Floyd Norman: Every time Walt walked down a hallway, he would give a loud cough. It was a warning sign so we would know that the boss was in the area.

Richard Sherman, Songwriter: In Bambi, there's a line when "Man is in the forest," there was danger. You have to be worried. We'd hear Walt coughing coming down the hall, and one of the guys would say, "Man is in the forest." And we'd all get ready for Walt.

Rolly Crump, Imagineer: He walked through the door and, you know, pins would drop. You couldn't hear anything. His personal power walked right with him.

Richard Sherman, Songwriter: There was no joking around. He would sit down, he'd say, "Okay, guys, what you got?" And I would say, "I got a great idea," and Walt would say, "We'll tell you if you have a great idea. You have an idea."

Narrator: Walt Disney was an international celebrity by the time he was 30, hailed a genius before he was 40, with honorary degrees from Harvard and Yale. He built a media and entertainment company that stands as one of the most powerful on the planet...

Walt Disney (archival): This little fellow is Bashful.

Narrator: …won more Academy Awards than anybody in history, created a cinematic art form, and invented a new kind of American vacation destination. Disney's work counts adoring fans on every continent and critics who decried its smooth façade of sentimentality and stubborn optimism, its feel-good re-write of American history.

Ron Suskind, Writer: Disney's a Rorschach in America. The love and hate, it's off the charts. But, God, you have got to respect the energy of this guy. I mean, he is lunging every day of his life.

Walt Disney (archival): "Well, kids, Babes in Toyland is finished, and now it's time to celebrate!"

Richard Schickel, Writer: Nobody who does stuff on the scale that he did is a sweetheart of a guy. I think he wanted to be what his image was. He wanted to be thought of as a hail-fellow-well-met, good-natured. But he wasn't.

Neal Gabler, Biographer: Walt Disney is in many ways a very dark soul. And one could say that he fought that, fought that darkness, tried to find the light.

Sarah Nilsen, Film Historian: He is feeling so much inside and he wants people to feel what he feels is inside. He could take those feelings that were so central to who he was, put 'em on screen, and allow other people to also feel them along with him.

Neal Gabler, Biographer: Most successful people, they get one thing right -- and that's it. But Walt Disney was a guy who got a whole lot of things right. What did this guy understand about the human psyche?

Richard Schickel, Writer: Walt Disney was as driven a man as I've ever met in my life. What he really wanted to do was, as we used to say in the Middle West, make a name for himself. He had a sort of undifferentiated ambition. He wanted to be somebody, that's for sure.

Narrator: Walt Disney was still a few months shy of his 18th birthday when he returned from France after the first world war in 1919, and he was already better off than most of the two million other American boys streaming back home. 'Diz,' as his friends called him, had banked over $500, and had a place waiting for him at a Chicago jelly factory where his father was part-owner. The job offer was the best most working-class boys could hope for, but Walt Disney was not like most working-class boys.

Don Hahn, Animator: He's got all these ideas, and he starts acting on them. And where most people were "ready, aim, fire," he was like, "ready, fire, aim." You know, he was like, "Let's go!"

Neal Gabler, Biographer: Walt loved attention. He was an extrovert. He loved to be the center of attention. He wants to be an artist. And I think he discovered something early on: That talent was his way of getting attention. He's a man of the times. And the times are exciting.

Narrator: Walt was determined to do work he loved, and he had been an enthusiastic artist and cartoonist from the time he was little. He took a pass on factory work in Chicago and headed for Kansas City instead, where he had spent much of his boyhood. He moved into a house with two of his older brothers, and landed a job as a commercial artist for a local ad company.

Soon he was making enough money for fashionable clothes, fine cigars, meals at nice restaurants, and near-nightly trips to the movie houses springing up all over town. Disney's evenings in these new palaces of celluloid fantasy included at least one feature film, maybe a serial short, a newsreel, and an animated cartoon or two.

Tom Sito, Animator: It was an exciting and very dynamic medium. The industry was very young. There was no regulations, or no customs, or no conformity. It was wide open to what people wanted to make of it.

Narrator: Disney was captivated. His only formal training was a few months at an art school in Chicago, and a course at the Kansas City Art Institute, but he was convinced he could make better than what he was seeing.

He checked out from the public library Eadweard Muybridge's Human Figures in Motion. Then he borrowed a volume that laid out the basics of animation in filmmaking. Disney read about roughing out a storyline, creating characters, and carefully drawing each individual frame onto white linen paper; by mounting each frame on pegs, just as the book instructed, and shooting them one at a time, he began to create the illusion of movement.

Sarah Nilsen, Film Historian: He was really into modern culture. The pleasure of somehow engaging with the potential of cinema, the potential of animation was exciting to him. And he had this little ability to draw. He had a knack.

Narrator: Disney's first efforts were short cartoons he made on nights and weekends with a film camera he borrowed from his boss at the ad company. "I gagged 'em up to beat hell," he would say, and then sold them to a small Kansas City based theater chain. The fees didn't even cover his costs, but Disney gained something more important than money: attention, excitement... a whiff of destiny. "My first bit of fame came there," he said. "I got to be a little celebrity."

At age 20, Disney quit his day job, and started a company -- Laugh-O-grams, Inc., Walter Elias Disney, president. He hired a salesman, a business manager, and four young apprentice animators.

Don Hahn, Animator: I can imagine a young Walt Disney just, you know, waking up at dawn and going out with his friends and saying, "Well, let's shoot this. Let's film this." And that kind of hunger for not just expressing himself but finding out who he was. He couldn't do enough.

Steven Watts, Historian: He has stars in his eyes. He thinks he can do anything and everything that he wants. He has big plans. He's going to conquer the world.

Narrator: Just as he was beginning to get some traction in the modern movie industry, Walt's parents arrived from Chicago. Elias and Flora Disney moved in with their sons because they had nowhere else to turn; the jelly factory had failed -- the latest in a long line of Elias's business disasters.

While Disney's mother tried to be supportive of Walt's new career, his father took little joy in his youngest son's minor celebrity. He told Walt not to expect his new success to last. Walt began to worry he was going to end up, once again, in service to his father.

Ron Suskind, Writer: Disney lived a very, very difficult existence in Missouri as a kid. He works all the time. His father is an imperious, withholding, kind of brutal character. "You're here to work, and work to help me." That's Dad.

Neal Gabler, Biographer: It's hard to find a father and son who are more different than Elias Disney and Walt Disney. Walt Disney was fun-loving. He loved practical jokes. He was a kid who just loved people. Walt was antithetical to Elias not only by temperament, but also by will. He determined, "I'm going to be everything he isn't. I'm going to be the antithesis of him. Look at his life. I don't want to live that life."

Ron Suskind, Writer: He survives a life of deprivation, of have not, of no time to do the things that kids should do -- play, enjoy, laugh. And the minute he gets into full upright adulthood, whether he says it to himself or not, he's like, "I am going to make amends for that in some way. I don't know how, but I yearn for the things that I didn't get as a child."

Narrator: Disney and his Laugh-O-grams crew secured a contract for six animated fairytale shorts, but when they delivered the work, the distributor stiffed them. Walt could no longer make payroll, or pay the rent on his office, the phone bill, the electrical bill. Creditors began circling, while Walt insisted he had discovered the means for a daring escape, which he explained in a Hail Mary letter to one of the best-known cartoon distributors in New York. "We have just discovered something new and clever in animated cartoons," Disney wrote. His big idea was to insert footage of a real girl into animated scenes. Alice in Cartoonland, he crowed, was "bound to be a winner."

"He was always optimistic about his ability and about the value of his ideas," Disney's business manager recalled. "He believed in himself, and he believed in what he was trying to accomplish."

Walt was able to scrape together just enough cash to complete Alice. He finished his cartoon experiment with little help while sleeping at the office, bathing at the train station, subsisting on canned beans and the charity of a Greek diner. But, by the time the cartoon short was finished in the summer of 1923, it was too late. His company was headed for bankruptcy court. Alice in Cartoonland would not save Laugh-O-grams, Inc. Walt Disney had suffered his first real failure.

He packed his cardboard suitcase with two spare shirts and what was left of his drawing supplies, then headed for Union Station, where he treated himself to a first-class ticket on the Santa Fe California Limited -- straight through to Los Angeles.

Steven Watts, Historian: Hollywood in the 1920s is a beacon of the future. It's this golden city on the west coast. Hollywood, Los Angeles -- that's where the action is at. And I think Disney senses that, and that's where he wants to be.

Neal Gabler, Biographer: He's not thinking about animation now. He's already failed with animation. So the next step is, "I'm going to go out here and I'm going to become a movie director. That's what I'm going to do."

Narrator: The want-to-be movie man walked past Charlie Chaplin's studio along La Brea Avenue, rode the trolley to Culver City to see the set used in Ben-Hur, and talked his way onto the Universal lot -- where he wandered around late into the night. But after weeks of effort, Walt had not been able to talk his way into a job.

His older brother Roy, who had moved to Los Angeles for health reasons, had little patience for Walt's insistence on finding a place in the movie business. Roy hadn't been star-struck on arrival. He sold vacuum cleaners door-to-door when he first got to town, and he admonished his brother to find a similar job -- one that paid. Walt was considering this advice when a cartoon distributor from New York got in touch. Margaret Winkler, the only woman in the business, had remembered Walt's Alice in Cartoonland pitch, and wanted to see how the young animator's big idea had turned out. Soon after Disney shipped his Alice reel to Winkler's office in New York, the distributor wired back an offer. She wanted Walt to make 12 Alice shorts, and was willing to pay $1,500 per episode.

Neal Gabler, Biographer: When he gets that telegram, the first thing he does is, he goes to visit his brother Roy. And Walt is waving this telegram, saying, "Look! We've got a chance here!" His brother is not enthusiastic. His brother has no entertainment ambitions whatsoever. His brother is the pragmatist. But Walt says, you know, "We can do this. I need you for this." Roy, as much as he was a naysayer, he loved the enthusiasm of Walt, and I think he thrived on it. He got joy from participating in the kind of wild schemes of his brother that he himself would never have concocted. Roy got release, and Walt got protection.

Narrator: The two brothers scraped up a little cash from friends and relatives and set up a two-man operation in the back of a real estate office. Walt was the artist and idea man; Roy was the fundraiser, the bookkeeper, and the all-around utility man.

But Walt recognized that he needed the kind of help Roy could not provide. So he convinced an old friend and collaborator, Ub Iwerks, to relocate from Kansas City to Los Angeles.

Don Hahn, Animator: Walt loves to draw, and he can draw, and he gets attention by drawing. But -- how do I put this discreetly? Walt Disney wasn't the best artist in the world. He grew up in an era of an age of illustrators that was surrounded by great art. Um, he wasn't that. And I think he saw that pretty early on.

Eric Smoodin, Film Historian: Iwerks is incredible and can work fast. So it's an early sign that Disney always wants to work with the very best and isn't afraid of working with someone who's better than he is at many things.

Narrator: Iwerks began re-styling the Alice's Wonderland shorts as soon as he arrived, creating films with less emphasis on the girl and more on the cartoon characters. The Disneys' distributor loved the new look. They wanted more, and faster, and were willing to pay good money to get them. Walt recruited more of his old gang from Missouri, then hired some locals, and the number of employees at the Disney studio swelled to a dozen.

Steven Watts, Historian: The difference between Laugh-O-grams and Disney Brothers is Roy. Roy was in the latter and he was not in the former. And from the very beginning, I think Roy helped put financial and business structure in place that grounded the enterprise.

Narrator: The brothers enjoyed their early success, and expected it to continue. Roy bought a stolid new sedan; Walt a snazzy Moon Roadster. They purchased adjoining lots and built new houses next door to each other.

In the spring of 1925, Roy married Edna Francis, his longtime sweetheart from Kansas City. Walt, sporting a rakish pencil moustache, acted as best man while escorting his girlfriend Lillian Bounds. The couple had met in the office, when Lillian was working as an inker at the Disney Brothers Studio. "He just had no inhibitions," Lillian said of Walt. "He was completely natural. He was fun." Three months after Roy and Edna's wedding, Walt and Lillian tied the knot.

The Disney Brothers Studio was churning out a new Alice short every 16 days at the beginning of 1926, and Walt and Roy were ready to hang their shingle on a more spacious building in the Silver Lake neighborhood of Los Angeles.

Steven Watts, Historian: When they moved from the Disney Brothers Studio to the Hyperion Avenue facility, a very striking and a very revealing thing happens. Walt goes to Roy and he says, "I've made a decision, and that decision is, from hence this will be called the Walt Disney Studio, not the Disney Brothers Studio." Walt Disney believed that it was his vision of creativity and entertainment that was the engine of this enterprise, and that's what was being sold.

Narrator: Disney was understandably obsessed with his rivals in the cartoon industry by the end of 1926. He could tell his Alice pictures were running out of steam and spent much of his free time in darkened theaters, assessing the work of the top New York-based animators: the Fleischer Brothers and Pat Sullivan. He was taking aim at the industry's gold standard, Sullivan's Felix the Cat.

Sarah Nilsen, Film Historian: If you look at animation at that period it's extremely crude, it's really violent, it's really gag driven, and it's very urban. These are older men making kind of crude, hard animation. And Disney steps in as this young guy and he's like, "Okay, well, I see what you're doing, I'll try this out and then I'll figure out my own voice in my other influences around me to transform it."

Narrator: The key to challenging the supremacy of Felix the Cat, Walt believed, was creating his own compelling and likeable character. Disney's distributor suggested he try a rabbit -- "too many cats on the market." Iwerks took charge of Oswald the Lucky Rabbit's look, while Disney wrote the storylines and the gags. The bosses at Universal Pictures were so taken with the first sketches of Oswald they offered a contract for 26 episodes.

Walt Disney Studios seemed to be riding high, but by the time the team put the finishing touches on the first order of Oswald shorts, the animators were increasingly frustrated with the boss. The old Kansas City hands who had helped Disney get started in the business, and often without pay, were working into the night and through the weekends, while Walt was taking much of the money and most of the credit.

Steven Watts, Historian: I think the two sides of Disney emerge. You have on the one hand Walt the Inspirer. The other side of Disney was Disney the Driver, who demanded work, who demanded creativity, demanded productivity. And if people didn't meet his standards, he could come down on you like a ton of bricks.

Narrator: Charles Mintz, Margaret Winkler's new husband and business partner, saw an opportunity -- emboldened by the knowledge that he owned the rights to Oswald, and the Disney brothers did not.

Neal Gabler, Biographer: Ub Iwerks comes to Walt Disney and says, "Walt, I've been approached by Charles Mintz to essentially leave you and to go to work for Mintz. And I'm not the only one. All of the animators have. But they haven't told you."

Steven Watts, Historian: Disney doesn't believe it. He just sort of pooh-poohs the whole thing and doesn't really believe Ub Iwerks, who says, "No, there's a problem brewing here."

Narrator: Walt went to New York in February of 1928 with big hopes for a new contract from Mintz. But it only took a few days for Disney to realize that Iwerks had been right -- Mintz had already poached almost all of Disney's artists except for Ub, and the distributor told Walt he was going to go on making the Oswald Cartoons without him.

Sarah Nilsen, Film Historian: Things are unfolding that most people would understand and Disney comes into it shockingly naive. It was pretty clear that people were unhappy around him, that he was pretty oblivious to that. He's very driven by his vision, and, when these kind of business failings occur, he is completely caught off guard.

Narrator: When Disney boarded the train for the trip back to Los Angeles, he was despondent. Almost all of his team had abandoned him. He had no distributor, no Oswald, and very little money in the bank.

Don Hahn, Animator: Oswald the Rabbit gets taken away from him like a kid taking your lunch money. They were looking the other direction and Oswald was gone.

Narrator: It was a long cross-country ride for Disney. The train made stops at most of the big cities along the way and blew through countless other small towns on the line. One of them was Marceline, Missouri. Disney had first seen Marceline at the age of four, when his father had fled the big city of Chicago and moved him, his mother, his three older brothers, and his baby sister to a little farmstead there. It was a place Disney never forgot.

Steven Watts, Historian: Walt was living in the country, on the edge of this town, and he was surrounded by nature. He could romp through the woods and run through the fields. There were farm animals around, and he loved animals -- had a pet dog, pigs, cows, horses.

Sarah Nilsen, Film Historian: Marceline represents really the one moment in his childhood where he was a child, the place where he really was allowed to be free, where he wasn't being told what to do by his dad.

Ron Suskind, Writer: Marceline was this seemingly idyllic place hitting Disney at a certain age. You know, the rhythm and the beat of the place is just right for a kid. It's like the last breath of something that seems to resemble a traditional childhood.

Narrator: The Disney family business was a tough go: the margins were always slim, and Elias wasn't much of a farmer. Just five years after they arrived, Disney's father announced that the family was pulling up stakes and heading back to the city.

Walt Disney (archival audio): My dad sold the farm, but then he had to auction all the stock and things. And it was in the cold of the winter, and I remember Roy and myself going out and going all around to the different little towns and places, tacking up these posters of the auction.

Neal Gabler, Biographer: Walt Disney once said that he'll never forget his days in Marceline and almost everything important that happened to him happened in Marceline. But I think that has to include also the losing of Marceline.

Narrator: When Walt and Lillian arrived at Union Station in Los Angeles in mid-March 1928, Ub Iwerks detected none of his friend's trademark good cheer and enthusiasm. He looked like he'd just run into a "stone wall," Ub would say.

Neal Gabler, Biographer: Coming from the Disney family, where his father had suffered so many successive failures, I think you can only imagine the impact that had on Walt Disney. Failure was a big thing in the Disney family.

Sarah Nilsen, Film Historian: Where his dad just continually gets more and more depressed, quits basically, Walt steps up. Boom. You think Oswald was good? I can do much better than that. I'll show you what I'm capable of doing.

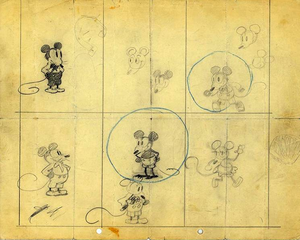

Narrator: Disney held daily brainstorming sessions with Roy and Ub and a few other loyalists who had not signed with Mintz. Intent on dreaming up a bankable new character -- and one they would own -- Disney's skeleton team scoured popular magazines for inspiration, bounced ideas off one another, and drew figures on their sketchpads... until something began to emerge.

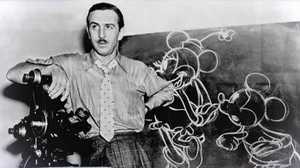

"Pear-shaped body, ball on top, a couple of thin legs," Iwerks later explained. "You gave it long ears, and it was a rabbit. Short ears, it was a cat. With an elongated nose, it became a mouse." Walt suggested they name him Mortimer. Lillian thought that was terrible and came up with Mickey. As with Oswald, Ub took charge of the mouse's look. Walt gave him his personality.

Carmenita Higginbotham, Art Historian: He doesn't have the financial backing to support what it is he's doing. He wants to be a bigger voice than he is. And it's a perfect metaphor him being this small mouse, this seemingly insignificant figure or individual within this big industry that he wants to break into.

Narrator: Disney was unable to find a distributor willing to take a chance on his first two Mickey shorts, but Walt refused to give up on his mouse. At a meeting with Roy one day, as the tiny staff worked up a third -- and still unsold -- Mickey Mouse cartoon, Walt suddenly blurted out, "We'll make them over with sound!"

Sarah Nilsen, Film Historian: "How can I do something better with animation than what everybody else is doing?" He's always the person looking for new technology. He's always the person trying to find the newest invention to make animation better.

Eric Smoodin, Film Historian: At the time, producing a soundtrack in synch with and music that makes sense with the action on screen is very difficult. This was a very precise and intricate process that Disney had to think through. And also it's unclear that the money it costs to make a sound film can possibly pay off with tickets sold.

Narrator: Disney saw no good option but to take the chance. He headed back to New York and signed a quick deal with the licensor of one of the most advanced sound systems in town. Walt didn't have enough money in the bank to pay for the recording sessions, so he wired Roy to do whatever he had to, to get the cash. He told his brother to sell his beloved Moon Roadster if needed.

Stuck in New York to oversee the sound work, Walt trolled desperately for a distributor. He carried his reels from one office to another for three long months -- and came up empty. He did manage to secure a two-week run at the Colony Theater -- Broadway and 53rd. Steamboat Willie premiered on November 18, 1928.

Mickey Mouse, Steamboat Willie (archival): [whistling along to music]

Narrator: The crowd at the Colony Theater was in thrall. People heard sound in pictures before, but never like this. The music and sound effects were part of the gags. "It knocked me out of my seat," one New York reporter wrote. A few audiences begged the projectionist to delay the start of the feature and re-run Steamboat Willie.

Tom Sito, Writer: Steamboat Willie was such a huge hit, and it gave Disney Studio a really sort of a preeminence, where suddenly this company is now like taking a step to the front ranks. This upstart from the West Coast just erupts in the middle of everybody with this amazing character.

Mickey Mouse (archival): [singing]

Narrator: Mickey was a multi-talented charmer -- a dancer, a comedian, a singer, and within months, never mind he was just a cartoon, Mickey Mouse was the newest Hollywood celebrity.

Mickey Mouse (archival): [finishes singing]

Narrator: While the country slid toward economic disaster in 1930, the fame of the Disney mouse just kept growing, as did Mickey's standing as the archetype of the American can-do spirit.

Carmenita Higginbotham, Art Historian: Mickey Mouse is scrappy. Mickey Mouse is a survivor. Mickey Mouse is somebody during the years of the Depression who takes a limited number of skills and a limited number of resources and he always ends up on top.

Ron Suskind, Writer: Mickey's a little bit in your face.

Mickey Mouse (archival): Howdy-do!

Ron Suskind, Writer: Mickey's like, "Hey. I'm smart. I can do anything. I get into trouble but I get out of it. I'm sort of rebellious." You know, "I live by my own rules." He's an adolescent dream is what he is -- rebelling and making it work. That's Mickey.

Steven Watts, Historian: Walt Disney was certainly not a social theorist. He certainly didn't think through the problems of the Depression. But what Disney did do was to have a kind of instinctive, impulsive feel for the problems and the hopes of ordinary people.

Sarah Nilsen, Film Historian: There's always mishap. There's always sort of the slapstick-y bit that interferes with his success, and then he triumphs and he wins at the end. And he usually gets the girl, too.

Mickey Mouse (archival): Let's all sing the chorus, again! Ooh the old…

Narrator: Mickey Mouse Clubs began sprouting up at local movie theaters. More than a million children signed up. Roy encouraged the clubs, and saw in Mickey's growing popularity another possible stream of revenue -- licensing. The Disneys had made a few haphazard deals to allow Mickey's likeness on children's toys following the example of other popular characters like Felix the Cat. But the Walt Disney Studio got less than five percent of the take, and saw little revenue -- until they brought in Kay Kamen.

Steven Watts, Historian: He was an ad man. He was a marketer. He had a very keen sense what we would call branding. Kamen is a genius for doing these licensing agreements with companies all over the United States who want to associate their products with the success of the Disney studio.

Narrator: The Disney brothers gave Kamen the exclusive rights to license Mickey Mouse -- along with his girlfriend Minnie, his dog Pluto, and later Donald Duck. The studio kept a tight rein on how their productions, especially their mouse, could be used, and they demanded a big cut of the profits, but they had plenty of willing partners because Mickey Mouse moved product.

By the early 1930s, fans could buy Mickey-adorned merchandise by the scores. The Mickey Mouse watch became the most popular timepiece in America. Fan mail for Mickey Mouse poured into the studio on Hyperion Avenue, with postmarks from across the United States, from England, Spain, the Philippines. Some were addressed to Mickey, some to Walt.

Eric Smoodin, Film Historian: Mickey is understood as being the creation of Disney. And Disney is understood as being the father of Mickey. And combined, that makes for a kind of international stardom that we really hadn't seen before.

Don Hahn, Animator: When everybody else is suffering Walt Disney is selling consumer products, and making millions of dollars out of Mickey Mouse. And that's a huge story that this little mouse turns into the future of the Walt Disney Company.

Neal Gabler, Biographer: Walt Disney always talked about Mickey Mouse as being his alter ego. He would say that, "You know, I'm closer to Mickey Mouse than I am to anyone else."

Walt, as Mickey (archival): "Hey Pluto! Here she comes!"

Ron Suskind, Writer: Mickey and Walt are talking to each other...

Walt, as Mickey (archival): "Hey Pluto! Here she comes!"

Ron Suskind, Writer: …so he's got to do Mickey's voice. Someone's got to do it, so of course Walt does it because it's him talking to himself. "So, Mickey, how're you feeling today?" [Mimics Mickey Mouse] "You know, I feel great. Do you know it wasn't an easy day? You know, maybe tomorrow, who knows? You know, let's get into a little bit of trouble. You and me."

Narrator: Walt Disney was not yet 30, and he had made himself the first celebrity of animation -- a film cartoonist the public could name. His studio stood atop the industry, and was growing to meet the demand for new Mickey cartoons. The success of Mickey lured plenty of good talent to Hyperion, some of the best in the business, but Disney insisted on having the final word on every foot of finished film that came out of his studio.

He spent long hours at the office -- often until one or two o'clock in the morning -- and still had a hard time keeping up. He was anxious and obsessive, chain-smoking day and night, drumming his thumbs impatiently on the table in story meetings.

Michael Barrier, Writer: His role was changing in the studio. He was leaving behind the things that were so familiar to him -- working with his hands, being an active participant in the work -- becoming more and more a man who was the intellectual overseer, evaluating, criticizing, editing. And as he stepped back from this more active participation, he initially was, I think, very distressed by it, felt uncomfortable doing it.

Narrator: Walt had talked of having a big family of his own for years. He wanted 10 children, he would tell his sister, and he would spoil them all. Lillian had her doubts about raising any number of children, especially when she considered the office hours Walt kept. But he talked her into it -- Roy and Edna had had their first child, already -- and by the spring of 1931, Lillian was pregnant. Walt was giddy. He was already making plans for a bigger house to accommodate the new addition.

Then Lillian miscarried. Disney waved off the well-wishers and sympathizers. He threw himself back into his work. He insisted he was fine. He was not.

Walt Disney (archival audio): In 1931 I had a hell of a breakdown. I went all to pieces. It was just pound, pound, pound. And it was costs. My costs were going up. I was always way over whatever they figured the pictures would bring in. And I cracked up. I just got very irritable. I got to the point that I couldn't talk on the telephone. I'd begin to cry, and the least little thing, I'd just go that way.

Narrator: In October 1931, Walt Disney took his doctor's advice and escaped on the first real vacation of his life. He and Lillian went across the country to Washington, D.C., then to Key West, and on to a week's stay in Cuba. They rode a steamship through the Panama Canal on the way back to Los Angeles.

Once home, Disney told people that the breakdown had been a godsend. Life was sweet, he said, and there was more to it than work. He dove into a new exercise regimen, went with Lillian on long horseback rides, learned to play polo, and joined a league.

Neal Gabler, Biographer: Walt comes back from his nervous breakdown and he does change his lifestyle. But does Walt Disney withdraw? Does he delegate? Does he do the things that one might have expected him to do? No, he does not.

Narrator: Disney had never been shy about spending money on his vision, even when the studio was cash poor. He had already used up his earliest Mickey profits in the creation of a new series of cartoon shorts called Silly Symphonies.

Eric Smoodin, Film Historian: The Silly Symphonies were much more about animation as art. So The Skeleton Dance and others like them were understood as these wonderful almost avant-garde films that merged music and dance, and made characters out of nature and also other kinds of inanimate things in ways that people hadn't really seen before.

Narrator: Silly Symphonies raised Walt to near mythic status among cartoonists and animators. Artists from all over the country packed their bags and headed for California, just for the chance to work with the great Walt Disney. The Hyperion staff grew to nearly 200. Men ruled the studio, as they did all studios in the 1930s; the women who came to work at Disney were relegated to the low-wage ink-and-paint department. In the middle of the Great Depression, few complained about a steady job with steady pay.

Sarah Nilsen, Film Historian: It becomes like the studio to work at. And all of those animators just thrive because Disney sets it up as a legitimate profession. "Here I step in. I will recognize your talent. I will pay you well."

Robert Givens, Animator: It was like a renaissance to us, you know. It was a flowering of the animation industry. It'd never been done before. This was fine art, you know, not just dumb cartoons.

Narrator: Disney's new series was the test ground for innovation, with firsts in sound technique, color and multi-plane camera technology, which produced a three-dimensional depth never before seen in animation.

Neal Gabler, Biographer: Walt intended the studio to be the place where you created great art. That was so instrumental to Walt's understanding of the studio. And that became, in many ways, the most powerful element in how he dealt with his workers. They wanted to produce great things. He made them want to produce great things.

Tom Sito, Animator: He was very jovial. He was very informal. He's the one who first insisted on only being referred to by his first name.

Ruthie Tompson, Ink and Paint Artist: Boss? He wasn't boss. He was a friend. And everybody called him Walt. If they didn't call him Walt, that was the end of that one.

Robert Givens, Animator: We used to play volleyball at noon, over there across the street in the annex. And Walt used to come over there and watch us, you know. He used to say, "Don't play too rough," he'd say. And he wanted us to be careful, not hurt our hands, our drawing hand, particularly. And we loved to win, because then he'd applaud. But he was the big daddy there. He didn't miss anything.

Narrator: Disney offered drawing classes at the studio, and brought in professors from the Chouinard Art Institute to teach them. He invited experts to lecture on Impressionism, Expressionism, Cubism, the Mexican Muralists.

Don Hahn, Animator: He was always very much about not only hiring the artists, but providing a safe place for them to do their job. And by "safe," I mean a place to make mistakes, and a place to fail, and a place to take criticism without the fear of being fired, and a place to be able to learn.

Ron Suskind, Writer: He wanted a family, a community, a place. "I can actually create a little world, bordered, mine, just what I need it to be. Inhabited by all these people. A community marked 'Disney.'"

Narrator: Walt Disney, not yet 35, appeared to be in possession of the magic beans; his studio was a Technicolor rainbow in the middle of the pale, gray Depression-era America. His home life was thriving too: Lillian had given birth to a daughter, Diane, and the Disneys would soon adopt a second daughter, Sharon. But Disney wasn't satisfied. He needed a "new adventure," he would say. "A kick in the pants to jar loose some inspiration and enthusiasm."

Disney's employees were still telling the story decades later: One evening in 1934, Walt sent his entire staff out for an early dinner, but told them to hurry back to the Hyperion soundstage for an important company meeting. The room was buzzing by the time Walt took the stage.

Neal Gabler, Biographer: Disney is lit on the sound stage, and he then proceeds to act out -- alone, just him, a one-man show -- the story of Snow White.

Steven Watts, Historian: What he did was to go through the whole movie as he saw it, acting out all of the parts, impersonating all of the characters, going through all the emotions, all the ups and downs -- the queen, the princess, the seven dwarves, even the animals.

Narrator: What Disney was proposing had never been done, never even been tried: a feature-length, story-driven cartoon.

Steven Watts, Historian: Roy Disney was pretty skeptical about all of this. And the more he thought about it, actually, the more convinced he became that this could be a disaster for the studio because he was afraid that, it wouldn't sell, that people wouldn't see it, and it would drag the studio down into bankruptcy. And Roy dug in his heels.

Narrator: Walt would not let it go. He was convinced this century-old Brother's Grimm fairy tale about a virtuous princess chased into a deep, dark forest by her hateful stepmother was a can't-miss proposition.

Neal Gabler, Biographer: He must have told that story after that first night, you know, a thousand times. People would always say he'd collar them in the hallway and tell the story of Snow White again. He'd have to repeat it again and again and again, to keep them energized, to keep himself energized, and to review the film in his head so that it was always rolling. This was obsession.

Narrator: Walt's excitement was catching. "We were just carried away," remembered one animator. "I would've climbed a mountain full of wildcats to do everything I could to make Snow White."

Roy grudgingly came around and managed to shake the money free from their longtime lender, Bank of America. But he warned his brother the bankers were very nervous about this gamble, and they expected Walt to stay on schedule and within the agreed-upon budget. The schedule, the budget, the company's debt were secondary considerations to Walt, who was preoccupied with a single overriding problem: how to translate his idea to the big screen. Snow White would have to captivate its audience in a way no cartoon ever had before.

Neal Gabler, Biographer: In the shorter cartoons, you can make people laugh. And the gag is the basic component of these things. You get people to laugh. But Walt Disney now is asking another question: Can you make people cry? Can you make people cry over a drawing?

Narrator: One key, Disney believed, was to infuse his animated film with a natural realism. He brought live animals into the studio so his artists could study their movement. He had his animators throw heavy objects through glass plate windows just to analyze the shattering effects. Disney hired a teen-age dancer to act the part of Snow White -- so his animators could study how she looked when she leaned over, or laughed or smiled; so they could see the movement of her dress as she danced.

Steven Watts, Historian: They would bring in actors and they would have them impersonate these characters in front of the animators, who would try to capture certain qualities of their movements. They would even film them to try to get a sense of personality, of movement, of realism.

Michael Barrier, Writer: What he was after was something different, making thought and emotion visible in a way that seems natural and not artificial.

Tom Sito, Animator: Disney really kind of took the art of animation and pushed it towards the animator as an actor and about performance. He wanted his animators to take acting classes. Studying their facial muscles, how you say certain words, you know. How is your lips shaped when you say, "V," or how is like, "O," or "Ooh"? You know. You know, how does it affect your eyes?

Richard Schickel, Writer: There were no rules. They hadn't been invented before. So, you're kind of free to do anything you wanted to do. Follow your instincts and do it.

Narrator: Walt's stubborn insistence on getting the story right, on innovation, and on attention to detail meant the pace of production at Hyperion was glacial.

Neal Gabler, Biographer: To draw each of these characters, to draw these backgrounds, to do it in a way that transcends anything that had been done before, is excruciating. It's grueling. It's painful. It's tormenting.

Robert Givens, Animator: We were the crew that did most of the Snow White drawings. And we'd sometimes take a whole day for a close up of Snow White. That's how intricate the drawing was. It was so precise. It was like making watches, you know. It was just such fine detail. You know, one little line'd throw the whole thing off.

Narrator: The production process did not change: key animators would draw the main characters in Snow White. "In betweeners" would draw the movements between the key frames. The ink-and-paint artists would add color to the drawings and transfer them to the transparent sheets -- or cels -- to go to camera. At 24 frames per second and often multiple cels per frame, Snow White would require more than 200,000 separate drawings.

Eric Smoodin, Film Historian: Making the film required an army of people. And I'm not sure that Disney thought of all of them as talent. There are real workers here who are doing the grunt work.

Narrator: The Disneys had already built a two-story addition at Hyperion, but it wasn't near enough. Roy was forced to rent bungalows and other buildings in the neighborhood, just to accommodate their staff, which grew to more than 600 people.

Don Hahn, Animator: Poor Roy Disney. You know, he's, during this time there's tremendous expansion, and ideas, and excitement by everybody. But Roy's the banker and he's the guy that has to keep it all together. And, and there's weekly discussions about how to make payroll. The feature was going over budget. The bankers from Bank of America were there frequently. And Roy's job was to keep everybody calm and to keep it all together financially.

Snow White (archival sketches): Supper!

Seven Dwarfs (archival sketches): Oh yay! Yay, yippee, yay...

Narrator: As the production dragged into its second and then its third year, Walt's demands began to look dangerous. He repeatedly pushed deadlines, and by the start of 1937, with the premiere set for that December, the studio was behind -- way behind. Ten months to the premiere date, and not a single animation cel had been shot on film. But Walt insisted that Snow White could not be rushed, and could not be done on the cheap.

Walt kept upping the ante, which meant Roy had to raise Walt's original budget number six times over. The trade papers were beginning to write stories about the delays; people were calling Snow White "Disney's Folly." Roy was worried they might be right.

Ruthie Tompson, Ink and Paint Artist: I was working the 12-hour deal, where you come in at eight and go home at eight. And we really were cleaning cels and patching cels, fixing mistakes and things like that. There were a lot. And the queen, the queen was -- she had the kind of paint that was kind of sticky. And so those things would come back from camera, and we'd have to clean them up and patch them and send them back to camera.

Don Lusk, Animator: I worked my tail off. I was put in charge of the clean up and in-betweens. That's where it was lagging. We went in at seven instead of eight. And we went to dinner and we came back and usually worked till almost 10.

Robert Givens, Animator: The ink-and-paint gals were, you know -- some of them were losing their eyesight. It was a hell of a thing. They were just slaves. They were doing it, but they believed in this thing so much, they were going to drop dead on the job.

Narrator: The animators finished in early November, but the last cels weren't painted until November 27th. Rumors were flying around Hollywood that there would be no print of the film ready for the December 21st premiere.

Newsreel (archival): Blasé Hollywood, accustomed to gala openings, turns out for the most spectacular of them all: the world premiere of the million and a half dollar fairytale fantasy Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. Replicas from the first feature cartoon thrill thousands who turn out for a glimpse of lovely Marlene Dietrich with Doug Fairbanks Jr. and a parade of stars. Shirley Temple is just as enthralled as are the grownup stars and moviegoers with the seven fantastic dwarfs.

Neal Gabler, Biographer: Walt was in a state of high anxiety. He had no idea how the audience was going to respond.

Reporter (archival audio): Well Walt, I think you're due to do all the talking tonight. Tell us a little bit about this picture will you?

Walt Disney (archival audio): Well, it's been lot of fun making it and we're very happy that it's being given this big premiere here tonight and all these people are turning out to take a look at it. And I hope they're not too disappointed.

Reporter (archival audio): Well I'm sure they won't be, I've seen the picture Walt...

Steven Watts, Historian: He didn't know if it would really work. And one part of him was almost agonizing over "Well, if people don't buy this, this will just fall flat, and then I will be done."

Narrator: Audience members gasped at the opening shots of the Queen's castle.

Evil Queen, Snow White and The Seven Dwarves (archival): Slave in the magic mirror. Come from the farthest space, through in from darkness I summon thee -- Speak!

Narrator: They howled in laughter at the antic dwarfs.

Dwarves, Snow White and The Seven Dwarves (archival): Ah, soup! Hooray!

Snow White, Snow White and The Seven Dwarves (archival): Uh-uh-uh, just a minute!

Evil Queen, Snow White and The Seven Dwarves (archival): The heart of a pig! And I've been tricked.

Narrator: They hissed disapproval at the Evil Queen. And still, Walt was anxious.

Evil Queen disguised as Old Woman, Snow White and The Seven Dwarves (archival): Don't let the wish grow cold!

Snow White, Snow White and The Seven Dwarves (archival): Oh, I feel strange...

Narrator: He sat gripping Lillian's hand for nearly 75 minutes, nervously anticipating the scene that would put the power of his personal vision to the ultimate test.

Snow White, Snow White and The Seven Dwarves (archival): Sigh

Evil Queen disguised as Old Woman, Snow White and The Seven Dwarves (archival): [Cackling laughter] Now I'll be fairest in the land!

Narrator: When it arrived -- the apparent death of Snow White -- the theater was hushed.

Seven Dwarfs, Snow White and The Seven Dwarves (archival): [Quiet crying and sniffling]

Neal Gabler, Biographer: The audience started weeping. And that's when Walt knew. That's when they all knew. The audience had suspended its disbelief so thoroughly, so believed in the reality of the situation and of the dwarves, that they were crying. That was really the triumph of the film.

The Prince, Snow White and The Seven Dwarves (archival audio): One song, only for you. One heart, tenderly beating...

Ron Suskind, Writer: Clark Gable and Carole Lombard are weeping. They don't know what hit them. You know, what hit them is that they crossed a barrier, from the life they live to the internal world where myth lives in all of us, and Disney provides the passage. And it ain't kid's stuff.

Narrator: When the curtain came down the audience rose from their seats and broke into a thunderous ovation. "I could not help but feel," one rival movie producer gushed, "that I was in the midst of motion picture history."

Richard Schickel, Writer: I know the first movie I saw was Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. Now, I didn't know anything but to be delighted with it. It was wonderful. I mean, I still think it's wonderful.

Evil Queen, Snow White and The Seven Dwarves (archival): Snow White lies dead in the forest...

Ruthie Tompson, Ink and Paint Artist: I loved the queen. She was so awful. But she was just beautiful.

Evil Queen, Snow White and The Seven Dwarves (archival): …Behold her heart.

Ruthie Tompson, Ink and Paint Artist: She was so beautifully drawn and everything.

Richard Schickel, Writer: Kids had to be carried screaming out of Radio City Music Hall; they're too frightening for them. That's an important aspect: Disney understood that kids could take more scariness than people thought they could take. So they wet the pants and wet the seat in Radio City Music Hall. But they'd had an experience. You know? That what was important. It was not just bland. It was serious stuff going on in their little heads.

Ron Suskind, Writer: Think about what he does. Well he's like, "Ha! These cartoons don't have to be just slapstick. They can carry everything, all the biggest stuff. They can carry ancient and powerful mythologies. They can carry everything."

Evil Queen, Snow White and The Seven Dwarves (archival): Look! My hands!

Ron Suskind, Writer: That was a huge leap. And that's an artistic leap. He's creating a new art form.

Narrator: Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs played at New York's Radio City Music Hall for five straight weeks at the beginning of 1938; no other film had ever run more than three weeks there. National and international releases followed. Lines wrapped around small-town theaters in New England, the South, the Midwest, the Far West. The film was a box office smash in London, Paris, and Sydney. It grossed $8 million in its first year -- the equivalent of over 100 million today, and more than any film before it. Roy paid off the studio's $2.3 million debt to Bank of America, while the film was still in its first run, and helped oversee an unprecedented merchandising campaign.

Eric Smoodin, Film Historian: There are Snow White jars, and Snow White jelly, and Snow White scarves. There are Snow White shows going on at department stores. So the film and the space of commerce are completely one. It's a commercial triumph for Disney, not just because of the film itself, but because of the way that the merchandise is tied to it.

Narrator: Walt Disney was celebrated as a true American original -- a man capable of harnessing the power of technology and storytelling; a man adept at art and commerce. Harvard University gave him an honorary Master of Arts, and so did Yale, whose trustees called Disney "the creator of a new language of art."

Ron Suskind, Writer: He's hailed in Paris. He's hailed in New York. He's living a dream. And that's a moment where he starts to think very boldly. He almost is released from hesitations. He's like, "I am that guy that I dreamed of. I am him. So now what do we do?"

Narrator: Disney cultivated the look of the artist in public, but at home, he was just plain Dad. Walt made a point to drive his two young daughters to school every day, chased them around their house cackling like the Wicked Witch, and read them bedtime stories.

Neal Gabler, Biographer: There's no question, he adored them. Absolutely adored them. He was a man who had a lively sense of play that he'd never lost from the time he was a child.

Steven Watts, Historian: He was very domestic, very nurturing in a way that usually in that day and age was associated more with Mother's role. Lillian was a bit aloof, a bit reserved, a bit cool, even with her children, and Walt was just the opposite. He was overflowing with enthusiasm. I think, in a way, he was reacting against his own childhood and against Elias, because Elias was so stern with him. Disney often said, "I want to spoil my children terribly. I just want to spoil them."

Narrator: He had had only sporadic contact with his own parents since his move to California. But the Disney studio's new financial success afforded Walt the chance to draw them closer. Walt and Roy moved Elias and Flora to Los Angeles, and, as a 50th wedding anniversary present, the brothers bought them a house. In the middle of the Snow White frenzy they also threw a golden wedding anniversary party, which they deemed worthy of preserving for history.

Walt Disney (archival audio): Well, here it is: 1937. And you folks are almost ready to have your, celebrate your 50th wedding anniversary.

Flora Disney (archival audio): We're not a'gonna celebrate.

Walt Disney (archival audio): Why not?

Flora Disney (archival audio): Oh, what's the use?

Walt Disney (archival audio): Well, Dad likes to celebrate. He's always enjoyed a good time.

Flora Disney (archival audio): We've been celebrating for 50 years. Gettin' tired of it.

Walt Disney (archival audio): What about you Dad? Don't you want to make a little whoopee on your Golden Wedding anniversary?

Elias Disney (archival audio): Oh, we don't want to go to any extremes with it a'tall.

Walt Disney (archival audio): Well, I expect you, I hoped you wouldn't go to any extremes if you're whoopeeing it up.

Flora Disney (archival audio): He don't know how to make whoopee.

Narrator: Walt sometimes seemed compelled to talk about the old days; even as his fame grew, his family's early struggle remained a touchstone. He held fast to the idea of himself as a man formed in the crucible of want and deprivation in the great forgotten middle of the country.

Carmenita Higginbotham, Art Historian: He feels it very important to identify and to make note of his Midwestern background, and to propagate that story. He understood the value of labor, and that that is not something he learned about from somebody else, rather it's naturally who he is.

Narrator: Walt Disney had been a player in the movie business for more than 15 years, and a celebrity for nearly 10, but the acclaimed filmmaker still did not think of himself as a Hollywood insider. He complained that other major film producers refused to acknowledge animation as serious cinema. And he wasn't wrong. When the Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences announced the 10 nominees for the Best Picture of 1938, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs was not on the list.

Instead, Disney was given a special Oscar for his pioneering work in feature-length cartoons.

Shirley Temple (archival): I'm sure the boys and girls in the whole world are going to be very happy when they find out the daddy of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Mickey Mouse, Ferdinand, and all the others is going to get this beautiful statue. Oh, isn't it bright and shiny?

Walt Disney (archival): Oh, it's beautiful.

Shirley Temple (archival): Aren't you proud of it Mr. Disney?

Walt Disney (archival): Why, I'm so proud I think I'll bust.

Carmenita Higginbotham, Art Historian: He got the, sort of the honorable mention, which is... crap. He doesn't want that. He has created something absolutely magnificent. He knows it's magnificent. Audiences have told him it's magnificent. He believed in this so much, he put himself personally on the line for his films, and his products, and for animation, and the furthering of animation. And Hollywood just didn't seem ready to view animation as art or as filmmaking. It had to have smarted.

Narrator: Disney had dreams of producing a new feature-length animated film every six months -- and almost all from source material that played to his strengths: fairy tales, folktales, or popular novels already familiar to his audience. His two projects following Snow White were coming-of-age stories: first up was Bambi, based on a novel about a young deer becoming a stag; and then Pinocchio, a popular late 19th century Italian folktale about a wooden puppet who wants to be a real boy.

Disney hit snags right away on Bambi, and began to worry the story was too complicated and needed more time in development. So he moved Pinocchio to the front of the production line -- and hit more snags.

Neal Gabler, Biographer: They struggled mightily with the story of Pinocchio. As Walt himself said, he's not a very nice puppet in the original story. He's kind of a wiseacre. So there was something they had to tackle immediately, which is: How do you make this puppet into someone likable?

Narrator: Disney was still puzzling out the Pinocchio story in the fall of 1938 when the phone call came. His parents had suffered carbon monoxide poisoning caused by a malfunction of the heating system at the house Walt and Roy had bought for them.

Elias had survived; Flora had not. Walt went to her funeral, and then he went back to work. He never talked of his mother's death again.

Sarah Nilsen, Film Historian: It was something he dealt with, within himself as a private matter. Even with his wife I don't think that relationship he shared very much. His emotions were internalized. And that's why cinema I think offered this way to emote in a way that he couldn't emote in his own private life.

Neal Gabler, Biographer: Walt Disney once exploded during a story session and he pounded on the table. And he said, "We're not making cartoons here! We're not making cartoons." Walt Disney had made this separation between Mickey Mouse and some of the early Silly Symphonies -- they're cartoons. But now we're not making cartoons. We're making art. And art has a higher standard. And the standard is the emotional response that we get from people. Can you make them feel deeply?

Ron Suskind, Writer: Art doesn't work unless it gets to the big stuff. Call it what you will. Entertainment doesn't work unless it gets at the core, the stuff that we really, really wrestle with, make you laugh, make you cry, make you sing, make you sigh. But you got to get at it.

Narrator: Disney wasn't thinking small on Pinocchio. Snow White had proved that his animated films could tackle the sweep of the human condition, with all the light and shadow of real life. Now, he went deep inside himself for inspiration and emerged with a magical story elixir that became the Disney trademark -- outsiders struggling for acceptance, coming-of-age heroes bucking authority, temptation, loss, redemption, and survival.

Don Hahn, Animator: So now Walt's wading through the story throwing things out left and right and saying, "What's the essence of it? What's this story about? Who's it about? Why do I care? Why do I want to watch this?"

Douglas Brode, Film Historian: Pinocchio becomes about what it means to be human, about how you have to achieve humanity. You have to earn it.

Don Hahn, Animator: They take huge liberties. Walt Disney doesn't care. He says, you know, "We're taking the title, we're taking the puppet thing, and we're going to make that into our story."

Narrator: Difficult as they were and engaging as they were, Pinocchio and Bambi did not capture Walt's undivided attention. There was an enticing new experiment going on right down the hall. The project had begun as a cartoon short based on a symphony titled "The Sorcerer's Apprentice," starring Mickey Mouse, with the backing of an orchestra conducted by the celebrated Leopold Stokowski.

Disney was so taken with the first results that he decided to expand it into a feature-length film -- Fantasia. He and Stokowski selected eight separate classical symphonies, and Walt and his team began thinking about imagery to match. The Disney Studio was crawling with musicians, dancers, even famous scientists like the astronomer Edwin Hubble.

Don Hahn, Animator: So here's Stravinsky, and George Balanchine comes by the studio, "Well, let's choreograph some dancing for us." So these experts are coming and going, and there's a ballet company in the next room dancing. And here's Hubble talking about theories of deep space, and where the cosmos came from. And there's a dinosaur expert. And it is this cultural kind of petri dish of people together working and collaborating creating Fantasia. And he loves it because this is a huge fun sandbox.

Neal Gabler, Biographer: Well, he's dealt with realism and realistic emotions, but now he's trying to get to emotion in a different way, circumventing realism. This is absolutely alien to the Disney process, to try and see if you can reach emotion directly through abstraction.

Ron Suskind, Writer: He's saying, "I want to try what heroes of art do. You know, I want the great artists of the time to join in here. You know, I want to create art that lasts centuries."

Narrator: The Disney studio ran to the rhythms of Walt's bursting energy, which appeared to be spilling beyond rational boundaries. The boss had three major productions spinning simultaneously and had nearly doubled the number of full-time employees. The Disneys were in dire need of space to house their thousand-plus staff, and another addition at Hyperion was not going to cut it.

Without consulting with Roy, who was in Europe at the time, Walt selected a 51-acre building lot, empty but for a polo field, on the other side of the Hollywood Hills, in Burbank. Then he went to work making his dream studio.

Neal Gabler, Biographer: It was designed for absolute efficiency, but also to engender this wonderful sense of community. In fact, there was one point where he said, "You know what'd be great, is if we build an apartment complex here on the studio lot, so no one ever has to leave." It's so that his employees could become part of this very insular community where they would all work together in this common mission to make these great animations. And that's what this new studio was really all about. It was really all about creating a perfect place to create perfect films.

Narrator: The day after Christmas, 1939, most of the Disney staff began the move from Hyperion to Burbank. The heart of the studio campus was the three-story animation building, with Walt's office on the top floor. Each animator had a single big airy sunlit room to himself, with an oversized work table, a stylish area rug, an easy chair to recline in, and drapes. The entire facility was air-conditioned. Landscaped pathways led to a theater, a restaurant, a soda fountain.

Don Lusk, Animator: It was wonderful. We had things that we'd never had before. If you wanted a milkshake, you'd call the little coffee shop right in the middle of the place. And then they had runners that would run these things into us, a sandwich, whatever we wanted. It was just heaven.

Tom Sito, Animator: It had a cafeteria. It had a gymnasium with an ex-member of the Swedish Olympic team as a personal trainer. The studio had its own gas station. You know, you could get, you could get your car repaired, you know, while you're at work. This is amazing.

Jiminy Cricket, Pinocchio (archival): [singing] Like a boat out of the blue, fate steps in and sees you through…

Narrator: By the time the studio was ready to launch Pinocchio in New York City in February of 1940, Walt Disney was selling hard.

Jiminy Cricket, Pinocchio (archival): [singing] ...Your dreams come true!

Narrator: He was singing the praises of Jiminy Cricket -- Lord High Keeper of the Knowledge of Right and Wrong.

Jiminy Cricket, Pinocchio (archival): [singing] Give a little whistle, yoo-hoo! Give a little whistle, woo-hoo! And always let your conscience be your guide.

Pinocchio, Pinocchio (archival): And always let your conscience be your guide!

Narrator: He was also talking up the studio's breakthroughs in camera technology and special effects.

Blue Fairy, Pinocchio (archival): Wake! The gift of life is bound.

Pinocchio, Pinocchio (archival): Father!

Narrator: "For the first time in the field of animation," Disney proclaimed, "audiences will see, in Pinocchio underwater effects that look like super-special marine photography."

Pinocchio, Pinocchio (archival): Can you tell me where we can find Monstro? Gee! They're scared!

Tom Sito, Animator: You really have to stop yourself and say, "This was all blank paper. This all began as blank paper. It doesn't exist." You know, we believe it's water, and we believe those characters are real, and that's the summit of the animator's art. That's the pinnacle of what we call personality animation, which is creating a completely artificial world that we accept.

Pinocchio, Pinocchio (archival): Father!

Stromboli, Pinocchio (archival): Mmmm. You will make lots of money for me!

Richard Schickel, Writer: Pinocchio has richness and dimensions that other animated cartoons don't have.

Stromboli, Pinocchio (archival): And when you are growing too old, you will make good firewood!

Richard Schickel, Writer: I mean, he's swallowed by a whale, for Christ's sake. He is in peril throughout the movie.

Jiminy Cricket, Pinocchio (archival): Hey! Blubber mouth! Open up, I got to get in there!

Richard Schickel, Writer: And at the same time there's Jiminy Cricket, you know, who's delightful and charming and takes some of the sting off of this movie. But that's a pretty dark movie.

Carmenita Higginbotham, Art Historian: Pinocchio is just a wooden boy who's trying to be human. One would think that that means he can make mistakes, that he would be allowed to have the faults of being a boy.

Lampwick, Pinocchio (archival): Please! You got to help me!

Carmenita Higginbotham, Art Historian: And instead any indiscretion is met with the possible death of his adopted father or the transformation into a donkey. The stakes are so very high.

Lampwick, Pinocchio (archival): Hee-Haw! Hee-Haw!

Pinocchio, Pinocchio (archival): Oh! What's happened?!

Jiminy Cricket, Pinocchio (archival): I hope I'm not too late!

Pinocchio, Pinocchio (archival): What'll I do!

Ron Suskind, Writer: Pinocchio is seeking a home. He's seeking identity. He's seeking place. He wants to be real.

Blue Fairy, Pinocchio (archival): Prove yourself brave, truthful and unselfish, and someday you will be a real boy.

Ron Suskind, Writer: That's what the goal is. I want to feel my life most fully. And then once I feel my life I will have a chance to feel the big truths, the things that give us sustenance.

Pinocchio, Pinocchio (archival): I'm alive, see! And-and I'm - I'm - I'm real. I'm a real boy!

Geppetto, Pinocchio (archival): You're alive! And-and you are a real boy!

Jiminy Cricket, Pinocchio (archival): Yay! Whoopee!

Geppetto, Pinocchio (archival): A real live boy! This calls for a celebration!

Narrator: Audiences across the country walked away from Pinocchio emotionally drained, and enormously satisfied. The critics raved. "[Walt Disney] has created something... that will be counted in our favor -- in all our favor -- when this generation is being appraised by the generations of the future," the New York Times's movie critic wrote.

Jiminy Cricket, Pinocchio (archival): Well! This is practically where I came in.

Narrator: "For it will be said that no generation which produced a Snow White and a Pinocchio could have been altogether bad."

The downside of Pinocchio was apparent from the jump too. Walt's insistence on innovation had pushed production costs to nearly twice that of Snow White, and the picture was not going to earn back the investment. Ticket sales in the United States were slow; in Europe now at war, they were moribund.

The Disneys had burned through more than $2 million of the net profits from Snow White, while borrowing heavily from Bank of America to fund the dream studio in Burbank.

Neal Gabler, Biographer: Walt Disney is kind of under the gun. The costs of Fantasia and Pinocchio, and even Bambi in its early stages, are enormous. And the war has cut off the European market. So Walt Disney has lost a giant market, and he is worrying about how he can finance all of these films under his new project to make feature films constantly, one every six months or so.

Narrator: Roy Disney had a plan: they would go public and issue shares in the company. His kid brother wasn't happy at the thought of shareholders sticking their noses in his creative process, but he saw little choice.

In April of 1940, as the last of the staff made the transition to the Burbank Studio, Walt Disney Productions issued 155,000 shares of preferred stock, netting the company nearly $4 million. Roy and Walt had both signed seven-year contracts as part of the deal. Roy was guaranteed a salary of $1,000 a week, and Walt $2,000. The company reassured investors by taking out a $1.5 million life insurance policy on its key asset: Walt Disney.

Steven Watts, Historian: Fantasia opens with the Bach Fugue and Toccata in D minor, but it is pure abstraction, no characters, no nothing recognizable in the natural world, which gets the movie off in a very interesting vein.

Carmenita Higginbotham, Art Historian: Fantasia is wildly ambitious. You can feel it in every scene but it's very uneven.

Steven Watts, Historian: When the movie worked, it's spectacular. When it didn't work, it's sort of dumb. The critical reaction was extremely divided. Some people thought Disney had pulled off this alliance of visual art and music, and created something new and compelling. Other critics thought that it was a disaster. And they slammed the movie very, very hard for dragging classical music traditions down into the dust.

Neal Gabler, Biographer: Walt Disney had made his reputation in the intellectual community as being unpretentious. And when he makes Fantasia, guess what? He's pretentious.

Carmenita Higginbotham, Art Historian: Fantasia raises a number of questions as to if Walt is stepping beyond himself, if he's not appreciating his limits. And Walt will take this personally.

Steven Watts, Historian: He didn't handle criticism very well, ever. And the criticism over Fantasia, I think, really rankled. And what it did was to encourage a kind of anti-intellectualism that was always there with Disney, but I think increasingly he drifts in the direction of: "These are eggheads. They don't know anything about ordinary people, and to hell with them."

Narrator: Fantasia's financial losses were far greater than Pinocchio's, largely because so few theaters had the expensive new sound system Disney required to show his film-symphony. The deficits left the company unable to pay its guaranteed quarterly dividend to preferred shareholders. And the expensive new studio was already starting to feel more like a dropped anchor than a sail spread wide to catch the creative winds.

Steven Watts, Historian: The new Burbank studio was a kind of a case study in "be careful what you ask for." It was so nice that it was almost sterile. It was all rationalized. It was all organized. And something, the quality of the creative experience, was almost designed out of the operation.

Narrator: There was something unmistakably mechanical at the heart of Walt's workplace utopia. People were segregated by task, as at an industrial plant. Company hierarchy was more rigid, more obvious, and more carefully policed by Disney administrators.

The tonier perks accrued to the highest links of the corporate pay-chain. Membership in the Penthouse Club, with its gymnasium, steam room and restaurant, was reserved for top writers and animators -- all men still. So were office niceties like area rugs, drapes, easy chairs and armoires.

When animator Don Lusk started doing friends a favor by picking up the slack on lower-level jobs like clean-up and in-between, somebody above took note.

Don Lusk, Animator: I came into the room on a Monday morning and all that was in there was a desk. The rug was gone. The coat closet was gone. My easy, foldout chair was gone. Everything was gone excepting my desk and a chair. I called up and I said, "What the hell is going on?" And, they said, well, I'm not animating so you don't get a rug on your floor.

Robert Givens, Animator: Yeah, I missed the old Hyperion place. It was beginning to feel like corporate America, you know? It was just getting too big and losing the family touch.

Neal Gabler, Biographer: The studio had grown so rapidly that there were all of these folks in the animation process: you know, the assistant animators, the in-betweeners. They didn't know Walt Disney. And they weren't well-paid by Walt Disney, as the master animators were. I think Walt Disney's attitude was: Lookit, anybody can do that stuff. The master animators, that's one thing. But doing in-between work, why am I going to pay them top dollar? They're not artists.

Tom Sito, Writer: Some of the people who told me about the cafeteria, they said the cafeteria was wonderful, but most of the rank-and-file artists couldn't afford to eat there. They still had to go out to the sandwich wagon out on the street 'cause the salaries were all over the place. You know, I mean, there were people making $200 and $300 a week and people making $12 a week.

Narrator: Workers at the bottom of the Disney ladder were starting to grumble in 1940; now that the company's finances were public, everybody knew the boss was making five or 10 times more than the highest paid members of his creative team; and more than 100 times that of the women working in ink-and-paint.

Disney, who still insisted that all his employees call him "Walt," was oblivious to the complaints at his new studio. It was no longer common to see him wandering the halls, engaging in idle chatter, batting around story ideas. He spent most of his time in his own suite of offices, with its private bath and bedroom, and a team of secretaries standing guard at his door.

Hollywood was famous for its glamorous movie stars and directors, but it would not have functioned without the men and women working behind the scenes -- building sets, adjusting lights, drawing animation.

When federal legislation had passed in 1935 allowing collective bargaining, Hollywood's backstage hands began to organize. More than a half-dozen Hollywood unions and guilds emerged in the late 1930s to bargain for better working conditions and better pay. Among them was the Screen Cartoonists Guild, which offered representation for the animators, assistants, in-betweeners, and ink-and-paint artists working across the industry.

By 1940 the cartoonists guild had organized the animation departments at all of the major studios; except Disney's, which employed more than half the men and women working in the field of animation.

Tom Sito, Writer: Even after organizing MGM, and Warner Brothers, and Screen Gems, and George Pal, and Walter Lantz, it only came to maybe about 150 people while Disney's was like 600. If unionism was to work in Hollywood, Disney's was the ultimate battle.

Narrator: Walt Disney saw little reason to be worried. He was not like those other fat-cat studio heads, he told himself. He and his "boys," as he called his animators, were in this thing together.

Carmenita Higginbotham, Art Historian: Walt sees himself as the father of this company and that everyone who works for him believes in what they are doing, the enterprise of being animators, of being artists, and being part of a business, and part of the studio.

Neal Gabler, Biographer: "Why in the world would anyone need a union, when I'm giving you everything you could possibly want?" He didn't see paternalism in this. He saw kindness and generosity in it.

Narrator: There were plenty of people at Burbank who did not see the labor situation as Walt Disney did; and among them was one of his best animators, Art Babbitt. Babbitt had been with Disney for nearly a decade, contributing to every major film, and almost single-handedly creating the popular character Goofy. He was one of the highest salaried animators on the Burbank lot, but made little effort to hide his sympathies for other animators who had been denied on-screen credits, or for the hundreds of assistants and inkers who were barely eking out a living.

Neal Gabler, Biographer: He was rather a large personality. He wasn't subservient to Walt. He didn't have that kind of relationship to him. He was his own man, he was independent, and Walt didn't like it.

Tom Sito, Writer: Babbitt used to tell the story about a young painter who was making $16 a week whose husband had run off because of the Great Depression. And what she was doing is that she was skipping lunches because she wanted to keep feeding her family. And one day she actually fainted from malnutrition.

Narrator: Disney didn't see the problem, and certainly didn't want to hear about it. He was incensed when he learned that the Screen Cartoonists Guild was trying to organize his shop. He was certain he had the right to run his own company as he saw fit. In February of 1941, Walt decided to make his case, personally, to the men and women working for him. He gathered the staff in the only auditorium at the studio big enough to hold all 1,200 of his employees.

Walt Disney (archival audio): In the 20 years I have spent in this business, I have weathered many storms. It's been far from easy sailing, which required a great deal of hard work, struggle, determination, confidence, faith, and above all, unselfishness. Some people think that we have class distinction in this place. They wonder why some get better seats in the theater than others. They wonder why some men get spaces in the parking lot and others don't. I have always felt, and always will feel, that the men who contribute the most to the organization should, out of respect alone, enjoy some privileges. My first recommendation to the lot of you is this: Put your own house in order. You can't accomplish a damn thing by sitting around and waiting to be told everything. If you're not progressing as you should, instead of grumbling and growling, do something about it.

Narrator: Much of the staff left the auditorium infuriated. "This speech recruited more members for the Screen Cartoonists' Guild than a year of campaigning," reported one left-wing magazine.

Babbitt was now convinced Disney workers needed a real union and signed his Screen Cartoonist Guild membership card, which made him the highest-ranking Disney employee to openly challenge the boss. Walt Disney saw Babbitt's move as a personal betrayal. "I don't care if you keep your goddamn nose glued to the board all day or how much work you turn out," he told Babbitt in the hallway one day. "If you don't stop organizing my employees, I'm going to throw you right the hell out of the front gate."