Karen Karbiener, scholar: We're at this incredibly volatile time. The country is divided into two.

Allan Gurganus, novelist: And yet there was a kind of listlessness among the population, a passivity and a drift and a cynicism had infected the country.

Narrator: As the country slouched toward Civil War in the 1850s, one concerned citizen was trying mightily to wake his countrymen to the dangers of their bitterness and despond. He'd already spent his own small treasure to publish a book of poetry called Leaves of Grass. The American democratic experiment needed saving, he had implored in Leaves, was worth saving. For his effort, he'd been called "preposterous," "nonsensical," "grotesque," and "scurvy." A lesser man would have been shamed into silence. Walt Whitman determined to speak louder. He was willing to fight the tide all the way, to stand fast against derision, neglect, and the relentless undertow of his own doubt, to sacrifice his financial well being, his family, his personal life and his health — all in the service of forcing America to face its strange new self.

Walt Whitman (as portrayed by actor): Never more shall I escape Never more the cries of unsatisfied love be absent from me, Never again leave me to be the peaceful child I was before what there in the night, under the yellow and sagging moon, The messenger there arous'd, the fire, the sweet hell within, The unknown want, the destiny of me.

(On-screen text): Long Island, NY, 1823

Narrator: America's first great poet entered the world at the margins — on a working class farm on Long Island, New York, into a family that held tight to the promise of the young country. His ancestors, Walt was reminded, had sacrificed blood in the cause of American independence.

Ed Folsom, scholar: His brothers who came after him were all named after American heroes. We have George Washington Whitman, and we have Thomas Jefferson Whitman, and we have Andrew Jackson Whitman. So he grew up with George Washington and Andrew Jackson and Thomas Jefferson sitting at his table with him.

Allan Gurganus, novelist: These were the common people in the literal sense of the word. And the freedom that he found in this lack of pedigree assured his right to choose the person that he wanted to become.

Betsy Erkkila, writer: He was sensitive and even overly sensitive to what was going on around him, both in terms of people but also a very sensuous interaction with the world. And from a very early age he felt himself called to do something with this.

Narrator: As a boy, Walter Whitman Jr. had precious little time to pursue his own dreams. His father was a farmer, a carpenter and an unsuccessful real estate speculator who struggled all his life to keep his wife and eight children afloat. He took Walt out of school at age 11 to help prop up the family's meager income. The Whitmans' circumstances never lived up to their hopes, and Walter Whitman Sr. became an ever more zealous adherent of strong drink and radical politics. The elder Whitman came to see his growing streak of financial failure as the work of forces beyond his control: banking cabals, organized swindles, and the unchecked power of the propertied class. "Keep a good heart," he liked to say. "The worst is yet to come." At 21, Walt Whitman fled his father's dark shadow and set his own course in the world. "I stand for the sunny point of view," he would claim, "the joyful conclusion."

Edwin G. Burrows, historian: If you're young and ambitious and talented and artistic and you want to make your mark in the world New York was the only place to go in the United States. It was already the center of everything that was interesting.

On-screen text: New York, NY, 1841

Edwin G. Burrows: There are ships crowding the waterfront from all over the world; swarms of sailors speaking all kinds of different languages; young men rushing back and forth; clerks, counting houses, cartmen dragging loads of things. Whitman could get off the ferry there on the foot of Fulton Street and feel like he had entered the world.

Narrator: New York was a city on the rise, and Whitman was swept along by the rush of its accelerating current. He was a notable figure even in a crowd: six feet tall, with a personal presence he described as "magnetic." He was self-educated, stubbornly self-reliant, and equipped with a self-regard that bordered arrogance. He had decided, as he would later say, to "enter with the rest into the competition for the usual rewards: business, political, literary." And he set out to show the men doing the hiring on newspaper row that he could be as discriminating as they.

Allan Gurganus: He dresses in a white collar with a vest, walking stick, a big floppy Fedora, and tries to pass for a professional man of letters. And he gets into doors on the basis of how he appears. It's not his Harvard pedigree. He doesn't have one. What he has is the force of his personality and how he appears.

Narrator: Whitman sported a fresh boutinniere in his frock coat, a gold pen, and a silver timepiece, but he could not long button up his compulsion to have his say, his way == which put him in near constant opposition to society's prevailing sentiments. As a newspaperman, Walt staked out radical positions on labor issues, women's property rights, capital punishment and immigration == and he was pleased to pick fights with the hide-bound editors at rival newspapers. He brought a bare-knuckled, working-class élan to his new business, railing against the "old moth-eaten systems of Europe" so many of New York's upper class seemed intent on emulating. He called one editor "a reptile marking his path with slime wherever he goes, and breathing mildew at everything fresh and fragrant." His bosses apparently found him all but ungovernable: in just four years he apparently lost favor at the Tattler, the Daily Plebeian, the Statesman, the Mirror, the Democrat, the Sun and the Star.

David Reynolds, biographer: He got into a little bit of trouble because of he kind of rubbed up against people sometimes in the wrong way. And he also got increasingly into trouble because he didn't like being on a schedule. Some of his employers thought he was lazy.

Karen Karbiener, scholar: He wasn't the most dedicated worker. And his love of the city often led him == during lunch and after lunch == even though he had duties that would oblige him to stay in printing house row and do his thing at the various papers he worked for, he wound up hopping on the omnibus or walking up to a museum or to a bar or to the Park Theater to just see and absorb New York.

Betsy Erkkila: Whitman loved the sense of ah humanity flowing and, and huge crowds of people and events going on.

Narrator: Like Walt himself, New York was inventing itself every day, lurching toward a destiny it had yet to fully imagine. The pull of the emerging city captured Whitman, and compelled him to record in his personal notebooks what he heard and saw and felt as he walked nights among the throng, under gas-lamps that made Broadway a shimmer of white light, or as he ducked into the narrow, dark streets of the notorious Five Points slum. He noted the museum of Egyptology and the tenement house; the waterworks and the corner saloon; the lavish opera, the rowdy Bowery theaters, and == from his seat atop the omnibus, with breeze in his face == the daily human drama of the city streets.

Karen Karbiener: He's assembling these collages of what he sees. And he's also obviously interested in a lot of the guys that he's checking out. So we've got these marvelous lists of whoever was taking his fancy at the time.

Allan Gurganus: He liked cab drivers. He liked the guys who had been in the sun all day and had brown faces, who were powerful enough through the shoulders to reign in the horses that were required to drive one of these immense cabs down the streets of Broadway.

Narrator: He made it his practice to climb into the navigator's chair on the omnibus, where he chatted up drivers like Broadway Jack, Yellow Joe, Balky Bill, Old Elephant and his brother Young Elephant, Big Frank, Patsy Dee and Tippy.

Walt Whitman (as portrayed by actor): They had immense qualities, largely animal == eating, drinking, women == great personal pride. How many hours, forenoons and afternoons == how many exhilarating night-times I have had, riding the whole length of Broadway, listening to some yarn (and the most vivid yarns ever spun, and the rarest mimicry) == or perhaps I declaiming some stormy passage from Julius Caesar and Richard (you could roar as loudly as you chose in that heavy, dense, uninterrupted street-bass.)"

Edwin G. Burrows: The sound would have been amazing. Iron rimmed wagon wheels clanking across cobblestones. It was a frightful din. There are thousands and thousands of horses. And they leave tons of manure on the street every day. Hundreds of gallons of, of horse piss every day is deposited on the street of New York. Nobody collects that. There is no sanitation department in 19th century New York. What you have is swarms of pigs basically who roam around the streets gobbling up whatever they can find. In about July or August the smell of New York is overpowering.

Ed Folsom: The dirt, the rubbish, the filth that a growing population is producing == how to deal with this, how to get rid of it == how to begin to control everything from animals walking the street to the housing for the endless number of people entering the city and growing numbers of immigrants.

Narrator: Walt saw the frantic and furious efforts being made to tame the frightening mass of new arrivals, to fit them up to be worthy citizens of the American republic. But with as many as two thousand foreign-born people entering New York in a single day, the job was beyond anybody's doing. Strong voices opined that this new wave of uneducated immigrants should simply be excluded from the body politic.

Edwin G. Burrows: Very often you'd find genteel writers who would write about the good old days of the city when it was small, when it was intimate, when everybody knew everybody, when everybody knew who was in charge and everybody respected everybody.

Karen Karbiener: I think about Edgar Allan Poe, for instance, or, or Melville, a native New Yorker who actually really didn't like the city. All they saw were the poor crowds of immigrants, the dirtiness, and the pigs in the streets. So there are plenty of people who just see the dark side. What I love about Whitman is that this man sees beauty in that. He sees the Mississippi in Broadway. He sees identity in the city.

Walt Whitman (as portrayed by actor): Here are people of all classes and stages of rank — from all countries of the globe, every hue of ignorance and learning, morality and vice, wealth and want, fashion and coarseness, breeding and brutality, elevation and degradation, impudence and modesty.

Ed Folsom: Whitman feels the power of the city of strangers. He's looking at a city of strangers and how something we might now call urban affection begins to develop. How do you come to care for people that you have never seen before and that you may never see again? Every day we encounter people, eyes make contact, we brush by people, physically come into contact with them, and may never see them again. But Whitman's notebooks at this time are filled with images, just jottings, of these people, what they're doing, what they look like, what their names are. 'What is this person doing? What's the activity that defines this person? If I were doing that activity that person would be me. If I were wandering the other way, rather than this way, that person could be me. That could be me. That could be me. What is it that separates any of us?'

Narrator: By 1847, within a few years of his arrival in New York, Whitman's parents and siblings had moved into nearby Brooklyn, where they tried to cash in on the new building boom — and failed. Walt was drawn back into the family home to help with the finances, and to bear the weight of his father's final slide into defeat and bitter resignation.

Kenneth Price, scholar: He took on a parental role in the family. I think as early as 1847 he held the title to the family home even though his father would live until 1855. He's clearly the one they all turn to as the smart one, the one with insight, the person who's emotionally stable.

Narrator: Despite their downward mobility, the Whitmans felt themselves tied to a bigger destiny. Whatever their station, New Yorkers were apt to see their city as the ornament of the nation — a nation that bestrode a continent. Walt could leave his troubled home, go to the office and editorialize the glory of the U.S. victory in the Mexican War, which landed Americans half a million square miles, including California, Texas and territory enough for a slew of other states. But the new acquisition raised again — and for good — an issue on which the nation was hopelessly split. In 1848, Walt Whitman had no particular concern for the emancipation or the welfare of black slaves. And he could not abide fanatical abolitionists who were willing to pull the Union apart if Southern states refused to renounce slavery. Whitman was chiefly worried that the white working class would have to compete with slave labor in the new western territories, as they did all over the South.

Walt Whitman (as portrayed by actor): In fifteen of The States three hundred and fifty thousand masters of slaves keep down the true people, the millions of white citizens: mechanics, farmers, boatmen, manufacturers, and the like.

Narrator: Whitman's fierce and full-throated cry for the working man got him fired again, but a publisher offered the editorship of a new paper: the Crescent. There was one catch — the job was in New Orleans.

Ed Folsom: And Whitman takes him up on it. It's a chance to see the nation in a way that he has not at all. He hasn't really been out of a very narrow confine of New York and, and Long Island. And so this is going to be for Whitman the big trip. This is going to be Whitman's equivalent to the trip to Europe that the children of the privilege classes took.

Narrator: Early in 1848, 28-year-old Walt Whitman and his teen-aged brother, Jeff, steamed out of a gray-wrapped New York winter and into the mellow weathers of the Deep South. Peach trees were already in full blossom when the brothers arrived in New Orleans. The scent of magnolia, myrtle, and bougainvillea perfumed the city squares. Whitman had duties at the newspaper, but he was seduced by the sensual public life of New Orleans. He watched the shirtless dockworkers at the wharves and the semi-nude actors and actresses enacting scenes from the bible. Or sat for hours amid the soft-voiced social whirl of the open-air bars, where locals spoke a gumbo of English, French, Spanish, and Cajun. He was especially drawn to the young women selling roses and violets on the street.

Walt Whitman (as portrayed by actor): Women with splendid bodies — no bustles, no corsets, no enormities of any sort: large, luminous eyes, faces a rich olive, fascinating, magnetic, sexual, ignorant, illiterate; always more than pretty. Pretty is too weak a word to apply to them."

Yusef Komunyakaa, poet: There is, you know, the myth of him actually having a relationship with a black woman or a black man.

Ed Folsom: He sees racial mixture and cultural mixture in New Orleans on a scale that he has not encountered before and sees that it can work. It can be exciting. It can be exhilarating. It can lead to an intense new kind of affection. Because I think part of that urban affection in Whitman is always that, that sense of, of violation, a sense of crossing a barrier and discovering you can cross it and not be harmed by it but in fact be strengthened by it, enlarged by it.

Narrator: There was another, more difficult crossing the trip South forced on Whitman — a crossing that would haunt him for years. In New York, where slavery had long been illegal, Whitman had easily averted his gaze from the true costs of the institution. But in New Orleans, he came face to face with the stark fact of human bondage in a country founded on the idea of freedom, face to face with an entire race of people excluded by law and by force from the American story.

Ed Folsom: He sees slave auctions take place. And as he sees bodies of human beings for sale he is stunned by the brutality and the sheer physical force of the experience.

Betsy Erkkila: He would have seen auctioneers enumerating literally body parts in selling human beings as commodities. And buyers would actually feel slave's bodies in trying to figure out if they were going to buy them.

Yusef Komunyakaa: For some reason I feel like he has the capacity to imagine himself on the auction block as well.

Ed Folsom: That could be me. That could be me. That person could be me.

Yusef Komunyakaa: It really enters his psyche. I think he's wrestling with himself.

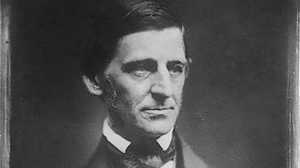

Narrator: When Walt returned to his parents' home in Brooklyn after just three months in New Orleans, he carried with him a poster advertising a slave auction, and vague premonitions that the contradictions in American democracy would prove fatal. Over the next eight years, the issue of slavery festered: by 1855, an armed battle had already commenced on the Kansas-Missouri border. Rickety compromise legislation in Washington crumbled. The bonds of national affection were being eaten away. And Whitman could see that the nation's political leaders were too timid or too self-interested to minister to the sickness before it rotted America to the bone. What the nation needed, Whitman was convinced, was a call to healing from a voice that was of, by, and for the common people. "The poet is representative," America's literary eminence, Ralph Waldo Emerson, had essayed ten years earlier. "He stands among partial men for the complete man. The poet is the man without impediment, who sees and handles that which others dream of, traverses the whole scale of experience. I look in vain for the poet I describe."

Allan Gurganus: I think Walt Whitman went to the help wanted section and found a squib that said "Wanted: National Poet." And he was innocent enough to believe there really was such a job. And if he could just write a poem that incorporated everything he felt and suspected and hoped for from America that he would have the position.

Narrator: Alone in the garret of a working class house in Brooklyn, New York == jotting in a three-and-a-half by five-and-a-half inch notebook == Walt Whitman searched for a poetic voice that could gather up and bind all the disparate places and people of America, a voice that would rise above despair and cynicism and intolerance to sing the vast promise of the country.

Ed Folsom: As you read through his little notebook you can see the moment where Leaves of Grass begins to emerge. In typical Whitman fashion there all kinds of things in this notebook: little notations of what he owes people and he's got addresses and names of people and places that he has to go. And then he begins writing in prose. And what he's writing are ideas. He starts out saying, 'be simple and clear, be not occult.' He's looking for his voice. And at one point he says 'every soul has its own individual voice.' And then he has a line that I've always been fascinated with, it says, 'do not descend among professors and capitalists.' And he stops at that point and there a couple of blank pages. And then when you turn the page suddenly there it is. And it starts, 'I am the poet of slaves and of the masters of slaves. I am the poet of the body and I am ... ' and then he stops. And in that moment where he writes 'and I am' I can feel the moment where Whitman senses that "I" that is going to become his main character in all of his poems. That "I" has come into existence. 'And I am.' And then he crosses those little lines out. And there's a little space. And then he writes the first lines that are going to get into Leaves of Grass. 'I am the poet of the body and I am the poet of the soul. I go with the slaves of the earth equally with the masters. And I will stand between the master and the slaves, entering into both so that both will understand me alike.' And there it is. Everything that's going to be great in Whitman is in those lines.

Narrator: Out of that small notebook grew a thin volume with twelve untitled poems, type-set by the hand of the poet himself.

Martin Espada, poet: I celebrate myself, And what I assume, you shall assume

Yusef Komunyakaa: For every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you. I loafe and invite my soul,

Allan Gurganus: I loafe and invite my soul, I lean and loafe at my ease, observing a spear of summer grass.

Walt Whitman (as portrayed by actor): The spotted hawk swoops by and accuses me. He complains of my gab and my loitering. I too am not a bit tamed. I too am untranslatable, I sound my barbaric yawp over the roofs of the world.

Martin Espada: I speak the password primeval. I give the sign of democracy; By God! I will accept nothing which all cannot have their counterpart of on the same terms. Through me forbidden voices, Voices of sexes and lusts. Voices veiled, and I remove the veil, Voices indecent by me clarified And transfigured.

Billy Collins, poet: Here was the first truly American poet who broke out of the form of formal poetry. You know how in a sonnet you have these boundaries. Leaves of Grass is a poem without boundaries and so that everything can flood into it: People, professions, landscape, memories, engineering, water, children, Native Americans. There's no boundaries keeping anything out.

Narrator: Leaves of Grass contained astronomy, mythology, Egyptology, religions of the East and West, and the latest science. The sublime operatic line and the blunt, coarse talk of the Five Points were in Leaves. The carpenter, the printer, the half-breed, patriarchs, prostitutes, opium eaters, and the President himself peopled the poems; the squaw in her yellow-hemmed cloth was there on the page, the bride in her white dress, Kentuckian, Georgian and Californian. What joined them to one another was the firm embrace of Poet himself — who was, after all, just one of the crowd.

Ed Folsom: Whitman portrays himself on the title page in the frontispiece without his name, but with an image of himself unlike any image of a poet before. It's not the poet from the shoulders up dressed in formal dress which emphasizes the poetry that comes from the intellect, the poetry that comes from a life of privilege and education. Instead, this is poetry that comes from a life of walking in the streets. It's the poetry that emerges through the hands and arms and through the heart pumping blood to all parts of the body. The perspiration, the aroma of these arm pits Whitman talks about — aroma finer than prayer.

Kenneth Price: This was everything about sinews. This was everything about crotch. This was everything about armpits. For him you couldn't have an honest poetry that wasn't including the whole person.

Karen Karbiener: Nakedness from the first page is celebrated. Whitman's openness and celebration of sexuality and not just heterosexual sex but sex on the edges, masturbation, voyeurism, oral sex, it's in there.

Allan Gurganus: I grew up in Rocky Mountain, North Carolina. There was not a working bookshop but there was a stationery department in the corner of the best department store. And there among the greeting cards were a few books including Leaves of Grass. I had somehow heard through the ten-year-old grapevine that it had some hot stuff in it. I bought it assuming that the clerk would believe that it was for inspirational purposes and pedaled to the nearest woods. And I opened and began looking for the good parts and discovered that in a strange way it's all good parts in Whitman; that you're never more than four lines from an erotic jot. There, you're never very far away from the body.

Walt Whitman (as portrayed by actor): I mind how we lay in June, such a transparent summer morning; You settled your head athwart my hips and gently turned over upon me, And parted the shirt from my bosom-bone, and plunged your tongue to my barestript heart, And reached till you felt my beard, and reached till you held my feet. Swiftly arose and spread around me the peace and joy and knowledge that pass all the art and argument of the earth; And I know that the hand of God is the elderhand of my own.

Yusef Komunyakaa: There's a whole thing about the sexuality and all. But I think maybe there is a kind of deeper more serious taboo.

Ed Folsom: Whitman equates the human body and democracy in some radical and essential way: that the human body is what we all share. We all experience this world through the body. And if we can all begin to agree that the body itself is a sacred thing then we have the beginnings of democracy.

Yusef Komunyakaa: A slave at auction! I help the auctioneer. The sloven does not half know his business. Gentlemen look on this curious creature, Whatever the bids of the bidders they cannot be high enough for him, For him the globe lay preparing quintillions of years without one animal or plant, For him the revolving cycles truly and steadily rolled. In that head the all baffling brain, In it and below it the makings of attributes of heroes. Examine these limbs, red, black or white. They are very cunning in tendon and nerve. They shall be stripped that you may see them. Exquisite senses, life lit eyes pluck volition and wonders within there yet. Within there runs his blood. The same old blood. The same red running blood.

Narrator: Walt could afford to print only 795 copies of his ungainly, oversized first edition. A few hundred he bound in dark green cloth, the rest in paper. He found a few stores willing to stock the book, set a price, and loosed it on the world.

Karen Karbiener: There were some writers that really supported that vision. But there were so many bad reviews. And many of them came from prestigious voices of the day.

Kenneth Price: One or more reviewer will suggest that he be whipped in the streets. And that one suggests that he should commit suicide.

David Reynolds: Another reviewer said that this author must be like a lunatic, an escaped lunatic, raving in pitiable delirium.

Kenneth Price: Other people describe Leaves of Grass as being like an explosion in a sewer. And so, so people go to great lengths to really say some brutal things about his book.

Narrator: Whitman was oddly cheered by the reaction of the literary elite. He liked that they seemed so obviously threatened by his homemade book. In fact, the force and volume of the denunciation of Leaves of Grass only increased Whitman's already high hopes.

Kenneth Price: Whitman had a remarkable faith in ordinary people to understand his book. It's celebrating American democracy. It's talking the language of the people. It's attacking aristocratic influences in American life. Why wouldn't this be very, very popular with the people? He expected stage drivers to stop between runs and pull out a copy of Leaves of Grass. People going out to plow the fields have a copy of Leaves of Grass in their very large back pocket to accommodate that, that huge book.

David Reynolds: In the preface to this book he had written, 'this is what you shall do. You shall take my volume every month out in nature and you'll read it under the sky.' And he expected people to be healed. And he expected America to kind of come together in this vision, this poetic vision.

Narrator: Walt's poetic vision did not exactly sweep the nation. A dozen people bought the book, maybe two-dozen. Whitman gave away more than he sold. His own family showed little interest. "I saw the book," said Walt's brother George. "Didn't read it at all == didn't think it worth reading." The one glimmer of hope came from the high arbiter of literary America == Ralph Waldo Emerson, to whom Whitman had sent one of the first copies of Leaves of Grass. Emerson's actual response was markedly ambivalent. He wrote to friends that Leaves was "a nondescript monster," with "terrible eyes and buffalo strength, American to the bone." He wasn't convinced the book could properly be called poetry but Emerson also recognized that Leaves of Grass could not be ignored, that its author merited encouragement.

Betsy Erkkila: And Emerson, who was the God in some ways of American letters, took the time out to write Whitman an extraordinary letter in which he basically says that he rubbed his eyes a little bit to see if this was no dream.

Narrator: "I find it the most extraordinary piece of wit and wisdom that America has yet contributed," Emerson wrote. "I give you joy of your free and brave thought. I have great joy in it. I find incomparable things said incomparably well, as they must be. I greet you at the beginning of a great career."

Allan Gurganus: There are very few people in our culture who would be a concomitant figure to Emerson then. It's a combination of Billy Graham and Oprah Winfrey. It's so powerful to imagine that Whitman told nobody he had received this letter. He walked around with it in his breast pocket probably walking out into fields and meadows which were still then available in Brooklyn reading and reading and rereading it.

Narrator: Whitman understood the letter was meant for his eyes only. Ralph Waldo Emerson was a jealous guardian of his own standing, careful about whom he anointed in public. But Whitman's grand project was hanging by a thread. Leaves of Grass was too dear to Walt == and too important to the nation he loved == to adhere to the niceties of social intercourse.

David Reynolds: He actually had the letter printed in the New York Tribune which a little, little suspect there. And without Emerson's permission.

Narrator: Whitman didn't stop there. With sales sill lagging, he wrote at least three anonymous and bombastic reviews of Leaves of Grass. "He is to prove either the most lamentable of failures or the most glorious of triumphs in the known history of literature," Whitman wrote of himself. "Here we have a book which fairly staggers us . . . An American bard at last!" For all his manic effort, sales of Leaves did not improve. So Whitman simply bent to work on his next hope == a second edition == preparing twenty new poems and revising the original twelve. He was desperate to connect.

Ed Folsom: Whitman publishes a new poem called Sun-down Poem in this edition eventually called Crossing Brooklyn Ferry. He writes: "It avails not neither time or place. Distance avails not. I am with you, you men and women of a generation or ever so many generations hence. I project myself. Also I return. I am with you and know how it is." Whitman places his "I," the "I" that's been speaking in the present tense, puts it into the past. And he puts himself in a past now that's so far past that he's not alive anymore. And gives over the present tense of the poem to you and me, to us, the readers. Whitman in 1856 was not only imagining us in 2008 reading this poem, but projecting us into 2008 to read this poem. It's as if he is creating us as a character in the poem.

Ed Folsom: Just as you feel when you look on the river and sky so I felt. Just as any of you is one of a living crowd I was one of a crowd.

Walt Whitman (as portrayed by actor): Just as you are refreshed by the gladness of the river, and the bright flow, I was refreshed. Just as you stand and lean on the rail, yet hurry with the swift current, I stood, yet was hurried.

Martin Espada: My Brooklyn wasn't quite the Brooklyn of Walt Whitman. At the same time, there's so much I recognize in this. I certainly recognize in Whitman's deep appreciation for the fact that being alive my own appreciation for the fact of being alive. And he's absolutely right. I see his Brooklyn. And strangely enough, I think he saw my Brooklyn. As different as it was there were certainly things in common. I think about those seagulls. I saw those seagulls too. And damn, I think they're the same seagulls.

Walt Whitman (as portrayed by actor): Closer yet I approach you, What thought you have of me, I had as much of you — I laid in my stores in advance, I considered long and seriously of you before you were born. Who was to know what should come home to me? Who knows but I am enjoying this? Who knows but I am as good as looking at you now, for all you cannot see me?

Ed Folsom: What all the preaching in the world, what all the religions in the world have been telling you to have faith about: that there is some sort of life after death, that it's possible to communicate across time and across space. We've just proved it, haven't we? That we can talk beyond death. That we can have affection for one another beyond death.

Walt Whitman (as portrayed by actor): We understand, then, do we not? What I promised without mentioning it, have you not accepted? What the study could not teach—what the preaching could not accomplish is accomplished, is it not?

Narrator: Within weeks of the publication of the second edition of Leaves of Grass, two envoys from Emerson's world — writers Henry David Thoreau and Bronson Alcott — made pilgrimage to Brooklyn to have a look at this Walt Whitman. And Whitman put on a show. He invited the men up to his unkempt attic room where he made what he called his "pomes" at a rude wooden table. Thoreau, the man who had lived for seasons in Walden Woods, was taken aback by Whitman's unmade bed — a slop jar visible underneath. Alcott noted with a start the prints of Hercules, Bacchus and a satyr tacked to the attic wall, while Whitman bragged about bathing naked in Coney Island's winter surf. Walt Whitman was "broad-shouldered, rouge-fleshed, Bacchus-browed, bearded like a satyr, and rank." wrote Alcott. "Eyes gray, unimaginative, cautious yet sagacious; his voice deep, sharp, tender sometimes and almost melting. When talking he will recline upon the couch at length, pillowing his head upon his bended arm, and informing you naively how lazy he is, and slow." Whitman's strange pose — as always — was meant to deflect. He was the poet of health and glad tidings and he didn't care to let anybody see beyond that. In fact, Whitman himself was a master at denying the uglier facts at hand.

Allan Gurganus: He's loaded into a house with many, many siblings many of whom have pathologies which would fill the hour. He shared the bed with his profoundly retarded brother who over ate until he passed out from ingesting food.

David Reynolds: His brother Andrew became an alcoholic and was married to a woman who became a streetwalker. His sister Hannah was probably psychotic. She was very mentally unstable. His older brother, Jesse, Walt eventually had to commit him to the Kings County Lunatic Asylum.

Allan Gurganus: The more you read about Whitman's family life, the more you understand why he would prefer to be riding to and fro on horse drawn buses to and fro up and down Broadway again and again. He had to stay away from home as much as possible.

Narrator: In the late 1850s Walt liked to jump off the omnibus at Broadway and Bleecker, where he could descend among the revelers at an underground saloon called Pfaff's.

Allan Gurganus: Pfaff's was the Andy Warhol factory, the Studio 54, the Algonquin Round Table all rolled into one.

Karen Karbiener: It's a place where a lot of the theatrical set winds up. He's meeting cross dressers and all sorts of other edgy types. It's Bohemia for Whitman. And he realizes he kind of fits in there. He starts wearing these pants called "bloomers," which were the first pants that women actually wore. And they were kind of like pantaloons, very fluffy. But Whitman kind of wore them flamboyantly and tucked them in his boots and, you know, basically wore women's pants.

Allan Gurganus: Additionally, Pfaff's was a place to pick up beautiful young men. And it's very funny in reading some of the earlier history of Pfaff's the heterosexual white guys who are writing seemed always to wonder why would he go to Pfaff's so often? Duh, I can tell you why. It was where all the other outlaws gathered.

Walt Whitman (as portrayed by actor): One flitting glimpse, caught through an interstice, Of a youth who loves me and whom I love, silently approaching and seating himself near, that he may hold me by the hand. And long while, amid the noises of coming and going, there we two, content, happy in being together, speaking a little, perhaps not a word.

Allan Gurganus: Of all the young men he met at Pfaff's, Fred Vaughn, an Irishman, was the person that he felt closest to. In the two or three years Whitman lived away from home, Fred Vaughn was his roommate, was his pal.

Walt Whitman (as portrayed by actor): And that night, while all was still, I heard the waters roll, slowly, continually, up the shores I heard the hissing rustle of the liquid and sands as directed to me, whispering, to congratulate me, For the one I love most lay sleeping by me under the same cover in the cool night, In the stillness, in the autumn moonbeams, his face was inclined toward me, And his arm lay lightly around my breast — and that night I was happy.

Walt Whitman (as portrayed by actor): Take notice, land of the prairies, land of the south savannas, Ohio's land, Take notice, you Kanuck woods — and you Lake Huron — and all that with you roll toward Niagra — That you each and all find somebody else to be your singer of songs One who loves me is jealous of me, and withdraws me from all but love, With the rest I dispense — I sever from what I thought would suffice me, for it does not — I am indifferent to my own songs — I will go with him I love, It is to be enough for us that we are together — We never separate again.

Allan Gurganus: Just when Whitman felt closest to him, just when Whitman was literally willing to give up his mission as the great American poet — imagine he'd already published Leaves of Grass. This kid must have had something extraordinary — Mr. Vaughn decided that he wanted a wife and kids. He wanted a regular life. He was tired of lying to his family. And he moved out. He said good-bye.

Walt Whitman (as portrayed by actor): Hours continuing long sore and heavy hearted. Hours of the dusk when I withdrew to a lonesome and unfrequented spot. Seating myself. Leaning my face in my hands. Hours sleepless. Deep in the night, when I go forth, speeding swiftly the country roads or through the city streets. Or pacing miles and miles, stifling plaintive cries.

Allan Gurganus: These are passages in Whitman's life that don't make you feel embarrassed for him. They make you feel closer to him. Because anybody who hasn't experienced desertion and heartache is scarcely alive. And all you can say, in reading those poems, is that this was one of the great loves his life. We don't have images of Fred Vaughan. We don't know much about him. But the residue in the poems, the great chasm in the poems, make the poetry some of the most powerful that he ever wrote.

Allan Gurganus: Sullen and suffering hours! (I am ashamed — but it is useless — I am what I am;) Hours of my torment — I wonder if other men ever have the like, out of the like feelings? Is there even one other like me — distracted — his friend, his lover, lost to him? Does he see himself reflected in me? In these hours, does he see the face of his hours reflected?

Narrator: More than three years had passed since the publication of the second edition of Leaves, but in the aftermath of the Fred Vaughan affair, Walt had something he felt compelled to share with his countrymen — a simple new human equation for national healing. "Affection," he wrote, "shall solve every one of the problems of freedom." In January of 1860 — while southern States talked of abandoning the Union — Whitman let it be known that he was in search of a publisher, and a Boston firm called Thayer & Eldridge wrote to say that they wanted to publish the third edition of Leaves of Grass. "We can and will sell a large number of copies, try us. We can do good for you." Whitman's old swagger returned. "I feel as if things had taken a turn with me at last," Walt wrote to his brother Jeff. In Boston, preparing the new edition and its 124 new poems, Whitman made sure to be seen. "I create a sensation at Washington Street," he crowed. "Everybody here is so like everybody else. And I am Walt Whitman." When the great man himself, Emerson, took Walt for a walk in a Boston park and suggested he tone down the more explicit sexual references, Walt would have none of it. "The dirtiest book in all the world," he would later say, "is the expurgated book."

Karen Karbiener: The 1860 edition has two new clusters as he called them, the Calamus cluster and the Children of Adam cluster. Children of Adam, like the title says, has a lot to do with heterosexual love, procreation is really a featured element of a lot of the poems. But the Calamus poems, man, that is where the energy is.

Billy Collins: Passing stranger, you do not know how longingly I look upon you.

Yusef Komunyakaa: You must be he I was seeking or she I was seeking. It comes to be as of a dream. You give me the pleasure of your eyes, face, flesh as we pass, You take of my beard, breast, hands, in return,

Martin Espada: I am not to speak to you. I am to think of you when I sit alone or wake at night. Alone. I am to wait. I do not doubt I am to meet you again. I am to see to it that I do not lose you.

Ed Folsom: I think that Whitman believed that Leaves of Grass was going to prevent a Civil War. I think he had that much faith in the 1860 Leaves of Grass. Leaves of Grass is really a book about preserving the Union. It's a book about holding things together, being able to absorb contradictions and still maintain a single identity. As the war begins, as Whitman sees it turn from what everyone thought would be a two week series of skirmishes into a brutal and long-lasting war he begins to believe that Leaves of Grass is a failure, is over.

Narrator: As the signal national event of his lifetime unfolded, Walt Whitman turned from it, and from poetry. For the first eighteen months of the American Civil War, he fell into a deep malaise. He busied himself with a sentimental history of old Brooklyn, and occasionally picked fights at Pfaff's. His connection to the war was his brother George, who was fighting with the 51st New York. Walt followed the 51st in the newspapers, through its battles at Roanoke Island, Kelly's Ford, Second Bull Run, Antietam, and then at Fredericksburg, Virginia, where on December 13, 1862, the Union's commanding general had ordered fourteen futile attacks against fortified Rebel position. When George's name appeared in the casualty lists in the New York newspapers just before Christmas of 1862, Walt headed to the front to find his brother.

Ed Folsom: Whitman comes to Fredericksburg not knowing what he's going to find and walks by the mansion that has been turned into the hospital. And what he recalls seeing is a pile of severed limbs, amputated limbs, arms and legs of the soldiers. And this war becomes for him a war on the body as well as a war between the states.

Narrator George Whitman was alive and well, but Walt remained in Fredericksburg for more than a week — drawing nearer the war each day. In his small green notebook, Whitman began recording the sights, the sounds and the smells of the camp — and the soldier language of the front. He walked the charred and denuded landscape of the now-still battlefield, watched the silent burial teams at work, pulled back the army-issue blankets to look on faces of the dead, and visited with the men who would soon enough be dead.

Walt Whitman (as portrayed by actor): I do not see that I do much good to these wounded and dying; but I cannot leave them. Once in a while some youngster holds on to me convulsively, and I do what I can for him; at any rate stop with him and sit near him for hours, if he wishes it.

Narrator: Doctors in the field hospital noticed Whitman, and asked him to tend to a trainload of casualties headed north to the capitol, when a few of the wounded on that train asked the favor of his company at the hospitals in Washington, Walt could not refuse. The hospitals Whitman entered were a primitive business. Surgeons sharpened knives on their boot soles. "We knew nothing about antiseptics," wrote one doctor, "and therefore used none." Infection cut through those wards. Gangrene cases had to watch as their tissue was eaten away. The smell was so bad they were often isolated and left to die alone.

Walt Whitman (as portrayed by actor): You hear groans or other sounds of unendurable suffering from two or three cots, but in the main there is quiet. Most of these sick or hurt are entirely without friend or acquaintances here. In one of the hospitals I find Thomas Haley, shot through the lungs — inevitably dying. The poor fellow is like a frightened animal.

Narrator: "What was a man to do?" Walt would later write. "There were thousands, tens of thousands, hundreds of thousands needing me."

Karen Karbiener: He gives up everything, drops it and he volunteers over the next three, four years in these horrific hospitals where amputation is considered a solution.

Allan Gurganus: He found a job as a copyist which essentially was like a typist of the day. He would work until noon. Then he would go to the wards from noon until four. At four he would go back to the O'Connor's House. He would take a bath. He would refresh himself, probably take a nap. Have a supper. And then, at six, he would return to the ward and stay from six to nine. If a particular soldier was particularly wounded and particularly wanted his company he would stay the night at the hospital and go directly from the ward to work the next morning.

Narrator: In the spring of 1863 Whitman made his rounds from his small apartment to his government office building to the forty hospitals in and around Washington, roaming through a nervous city. Uniformed soldiers peopled the streets, and bunked down in the Capitol, or in the park next to the Washington Monument, whose construction had stalled at a squat 152 feet. Completion was no sure thing. News of General Lee's victory over the Union forces at Chancellorsville echoed through the capital city. The Rebels were at the gates for all anyone knew.

Walt Whitman (as portrayed by actor: The squad of the guard patrolling about examining passes, a sentry at the door, a cavalry man on horseback with naked sabre over his shoulder, like a statue at the corner. A great white Aladdin's palace, with an unfinished dome (reported to be cracking), the Goddess of Liberty meanwhile standing in the mud waiting. The light falls, falls, touches the cold white of the great public edifices — touches with a kind of death-glaze here and there the windows of Washington.

Narration: This awful scene, Whitman had come to believe, was beyond a poet's healing — certainly beyond his healing. Walt had no plans to make new editions of Leaves of Grass. He had dedicated himself to his duty in the hospitals. That was all he had to give. What hope he still had for the continuation of America's grand democratic experiment, he grafted onto a new savior. "I see the President almost every day," he wrote, "we have got to where we exchange bows, and very cordial ones. I never see the man without feeling that he is one to become personally attached to."

David Reynolds: Lincoln embodied everything that the I, the first person, of Leaves of Grass was meant to embody. He was the average, ordinary, every day American. And yet he was gifted with such eloquence. He had a kind of poetic side to him.

Karen Karbiener: Apparently he used to wait in front of the White House while he was working in D.C. just for a glimpse of his Redeemer president, as he called him. He used to say things like I remember a quote that Lincoln was so ugly he was beautiful you know. It went back around for him. There was something so appealing about this homely man.

Narrator: Walt may have recognized something of himself in the stooped shoulders and sad eyes of the besieged and unpopular President. In 1863, Lincoln was under attack for instituting the first federal income tax and a military draft == and for signing the controversial Emancipation Proclamation, freeing the slaves in any state in rebellion. Whitman backed him on all of it. Above all, Walt honored Lincoln's vow to save the Union, even as the terrible cost of the President's stubborn will grew. After every big battle near Washington, hundreds of wounded a day debarked at the foot of Sixth Street == more than a thousand some days. "The war," Whitman wrote, "seems to me like a great slaughter-house and the men mutually butchering each other."

Walt Whitman (as portrayed by actor): When I am present at the most appalling scenes, deaths, operations, sickening wounds (perhaps full of maggots,) I do not give out or budge. But often, hours afterward, perhaps when I am home, or out walking alone, I feel sick, and actually tremble. Yesterday was the worst, many with bad and bloody wounds, inevitably long neglected. The sight of some cases brought tears to my eyes. I had the luck yesterday, however, to do some good.

Ed Folsom: He would get dressed up and, and, and wash his beard and all the young soldiers would call him old man, even though he was only 40-some years old at the time, because he really did look as one soldier said as Santa Claus coming through the wards and he was carrying his little bag and he would give them candy and he would give them treats and he would he would take down their, their requests for, for small things that he would go and get.

Allan Gurganus: His bag contained tobacco aplenty. And like a good mother no child ever got more than the other child. He would have notepaper. He would have jelly. He would have pens. He would have pickles. He would have biscuits. Any treat that a soldier could have imagined. There was a moment when he gave fifteen cents to one of these boys and the boy said, 'I'm going to buy milk from the milk lady.' And then burst into tears.

Ed Folsom: The intensity of that sense of encountering the strangers again and feeling tremendous affection for them, demonstrating that affection. Many of the soldiers as they were dying the last kiss they would have, the last moment of affection they would have would be from this bearded poet who had taken time to stop with them. There were these again moments of what he had learned in New York to be those moments of urban affection. That in the hospital became national affection — all of these soldiers from all over the country, southern soldiers as well as northern soldiers. There really was a sense in those hospital wards of Whitman encountering the country, the entire nation in a way that he never would in any other form in any other setting. They were all there and he would absorb it all, show affection for them all.

Walt Whitman (as portrayed by actor: I have spent a long time with Oscar F. Wilber, Company G, 154th, New York, low with chronic diarrhea and a bad wound also. He talked of death, and said he did not fear it. He behaved very manly and affectionate. The kiss I gave him as I was leaving he return'd fourfold. He died a few days after.

Narrator: Whitman's efforts in the hospitals — 600 visits he figured, to more than 100,000 patients — left him near collapse. He suffered from insomnia, night sweats, night terrors, headaches, sore throat and buzzing in the ears. Alone with his ailments, in a spartan third-floor walk-up ten blocks from the White House, Walt Whitman found strength enough to extend one final and solemn service to the soldiers he'd come to know so well. He opened his notebooks and began sketching his memorial to them all, in a new book of poetry he called Drum-Taps.

Martin Espada: From the stump of the arm, the amputated hand, I undo the clotted lint. Remove the slough. Wash off the matter and blood. Back on his pillow the soldier bends with curved neck and side falling head. His eyes are closed. His face is pale. He dares not look on the bloody stump and has not yet looked on it. I am faithful. I do not give out. The fractured thigh, the knee, the wound in the abdomen, these and more I dress with impassive hand. Yet deep in my breast a fire, a burning flame. Thus in silence in dreams' projections, Returning, resuming, I thread my way through the hospitals, The hurt and wounded I pacify with soothing hand, I sit by the restless all the dark night, some are so young, Some suffer so much.

Narrator: Walt Whitman completed the manuscript for Drum-Taps around the time of Lincoln's second inauguration. A month later Lee surrendered his Army at Appomattox and the bloody fighting was over. Whitman's hero President had saved the Union — and the poet was convinced Abraham Lincoln could repair the national breach. Five days after the surrender — on Good Friday — Walt was back home in Brooklyn with his family. George was finally home too, after four years at war. Jeff was prospering. Drum-Taps was ready for the printer. An early bloom of daffodils, hyacinths and tulips scented Portland Avenue. And there, at his mother's house, Whitman received news of the last sad casualty of the long war.

David Reynolds: Southerners as well as Northerners were stunned and were on some level grieved by the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. So Lincoln becomes in death in a sense a greater version of what he had been in life.

Billy Collins: Coffin that passes through lanes and streets, Through day and night, with the great cloud darkening the land, With the pomp of the inloop'd flags, with the cities draped in black, With the show of the States themselves, as of crape-veil'd women, standing, With processions long and winding, and the flambeaus of the night, With the countless torches lit-with the silent sea of faces, and the unbared heads,

David Reynolds: Walt Whitman, who above all had been searching for unity, comradeship, togetherness, feels that in the death of Abraham Lincoln we finally have that kind of unity that America had lacked before that. The unity that is finally achieved and that Whitman's early poetry could, couldn't, tried to achieve but never could.

Walt Whitman (as portrayed by actor): Then there is a cement to the whole people, subtle, more underlying, than any thing in written constitution, or courts, or armies. Namely, the cement of a death identified thoroughly with that people, at its head, and for its sake. Strange (is it not?) that battles, martyrs, agonies, blood, even assassination, should so condense, perhaps only really, lastingly condense, a Nationality.

Ed Folsom: It's only going to be after the Civil War that he is going to begin to re-conceive and re-imagine Leaves of Grass so radically that after the Civil War he would actually say at one point that the Civil War is the very heart and the center of Leaves of Grass around which the book works. In the 1867 edition he actually sews in, I think of it as an act of suturing, a kind of wartime act or just post wartime act of suturing Drum Taps, the Civil War poems, into the back of Leaves of Grass. And in that act he has made the decision that Leaves of Grass is large enough, absorptive enough, broad enough to absorb this national disaster and what new life now for America now can possibly grow out of it.

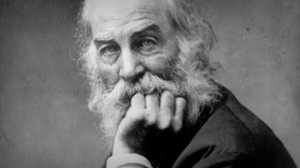

(On-screen text): Camden, NJ, 1884

Narrator: The war completed Leaves of Grass and put a period on an era. Walt Whitman spent many of the following 25 years confined to a small house he bought in Camden, New Jersey, while the country the poet had so lovingly absorbed faded from view. Post-war America eluded Whitman's grasp; what grew from the Civil War disappointed. Whitman added little to Leaves of Grass in the long years after the War. He tinkered and edited, pulled some of the more revealing Calamus poems, attached small addenda. The aging poet suffered a series of strokes. His legs failed him. His lungs withered. Abscesses surrounded his heart. One growth eroded a rib, leaving him in excruciating pain. He had an enlarged prostate, a fatty liver and a gallstone.

Karen Karbiener: At the end of the 1880s he was wheelchair bound and really found one side of his body completely paralyzed. So this was a man on all fronts, you know, intellectual, political, personal saw some debilitating changes.

Walt Whitman (as portrayed by actor): Approaching, nearing, curious, thou dim uncertain specter — bringest thou life or death? Strength, weakness, blindness, more paralysis and heavier? Or placid skies and sun? Wilt stir the waters yet or haply cut me short for good? Or leave me here as now, Dull, parrot like and old, with crack'd voice harping, screeching?

Karen Karbiener: You have poems that are complaining about old age and about cricketiness. He even writes about his body's condition. You learn he's got diarrhea, you know. But to him that's important. He's putting his body on paper. But there's something else too. There's an idea that there's something beyond the body. It's as if he knows he's got to leave that shell behind, and yet there's something to look forward to also.

Walt Whitman (as portrayed by actor): Ah whispering, something again unseen Where late this heated day thou enterest at my window, Thou laving, tempering all, cool- freshing, gently vitalizing Me, old, alone sick, weak-down, melted, worn with sweat Thou, nestling, folding close and firm yet soft, Companion better than talk, book, art.

Martin Espada: What's striking to me is how he lets down his guard and how he honestly expresses himself as a, a sick, old man, grateful for a moment's breeze which may or may not be indicative of something out there in the universe.

Walt Whitman (as portrayed by actor): So sweet thy primitive taste to breathe within, Thy soothing fingers on my face and hands, Thou, messenger-magical strange bringer to body and spirit of me, (Distances balked — occult medicines penetrating me from head to foot) I feel the sky, the prairies vast — I feel the mighty northern lakes, I feel the ocean and the forest — somehow I feel the globe itself swift swimming in space; Thou blown from lips so loved, now gone Haply from endless store, God-sent, (For thou art spiritual, Godly) Minister to speak to me, here and now, what word has never told and cannot tell, Hast thou no soul? Can I not know, identify thee?

Narrator: Walt Whitman died in Camden, New Jersey, in 1892. His life's work, Leaves of Grass == which he had tended obsessively, for thirty-five years, through seven separate editions == had grown from 95 pages and twelve poems to 400 pages and more than 300 poems. No wife survived him, and no children; he left his most cherished possession, Leaves of Grass, to anyone who would have it.

Walt Whitman (as portrayed by actor: I depart as air. I shake my white locks at the runaway sun, I effuse my flesh in eddies and drift it in lacy jags. I bequeath myself to the dirt to grow from the grass I love, If you want me again look for me under your boot soles. You will hardly know who I am or what I mean, But I shall be good health to you nevertheless, And filter and fibre your blood. Failing to fetch me at first keep encouraged, Missing me one place search another. I stop somewhere waiting for you.

(On-screen text): Walt Whitman printed 795 copies of the first edition of Leaves of Grass in 1855. About two dozen sold.

(On-screen text): In 2008, millions of copies of Leaves of Grass are in circulation around the world.