In October 1967, history turned a corner.

In a jungle in Vietnam, a Viet Cong ambush nearly wiped out an American battalion, prompting some in power to question whether the war might be unwinnable.

On a campus in Wisconsin, an antiwar demonstration spiraled out of control, marking the first time that a student protest had turned violent.

These two simultaneous events, half a world apart, offer a window onto a moment that divided a nation and a war that continues to haunt us.

Jane Brotman, Student: I was very proud to be an American. I felt like this was the greatest country in the history of the world.

Joe Costello, Private: I volunteered for the draft. It was an escape for me to avoid attending college.

Mike Troyer, Private: My granddad fought in a war. My father fought in a war. This is what you were supposed to do if they wanted you. So that's what you did, even though it was wrong. You had no choice in it.

Mark Greenside, Student: I'm the first-born Jewish son after the Holocaust. You don't just blindly follow; you don't just blindly obey. You stand up when you see something wrong. Your government like any other government can make mistakes.

Diane Sikorski: Danny and I grew up in Milwaukee. People in our neighborhoods didn't go to college. You graduated and you got your diploma from high school and you got a full time job.

Jim Rowen, Student: I lost my student deferment, and I remember staying in a barracks. And the boy who was on the upper bunk, he looked to be like 17 and a half. I couldn't even believe he was draft age. And he cried all night for his mother. And I felt horrible about that. And the only thing I felt I could do was to simply work harder to stop the war.

Clark Welch, Commander of Delta Company: Vietnam is an oppressed people that needs liberating. It's what I've trained for all my adult life. It's why I was in the Boy Scouts, trustworthy, loyal, helpful, friendly, all of that stuff was just a, of course, I'll go to Vietnam. And for somebody to say that it's wrong to liberate the oppressed -- that don't make sense. It was just so simple, so simple -- not so simple now.

Mike Troyer: We were informed that we were going to be in the Black Lions special unit. And they told us all about it and how that Charlie was really scared of us. They had us pumped up to the fact that we thought that we were invincible. You know, you were 20 years old and you were bulletproof. Well, maybe. Basically, I don't think I gave a [expletive] about communism. Hey, we're fighting Communism, I don't care if you're fighting against flamenco dancers, okay? We're going to do whatever the government says -- they own me, I got to do it.

Ernie Buentiempo, Private: I was older. I was 23-years-old, but the majority of the people that were there, the kids, you know, to me they were kids -- 18, 19, cherry boys, some of them hadn't ever been with a woman.

Tom Hinger, Medic: These were some great guys. They become your whole world. They're more important to you, at that time, than your family, because you know that they're going to be with you tomorrow.

Clark Welch: We trained hard, hard, hard. I taught a lot of the classes myself. They were good, and they were bright. It was like I didn't want to go to sleep at night and, when I would sleep, I'd wake up thinking, "Jesus [expletive], here's something we could have added." The first day when you're standing there and it starts to rain and you see some shuffling around, like, "Wait a minute, what do you guys think we're going to go inside? What the hell's wrong with you?" It's raining. So what? That develops into you've been shot in the arm. So what? Uh, your buddy's been killed. So what? They got better and better and better. I was so [expletive] damn proud of them. All I wanted to do was make a better company. All I wanted to do was make a better company.

Clark Welch, read from letter: My Lacy, Everyday I can see my company get better and better. There's been quite a shift of people in our battalion. No one has thought too much of our battalion commander, and last night he finally got relieved. Lt. Colonel Allen is our commander now. As far as I know, he seems like a fine man.

Jim Shelton, Major: I said, "You're not any relation to General Terry Allen are you? And he says, "Yeah, I'm his son." And I just was absolutely flabbergasted by that. General Terry Allen, he was on the cover of Time magazine.

Consuelo Allen, daughter of Terry Allen Jr.: It was very clear that my dad wanted nothing more than to be a general like his dad was.

Jean Ponder Allen: He very much wanted his father to be proud of him. I encouraged this. I very much wanted to be a general's wife. When I first met Terry I was 18, so he would have been 31. It was very prestigious to marry into the Allen family. And in El Paso there was no question that the war in Vietnam was a good thing, and we would go over, and we would whip them, and we would come back. And to me Vietnam meant, especially, that this was Terry's opportunity to have combat duty; that was really the sum total of it in my own mind.

Paul Soglin, Student: When we returned to school in the fall of '67, a lot of things had changed since the spring. The war had picked up considerably.

Jim Rowen: People were getting angrier and angrier and angrier about the war and the draft and the news that they were seeing, the images on television, the level of violence, the body counts, the bombings. It was all mounting.

News Anchor, archival footage: In the week ended last Saturday, 171 Americans were killed in combat, 977 were wounded.

Walter Cronkite, archival footage: One hundred and ninety-three Americans died in combat last week.

Walter Cronkite, archival footage: Number of American killed in combat in Vietnam is now over 14,000.

Jack Cipperly, assistant dean: More and more people were trying to make a decision about where they would stand in relation to Vietnam. I was aware for the first time that there was a beginning of some kind of a movement. It was kind of mystifying and it was also a bit threatening to me, because I thought, "What's going to happen here?"

Jane Brotman: Everyone was trying to get your attention, and one might be, you know, a petition to sign against the war in Vietnam. And, you know, I had very suspicious feelings of these folks. If my government said we needed to be in Vietnam, then I believed we needed to be in Vietnam.

Paul Soglin: I remember a group of us gathering and looking at the Daily Cardinal and seeing that Dow was coming to campus to recruit, which prompted a discussion that we had to start preparing for that.

Ned Brandt, Dow publicist: The best known product that Dow was making was saran wrap. The Dow company began making Napalm in 1965. The board chairmen, the CEO, had served in the armed services in World War II. That made it rather natural that when your government wanted you to make some, some stuff, even though it was very nasty stuff, that you made it without any question.

Mark Greenside: Napalm was this hideous, jellied gas burning at 2,000 degrees Fahrenheit. It didn't just kill you; it tortured you. It has a complete reference to Zyclon-B, the gas they used in the concentration camps. It felt like chemical warfare at its worst.

David Maraniss, Author, They Marched into Sunlight: Napalm was the symbol of the war. A year earlier there had been a huge story in Ramparts magazine talking about the effects that Napalm had on what it said were millions of children in Vietnam who had been burned by it.

Maurice Zeitlin, Professor: The horror of napalm made an indelible impression on all of us and especially on students when they discovered that the University of Wisconsin had invited Dow Chemical Company to come to the campus to recruit. And the man who was to become the Chancellor of the University shortly thereafter, William Sewell, he said why can't they go and recruit off campus like they do in most places?

David Maraniss: Sewell was an opponent of the Vietnam war. He'd voted against allowing Dow to recruit on campus but he was outvoted.

Maurice Zeitlin: The faculty endorsed their right to recruit, and the response of students who cared was that they had to do something if the faculty was not going to take a reasonable stand on this.

Paul Soglin: People want to go work for Dow that's their business, however, to use the University buildings to, in effect, provide a subsidy to Dow, by providing them the space, we thought was absolutely wrong.

Jim Rowen: I didn't want to see any more Vietnamese children running around with their clothes burned off. There were millions of us who thought that if we put in enough time and made enough noise that it would make it impossible for the government to keep sending young men to Vietnam.

David Maraniss: In the fall of 1967, there were nearly a half million American troops in Vietnam. General Westmoreland, the commanding general, wanted another hundred thousand or more, thinking that they could win the war through battles of attrition. Lyndon Johnson wanted body counts, and the pressure was flowing down on all of theses battalions like the Black Lions battalion, to just go out into the jungle, search out the Viet Cong and destroy them.

Jim Shelton: We had some intelligence that a VC division were in this area. And so around the tenth of October the Black Lions were sent back out, Terry Allen in command, and it was an exciting day.

Tom Hinger: You would be out searching for base camps, searching for the enemy, and then at night you would come back to what was called a night defensive position.

Bud Barrow, First Sergeant: We moved from one Night Defensive Position to another. And it seemed like everyday we made contact of some kind, maybe 2 or 3 people, maybe just a couple of rounds, sniper or something you know...

Ernie Buentiempo: There was movement all around us. You could just sense it in the air. You just get goose bumps.

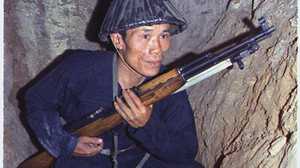

Gerald Thompson, Sergeant: I live in the hills of east Tennessee. You don't come in my backyard and sneak up on me. I know every nook and every cranny. I know the creeks. You ain't gonna sneak up on me in the woods in my home town. You're not going in the jungles of Vietnam and sneak up on a VC. He knows where you're at. He knows where you're at before you ever leave base camp.

Clark Welch: My company was getting most of the action, because I would go where the enemy was. I had a good feel for what the enemy was doing, but we were finding the enemy. I couldn't have dreamed that it was the entire regiment.

Vo Minh Triet, Colonel, North Vietnamese Army: My regiment had 1200 soldiers. We weren't supposed to engage in any battles there. We were just passing through on our way to another mission. But we'd had no rice to eat for days. We heard if we came to this area, they might have rice. But when we got there on October 15, we found that this unit had no rice for us either. They told us to wait a few days. We dug bunkers in case of attack. If we had found rice in that area, then we would have left that area on the 16th and none of the fighting would have taken place.

Bert Quint, archival footage: It's a big hot murderous jungle and somewhere in here are hundreds, maybe thousands of Communist troops. In the last couple of days, American soldiers have come in looking for them, spoiling for a fight.

Jim Shelton: There was a feeling from General Westmoreland all the way on down, like we were doing an awful lot of work and not getting much return. We had a hard time having big fights. We thought we were doing that, but the enemy wasn't fighting.

Bert Quint, archival footage: Where is the enemy, General?

General Hay, archival footage: Well I think right now they're North of us, and some on the West, but we'll find them, don't you worry about it.

David Maraniss: General Hay, the commanding general, was being told by Westmoreland that he wasn't aggressive enough. So Hay, in turn, was putting pressure on his commanders like Terry Allen to go chase down the Viet Cong.

Jim Shelton: Terry Allen knew that the purpose for him being in there was to make contact and beat 'em up.

Tom Hinger: The company commanders are encouraging the platoon leader to get the platoon moving. And the battalion commander is encouraging the company commander to get his company moving faster.

Gerald Thompson: Colonel Allen, he's up there flying around in a little bubble-chopper, and he'd say "pick up the pace, you're going to slow." And you're carrying 50 pound packs, and not knowing when somebody's going to ambush you.

Mike Troyer: He was mad because we weren't going through the jungle fast enough. Well, get your big ass out of that helicopter and come down here and try it.

Jim Shelton: Terry Allen certainly felt the pressure of battalion command. The guy before him had been relieved of command. And he certainly didn't want to get relieved of command. By this time, we had become confidants, you know what I mean? He was telling me stuff that he was thinking about. He did tell me that he had gone home to try to patch up his marriage.

Jean Ponder Allen: When Terry left to go to war in Vietnam, I set about trying to build some kind of a life for myself in his absence. I didn't know, really, what it meant to be the wife of somebody in the Army. It's an incredibly challenging way to live. All of a sudden, you are in a house alone. Assumptions that I had never questioned were being challenged. I was being assaulted by these images, what was being shown on television every night in the nightly news. The bloody combat, the body bags that were coming back, shots of protestors in other parts of the country. And, all of a sudden, there was a whole new dimension to the war in Vietnam that was opened up to me. It was shattering. It felt as though I had been living a lie. And it did seem like a huge backdrop of Disneyland had all of a sudden been ripped apart, and in its place you saw women and children and soldiers on both sides being blown up and body parts and blood and body bags and people crying. And you had to ask, "What is my role in this? What have I done or what am I doing that is keeping this going? How am I contributing to this devastation?" And so I began to doubt what it meant to be a military wife. And, on a more personal level, I began to have serious doubts about our own marriage. And so I did write him a letter, I believe classically known as a "Dear John" letter, saying that I didn't want to be his wife anymore.

Jim Shelton: Terry said, "I, I don't, I don't want to be divorced from her, I love her." He had gone home to talk to his wife.

Jean Ponder Allen: I had committed myself so far by my actions that it was impossible for me to turn back. And so I told him that it just wasn't any good, that I was going to go ahead with divorce proceedings.

Consuelo Allen: I have a memory of what I understand now was the last day we spent together before he left the next morning. He came through the door and he came to find us, and I can remember just saying "You can't go. You just, don't leave us, just please don't leave us." And I can remember that I said to him, "I, I'm afraid you're going to die, I think you're going to die." And uh, and then he left.

Jim Shelton: On the sixteenth of October, Delta and Bravo Companies went into an area where they thought they were going to make contact and they did.

Clark Welch: It was beautiful. The firing was perfect -- everything was just perfect, perfect, perfect. We're beginning to see more enemy and the bunkers that had been very carefully camouflaged, when you fire at them with machine guns, it knocks the stuff away. It became clear that we were on the edge of a base camp.

Jim Shelton: Now, we didn't know how many were in there, but we knew that we were getting to a vital organ, if you will.

David Maraniss: On October 16, General Hay and several of his brigade commanders meet with Terry Allen in the field, and Terry Allen's bosses essentially told him, "We've got the Viet Cong where we want them. Get your ass on the ground with your troops."

Clark Welch: There was a full moon that night. I remember the full moon. And went to the tent where the briefing was. Colonel Allen said, "This is going to be a great day for the Black Lions. Tomorrow we're gonna get 'em." And then the colonel said, "This is what we're going to do tomorrow: Delta Company will lead." Eh, eh, yeah. "Alpha Company will follow and we're going to follow this route." It's a frontal attack on a fortified position. You don't ever do that.

Jim George, Alpha Company Commander: One of the cardinal rules in tactics, especially in that kind of environment, is you don't go out the same way two times, because the enemy will be waiting on you in an ambush.

Clark Welch: I certainly didn't say, "Colonel, that's [expletive] damned asinine." I think I said something like, "What?"

Bud Barrow: Lieutenant Welch said, "Sir," he said, "I believe, I don't think we should go out there tomorrow with just the two companies because," he said, "there, eh, there's quite a bit out there," he said, eh, eh, eh, "they may be a lot more enemy there than we suspect." Colonel Allen said, "Ah, Welch," he said, "You're just gun shy." Well, this really tore up our Company Commander, you know.

Clark Welch: Worst moment of my life -- Colonel Allen said something about if Welch is gun shy, we'll have Alpha lead. And he used that word, I believe, gun shy, not coward, but gun shy. And Alpha Company commander who is right here, Jim George: "Okay." He, he'd never, he'd never, been in a fight.

Jim George: The deal in the army is that you go into a meeting, you state your disagreement, but when the boss says, "This is the way it's gonna be done" -- when the meeting's over, all the subordinates walk out and say, "This is the way we're gonna do it."

Clark Welch: And it just was no, no communication, there was no, we didn't have a discussion, there's no communication. And I said, "Alright sir, Black Lions."

Student with megaphone, archival footage: Dow produces napalm. And I ask you to think it over, to go to your newspapers. Explain what your position is. They don't understand you. They don't understand what kind of weapon this is.

Paul Soglin: It gets back to the question of do we have a responsibility to stand up at some point and say "Wait, no, this is wrong and if we say no enough times in these instances, maybe we can have an effect."

Jim Rowen: This demonstration was going to be different. There was going to be an escalation of tactics, and an escalation of personal risk. The goal was to obstruct the recruitment, by Dow, of students who were looking for jobs after graduation. And we knew that that was a violation of the law. You might end up in jail. You could find yourself expelled from school and in those days, you know, expulsion from school could be a ticket to the war.

Jack Cipperly: We knew of course there was going to be a demonstration in the Commerce Building. But I think there was a strong feeling that, well, if they want to block it, let's just let them block it for a while and see if we can wait them out. I did notice that there were some legislators over on the side observing this and I thought to myself, this is not going to go down well with them. And I felt that there was going to be a reckoning at some time in the future.

Maurice Zeitlin: The University of Wisconsin was a short walk from the state capitol, where the legislature and the governor met daily. Governor Knowles was on the telephone excoriating the Chancellor of the University, William Sewell, for not taking action against these disruptive students.

Jack Cipperly: There was sort of an unwritten expectation that Madison Police would take care of patrolling Madison, and University of Wisconsin police officers would take care of the campus.

David Maraniss: Most of the city cops were from the east side of Madison, the working class side of town. To them, the university on the west side was a foreign world.

Keith Hackett, Madison Police: We would run into students on State Street where a person like me, who was from a farming community, would begin to realize that there was a different, different society out there, as far as students. A lot of them from the East Coast, a lot of money, new cars, nothing they couldn't buy.

Tom McCarthy, Madison Police: I used to ride the bus to work and there was this one guy who would get on the bus and he would just condemn and scream and holler about the government and about how mean they were. And I just looked at him and I said, "You know, if they ever wanted to drop the atom bomb as a test, they could drop it right on top of the university and I wouldn't give a [expletive]." He never said another word.

Keith Hackett: They were young and dumb. And they didn't really have any idea what they were doing and they thought this was a way for them to show their patriotism, and it wasn't. If you want to run this by anarchy, which is what they were trying to do, then you have a fight on your hands.

Vo Minh Triet: B-52s dropped bombs that night, so I knew they'd attack the next morning. Where I was, there was one lone tree left standing. On this tree, a monkey kept climbing up and then halfway down the tree. The soldiers asked for permission to shoot the monkey, because they hadn't eaten for five days. I thought of the monkey, how similar its situation was to ours. It just wanted to live, like us. I ordered the soldiers not to shoot it.

Clark Welch: When we came in for breakfast that morning, I would say you're going to be in a big fight today. You got plenty of ammunition? "Oh, yes, Sir. Yes, Sir, Black Lions, Black Lions."

Mike Troyer: Well, they told us we were going to a place that was going to be pretty rough and that's all. They didn't tell us what was waiting on us. You had no choice; you just went.

Clark Welch: I do not believe that Colonel Allen had ever moved with a Command Group on the ground until the 17th. And he showed up with, I think, 13 people -- Jesus [expletive]!

Mike Troyer: Alpha Company was leading, and right behind Alpha Company was Delta Company. There was like a hundred and thirty of us, and I thought well this is one of the biggest forces we've ever sent out. There's no way they're going to mess with us.

Vo Minh Triet: The battalion commanders had scouts who would climb the high trees. They would observe the enemy and report back. They'd tap the trees to let me know they received my orders. We let the enemy approach, coming in close until they were in firing range.

Mike Arias, Private: I happened to see a tree move to my left front. I don't remember who was sitting behind me, but I did tap him on his shoulder and I pointed to the tree and I took my M-16 and I put it on automatic, and then he looked at it and he goes "Oh, there's nothing there."

Tom Hinger: Suddenly, there was this series of clicking sounds, and then the battle started. It sounded like every weapon in the world was being fired at that point from, from all directions on us.

Ernie Buentiempo: I saw Breeden fall, I saw Carrasco fall, and I saw Gribble fall.

Bud Barrow: We heard a lot of fire ahead of us, which we knew was Alpha Company.

Mike Troyer: They were firing out of the trees. They were firing out of bunkers. All you could shoot at was muzzle flashes.

Jim Shelton: We had 160 men and they had 1,400 men, okay? Ten to one. It was ten to one.

Vo Minh Triet: We had more soldiers than they did, but we didn't have the same firepower. We would fight very close to them, only ten or fifteen meters away. When we stayed close to them, they couldn't bomb us.

Ernie Buentiempo: Within a few minutes, I guess whatever I couldn't tell, a huge claymore mine went off. It hit Farrow, hit Sergeant Johnson who was laying next to me. To this day I see him. [SIGHS] He was just laying there in blood.

Clark Welch: Alpha Company disappeared. And now the firing was directed against us, against Delta Company.

Vo Minh Triet: At that point, we brought in the third battalion, so we had the enemy on three sides.

Clark Welch: But it was the second bunch of firing that started killing my guys. And when I came back to see Colonel Allen, I said "Do something!" You know, "Bring artillery, give me the artillery! Give me the command! Give me something!" I thought about the, the "Mutiny on the Bounty" there, that, that ran through my mind that, you know, should I take over?

Bud Barrow: But they was coming right in on us. I seen one run up to one of our machine gunners and blow a claymore mine.

Clark Welch: Sikorski, our machine gunner's dead. "Somebody else get the gun, get the gun." I didn't give him that much time. Too many people were dead, too many people were wounded, I could not, I couldn't even have run away because that would have left Alpha Company's dead and wounded.

Bud Barrow: Lieutenant Welch -- he was moving around among the people, telling them where to fire. I seen him get hit, at least two times, and I seen him fall a couple of times and he'd get right back up.

Clark Welch: It's good for the men to see that you're up and moving because if you're cowering down it makes them think it's really bad. And I came to the Colonel and he's looking at a picture. And my words to him were, "What the hell are you doing looking at a picture? And I'm gonna fire artillery..." And then he said, "No, you can't fire artillery because Alpha's the lead." "Sir, Alpha Company is gone. I'm firing." And a bullet came overhead and hit him, right in the helmet, but it just blew the top part of his head away. And when he fell forward he fell like that, and I could then see that it was a picture of the three little girls.

Mike Troyer: Anybody that was in the shade was safe. Anybody that was in the sunshine was getting shot.

Tom Colburn, Private: I can't remember his last name, but he's looking at me, you know, saying, reaching out saying, "Help me, help me." And every time he tried to move to get some cover, they'd, they'd shoot him. If I got over the fear and felt more braver, I probably could have ran out there and saved his life, you know. Be like Superman, you know? Just run out, grab him, pull him back. And all of a sudden they disappeared. It was all over, I mean, it was g-they were gone.

Vo Minh Triet: When the enemy attacked, we had no choice but to fight them. But we were late for our next battle. So we left.

Mike Troyer: I went through I don't know how many different bodies, crawling around out there, trying to find somebody that was alive. I mean there were people with no faces, arm, legs missing.

Clark Welch: I was there when the firing stopped. I do not know when I became unconscious the final time.

Bud Barrow: I looked around and everything was just dead silence. It was just such a lonely feeling. But there was no noise, and I remembered hollering, "Can anybody hear me?" And after I hollered that a couple of times I heard someone off a short, a short distance away said, "Yeah, we're over here." Said, "Who is it?" And I told him, I said, "This is First Ser-First Sergeant Barrow." And he said -- I don't know where he learnt this crap, I, they, they teach it at the Army -- but I remembered him saying, "Who's president of the United States?" So, I told him, and he said, "Who won the World Series?" And then, I'm not a sport person, and I remembered saying, "Oh, who in the Hell knows who, who won the damned World Series? Who cares?" I said, "[expletive] dammit, this is the First Sergeant," and I started cussing and going on, and then I heard another man that was with him speak up and said, "Yeah, yeah," said, "That's First Sergeant."

Clark Welch: One hundred and forty-two Americans went out. Sixty-four died as a result of that fight. And almost everyone else was wounded. We were just massacred, just massacred. And my men, my men. What, what can you do? You know, uh -- just massacred.

Nguyen Van Lam, Viet Cong: We snuck back to examine the battlefield. I thought, "Holy [expletive]. Did we kill them all?" What we saw made us shudder. Because we saw how small we were compared to them, as small as one of their thighs. I never understood why the Americans came to our country. Maybe they thought Vietnam was rich, so they came over and attacked us.

Diane Sikorski: On October 17, I went to bed, and I woke up with the most intense dream that I thought it was real. I heard my brother calling my name, and the vision that I saw, he had his arms out and when I looked at him there was a giant hole in his stomach, and it was just so, so real. And that nightmare just scared the daylights out of me.

Jane Brotman: When I got up in the morning, I knew nothing about the planned demonstration against Dow. What was on my mind that day was that the following day I was going to be having my very first six-week exam at the University in my French literature class. At some point, as I'm climbing up the hill, I hear some musical instruments. In front of the Commerce Building there were a group of students and they were chanting and they were walking around in a circle. I was absolutely not a protestor that day. I felt angry at people who were against the war and, and, and antagonistic toward people who were, um, actively protesting the war.

Mark Greenside: The decision was made to peacefully sit-in and obstruct, block the interviews, stop them from happening. Not allow Dow to recruit. So, we marched into the hallway. There were hundreds of us.

Jim Rowen: By that point, we were packed in so tightly, you couldn't, you literally couldn't move. No one thought about getting hurt. We were there in the spirit of the civil rights movement -- nonviolent protest. You submit to arrest. You're making a personal commitment and a moral statement.

David Maraniss: There was always this sense that the campus was a protected haven of free speech, apart from the rest of the city. But Chancellor Sewell was under enormous pressure and he had no idea how to diffuse the situation. He called the chief of the Madison police for help. It was the first time the Madison police had been brought onto the University campus.

Jack Cipperly: I was specifically assigned to be in the Commerce hallway to maintain communication with the students. All of a sudden there was an electric tension in the hallway. And a fellow named Billy Simons came up to me and I knew Billy from the time he was a freshman, he said, "Dean Cipperly, there is police out by the Carillon Tower". And I saw the Madison police officers out there.

Keith Hackett: We didn't know what to expect, we just knew that there was only about 30 of us and we were way outnumbered.

Maurice Zeitlin: I was in my office, working on my research when a number of students barged through the door and said, "Professor Zeitlin, Professor Zeitlin, you've got to come, the police are massing outside of the Commerce Building. It looks like they're going to go in there and they're going to start beating up students." So I dash across the street to the Commerce Building. Standing there, wearing helmets and carrying billy clubs, really prepared for war, were the police from the city of Madison. I dashed to Bascom Hall to see my senior colleague, the new Chancellor of the University of Wisconsin, a man for whom I had the deepest respect, a close friendship, William Sewell. I dashed in there and I said, "Bill, you don't know what's happening! The Poli...!" He says, "I do know what's happening and I can't do anything to stop it." I said, "But who called the police?" And he said, "I called the police." And that was a profoundly, that was a profound shock.

Keith Hackett: The University had wanted us to go in and, and clear the building, and they didn't say how. They just said, "We want them removed." And we said, "Fine."

Jane Brotman: I see this man. He had a bullhorn and he made this announcement that anyone who wanted to leave the Commerce Building should leave now because in two minutes the police were going to be entering the building and they were going to be arresting anyone who was there. But the thing that happened was that not, I don't think even 10 or 20 seconds elapsed when all of a sudden the, the police stormed the building and I remember they had these billy clubs and they were breaking the glass doors of the Commerce Building.

Keith Hackett: When the window went out, everything, everything turned loose. They turned loose, we turned loose and it was a matter of who's going to win.

Jim Rowen: A new sound emerged out of the commotion. It sounded like somebody breaking watermelons with a baseball bat. That was pretty frightening because we were trapped and this sound was approaching.

Paul Soglin: Just in an instant they came at me and grabbed me. They just proceeded to alternatively club me, and somebody just whacked me on the base of the spine.

Keith Hackett: You either grab somebody, you hit somebody, you knock them down, and you step over them. The line behind you picks that guy up, throws him back to the line behind, who takes him and throws him out the doors that we just came in. Literally, we had stacked up bodies like cordwood between the doors.

Jane Brotman: People were trying to get out and, as the people were trying to get out, they were beating people up with billy clubs. You know, eh, as hard as they could. You could hear the whack. Sixty-five people were sent to the hospital. It was the most brutal and violent thing I had ever witnessed in my life up until then and continues to be the most brutal and violent thing I have ever witnessed in my life.

Paul Soglin: These officers were pissed. There's no question that they wanted to inflict some damage. They were speaking through those, those clubs.

Jim Rowen: The authorities seemed not to be interested in arresting people as much as they were interested in attacking the demonstrators.

Keith Hackett: And it wasn't revenge on anything. If you got a student, you tried to make sure that he didn't return, that he didn't want to come back. And if that meant, you know, breaking his kneecap, that's what you did.

Maurice Zeitlin: Police were yelling and they were smashing the kids. It was horrendous, you know, and I'm standing outside of the building and, and I was naive enough to say to them, "I'm a member of the faculty, my name is Professor Maurice Zeitlin" and while I'm giving this silly speech to the police, a police officer swung at me, students jumped on the police officer, there was a melee, I was on the bottom of this. And I could actually hear the thud of club on body.

Jack Cipperly: I saw a policeman raise his club and I thought he was about to hit a student and I couldn't help myself, I just grabbed him, he had a face mask on, and it wasn't until I was inches away from his face, I realized he was a person that I had gone to high school with, and I said, "Jerry, what are you doing?" And he said to me, the same thing, "Jack, what are you doing?"

Jane Brotman: All of a sudden there were about 4,000 people watching this scene because people were either coming to class or leaving class. I remember people starting to scream, "Sieg Heil! Sieg Heil!"

Maurice Zeitlin: In fact, that event, the police smashing students, politicized students who didn't even know the war was going on. But when they saw, on their own campus, their fellow students being smashed by police, it was natural for them to turn out. It was in their nature.

Keith Hackett: I mean, the crowd just seemed to swell. Bricks were coming, rocks were coming, spit, anything you could think of. I had never seen the hate that I saw in these kids' faces, you know, towards us.

Tom McCarthy: A half a brick came flying over and hit me flush in the face and knocked me cold, knocked me out.

Keith Hackett: Everything was out of control. And somebody -- and I'm not sure who -- ordered up tear gas.

Jane Brotman: And all of a sudden, my eyes started stinging and there was this odor, this, this funny smell.

Jim Rowen: And it went into classrooms, and, you know, there were professors stumbling out of buildings, who had been tear gassed. My head was just spinning. I thought everything had changed, everything was different now.

Tom Hinger: On a normal rifle company, if it took twenty helicopters to move us in and out of a night defensive position, and this day there were five helicopters. And this sergeant was standing there, this grizzled sergeant, and the tears were just running down his face and he said, "My God, sir, is that all that's left?"

Jim Shelton: The next call I got was Major Shelton, go down and identify bodies. So I went down and I saw all my buddies. I just felt like how could anything be worth this?

Mike Troyer: In some of these body bags there was just parts. And this one body bag, I told this mortician, whatever he was, I said, "If that arm, with that 101st Airborne tattoo, belongs to the rest of those parts in that bag, I know who it is," and I identified that as Schroeder.

Jim Shelton: I was kind of wandering around in a daze, and I heard trucks, and on these trucks there was American soldiers in brand new uniforms, and I just stood there looking at them. That's the new battalion, new meat. These guys were all replacements for all our guys.

Clark Welch: I remember waking up on a table. I'd been shot in the left arm. I'd been shot in the chest. I'd been shot in the right arm and I'd been shot in the right leg. Everything had been shot except for my left leg. A beautiful woman was leaning over me and saying, "Lieutenant Welch, it's going to be all right. You're going to be all right." And then she stepped forward, and I grabbed her, and what I said to her is, "My Delta, my Delta, what has happened to my Delta? Where is my Delta?" And she said, "Delta's gone." And then that's all I remember.

Bert Quint, archival footage: In the search and destroy operations that characterize the war in this part of Vietnam, it's usually a case of "search and not find". This time, practically by accident, the Americans and the Viet Cong did find each other.

Tom Hinger: We were ordered to make ourselves available in front of the Alpha Company area. They had set some chairs up.

Mike Arias: And we were debriefed before we went into the hooch to interview with CBS news, that we were not to mention that it was an ambush. From my perspective, I was pissed because it was an ambush. I felt at that time and I still do now, that there was a cover up.

General Westmoreland, archival footage: We have a pretty good idea of the enemy troops in this area. We have quite a bit of intelligence on this particular regiment.

Reporter, archival footage: What happens now, sir?

General Hay, archival footage: What happens now? What happens now is we continue to work on them until we destroy them. This is what I had hoped we could do for a long time is get them to stay in one place.

Jim Shelton: I understand why General Hay didn't want to use the word "ambush", because an ambush means you're incompetent. The problem was what was said about it was a spin, which made it sound like this battle was part of something bigger which was very successful.

News Anchor, archival footage: In Vietnam, the first infantry division in a costly bitter battle with the Viet Cong in the Iron triangle forty miles northwest of Saigon, has reportedly smashed a guerilla plan to overrun Saigon itself. The battle took place yesterday between fifteen hundred Americans and twenty-five hundred Viet Cong. Before the fighting ended, 58 Americans were dead including Lieutenant Colonel Terry Allen Jr., son of the World War II general who commanded the first division in Europe.

Jim Shelton: It was a total fabrication of what really happened. It kind of, like it showed, like a victory. "The Americans held them off, bah, bah, bah, bah, 103 enemy killed" and all this stuff, and that haunted me. I'm not a cynic, but I started to become one, you know, of history, you know. What the hell, who the hell knows what really happened if that's the way history is written?

Politician, Archival Footage: Reports will indicate that a squad of fifty Madison policemen were called to the scene and were met by an angry, vicious mob of 300 or more protesters led by, in many cases, professionals from out of the city. And that virtually individual officer's reports would indicate that at times they were fighting for their own lives.

Mark Greenside: In the days after Dow, the newspapers came out with stories that essentially blamed the students for what happened and blamed us for provoking it and causing it, and for attacking the police and, you know, making them have to defend themselves against us. And, eh, it just added to the credibility gap that we already felt with all of the institutions of authority.

Reporter, archival footage: Is this going to be a recurring thing, do you think? Do you see any end to this type of thing, here?

William Sewell, archival footage: I certainly hope that it's not a recurring thing. However, when we are warned in advance that people are going to disrupt, we have to try to prevent that disruption.

Jim Rowen: It just blew my mind. It just shocked me, that the University, as I saw it, had chosen, had taken sides. You know, they were with Dow; they were with war profiteers; they were with weapons makers. You know, they were really part of the war.

Maurice Zeitlin: That was the beginning of a movement on campus. Until then, there had been antiwar demonstrations on campus; there had been antiwar teach-ins on campus; but that gave rise to a spontaneous outpouring. Students said, if they're doing that to us here, if they're doing that to us here for peaceful protest for doing nothing more than sitting in, maybe the United States is the bully abroad as well.

Jack Cipperly: There were students that I knew very well as thoughtful people and I began to think, well, if they felt strongly enough to put their bodies on the line, perhaps I ought to question a little more deeply some of these things.

Mark Greenside: A strike was called. Classes were canceled. Probably a third to forty percent of the University was stopped on that day.

Jane Brotman: I thought, you know, "I have to strike." But then the realization hit me that if I were to participate in this, I would have to miss, not show for my first six week exam as a freshman at the University. I really had to go inside and decide that I had a civic responsibility to say that what I had witnessed was wrong. There was a real process of transformation in terms of my thinking. I now felt like I was part of this anti-War movement on campus, which had grown into a real, sizeable movement after Dow Chemical.

Joe Costello, read from letter: October 22nd. Dear Arlene, Hello, baby. How's my girl? I'm much better. The doctor sewed up my wound this morning. This afternoon at about five p.m., General Westmoreland came and presented me with the Purple Heart and congratulated me for the Silver Star. They had television cameras and lights, too. I wonder if anybody saw me at home.

Joe Costello: One of his aides I remember came to me and he said "Look Costello, we know you're 18 years old. The general's going to come and give you the Silver Star and he's probably going to ask you how old you are and, when he does, I'd like you to say you're 19 or 20."

Bud Barrow: General Westmoreland came into the ward, and shook hands and said, "Congratulations." I said, "Are you congratulating me or the enemy?" And I said, "We lost that battle."

Clark Welch: I remember vaguely waking up enough to know that there's General Westmoreland and somebody being there and somebody taking some pictures and somebody shaking hands, and then I believe General Westmoreland, fine old man, leaning down and saying, "Well, son, I'm glad, eh, I'm glad you're all right. Tell me what happened that day."

Bud Barrow: And I said, "Sir," I said, "We got ambushed." "Oh, no, no, no," he said, "No," he said, "That wasn't no ambush." And I said, "Well, General, then I don't what happened to the other people out there, but, by God, I was ambushed."

Clark Welch: And I recall then that I said, "Sir, I will tell you what happened today. The [expletive] damned Army is [expletive] up from the President of the United States on down to my boss the Colonel, and I'm glad he's dead." A deep anger still lasts towards the army, the organization, the government, the President of the United States. Just look what you've done. Look what we've done.

Diane Sikorski: On October 20, I remember being in my bedroom and the doorbell rang, and I peeked out and I saw a soldier in uniform. My heart just fell to my feet because I just knew why he was there. My head went blank and I remember just being so cold and shaking and just holding my arms real tight. I didn't want to hear it. And I do remember him saying, "Killed in Action." And my dad was yelling from deep in his heart "Oh, God, no! Not Danny! Why couldn't God take me instead?" I remembered the dream that I had of Danny and everything just clicked -- I knew he was dead. I believe that that was, that was Danny's last goodbye to me -- in his own way, that he reached out. And that was our final hug.

Jean Ponder Allen: Two officers came to the house. They told me that Terry had been reported missing in action. I started screaming at the officers and I told them that they were lying to me and that I knew that he was dead. It was just loss, loss of so much. Not the passing of someone that we could say died in a way that clearly was going to bring about some greater good. It was just loss.

Robert Cohen, archival footage: They may expel thirteen of us, and I wonder what they're going to say, you know, about the new little "clique," the new outside agitators who run this movement. Because that's not what the reality is. The reality is that there is a very real social movement in this country.

Lieutenant Governor Olson, archival footage: Starting on Monday morning at ten o'clock, we're going to call in witnesses and they will be asked to testify and if they don't testify freely we will be subpoenaing them. We can assure anyone it's not going to be a witch hunt.

Maurice Zeitlin: The administration at the University of Wisconsin wanted to punish the students, not just for sitting in, but to punish the students precisely because they were taking positions which they vehemently opposed. And Bill Sewell got trapped. To me it was a very profound lesson, how men who oppose the policies of their government nevertheless find themselves upholding those policies in practice, by virtue of the position and the pressures put upon them.

David Maraniss: I came to interview Bill Sewell 35 years after the event, and the pain was still there. Ninety years old at that point. When he started to describe what happened in those few minutes, seeing the police go in with their billy clubs and seeing kids come flying out with their bloodied heads, he started crying.

Tom McCarthy: I went to mass that Sunday, and the priest was giving his homily, and he said something about, well maybe, you know, the students have something to say, and we should start listening to them. Got up and walked out. I remember the priest very well. I don't think I ever spoke to him again. I didn't think they, you know, you go to school, you got nothing to say.

Keith Hackett: After October 18, rioting in Madison became a routine thing. We were going through fifty-thousand dollars of gas a week. We had sometimes lit up the streets to the point that it looked like a fog. We said, "Hey, they're trying to take over my country, and I'm not going to permit that to happen."

Mark Greenside: The Dow demonstration is the first violent anti-War demonstration to take place on a University campus. Now, in the next 3, 4, 5 months, once you hit '68, everything is gonna pop. But I think Wisconsin is the first, and Dow was the bell.

David Maraniss: The antiwar movement, from that point on, just grew larger. A few days after Dow there was a protest in Washington, really the first massive antiwar protest at the Capitol. When the Tet Offensive comes three months later, public perceptions changed forever from that point. That was the point where the American public essentially concluded that Vietnam was not worth fighting and unwinnable. From the time these Black Lions were killed that day, from the time of that protest at Wisconsin, the people responsible for the war essentially knew that they couldn't win it. Well, it went on another eight years, and that's another part of the tragedy.

Joe Costello: When we flew home, I was with two guys that I knew. We took a taxi-cab to the San Francisco airport, and the taxi-cab driver talked about the price of tires and the traffic and never quite got around to saying, "Hey, welcome home," or, "How was it?" or, "Good luck," and I thought that this is probably a sign of things to come.

Mike Troyer: I mean, I knew my parents would be happy to see me. I didn't know if anybody else would be happy to see me, so I knew I was going to have one good friend -- me -- and so, I sent a letter home to myself. And I actually opened that letter when I got home. I mean there wasn't no brass band waiting on you, nothing. You weren't a hero. You lost the war.

Bud Barrow: I was pretty bitter. I considered those people to be traitors, I mean, traitors, cowards and any other dirty name you could come up with. As far as I'm concerned, they can line those people up and shoot them right between the eyes. That's a pretty hard stand but that's the way I feel about it.

Nguyen Van Lam: My mother and father were both lost to the war. So now there's only me, nobody else. My wife's family is also completely gone, only her left. All lost to the war. My house is on the battlefield where we fought that day. My neighbors ask if I'm not afraid with the ghosts of all the dead Americans tugging at my feet.

Clark Welch: You know, nobody gives up their life for their country. They have their life torn away from them. Nobody, nobody gives up their life for their country. None of my guys signed up for that.

Ernie Buentiempo: I see their faces, and that's what hurts so much, you know. They're so young, to die so young for a needless cause. That's a high price to pay for something that's wrong. And as you look at it now, you know it was wrong. We had no business being there.

Jim Shelton: I'm not ready to give up on Vietnam as a force for good, okay? I'm not ready to admit that was an evil thing that happened to the United States of America, that never should have happened, or even that it wasn't worth it. Now, part of that is because I can't accept the deaths of my buddies as not being worth something.

Jean Ponder Allen: I've had many years to reflect upon my decisions and my actions and realized where I acted stupidly and in haste, foolishly, and cruelly. But I have never changed my mind about the wrongness of the war in Vietnam.

Jane Brotman: You need to have people who are willing to stand up and take action when they think something is wrong. I mean, that's what a democracy is all about.

Mark Greenside: It changes who you are, when you put that kind of time and that kind of effort into a cause. You emerge from that different. And I think we emerged from that absolutely less optimistic, absolutely less hopeful. We were committed and willing and wanting to give everything. They didn't want it and we stopped giving it, and the fact that it's not around now in the way it was then I think is extremely harmful to the country. I think every country needs the kind of idealism that we had.

Maurice Zeitlin: I have only respect for the men who fought in that war, because they didn't make the war, they didn't choose to fight in that war, but they accepted a responsibility that they thought was theirs as an American citizen, okay? They carried the burden of being an American citizen. When they were sent to war, they fought. And I carried the burden, not at all comparable, of being an American citizen by opposing that war. And I had the choice and they didn't. And, for that, I was privileged and they weren't, but we were both doing our duty.

Diane Sikorski: I think back then if people tried in any way to stop the war they probably felt that they were doing the right thing. On the other hand, the boys of Vietnam felt they were doing the right thing. In the end I wonder who was right.