoly.” That’s all we get.

Patrick Jagoda, Gaming Scholar: Charles Darrow is a charlatan. (LAUGHS) But for Parker Brothers, it doesn’t matter, if you can sell the origin story to consumers they’re much more likely to accept him as the creator. And because so many people could identify with the Great Depression story and the movement from poverty to riches, the right origin story might just be enough to win the public imagination.

Monopoly In The Depression

Patrick Jagoda, Gaming Scholar: It's remarkable that this game took off on the back end of the Great Depression. Why would people want to play a game about accumulating wealth after most of them had lived in abject poverty for years? I think part of the reason is wish fulfillment. What better fantasy to have during and after the Great Depression than being able to be in a position of power and being able to accumulate mass wealth, when you know you'll never be able to do that in your own life.

Ashlyn Sparrow, Game Designer: Monopoly is a quintessential American game by virtue of how it plays. Everyone, regardless of your race, religion, or creed starts off with the same amount of money.

Lindsay Grace, Gaming Scholar: Everybody has a fair chance, everyone collects $200 when they pass go, everyone has the opportunity to purchase, all of these things are baked in.

Kate Raworth, Economist: Monopoly creates a very false sense of ‘well we all started off equally, if I’ve got ahead it must be my skill it must be my hard work.’

Archival of men playing Monopoly.

“I got you John. That’ll be a hundred dollars.”

Kate Raworth, Economist: When actually in real life, we do not start on that same starting line.

Ashlyn Sparrow, Game Designer: Monopoly makes it easy to imagine that you can accomplish your goals, accomplish your vision, you can start a business and you don’t have to think about what you look like, where you come from, that you’re from a different class, from a different race, have a different gender, have a different gender expression–you don’t have to think about any of that at all. Right? And that is the problem and the myth that Monopoly continues to just push forward.

The Monopolization of Monopoly

New York City, 1936

Tristan Donovan, Writer: Monopoly becomes an instant success. The orders flood in. They can’t make games fast enough, they put on extra shifts in their factory and they still can’t catch up. It’s one of those games that just hits at the right moment and suddenly everyone wants one.

Phil Orbanes, Former Parker Brothers Executive: In 1936, the game went from a quarter of a million to nearly 1.8 million, which literally was the maximum number of games that Parker Brothers could make, even mobilizing the entirety of Salem Massachusetts to help.

Tristan Donovan, Writer: It's the biggest success the board game industry has ever seen.

Tristan Donovan, Writer: And then one day, Parker Brother’s lawyer rushes into Barton’s office and goes, ‘There’s a game just like Monopoly called Finance. And actually there’s another game that is just like it as well and another game’ and suddenly he’s in a position where he thought he had the biggest hit ever and had the rights to it and now it’s pretty obvious that Charles Darrow has copied this game.

Mary Pilon, Writer: Robert Barton has a problem. The thing that is saving his company from bankruptcy, Monopoly, that is this runaway hit was not invented by Darrow. He needs to protect Monopoly at all costs

Phil Orbanes, Former Parker Brothers Executive: And so Robert Barton, attorney by trade, decides he has to own every game that's remotely similar to Monopoly.

Mary Pilon, Writer: He needs to get control of these other competing games. Finance, Easy Money, Inflation. But Barton has another problem, and that is Lizzie Magie.

D.C. in the 1930s

Mary Pilon, Writer: At this point, Lizzie Magie is married and working as a secretary in Washington D.C. We don’t know if she realized that the Landlord’s Game had been spreading, but we do know by 1935, the Darrow story starts to take off.

Tom Forsyth, Game Historian: Lizzie is reading about this inventor Charles Darrow and she actually goes to the press and says, ‘Wait a second, that’s my game’ you know, ‘that’s my invention’.

Tristan Donovan, Writer: For Parker Brothers, this is a complete disaster. And so Parker Brothers decides it needs to shut this down. It needs to preserve Charles Darrow's story.

Mary Pilon, Writer: So, George Parker comes from retirement in a very dramatic fashion and he takes a train to Washington, D.C.

Tristan Donovan, Writer: George Parker is quite elderly at this point and he goes to Lizzie Magie to sweet talk her into selling the rights.

Mary Pilon, Writer: He says, "We, Parker Brothers, are going to publish your Landlord's Game and two other games of yours."

Tristan Donovan, Writer: We’ll put your picture on the front of these boxes and talk about you as an originator of board games.

Mary Pilon, Writer: And she thinks, ‘Wow, my Georgist teaching tools are going to be front and center with one of the biggest game companies in the world.’

Tristan Donovan, Writer: She kind of figures well no one paid any attention to the Landlord’s Game before. Maybe this is a chance to revive interest in single tax. So for $500 she signs over the rights.

Kate Raworth, Economist: They pay her five hundred dollars.

Patrick Jagoda, Gaming Scholar: Five hundred dollars.

Mary Pilon, Writer: Five hundred dollars. And Parker Brothers acquires the rights to her game.

Tom Forsyth, Game Historian: This is the great irony of it all. Parker Brothers comes in and monopolizes Monopoly and Lizzie, she’s that kid sitting on the sideline of Monopoly who just got taken out of the game.

Mary Pilon, Writer: Per the terms of their agreement, Parker Brothers released The Landlord's Game and two other Lizzie Magie titles, but did little to publicize them and they didn’t sell well. Then, when they release the new version of The Landlord’s Game, it bears no resemblance to the original. Even worse, she discovers that Parker Brothers took advantage of the fine print in their contract, which gave them editorial control and they published the game with only one set of rules, omitting the single tax version. Finally, two years later, when her patent expires for good, they erase her from the history of the game and betray her again. Any acknowledgement of her in the press or that she had any role in the game is very, very quickly lost to history.

Kate Raworth, Economist: She was hanging onto the belief that Parker Brother’s would now finally publish her game. They would print her face on the cover of the board. And so they say, ‘There you are, Lizzie. There's your face. You see, we've acknowledged you as the inventor of the game, but we'll just let that addition quietly slip.’ And so, they flatter her into insignificance.

Patrick Jagoda, Gaming Scholar: Magie makes $500, Darrow makes over a million dollars. Not exactly fair.

Mary Pilon, Writer: One of the last traces we have of Lizzie Magie’s life is the 1940 US Census. What’s interesting about that census is that she died in 1948 so it’s the last one she would have been able to participate in. And she lists her occupation as maker of games and her income as 0.

San Francisco, CA

Tristan Donovan, Writer: By the late 1970s, the Anti-Monopoly case has dragged on for years. Ralph is on the verge of ruin. It’s not like he’s a rich man. He’s, kind of, there scraping it together paying lawyers, paying court fees, trying to fight this Goliath.

Tom Forsyth, Game Historian: It’s not just Ralph’s case. His son, Mark, had helped him to design the game and his wife, Ruth, was busy running the company and so it’s really taking a toll on his whole family.

Ralph Anspach, New York City, 2005: We were in real financial trouble. We had three mortgages on our home. And one of the mortgage holders was about to foreclose on us.

Mary Pilon, Writer: He takes out loans on his home, these second mortgages, which is, when you think about Monopoly–very ironic. So he’s just completely worn down in every sense.

Tristan Donovan, Writer: And then on the eve of the court case, lawyers inside General Mills and Parker Brothers make Ralph an offer.

Mary Pilon, Writer: And it’s big. It’s a good one.

Tristan Donovan, Writer: Equivalent of more than 2 million dollars.

Mary Pilon, Writer: There’s just one catch, he’s not allowed to talk about the game's origins.

Tristan Donovan, Writer: And Ralph says no. He’s come this far, he’s going to see it out.

Ralph Anspach, New York City, 2005: People said you’re crazy, take the money and run to the bank, but I just can't live with myself if I cave in.

Mary Pilon, Writer: This was about something beyond money. This was about proving a story, proving a case, that was not something that was up for sale at any price for him.

Tristan Donovan, Writer: Ralph now has the evidence of how the board game changed over the years and he doesn’t just want to be paid off and to let Parker Brothers carry on as before. He wants to win.

Mary Pilon, Writer: Ralph and his attorney’s are trying to prove that the Monopoly patent itself is fraudulent. And that’s a pretty scandalous thing to be alleging at this time. You have to remember that when this case was coming about in the mid-1970s, the Monopoly story hadn’t really been challenged and certainly not to this extent and where the stakes were so high.

Exterior of US District Court, San Francisco, 1970s

Mary Pilon, Writer: So for this trial, Ralph calls upon nine of the folk game players. These folk players testify to playing the game before 1935. So it goes from rumor to record.

Archival sound of the testimonies

“Now, Mr. Harvey, did you ever play a real estate trading game?”

“Yes.”

“And what year did you first play such a game, sir?”

“I would say it was nineteen…thirty-one.”

“I had a Quaker friend at Smith and I went to visit her in the spring of 1922. We played it all the time.”

“I was at MIT. I copied theirs. That’s the way it went, from one person to another.”

“Do you have a name to the game?”

“It was called Monopoly.”

“Monopoly.”

“Monopoly.”

“They were all playing Monopoly.”

Ralph Anspach, New York City, 2005: We had them…you know, we had them over a barrel now. Because they were sitting there with a game that seemed to have been stolen. We were really quite confident we were going to win.

Mary Pilon, Writer: So they go through this whole trial and the judge issues a ruling and it is not good. But I think we have to be realistic, this was a David vs. Goliath story, and Ralph’s judge generally ruled on Goliath’s side.

Tristan Donovan, Writer: The judge rules in Parker Brothers favor. It says, ‘you must not put out Anti-Monopoly’ and for Ralph this is an absolute disaster. I mean, this is ruin. He’s not only lost his game, he won’t get court costs, he won’t get anything.

Ralph Anspach, New York City, 2005: That was it. We were finished. I remember I was terribly depressed. We lost the case. The judge ordered us to turn over all our games to Parker Brothers. Then Parker Brothers did something which is not usually done, but Parker Brothers was determined to teach others a lesson.

Mary Pilon, Writer: Part of the ruling is that Ralph has to hand over his Anti-Monopoly games. Parker Brothers take these games and they’re in Mankato, Minnesota, which is not far from where they're being manufactured.

Ralph Anspach, New York City, 2005: 40,000 of our games were literally buried in Minnesota with a national story describing this. This is what happens to people who challenge this great company and this great game.

Mary Pilon, Writer: Ralph later told me, something to the effect of, it felt like they were dumping me in the trash.

Ralph Anspach, New York City, 2005: I just couldn’t face it. I couldn’t face to see these games turned into trash, you know? I couldn’t…I didn’t have the courage to see that.

Cut to kids playing Monopoly.

Ruby: Is it your turn? Or…Lula’s?

Soren: It’s Lula’s.

*Kids cheering*

Milo: No!

Lula: Yes!

Soren: Why are you happy?

Patrick Jagoda, Gaming Scholar: I think the competition of Monopoly is quintessentially American. Monopoly might not be the perfect game for teaching people about economics, but it's a really great way of training people's emotions to be aligned with competition, of wanting competition, wanting victory.

Cut back to kids playing Monopoly.

Milo: Believe in the dice…*rolls dice*

Lindsay Grace, Gaming Scholar: Monopoly claims that there is a sort of right way to win that means some other people are going to have to lose.

Cut back to kids playing Monopoly.

Soren: How much is that?

Ruby: 1,200.

Soren: Well, I don’t have enough so whatever.

Ruby: You’re bankrupt, you’re out.

Soren: Yeah, I know.

Lula: Bye!

Soren: Why!

Kate Raworth, Economist: Why is this game, the game that we remember and loved and wanted to play? And the traits it brings out are ruthlessness, greed, acquisition, accumulation, no pity for your opponent. And the irony is that we’re drawn to playing it.

Cut back to kids playing Monopoly.

Milo: I have the most money!

Lindsay Grace, Gaming Scholar: It is a zero sum game. And so, the kind of rhetoric there is that there can be only one victor. And I think that’s an interesting metaphor, the way that our capitalist system works in the United States.

Cut back to kids playing Monopoly.

Soren: You got lucky.

San Francisco, CA, early 1980s.

Mary Pilon, Writer: After his defeat, Ralph is determined to keep fighting. He appeals, and it takes another six years for his case to go through the legal system, until there is only one place left to go.

Mary Pilon, Writer: Ralph gets on a train to Washington, D.C. He’s got all of his legal papers with him, and he walks them himself to the Supreme Court. And that’s kind of an amazing moment because when you think about–here’s Ralph, this guy who ten years ago is making a game called Anti-Monopoly and gets a cease and desist at his doorstep about a board game, now finds himself appealing for his right to make these games at the Supreme Court of The United States.

Tristan Donovan, Writer: And when it comes down to the Supreme Court’s decision…they back Ralph.

Archival: Dan Rather reports on Ralph’s victory.

Rather: The makers of the popular board game, Monopoly, today drew a chance card and lost. For real. They didn’t go to jail, they didn’t pass ‘Go’, but lost their monopoly on Monopoly.

Mary Pilon, Writer: Ralph, pretty much, wins it all. He gets a significant lump of money.

Tristan Donovan, Writer: Parker Brothers has to repay him for all the copies of the game they destroyed, and cover his court costs, and pay him damages.

Mary Pilon, Writer: He wins his right to produce Anti-Monopoly and to keep making his games, but he also wins the right to talk about the game’s history and its origins openly. That, for him, is a huge, huge win because at this point he had been talking about the game for a decade, but he wanted to keep telling the story of Lizzie Magie, Darrow, and what really happened.

Ralph Anspach, New York City, 2005: Most people thought that I was crazy. And, of course, I felt very vindicated. Because, you know, it was a long struggle, but I was determined to accomplish my goals regardless of all the opposition and so on. And maybe the…maybe the idea that there is something else in the story. Namely…the little guy can win out sometimes and overcome.

Ralph Anspach, New York City, 2005: Monopoly is more than a game. It's a commentary on both what’s great and what’s dark about our business empires.

Patrick Jagoda, Gaming Scholar: Is anything just a game in American society? When games are the one of the most popular cultural forms that we have. When they train us in so many norms and ideas that we move outside of the game space, can we say that something is just a game?

Mary Pilon, Writer: Monopoly is tied to so much history and so many memories for people that it belongs to everybody, but I think that the myth of Monopoly does obscure a lot of realities about this country about class, about race, about gender, about how our current, dare I say, game of capitalism is played and has been for centuries. So it ends up becoming this microcosm of the bigger story of this country and how we perceive it now and look back on it.

Bryant Simon, Historian: It’s an interesting question if Monopoly creates a misguided view about the United States. And maybe the way to think about it is, what if the original game had caught on? Would that have paved the way for an alternative political vision of America? That puts a lot on a game, but I think capitalists have always wanted to tell a story about how, in America, some people get ahead and other people fall behind and that’s either luck, that’s the roll of the dice, that’s because they didn't play the game the right way…it’s just like Monopoly.

Dice landing on the board.

Ruthless: Monopoly's Secret History

Ruthless: Monopoly's Secret History