Papyrus

PBS air date: November 21, 2006

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: When I was a kid, I used to play this

game, Password(TM). And the secret password is always

invisible, hidden until you slid the paper into this sleeve, and then the

secret word is revealed.

Well, what if the secret words aren't part of a kids' board game, but

instead are on a crumbling, ancient manuscript?

Correspondent Beth Nissen caught up with investigators who are uncovering

secret messages that have stayed hidden for 2,000 years.

BETH NISSEN (Correspondent): In these vaults, on these

shelves, in these boxes at Oxford University, ancient clues—2,000 years

old—to a glorious human past; wrapped in printed paper, fragments of

ancient paper, pieces of the D.N.A. of Western Civilization.

ROGER T. MACFARLANE (Brigham Young University): Here's one that

contains a large page of Homer's Odyssey, still with quite a bit of mud

and sand clinging to it.

BETH NISSEN: These are only a few of the faded fragments found

buried near the outskirts of what was, at around the turn from B.C. into A.D.,

a mid-sized capital city in Greek-ruled Egypt, the city of

Oxyrhynchus—actually, found buried in the Oxyrhynchus city dump, in

rubbish mounds.

ROGER MACFARLANE: There can be more Homer, new pieces of Sophocles,

Euripides, other authors who were being read in antiquity. You never really

know what's going to come out of the box.

BETH NISSEN: Or whether what comes out of the box can be read.

JOSHUA D. SOSIN (Duke University): Abrasion, dirt, clay, silt: an

awful lot can go wrong, when something is buried underground for 2,000

years.

BETH NISSEN: Yet somehow, buried above the water tables and

beneath the dry sands of Egypt, for all those centuries, almost half a million

of these papyri fragments survived, these pieces of ancient paper made from

papyrus.

JOSHUA SOSIN: Papyrus is a plant. It is a reed that grows almost

exclusively along the banks of the Nile. You shave the stalk into thin

strips, lay them parallel to each other, lay strips running perpendicular to

them; you pound it or press it, such that the cell walls break down. Cellulose

seeps out, creating a kind of gooey natural glue that binds the strips

together, which can then be pressed, polished and written on. The stuff is

really quite durable, in a way, more durable than the paper you're used to

taking notes on today.

BETH NISSEN: The tons of this reedy paper found at Oxyrhynchus

documented the daily life of an ancient city's markets and businesses and

courts.

JOSHUA SOSIN: We have marriage contracts, divorce contracts, tax

declarations, census registers, hate mail, dinner invitations. We have

letters-home-to-Mom. You name it, we have it on papyrus.

BETH NISSEN: Thousands more of the Oxyrhynchus fragments were

unreadable, soiled, grimy.

BENJAMIN HENRY (The University of Texas at Austin): Because this

was a rubbish dump, things get charred—if burning waste was put on top of

them —or stained.

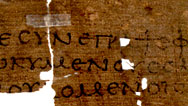

BETH NISSEN: Or, like this fragment, which looks, at first,

like the work of, say, Jackson Pollack of Crete. The only readable word of

Greek is just visible at the very bottom. You can read "Christos."

BENJAMIN HENRY: Yeah, there's "Christos," kind of a row sigma with a bar

above it. So that's the abbreviation for "Christos," you know it's a Christian

text. But much of it is totally illegible.

BETH NISSEN: And papyrologists assume there are letters there.

Papyrus was too expensive to throw away unused and often had writing on both

sides. But texts like this were a tantalizing, frustrating mystery.

BENJAMIN HENRY: Really, you're never going to be able to publish a text

like this. You can look at that under the microscope as much as you like, but

it's just a complete mess.

BETH NISSEN: What papyrologists really needed was

this—an equivalent to Superman's x-ray vision—a way to see through

whatever was on the surface of papyri—ancient food stains, burn marks,

mummy paint—see through to the writing underneath.

As the ancient Greek scientist Archimedes is said to have said from his

bath: Eureka!

It's called multispectral imaging, a technology developed by NASA to "see

through" clouds of gas in space.

ROGER MACFARLANE: It was a significant step forward, when a scholar at

NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory decided to apply the technology to texts.

BETH NISSEN: Ancient texts, written on papyri.

The project today: see if multispectral imaging can help scholars at the

University of California at Berkeley read part of an account of the Trojan War,

by the poet Dictys of Crete, a part obscured by a large reddish stain.

ROGER MACFARLANE: Some people think it's a spill, a chemical spill

perhaps, or a spot of wine that was dropped on it. Even the best papyrologists

who've worked on this are usually not able to pick out any more than a few

scattered letters in here, and even at that, they feel like they're

guessing.

BETH NISSEN: The fragile fragment is put on a moving imaging

bed under a scientific-grade digital camera, which captures high-definition

images of the fragment, through a succession of color filters, one filter at a

time, a dozen different filters in all.

ROGER MACFARLANE: Each individual filter allows only a certain portion

of the light spectrum through.

BETH NISSEN: The light in the range of the spectrum visible to

the naked eye, reflects off whatever is on the surface of most of the papyri

pieces, the stains, dirt, mummy paint, whatever. The camera can't see much more

through these filters than the eye can, which isn't much.

But results tend to be better, using the filters that let in the range of

the light spectrum the human eye cannot see.

ROGER MACFARLANE: I've seen the best results in the infrared at 950

nanometers.

BETH NISSEN: Light in the infrared part of the spectrum,

invisible to the naked eye but not the camera, is more likely to pass through

what's on the papyrus surface to the ink underneath. Surface stains and dirt

fade away. The inked letters appear; black magic.

BENJAMIN HENRY: Ink, which is pretty much pure carbon—it's made

out of soot mixed with glue—will absorb all of the infrared, and so it

will come out black.

BETH NISSEN: Every time they see this 21st century technology

work on first or second century fragments, papyrologists are thrilled, or as

thrilled as papyrologists get.

ROGER MACFARLANE: None of us is really inclined to give high-fives and

celebrate too much, but we were really pleased.

BETH NISSEN: They've been pleased with multispectral imaging

at Oxford, too— home of the world's largest collection of ancient papyri:

all those fragments excavated from the Oxyrhynchus city dump.

They have as many as 500,000 fragments, but only about one percent have

been read and published by the few scholars working on them. Uncounted

thousands are illegible, in shreds, soiled.

BENJAMIN HENRY: There are fragments there that we'd pretty much

completely given up all hope of ever being able to read.

BETH NISSEN: Like that Jackson Pollack-y fragment that had the

word "Christos" on it.

BENJAMIN HENRY: We put it under the multispectral imaging camera, and,

all of a sudden, the background completely drops out, and wherever there was

ink, you can read the ink as clear as the day it was written.

BETH NISSEN: And what was written? A passage from the New

Testament, St. Paul's "Epistle to the Romans," Chapter 14, Verses 7-9.

BENJAMIN HENRY: And then "Eis touto gar Christos apethanen," "for this

reason did Christ die." And it is now our earliest copy for these verses. We

did have another third century papyrus of the "Epistle to the Romans," but it

actually is very fragmentary. But now, we've got a complete text of these

verses in a late second and early third, perhaps, century copy.

JOSHUA SOSIN: I don't know how long we have, until the things sitting in

shoeboxes in this or that university turn to dust, but we've got to get

rolling. There are a great many, I mean, many thousands of papyri that are

sitting in boxes in dark hallways, waiting to be read.