Interviewer (re-creation): Come on in. Have a seat won't you? Thank you Sir... Let's roll sound. Roll camera. Sound speed. Speed. Mark.

Judge Kennedy, What is your opinion of Mr. Welles' radio play?

Judge A.G. Kennedy, Union, SC (Actor): Well, I certainly have an opinion. I think suit should be filed against him and the Columbia Broadcasting System for their wrongdoing. Welles' performance on the radio Sunday evening was a clear demonstration of his inhuman instincts and his fiendish joy in causing distress and suffering all over the country. He is a carbuncle on the rump of degenerate theatrical performers and he should make amends for his consummate act of asininity.

Narrator: Orson Welles' War of the Worlds.Never before had a radio broadcast provoked such outrage, or such chaos. Upwards of a million people convinced, if only briefly, that the United States was being laid waste by alien invaders, and a nation left to wonder how they possibly could've been so gullible.

Interviewer (re-creation): Please tell us, were you at all surprised by the reaction to the radio broadcast?

Besse P. Gephart, Clayton, Missouri (actor): I think the reaction was the most damning indictment of the stupidity of the masses.

E.M. Moody, Venice, California (actor): Now I appreciate what C.B.S. and Radio have done for the world. But why not respect that appreciation and not destroy all the faith and confidence we have in the greatest means of getting information about the world -- Radio.

Narrator: Brilliantly directed by Welles, The War of the Worlds would become, in the end, the most famous radio program in history -- known forever after as "the Panic Broadcast."

Yet it all began unremarkably at a little past 8:00 in the East -- a Sunday evening like any other in America, with dinners being finished, dishes washed, and radios across the country turned on more or less in unison.

Announcer, The War of the Worlds (archival audio): The Columbia Broadcasting System and its affiliated stations present Orson Welles and the Mercury Theater on the Air in The War of the Worldsby H.G. Wells. Ladies and gentlemen, the director of the Mercury Theater and the star of these broadcasts: Orson Welles.

Orson Welles, The War of the Worlds (archival audio): We know now that in the early years of the 20th century this world was being watched closely by intelligences greater than man's yet as mortal as his own. We know now that as human beings busied themselves...

Narrator: It was October 30th, the eve of Halloween -- a night known variously as Mischief Night, Devil's Night, Hell Night... a night that for some two hundred years had unleashed all manner of trickery on the unsuspecting. On this night, in 1938, it would also unleash the pent-up anxieties of a nation.

Interviewer (re-creation): Now Miss Hoadley. Can you describe the events that happened to you on the evening of the broadcast?

Esther L. Hoadley, Chicago, Illinois (Actor): Of course, yes. Well, returning that evening from a delightful Vesper service and a 62-cent dinner at Huylers, it was delicious, I changed into my housecoat and prepared to shorten my velvet skirt. Automatically I reached out and turned on the radio...

Radio commercial (archival audio): The makers of Chase and Sanborn Coffee, the superb blend you know is fresh present...

Narrator: Of the tens of millions of Americans listening to their radios at 8:00 that Sunday evening, few were tuned to The War of The Worlds. The big draw on the airwaves that night was a ventriloquist act: Edgar Bergen and his wooden dummy, Charlie McCarthy -- the improbable stars of NBC's hit variety show, The Chase and Sanborn Hour.

Charlie McCarthy, wooden dummy (archival audio): A haunting we will go, A haunting we will go.

Edgar Bergen, ventroliquist (archival audio): Hey Charlie, the word is hunting.

Charlie McCarthy, wooden dummy (archival audio): Well, not on Halloween it ain't.

Edgar Bergen, ventroliquist (archival audio): Thanks Charlie, but we'll let Nelson Eddy do the singing... And it's the rousing rip roaring song of the vagabonds from the vagabond king...

Narrator: But when the opening comedy routine gave way to a musical interlude, millions of listeners began twirling the dial.

Susan Douglas, Historian: There was something called dial twisting, the radio equivalent of channel surfing with the remote, so people turned the dial, and this is just when things are starting to heat up in the War of the Worlds broadcast. They missed the beginning, they missed the announcement that this was a play.

Announcer, The War of the Worlds (archival audio): Ladies and gentlemen, we interrupt our program of dance music to bring you a special bulletin from the Intercontinental Radio News. At 20 minutes before 8:00, central time, Professor Farrell of the Mount Jennings Observatory, Chicago, Illinois, reports observing several explosions of incandescent gas, occurring at regular intervals on the planet Mars. The spectrascope indicates the gas to be hydrogen and moving toward the earth at enormous velocity.

E.M. Moody, Venice, California (actor): So all of a sudden, a startling announcement, professor so and so from Princeton University had just observed several explosions on the planet Mars shooting out great jets of blue flame traveling at a rapid speed toward Earth.

Announcer, The War of the Worlds (archival audio): ...now nearer home comes a special bulletin from Trenton New Jersey. It is reported that at 8:50pm a huge, flaming object, believed to be a meteorite, fell on a farm in the neighborhood of Grovers Mill, New Jersey 22 miles from Trenton. We have dispatched commentator Carl Phillips to the scene...

E.M. Moody, Venice, California (actor): Then, suddenly another announcement, a news bulletin...

Frank Readick (Carl Philips, The War of the Worlds, archival audio): This is Carl Philips out at the Wilmuth Farm, Grovers Mill...

E.M. Moody, Venice, California (actor): …a farmer in Grovers Mill New Jersey had reported a meteor had fallen on his farm.

Interviewer (re-creation): And what did he say about it?

E.M. Moody, Venice, California (actor): He describes a hissing sound and a streak of greenish light that hit the earth with such force it knocked him from his chair.

John F. Powers, East Douglass, Massachusetts (actor): So I got the story just when the radio announcer was asking the fellow in New Jersey what it felt like seeing what happened in his back yard.

Frank Readick (Carl Phillips, The War of the Worlds, archival audio): Ladies and gentlemen, you've just heard Mr. Wilmuth, owner of the farm where this thing has fallen. I wish I could convey the atmosphere, the background of this fantastic scene. Hundreds of cars are parked in a field in back of us. Police are trying to rope off the roadway leading to the farm, but it's no use.

John F. Powers, East Douglass, Massachusetts (actor): The realism got me. I didn't know then it was a play, so I swallowed everything as it came over the air, like it was a new national emergency or something...

Narrator: By now, Americans were highly attuned to the sound of crisis. Nearly 10 years had passed since the economic collapse had pulled the rug out from under the country -- leaving millions stunned at their empty pockets and their bare cupboards and their new lives of ceaseless worry.

T.J. Jackson Lears, Historian: You have the stock market crash followed by mass unemployment, followed by horrendous bank failures, bank failures by the hundreds.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt, President (archival audio): Let me assert my firm belief that the only thing we have to fear is fear itself...

T.J. Jackson Lears, Historian: FDR recognized how terrified people were when the bottom dropped out.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt, President (archival audio) :...nameless, unreasoning, unjustified terror which paralyzes needed efforts to convert retreat into advance.

T.J. Jackson Lears, Historian: He brilliantly saw that the dominant mood of the country in the 1930s was not anger and not resentment at the capitalist system or at the bosses who had laid people off in record numbers but in fact was shame and fear, more especially fear.

Narrator: In the free fall of the Great Depression, radio had become a lifeline -- occupying pride of place in nearly 80 percent of American homes by 1938. Out-of-work Americans fell behind on the payments for their cars and their washing machines. They gave up their telephones. But they kept on buying radios by the millions.

Radio Bulletin (archival audio): ...we interrupt our normal schedule briefly to bring you a bulletin from the Press Radio Bureau. The death toll in the worst...

Narrator: In recent years, much of what had drifted through the ether and into their living rooms had been bad news...

Radio Bulletin (archival audio): ...the worst storm in years along the Eastern Seaboard has taken a death toll estimated at more than 200 lives. Untold damages...

Narrator: ...stories so unprecedented and unsettling they were nearly impossible to believe -- and yet they were true.

Radio Bulletin (archival audio): The sympathy of the world goes out to Colonel Lindbergh and his devoted wife in their supreme anguish at the kidnapping of their baby son Charles Augustus Lindbergh Jr.

Narrator: They had heard one eyewitness account after another...

Radio Bulletin (archival audio):: The United Press has tabulated 97 deaths in the 14 flood swept states. The President has already ordered all the federal agencies...

Narrator:...disaster after disaster, and then that terrible accident -- in May, 1937 -- when a German passenger airship, the Hindenburg, had been consumed by fire in New Jersey.

Herbert Morrison, reporter (archival audio): It's burst into flames! Get this Scotty. Get this Scotty. It's falling it's crashing, terrible! Oh my, Get out of the way please. It's burning and bursting into flames and the... and it's falling on the mooring mast. And all the folks agree that this is terrible; this is the one of the worst catastrophes in the world. Oh, it's crashing to the ground, oh the humanity and all the passengers...

Narrator: And all the while, in the background, had been the steady, ominous drumbeat of war.

Radio Bulletin (archival audio): President Roosevelt again appeals to Hitler to preserve peace. This bulletin is from The Press Radio...

T.J. Jackson Lears, Historian: Even worse, is what’s beginning to happen abroad, in the sense that we’re not only threatened from within our shores, we’re threatened from across the ocean too.

Newsreel (archival audio): In Germany, Adolf Hitler defies the Treaty of Versailles...

Narrator: For 18 days in September, 1938, the airwaves were dominated by news from Europe, as Hitler's threats to expand German territory provoked a stand-off known as the Munich Crisis -- and pushed the world to the brink of war.

Radio Bulletin (archival audio):... Adolf Hitler has moved up his deadline. Hitler has demanded 11,000 square miles of Czechoslovakian territory...

Susan Douglas, Historian: People were getting up in the morning listening to Hitler, you now, foaming at the mouth and they would be doing simultaneous translations of what Hitler was saying.

Radio translation of Hitler speech (archival audio): But it is a question from which I will not yield...

Susan Douglas, Historian: News bulletins began to get more frequent, Americans by September of 1938 were absolutely used to news bulletin interruptions, and it actually made radio really compelling.

Radio Bulletin (archival audio): Czechoslovakia will not yield even though Hitler's armies should come crashing across the border before Wednesday night...

T.J. Jackson Lears, Historian: We are Americans, and we want to believe that we’re going to be exempt from all of these tragic conflicts that are enveloping Europe. But we also sense the likelihood that we’ll be swept up in them, too.

Radio Bulletin (archival audio):... populaces are being given gas masks...

T.J. Jackson Lears, Historian: So, this is a period of not only great fear and anxiety but foreboding, foreboding about the future and what the future will bring.

Radio Bulletin (archival audio): Europe's most anxious days since the World War...

Narrator: It had been barely a month since the Munich Crisis -- a month of uneasy and profoundly uncertain peace. And now, from some obscure hamlet in New Jersey, came this:

Frank Readick (Carl Phillips, The War of the Worlds, archival audio): We are bringing you an eyewitness account of what's happening on the Wilmuth farm, Grovers Mill, New Jersey. Ladies and gentlemen, this is the most terrifying thing I have ever witnessed! Something wriggling out of the shadow like a gray snake. Now it's another one, and another. They look like tentacles to me.

Esther L. Hoadley, Chicago, Illinois (actor): And before I knew it, strange creatures were wafting out of the “thing,” and they were spraying crowd with light rays and the people were emitting -- no, bellowing agonizing noises, and Phil was screaming into the mike...

Frank Readick (Carl Phillips, The War of the Worlds, archival audio): A humped shape is rising out of the pit. I can make out a small beam of light against a mirror. Wait a minute, something's happening... There's a jet of flame springing from that mirror, and it leaps right at the advancing men... Good Lord, they're turning into flame! Now the whole field's caught on fire -- the woods, the barns, the -- the gas tanks of the automobiles. It's spreading everywhere. It's coming this way now, about 20 yards to my right --

Peter Bogdanovich, Film Director: The mic went dead. Silence. Orson was standing in the middle of the broadcasting studio and he just went like that -- hold it -- and he held the pause for the longest time. Just, like that.

Narrator: It was an inspired moment for Orson Welles, the 23-year-old director of Mercury Theater on the Air. Standing at the podium in Studio 1, on the 20th floor of the Columbia Broadcasting Service in New York City, with 10 actors and a 27-piece orchestra eagerly awaiting their next cue, Welles opted for deafening silence.

Peter Bogdanovich, Film Director: Orson was probably the greatest director of radio and the most innovative. I mean he broke all the rules that didn’t even exist.

Narrator: In theatrical circles, Welles was already widely considered a major talent. As an actor, he'd racked up an impressive roster of radio roles -- appearing, often anonymously, in as many as 25 different programs a week. Listeners who recognized his voice likely knew him as The Shadow, the enigmatic crime-fighter who was said to possess the power to cloud men's minds.

But it was as a stage director that he'd made his big splash, mounting a string of stunning successes for the New Deal Federal Theater Project. Welles' version of Macbeth -- set in Haiti with an all-black cast, and performed on a stage in Harlem -- had earned him a reputation as both prodigy and provocateur -- or as TIME magazine put it, "the brightest moon over Broadway."

Now, with his producing partner John Houseman, Welles had brought his unique sensibilities to the Mercury Theater on the Air -- a CBS-sponsored hour featuring radio adaptations of popular literary works.

Dracula Intro (archival audio): The Columbia Network is proud to give Orson Welles the opportunity to bring to the air those same qualities of vitality and imagination that have made him the most talked of theatrical director in America today.

Paul Heyer, Media Historian: The idea for The War of the Worlds actually came from Welles himself, who thought this would make a very interesting radio drama. His co-producer John Houseman did not think so but Orson told Houseman, “This is one of my favorite stories. I’m a great admirer of H.G. Wells.” Houseman kind of rolled his eyes a bit and suspected Welles had never read the story but just thought, “Well, it’s an idea and let’s see if it flies.

Narrator: In his novel, published in 1898, British writer H. G. Wells had woven a terrifying tale of destruction, in which Martian invaders wrecked havoc upon the English countryside. For the Mercury adaptation, Orson Welles had directed his writer, Howard Koch, to shift the setting to the United States.

Paul Heyer. Media Historian: Koch thought this was a job that was impossible. He didn’t welcome it. He wanted to do something else, but, again, Welles was insistent.

Narrator: On Monday -- seven days before the broadcast was slated to air -- a panicked Koch stopped at a gas station while driving along the Hudson River, bought a map of New Jersey, and later -- with his eyes closed -- picked out a spot for the Martian landing.

Paul Heyer. Media Historian: Grovers Mill, New Jersey -- that’s where the Martians were gonna land. And, today Grovers Mill is probably one of the most famous places in America for a historical event that never really happened.

Narrator: Over the next several days, with constant badgering from Houseman, Koch hammered out the draft script and on Thursday, a full company rehearsal was recorded to wax disc for Welles.

The disk was hand delivered to him at the St. Regis Hotel -- since, as usual, his frantic schedule prevented him from paying attention to the week's broadcast until the proverbial 11th hour. It was one or two o'clock in the morning on Friday, fewer than 72 hours before they went live on the air, when Welles finally heard the show -- and declared it abysmally dull.

Chris Welles Feder, Daughter of Orson Welles: So at the original meeting for The War of the Worlds everyone's opinion was, "Oh this is going to be so boring, it's so old fashioned, nobody is going to-- what can we juice it up, make it more exciting?"

Narrator: Earlier that evening, Welles had happened to catch a CBS broadcast of a play by Archibald MacLeish, entitled "Air Raid." The story was fiction -- but the form mimicked the style of a breaking-news flash.

Radio (archival audio): We've got them now. We see them. They're out of the dazzle. They're flying ... fighting formation in column. Squadron following squadron. Ten-- 15 squadrons. Bombing models mostly...

Susan Douglas, Historian: They’re slaving over this The War of the Worlds script and they’re trying to figure out how to bring it to life and then they come up with the idea of using news bulletins. Why not? It’s one month after the Munich Crisis.

Paul Heyer, Media Historian: These news bulletins were common fodder on the radio and Welles picked up on that. People are on pins and needles -- as we are today every time we say, “We interrupt this program to bring you a special news bulletin.” People worried that this could be serious.

Chris Welles Feder. Daughter of Orson Welles: I mean the concern that this was going to be some boring, old fashioned, dusty museum piece, they certainly went to the other extreme, didn’t they?

Narrator: On Friday, after hours of frantic re-writing, the script was delivered to the CBS legal department for review. Fearing liability for defamation, network attorneys flatly prohibited the use of real names for individuals and organizations, and requested no fewer than 28 changes.

Finally, Sunday came. At the afternoon dress rehearsal, Welles focused on ramping up the program's realism -- tinkering with the dialogue, pacing, and music cues. Meanwhile, actor Frank Readick -- slated to play the part of the on-the-spot reporter Carl Phillips -- went down to the CBS record library and, for inspiration, listened to the eyewitness account of the Hindenberg accident again and again.

Herbert Morrison, reporter (archival audio): It's burst into flames! Get this Scotty, get this Scotty! It's fall, it's crashing! It's crashing terrible. Oh my, get out of the way, please, it's burning and bursting into flames and it's falling on the mooring mast...

Frank Readick, Carl Phillips, The War of the Worlds (archival audio): Good Lord, they're turning into flame! (scream) Now the whole field's caught on fire… the woods, the barns, the the gas tanks of the automobiles… it's spreading everywhere! It's coming this way now, about 20 yards to my right -- (silence).

Announcer 2, The War of the Worlds (archival audio): Ladies and gentlemen, due to circumstances beyond our control, we are unable to continue the broadcast from Grovers Mill.

Interviewer (re-creation):Can you tell me the most frightening moment for you?

Mrs. Bertha Boughton, East Hampton, Long Island (actor): The awful silence of the broadcaster. I presumed he had fallen with the dead because he stayed to witness the awful sight until the last moment, at his own risk, to do his duty and be of service to the world.

Seymour Charles Hayden, Sunland, California (actor): Well, the organ music had just started when it was cut off and this voice was saying, “The cylinder lies in a deep crater. No signs of life evident. Blackened corpses are strewn about." Well, my lower jaw's down on my chest and I'm baring my ears out to assure I'm hearing alright.

Announcer 2, The War of the Worlds (archival audio): Ladies and gentleman, I have a grave announcement to make. Incredible as it may seem, both the observations of science and the evidence of our eyes lead to the inescapable assumption that those strange beings who landed in the Jersey farmlands tonight are the vanguard of an invading army from the planet Mars.

Paul Heyer, Media Historian: When it actually emerged during the broadcast that this was a Martian invasion, some people found that completely implausible and decided this was a radio drama. Other people thought, “Well, maybe, maybe there is intelligent life on Mars and this is them coming to eat us, literally.”

Gerta S. Brown, East Greenland, New York (actor): My neighbor came to the door excitedly. “Come quickly,” she said, “there's something on the radio I want you to hear."

“What is it about?” I asked. I was starting to get curious. “Mars men” came her reply. That was her reply. "Mars men," she said. I was still skeptical, but not for long. Hasn't science proved that there is life on Mars, through their observations?

Eric Rabkin, Writer: In 1938, the vast majority of people didn't live with light pollution. They could walk out of their house at night and they could look up in the sky. And for those of us who have looked up in the sky, Mars has always been unique because its color is there. It really is a different color than every other light that we see in the sky.

Narrator: Visible as an eerie red glow, Mars had inspired perplexed fascination for centuries.

Robert Crossley, Writer: Mars is just far enough away from the Earth that we can see it pretty well. You were able to see enough to get a sense that maybe this was an Earth-like planet, but you couldn't see quite enough to be sure what was there. So there was an intriguing sense of mystery about the planet.

Narrator: In the early 1900s, the speculation had turned frenzied -- sparked by astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli's observation of faint geometric lines crisscrossing the planet's surface. Schiaparelli called them canali, Italian for "channels" -- which was mistranslated as "canals."

Robert Crossley, Writer: Once canali got translated into English as canals, it brought along all the baggage that we associate with canals and particularly in the 19th century which was a canal building century. It's a word that inherently suggests engineering. If there are canals, there must be canal builders.

Narrator: Even as most scientists dismissed it, the idea of an industrious Martian race captured imaginations around the world, fueling wild theories and filtering into fiction, popular song and film.

Flash Gordon (archival audio): It's no use Flash. You mean we are going to crash on Mars? Look Doc, we are heading straight into the beam.

Narrator: As recently as 1924, the U.S. Army Signal Corps had asked radio stations across the country to shut down so that its engineers might listen without interference for signals from the Red Planet. And just three days before The War of the Worlds broadcast, the Christian Science Monitor had run a statement by a prominent Scandinavian astronomer, confirming the existence of "living things on Mars."

Eric Rabkin, Writer: Mars kept popping up, again and again. So, by the time Martians are reported to come down outside of New York City in 1938, it's not as if Mars isn't something that people could imagine.

Announcer 2, The War of the Worlds (archival audio): We take you now to field headquarters of the state militia near Grovers Mill, New Jersey. This is Captain Lansing of the Signal Corps attached to the state militia now engaged in military operations in the vicinity of Grovers Mill. Cylindrical object lies in a pit directly below our position, surrounded on all sides by eight battalions of infantry... Looks almost like a real war.

Narrator: By a quarter past eight eastern time, telephones were ringing madly all across the country, as concerned Americans tried to determine the whereabouts of relatives, warn friends and acquaintances, and, most of all, corroborate what they were hearing.

Man on the phone (archival): City Desk. A what?? Wait a minute.

Narrator: For the next several hours, newspapers, radio stations and police precincts from coast to coast would be swamped with calls.

Man on the phone (archival): Well I can't help that ma'am, we just don't know anything about it. Did I say something about a quiet Sunday evening?

Second man (archival): What's going on anyway?

Narrator: Soon, strange bulletins began coming in over the press service wires.In Bergenfield, New Jersey, not far from Grovers Mill, some 20 families turned up at a police station, with all of their household possessions piled into their cars. In Indianapolis, a woman rushed the pulpit in a Methodist church, shouting that the end of the world had come. And in Washington state, a spectacularly ill-timed power failure plunged the small town of Concrete into darkness -- and sent terrified residents fleeing into the mountains.

Announcer, The War of the Worlds (archival audio): The battle which took place tonight at Grover Mills has ended in one of the most startling defeats ever suffered by any army in modern times; 7,000 men armed with rifles and machine guns pitted against a single fighting machine of the invaders from Mars. One hundred and twenty know survivors…

Seymour Charles Hayden, Sunland, California (actor): Well, my wife she came in, my wife, just wringing her hands and wailing away, her eyeballs about to pop out onto her lap going, “What is it? What is it? What can it be? Is it the Germans?” Well, she hadn’t heard that word ‘Martians’, but I had.

Announcer, The War of the Worlds (archival audio):...a brief statement informing us that the charred body of Carl Phillips has been identified in a Trenton hospital.

David Roepik, Journalist: We think that we’re really smart, but if there’s a cue out there that could possibly be dangerous, we’re going to react to it protectively, instinctively -- fear first, and reason and fact second. And a stressed people back in those days by the Depression and talk of war and so forth is already pre-wired to be more sensitive to danger signals. Those drums are already beating.

Announcer 2, The War of the Worlds (archival audio): The rest strewn over the battle area from Grovers Mill to Plainsboro, crushed and trampled to death under the metal feet of the monster, or burned to cinders by its heat ray. Their apparent objective is to crush resistance, paralyze communication, and disorganize human society.

Sylvia Holmes, Newark, NJ (actor): We all felt it was the end of the world. It was a wonder my heart didn't fail me, because I'm nervous anyway. So I just ran out the house. I guess I didn't know what I was doing. I kept saying over and over again to everybody I met: "Don't you know? New Jersey is destroyed by the Germans -- it's on the radio."

David Roepik, Journalist: Alien, army, invader, in the late ‘30s, was quickly translatable from Martian to German because we default to what we already know. We’ve developed these mental shortcuts. We search our mental files of what we already know to see what it represents.

Newsreel (archival): ...Hitler liked to start invasions on the weekends. It was a way he said of catching other nations napping...

David Ropeik, Journalist: And those clues, they used all this language in the first few minutes of the broadcast. We’re very powerfully controlled by these things. They’re mostly subconscious. They’re mostly not a matter of free will.

Announcer 2, The War of the Worlds (archival audio): The monster is now in control of the middle section of New Jersey and has effectively cut the state through its center. Communication lines are down from Pennsylvania to the Atlantic Ocean. Railroad tracks are torn and service from New York to Philadelphia is discontinued.

Sylvia Holmes, Newark, NJ (actor): When I got home, I woke my nephew up. I looked in the icebox and saw some chicken left from Sunday dinner. I said to my nephew, "We may as well eat this chicken -- we won't be here in the morning."

Announcer, The War of the Worlds (archival audio): Highways to the North South and West are clogged with frantic human traffic.

Narrator: The clock in Studio One now read half past eight. Over the previous 12 minutes, Welles and his company had killed Carl Phillips, slaughtered the militia in New Jersey, and unleashed a full-scale Martian invasion of the United States.

Paul Heyer, Media Historian: One of the unbelievable things about the first part of the broadcast is how quickly everything happened. We know today that would never happen that quickly, the army ready in 15 minutes and so on but Welles set people up for this by the pacing. And people suspended their, their disbelief. The Svengali effect Welles had of hypnotizing millions of people over the airwaves made things appear as if they were taking place in real time.

Narrator: With the crisis at its peak, Kenneth Delmar stepped up close to the mic, and, as Welles had directed, delivered his best impersonation of Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Secretary, The War of the Worlds (archival audio) : Citizens of the nation: I shall not try to conceal the gravity of the situation that confronts the country, nor the concern of your government in protecting the lives and property of its people.

Paul Heyer, Media Historian: People knew that voice. And even though this voice was announced as the Secretary of the Interior people said, “We heard the President. We heard the President.” It was a case of, in their moment of anxiety, the non-verbal overwhelming the verbal.

Narrator: Mid-way through Delmar's speech, a telephone rang in the control room. The CBS supervisor in charge of the broadcast took the call and hurried out of the studio. When he returned a few moments later, as John Houseman recalled, he was "pale as death." Network executives had ordered the broadcast be interrupted with an identifying station break at once. The CBS switchboards were overwhelmed; listeners had to be told it was only a play.

Welles was then at the mic, the room was his -- and at that point in the show, there was no stopping him.

Operator Three, The War of the Worlds (archival audio): Newark, New Jersey, Newark, New Jersey... Warning! Poisonous black smoke pouring in from Jersey marshes.

Gerta Brown, East Greenland, New York (actor): My mouth, my mouth dropped open as I listened to the incoming announcements. The familiar names of cities: Bayonne...

Operator, The War of the Worlds (archival audio): Bayonne New Jersey calling Langham Field

Gerta Brown, East Greenland, New York (actor): ...and then New York and New Jersey cut off. Gas masks are useless. Men are dropping like flies.

Announcer, The War of the Worlds (archival audio): New York City, the bells you hear are ringing to warn people to evacuate the city as Martians approach. Estimated in last two hours three million people have moved out along the roads.

Josephine O'Cone, Summit, New Jersey (actor): I had become so frightened that I began to cry. I immediately ran downstairs, and grabbed my mother, my coat and key. I kept coughing and crying, “Mother, we are all going to die tonight. Mother, the black smoke is getting the best of me, can’t you smell it too?" And over and over in my mind these facts kept racing: take highways to open spaces, keep cool and calm, and beware of gas.

Announcer, The War of the Worlds (archival audio): Black smoke now spreading over Raymond Boulevard, gas masks useless, Earth's population...

Woman in car (archival): Bob, turn around, go back. Go back, Bob I want to go home...

David Ropeik, Journalist: They could smell smoke. They could hear things. They could see things. This sounds so irrational, wacky, dumb. It’s not. It is, if you think that the brain is this perfectly rational organ. That’s not how the brain works. It takes the facts, it runs them through feelings, and it comes up with judgments. And the feelings of fear have a very powerful, visceral, physical effect on people’s perceptions.

Announcer, The War of the Worlds (archival audio): Martian cylinders are falling all over the country. One outside of Buffalo, one in Chicago, St. Louis, seem to be timed and spaced...

Susan Douglas, Historian: There were listeners who looked out their windows and if they saw a lot of cars on the street, they were like, "Oh my God, everybody is getting out of here. We better get out of here too." There were people who looked out at the streets and the streets were empty and were like, "Oh my God, everybody has already left, we better get out of here."

Ingeborg Zimmer, Bloomfield, New Jersey (actor): I insisted to Mr. Zimmer that we drive anywheres – either into the phenomenons or away from them if that were possible. I grabbed my picture albums. I guess I figured I could show them to St. Peter, like "before and after" pictures, cause I figured when I saw him, I'd just be a charred piece.

E.M. Moody, Venice, California (actor):... We at this point had begun to measure our time on earth in a matter of a few hours, and then we changed to a Special Broadcast from a cathedral in New York City, describing five war machines that had lined up on the Hudson River and were preparing to destroy the city. The streets are jammed, the bridges crowded, people jumping into the river like rats...

Announcer, The War of the Worlds (archival audio): Times Square. People are trying to run away from it but it's no use...they are falling like flies...

Narrator: At 42 minutes past the hour, Welles finally delivered the station break -- a good ten minutes after CBS had demanded it.

Announcer, The War of the Worlds (archival audio): You are listening to a CBS presentation of Orson Welles and the Mercury Theater on Air in an original dramatization of The War of the Worlds by H.G. Wells.

Narrator: Of course, many who had been listening were at that point otherwise occupied.

Chris Welles Feder, Daughter of Orson Welles: By the time the second half of the show rolled on the air, people were packing their bags, jumping into their cars, heading for the hills, so I don't know how many people actually heard the second half. I would think not many.

Anna Farrell, New York, New York (actor): My sister and I started out for Long Island. And we hailed a cab and then we went in to a Cafe near 52nd on 8th Avenue. I told the Bartender about the end of the world. He tried to calm the pair of us down by saying, "Well, if the end of the world is here, why not take it with a smile?" And we did! We had a Scotch Highball a piece. We felt good that we were gonna die around a few men. Then we had the second one. Then at that time, we knew the Lord had sent us to the right place.

Interviewer (re-creation):Indeed!

Professor Pierson, The War of the Worlds (archival audio): I thought that I might be the last living man on Earth.

Narrator: As Welles ran out the broadcast, the deluge of calls continued to light up switchboards across the country. In some quarters, there were even vague reports of suicides and panic-related deaths.

Orson Welles, The War of the Worlds (archival audio): This is Orson Welles, ladies and gentlemen, out of character to assure you that The War of The Worlds has no further significance than as the holiday offering it was intended to be: the Mercury Theatre's own radio version of dressing up in a sheet and jumping out of a bush and saying "Boo!

William Guthrie, Los Angeles, CA (actor): My wife and I were driving through the redwood forest in northern California when the broadcast came over our car radio. I forgot we were low on gas. In the middle of the forest, our gas ran out. There was nothing to do. We just sat there holding hands expecting any minute to see those Martian monsters appear over the tops of the trees. All we could think of was to try and get back to Los Angeles to see our children once more. When Orson said it was a Hallowe'en prank, it was like being reprieved on the way to the gas chamber.

Sylvia Holmes, Newark, NJ (actor): It was eleven o'clock and we heard it announced that it was only a play. It sure felt good - just like a burden had been lifted off.

Narrator: At CBS, meanwhile, the ordeal was only just beginning.

Paul Heyer, Media Historian: Immediately after the broadcast the studio was inundated with police, and news reporters, and they cornered Welles and his co-producer, John Houseman and made it seem like the events were more serious: “Do you know about all those deaths on the highway as people were leaving New Jersey?” And they thought they were gonna be put into prison.

Narrator: "The following hours were a nightmare," Houseman would later say."...We were hurried out of the studio, downstairs, into a back office. There we sat incommunicado while network employees were busily collecting, destroying, or locking up all scripts and records of the broadcast."

By the next morning, October 31st, the Panic Broadcast was front-page news from coast to coast, with reports of traffic accidents, near-riots, hordes of panicked people in the streets -- all because of a radio play.

Florence Rohm, Bridgeville, PA (actor): It was like in a packed theatre and an announcement was made that the theatre was afire. Something like that would lead to the arrest and imprisonment of somebody. I don't know if that program violated any set laws, but it certainly was an example of “Wolf! Wolf!”

Narrator: On Capital Hill, Iowa Senator Clyde Herring called for legislation to create a national board of radio censors. The chief of the Federal Communications Commission ordered an investigation of CBS's conduct. Worse still, though it had been mere hours since the broadcast, the network had received scores of outraged complaints -- and some were forecasting a flood of lawsuits soon to follow.

Orson Welles (archival): I've had almost no sleep and I know less about this than you do. I haven't read the papers.

Narrator: With contrition the only sensible card to play, CBS executives hastily convened a press conference.

Orson Welles (archival): Of course we are deeply shocked and deeply regretful of the results of last night's broadcast...

Paul Heyer, Media Historian: The press conference was one of Welles great performances as an actor. And he knew that his whole career was on the line here. So he knew that he had to do something and show that he was sincere, which, according to Houseman, he wasn’t that sincere. He was pretty pleased with what he had unleashed with the broadcast.

Reporter (archival): Do you think there ought to be a law against such enactments as we had last night, as a result of that?

Orson Welles (archival): I don’t know what the legislation would be. I know that almost everybody in radio would do almost anything to avert the kind of thing that has happened, myself included.

Narrator: Pale and unshaven -- "looking," as he later put it, "like an early Christian saint" -- Welles was masterful in his astonishment.

Chris Welles Feder, Daughter of Orson Welles: You know, when somebody is as smart as my father was, it was very difficult for him to understand how anyone could fall for this. How could they?

Reporter (archival): Do you think you might have taken advantage of the public?.

Orson Welles (archival): I simply don't know. I can't imagine an invasion from mars would find ready acceptance. I was uh...

Chris Welles Feder, Daughter of Orson Welles: At the moment that he was shocked and dismayed he was also aware that suddenly his name was on the front page of every newspaper all over the world, that overnight he had become internationally famous as a result of this broadcast. I don't think he was sorry about that.

Narrator: For Welles, the only tangible consequence of the entire episode would come in the form of a reward.

Peter Bogdanovich, Film Director: Orson always said, “We always thought it was one of our lesser shows.” Of course it scared half the country, but what happened as far as the show was concerned, the Mercury Theatre on the Air finally got a sponsor.

Paul Heyer, Media Historian: Eventually Campbell Soup came in and it became the Campbell Playhouse. If Orson Welles could sell millions of people on the idea of a Martian invasion, imagine what he could do for Campbell Soup.

Chris Welles Feder, Daughter of Orson Welles: The War Of The World broadcast was really the turning point in my father’s career because before the broadcast he had been known in New York as a theater director. He had been known as a radio personality, but he was not an international star. And suddenly Hollywood was after him in a big way.

Narrator: Welles deftly parlayed his notoriety into an unprecedented Hollywood deal, signing a contract with RKO studios to write, produce, direct and star in one film a year. The groundbreaking Citizen Kane would soon follow.

Chris Welles Feder, Daughter of Orson Welles: When the Hollywood studios originally approached my father they wanted him to replicate in a movie The War of the Worlds radio broadcast. But of course once my father got to Hollywood the last thing he wanted to do was to make a movie based on The War of the Worlds. He wanted to do something new and fresh. He was, he was very excited about this new medium.

Narrator: The War of the Worlds would remain a defining moment for Orson Welles -- and for the nation he'd scared out of its wits.

Gerta Brown, East Greenland, New York (actor): Sincerely, when I hear a News Bulletin coming over the radio, in the future I shall say, “Gerta, this is just another one of that Orrie Welles’ hallucination, you know, think nothing of it,” whereupon I shall definitely be soothed.

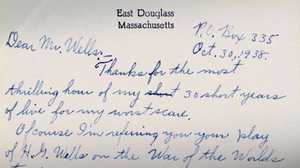

Narrator: In the wake of the Panic Broadcast, thousands of ordinary Americans wrote letters -- to the FCC, to CBS, and to Welles himself -- offering praise for the program...

Actress 1 (audio): Gentlemen, An orchit to you, and to all the cast of War of the Worlds! Alos, shame on you for giving me the scare of my life!

Actress 2 (audio): Let me congratulate you on your broadcast...

Actor 1 (audio): Thanks again for a wow of a thrill

Actor 2 (audio): More power to you...

Actress 3 (audio): ... the Martians visitation upon this earth was a masterpiece of realism.

Narrator: ...as well as bitter condemnation.

Actress 4 (audio): ...a horrible prank to play on innocent, unsuspecting people.

Actor 4 (audio): ...a very grave mistake...

Actress 5 (audio): ...Having spent the most horrifying night...

Actor 5 (audio): It think the safest place for you is Mars, take a rocket and get going.

Louis F. Heidenrich, Burns, Oregon (actor): For those of us that love our country, we don’t want that kind of hoax put over the air. We want government regulated radio. We are opposed to every little city in this country getting a radio station and putting whatever they want over the air. We need a radio dictator.

Narrator: But what rankled many was not the broadcast itself, but what the reaction revealed about the American people.

Interviewer (re-creation): So you yourself did not believe the hoax?

Daniel O'Grady, Department of Philosophy, University of Notre Dame, Indiana (actor): No, those who were deceived by dramatic reenactment would, in an ideal society, be sterilized and disenfranchised. Such damn fools. It shakes one’s faith in democracy to think that such hysteria and panic can affect those who are supposed to vote intelligently next week.

Narrator: It was a complaint echoed in the newspaper coverage of the broadcast, which continued unabated for two full weeks and amounted to some 12,500 articles in total. Over and over again, editorial pages blamed the listener.

To journalist Dorothy Thompson, who applauded Welles in her widely-read column, the episode had cleverly proved the power of propaganda. As she put it, "Hitler managed to scare all Europe to its knees a month ago, but at least he had an army and an air force to back up his shrieking words... Mr. Welles scared thousands into demoralization with nothing at all..."

T.J. Jackson Lears, Historian: Radio is able to convey a single voice to an enormous mass audience where unprecedented numbers of people can be addressed at the same time, for the same purpose, to the same end, by the same spellbinding orator. And it remains to be seen what the consequences of that may be. They may be as benign as a Fireside Chat, which whips up support for Social Security, or they may be the Nuremberg Rallies, or they may simply be the fearful family huddled together around the radio listening to reports of the Munich Crisis or the men from Mars landing in New Jersey.

Announcer, The War of the Worlds (archival audio): Scouting planes report enemy machines increasing speed northward, kicking over houses and trees in their evident haste...

T.J. Jackson Lears, Historian: People who are concerned about democracy and about vigorous public debate begin to think, “This is scary, you know, that propaganda can work so effectively, and we Americans have gotta figure out ways to resist it, to create institutions that will resist it.”

Narrator: In the end, all the national hand-wringing would come to nothing. On December 5th, five weeks after the broadcast, the FCC concluded its investigation -- announcing, to CBS's great relief, that it would take no punitive action against the network. CBS, in fact, had voluntarily promised restraint already, making what amounted to a gentleman's agreement with the FCC to avoid the use of dramatized, simulated newscasts in the future.

Of the many suits brought against Welles and CBS, meanwhile, none resulted in the payment of damages. Ultimately, the very extent of the panic would come to be seen as having been exaggerated by the press. But there was no disputing that something had happened that night in 1938 -- and it would haunt the nation for decades to come.

T.J. Jackson Lears, Historian: It’s such a key moment in the history of American emotional life in the 1930s. The atmosphere of fear and anxiety, the longing for reassurance, but the sense that at any moment destruction might come from the sky, come from abroad, or come from within this country, I think The War of the Worlds spoke directly to those fears and anxieties.

David Ropeik, Journalist: The reaction wasn’t just entertainingly irrational - I think it’s hard to fault the people who overreacted to the program. The systems for survival easily readily, emotionally, powerfully, overwhelm the rational. That’s a really powerful physical reality that came from something that’s intrinsic in the human animal. It’s a truth about us all.

Josephine O'Cone, Summit, New Jersey (actor): I know I will remember the night of Sunday, October 30th, 1938 for as long as I live. And no one can share my feelings because I cannot explain them. But I hope that no one, not even the worst of people, ever feels the way I did last night. And I hope and pray I never hear anything like it again because it was the most awful thing I ever heard.

Orson Welles, The War of the Worlds (archival audio): So goodbye everybody, and remember, please, for the next day or so the terrible lesson you learned tonight: that grinning, glowing, globular invader of your living room is an inhabitant of the pumpkin patch, and if your doorbell rings and nobody's there, that was no Martian -- It's Halloween.

Slate: The first person reports dramatized by actors in this program were taken from the accounts of actual listeners.

Anna Farrell, New York, New York (actor): Dear Mr. Orson Welles, Enclosed please find bill for the amount of $2.10 which is for six highballs. Now don't get angry, I think some one must give you a laugh. I will settle for a pair of tickets to your theatre or the Kate Smith hour. Isn't that fair enough? Respectfully, Mrs. Anna Farrell. P.S Have since given a laugh to hundreds who did not hear the broadcast and many who still think we are nuts!