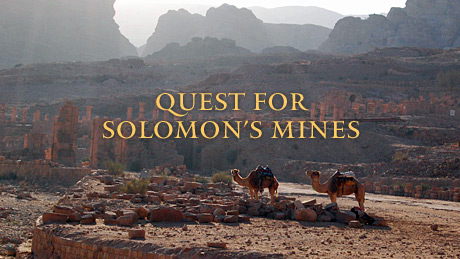

Quest for Solomon's Mines

Archeologists seek the truth about the Bible's most famous king and his legendary riches. Airing November 23, 2010 at 9 pm on PBS Aired November 23, 2010 on PBS

Program Description

Transcript

Quest for Solomon's Mines

PBS Airdate: November 23, 2010

NARRATOR: King Solomon: son of David, ruler of the first great Israelite kingdom, builder of the first temple in Jerusalem. The Bible tells us Solomon was not only the wisest, but the richest of all kings, but where did his wealth come from? Legends tell of fabulous mines of gold and copper, but where were they? Archaeologists have searched for evidence of Solomon and found nothing.

ERIC CLINE (The George Washington University): So far, there is absolutely no evidence for Solomon outside the Bible.

NARRATOR: Now, in the deserts of Jordan: mineshafts carved from bedrock a hundred feet deep, and the remains of ancient smelting.

THOMAS LEVY (University of California, San Diego): We have industrial-scale metal production, layer after layer.

NARRATOR: Are these King Solomon's mines? Are these the bones of his miners? At last, new finds from Solomon's era: ancient cities and the first evidence of early Hebrew writing, clues to the real world of the great biblical king.

The Quest for King Solomon's Mines, right now, on this NOVA/National Geographic Special.

Solomon: in the Bible, the wise ruler of a magnificent Israelite kingdom, a star on the stage of the ancient Near East.

BIBLE VOICEOVER (1 Kings 10:24): All the world came to pay homage to Solomon and to listen to the wisdom which God had put into his heart.

NARRATOR: The kingdom created by his father, the warrior-king David, under Solomon, reached new heights of power and prosperity.

BIBLE VO (2 Chronicles 9:22-24): King Solomon surpassed all the kings of the Earth in wealth and wisdom. They brought him tribute: silver and gold objects, robes, weapons and spices.

NARRATOR: In addition to his vast wealth, the Bible tells us Solomon was a great builder. In Jerusalem, he built the famous Temple of Solomon to house the Ark of the Covenant, spiritual focus of the newly unified Israelite kingdom.

Three thousand years later, he is still revered by all three of the Holy Land's great faiths: the Jewish people love Solomon because he built the first temple; to Christians, he is the wisest of Old Testament kings; Muslims, too, claim him as one of their own, the great prophet, Suleiman.

But no conclusive archaeological proof of Solomon or his great kingdom has ever been found, few traces of his palaces, temple or the sources of his vast wealth. His century, the 10th century B.C., remains a mystery.

ISRAEL FINKELSTEIN (Tel Aviv University): In the 10th century B.C., there are things which we know, but it's like a puzzle. Much of the puzzle is dark, and here and there you have lights in the puzzle.

NARRATOR: Many scholars have questioned whether Solomon was a great king at all.

THOMAS LEVY: Archaeologists and biblical scholars have been arguing about whether or not David and Solomon were magnificent kings or simple chiefs.

NARRATOR: If they were great kings, where did they get their wealth?

Now, for the first time a provocative find may help answer this question: ancient mines, their shafts disappearing deep beneath the sands of Jordan; and bodies. Were these the miners? And who was their master?

King Solomon's mines were never mentioned in the Bible, but over the centuries became the stuff of legend, popularized by a 19th century adventure story and no less than three Hollywood movies.

Are these the real King Solomon's mines? Were they the source of the wealth the Bible chronicles?

New finds are reshaping our image of the ancient world, giving credence to some of the Bible's historical accounts, but also casting an entirely new light on Solomon's era. Our quest for Solomon's world begins, not in Israel, but far to the east: Petra, an ancient trade center, built over 2,000 years ago, in the highlands of Jordan.

In the mountains around Petra, lie the ruins of an ancient kingdom called Edom. For over a decade, archaeologist Tom Levy has been researching the evolution of that Edomite kingdom.

According to Genesis, the Edomites, descendents of Jacob's brother Esau, created a kingdom even before ancient Israel. The remains of Edomite settlements cling to the mountaintops and plateaus high above Petra. Tom wants to know about the sources of wealth behind the Edomite kingdom.

His search has led him down from the highlands into the baking desert cauldron of the Dead Sea Rift Valley. It was here, in the no-man's land between ancient Israel and Edom, that he discovered the clues he was looking for. In an area called Wadi Feynan was an entire valley covered with a mysterious black rock. This was solidified slag, the waste product of metal smelting and on a massive scale.

Nearby, multiple shafts dug through rock and, far underground, tunnels, stretching deep inside the hills. And everywhere a striking blue-green rock: the unmistakable evidence of natural copper.

The slag, the mines, the copper, it all added up. This was an ancient copper mining and smelting complex, perhaps the source of wealth behind the Edomite kingdom.

THOMAS LEVY: Most scholars had assumed that it was traderoutes that stimulated the rise of the Edomite kingdom, but I thought that metal production and mining might be a key factor.

NARRATOR: The local people called it Khirbet en Nahas

THOMAS LEVY: Khirbet en Nahas, in Arabic, means "the ruins of copper." As you can see around us, the site is just covered with heaps of black industrial slag.

NARRATOR: Tom has been excavating this site for almost 10 years. He has shown how ancient smelters separated pure copper from the ore in which it's found, then spewed out slag, the molten waste product of the process.

The layers of slag reveal an astonishing record of hundreds of years of ancient copper production.

THOMAS LEVY: I'm really excited about this. Look, right before us we have industrial-scale metal production; layer after layer, almost like a book that, page by page, would reveal the history of metal production at this site.

NARRATOR: Tom believes that metal production played a key role in the evolution of not only Edom but of ancient Israel, too. For ritual and prestige, weapons and tools, metals helped turn simple agrarian societies into kingdoms.

Ancient peoples discovered that, from blue rocks like these, a mysterious new substance could be created. When heated, it was soft and malleable; when mixed with tin, cooled and polished, it had a magical luster. The Stone Age was over. The age of metals had begun.

Tom's student, Erez Ben-Yosef, has been trying to find out how those first copper-producing techniques evolved.

EREZ BEN-YOSEF (University of California, San Diego): It's really, as you see, a pit in the ground. We have the copper ore here. We need to crush it, and then we need to sort out the copper-rich fragments. You will see it's not easy.

NARRATOR: Ancient metalworkers needed a way to raise the temperature of their charcoal fires to over 1,200 degrees Celsius, the point at which copper separates from ore.

They did that with blow pipes.

EREZ BEN-YOSEF: We need three people constantly blowing.

NARRATOR: It takes Erez and his friends two hours of constant blowing before they see the first signs of smelting.

EREZ BEN-YOSEF: Can you see the blue flame? This is a good indicator that the smelting process is actually taking place.

NARRATOR: When they finally take the crucible out of the fire, they hope to find tiny droplets of copper in the bottom.

EREZ BEN-YOSEF: Alright, yes, that's how it looks like. It looks like that.

Very few...

RESEARCHER: There's another one here.

EREZ BEN-YOSEF: It's tiny, tiny, but it's metal!

RESEARCHER: It's a copper color.

NARRATOR: That's an awful lot of work for very little metal, but for thousands of years, this is how people smelted copper. The difficulty of producing it may have been why it was largely used for ritual objects and ornaments.

But that small-scale village production is not what Tom has discovered at Khirbet en Nahas. Over years of excavation, his team from the University of California at San Diego has revealed the remains of a massive operation, a copper producing factory.

The site is so large, they send up cameras attached to helium balloons to get a better sense of its scale. The aerial photos clearly reveal the structures of the ancient factory: a fortress and gate house, an administrative building, a tower, a temple.

The site was enormous. Its massive walls, buildings and slag heaps covered an area of 25 acres. Up to a thousand men worked here, day and night, feeding the furnaces where the copper was smelted.

Erez Ben-Yosef is excavating one of those smelters.

EREZ BEN-YOSEF: It's like a treasure for us to try and actually reconstruct the technology, step by step.

NARRATOR: At the moment, Erez is unearthing the business end of the smelter: the nozzles, called "tuyeres," where the air from the bellows blasted into the smelter.

EREZ BEN-YOSEF: It's the nozzle of a bellow pipe. And it's just one of the best preserved tuyere we have seen in this area.

NARRATOR: The nozzle of a bellow pipe may not sound like a great find, but to Erez, it's crucial evidence for the technological innovations that made large-scale smelting possible.

EREZ BEN-YOSEF: We will try to take it out. If we can take them from this side...try not to break them.

Alright, okay, that's a nice one. You can see the nozzle, but it's all covered with slag. And this was the hottest place in the furnace. You can see even some copper prills in the slag, some actual copper metal.

NARRATOR: Beneath the slag, the nozzle has been carefully made from layers of fired clay. This was necessary for it to withstand the 1,200-degree temperatures of the furnace.

This new shaft furnace was powered by foot bellows providing a steady stream of air into the smelter.

EREZ BEN-YOSEF: During the second millennium B.C.E., we have the introduction of this amazing shaft furnace that made this copper production process much more efficient.

NARRATOR: With men working day and night, copper could be produced on an industrial scale, and it was.

Environmental scientist, John Grattan, is discovering ancient pollution, a measure of just how intensive this copper production was.

JOHN GRATTAN (Aberystwyth University): I'm using this instrument, which measures metals in the environment, to see and map where the pollution actually is.

It says there is nearly 7,000 parts per million copper, just in the small sample I've taken. That's really nearly 7,000 times more than is safe to be in the soil. And, as if copper wasn't bad enough, looking down here, I can see extremely high levels, dangerously high levels of lead, zinc, arsenic. And this is just on this one tiny spot.

NARRATOR: Using a state-of-the-art X-ray fluorescence device, John Grattan has found powerful confirmation of the scale of ancient copper smelting at Khirbet en Nahas.

Copper was no longer an ornament, it was a commodity, vital for tools, weapons and buildings. Demand for the precious metal exploded, turning the Dead Sea Rift Valley into an industrial powerhouse.

JOHN GRATTAN: We've got here the evidence of the earliest industrial revolution and what I see as the birth of the modern world.

NARRATOR: But how did they get the tons of copper ore they needed to power this revolution?

Over 15 mines have been found, cut into the copper-rich hills surrounding Khirbet en Nahas. Project co-director, Jordanian archaeologist Mohammed Najjar, is exploring one of them.

MOHAMMAD NAJJAR (University of California, San Diego Levantine Archaeology Lab): During our work here, we find out that the shafts are from 3,000 years ago.

NARRATOR: Many of the mines were over a 100 feet deep, to reach the copper seams far below ground. Even with modern climbing gear, the descent is perilous.

MOHAMMAD NAJJAR: It's not easy to go down or up. We know that probably ancient miners were inside the galleries, inside the mines, for many months.

NARRATOR: Dr. Najjar and Tom both believe the miners were slaves.

THOMAS LEVY: This was not the kind of work that anyone would want to do, even for pay. In order to mine on this industrial scale, some sort of forced labor system must have been in existence.

NARRATOR: Imprisoned in claustrophobic tunnels far underground, the miners hacked out the copper-bearing rocks that fed the smelters of Khirbet al Nahas. Above ground, camel trains waited to transport the copper ore to the smelting site.

THOMAS LEVY: Okay, guys, we're going to take our ore.

NARRATOR: To understand the copper ore supply system, Tom Levy is recreating one of those camel trains.

THOMAS LEVY: We want to try an experiment, what it would be like to actually take ore that would have been mined in one of these mines. We've got one right behind me here. And by having these camels and our Bedouin friends helping us, we'll be able to reconstruct that process.

NARRATOR: They've discovered that a single camel can carry about 300 pounds of ore. But, usually, that ore is only 10 percent copper and 90 percent useless rock. So for every 30 of pounds of pure copper, they needed at least a camel-load of ore.

That means that 3,000 years ago, ancient camel supply trains like this probably made their way through these same desert wadis every day, all heading for the largest copper smelting site of the Dead Sea Rift Valley, Khirbet en Nahas.

The size of the slag heaps indicates that, over its lifetime, the site produced 5,000 tons of copper, enough to supply copper to the entire region.

Isotope analysis of copper objects from sites all over ancient Israel has proved that they came from the Wadi Feynan area.

AMIHAI MAZAR (Hebrew University of Jerusalem): Right in Israel, metallurgical studies of copper objects found in contexts of 11th century, late 12th and 11th century B.C., were proven to originate from Feynan.

NARRATOR: Perhaps this copper even reached Jerusalem, where Solomon built his temple.

THOMAS LEVY: The Bible tells us that the temple would require precious metals, including tons of copper. And the closest source of copper for Jerusalem—it's about a three-day ride from here—is this area of Feynan.

BIBLE VO (1 Kings 6:12-14): Then the word of the Lord came to Solomon, saying, "Concerning this house which you are building, if you keep all my commandments, I will dwell among the children of Israel and will not forsake my people." So Solomon built the temple.

NARRATOR: In the outer rooms, he placed elaborately carved figures and massive pillars, and, according to the Bible, all were cast in gleaming copper.

BIBLE VO (1 Kings 6:19-20): The inner sanctuary he prepared, setting there the Ark of the Covenant of the Lord. And he overlaid it with pure gold.

NARRATOR: If Solomon's temple and his palaces existed, they would have needed a lot of copper. So who controlled the burgeoning copper industry of the Dead Sea Valley? One thing is for sure, it had to be an advanced society.

MOHAMMAD NAJJAR: Copper production involves many different activities—mining, then smelting, distributing—you need management to do that. And that can be done only by a complex society.

THOMAS LEVY: It had to have been controlled by something as complex as an ancient kingdom. The question arises, what kingdom?

NARRATOR: Khirbet en Nahas was in the no-man's land between three ancient kingdoms. Any one of them could have had a hand in copper production.

To the west was ancient Israel; to the east, Edom; far to the southwest, the great power of the region, Egypt.

THOMAS LEVY: While I was sitting over there, my colleague, Dr. Najjar, was waving his arms furiously, said, "We just found something. It's an Egyptian scarab."

NARRATOR: The scarab suggests that at one time Egypt was an important player here.

Based on this and other evidence, like an Egyptian shrine at a nearby site, it's clear that in the centuries preceding Solomon, Egyptians controlled the copper industry of the Dead Sea Valley.

EREZ BEN-YOSEF: Undoubtedly, we had Egyptians here, running the mines. They had the control during the 13th century.

NARRATOR: But then, in the 12th century B.C., unexplained events shook the ancient Near East.All of its great civilizations fell.

AMIHAI MAZAR: Around 1200 B.C., the entire political structure of the Bronze Age collapsed. First, the Hittites in the north, the Mycenaeans on the west, and, finally, the Egyptian Empire collapsed and left a great void.

NARRATOR: In this political void, new powers emerged.

ISRAEL FINKELSTEIN: We basically have a vacuum. This collapse took down the big empires and opened the way for something new.

NARRATOR: In the area of Khirbet en Nahas, that something new was the rise of ancient Israel and Edom.

Tom believes these are the only two candidates for control of the copper mines. The more likely is nearby Edom. And now, a new find near the smelting complex may confirm that. It's an ancient cemetery.

THOMAS LEVY: These were circular graves with a cyst burial in the middle, which is like a stone-lined box, and capstones on top of it. We're hoping that by the end of the day, we'll be ready to lift those capstones.

So, the moment of truth has arrived. This is windblown sediment here. This tomb looks like it's going to be filled with sediment.

NARRATOR: It seems they are in for a disappointment. They are not the first to open this grave.

THOMAS LEVY: It looks like it's been disturbed in antiquity. We had hoped that we would pop these stones and find a beautiful pristine grave, but let's wait. Archaeology is about patience.

Okay, so this is five.

NARRATOR: But before long, good news. They catch their first glimpse of bone.

THOMAS LEVY: It looks like we've got a skull.

There's a lot of pieces missing. It's possible that we're going to have an articulated skeleton extending here, so that's exciting.

NARRATOR: Carefully, Tom's team starts the process of extracting the skeleton from the sand which has encased it for 3,000 years. Finally, the entire skeleton is revealed. This is a fully articulated skeleton in a crouched position, almost a fetal position.

So did this man have any connection with the mines?

If he did, his teeth and bones would contain copper and lead, the telltale traces of copper smelting.

Samples are crushed and dissolved, then analyzed in a mass spectrometer to reveal their chemical composition. The results are compared to skeletons from before the copper revolution.

MARC BEHEREC (Grad Student, UCSD): The remains from the cemetery have four times as much copper and lead content as the prehistoric remains.

THOMAS LEVY: That may mean that we've identified some individuals that were actually involved in the smelting activity.

NARRATOR: Even though this man was probably one of the copper workers, there was nothing in the grave to suggest his ethnicity. But artifacts from the cemetery and pottery found nearby provide the answer. The people buried here were from this region.

MOHAMMAD NAJJAR: We are talking about ceramics and different finds here. What we have here is Edomite.

NARRATOR: The discovery that the workers at Khirbet en Nahas were probably Edomite seems to confirm assumptions about the dating of the mining complex.

THOMAS LEVY: I assumed, like the scholarly consensus of the time, that it must date to around the seventh century B.C.E.

NARRATOR: That seventh century B.C.-dating was crucial to Tom's first understanding of what went on here.

He knew that Egypt had collapsed in the 12th century B.C., along with all the other great empires of the region. Based on the timeline of kings laid out in the Bible, Solomon's Israel flourished in the 10th century B.C.

The rise of the Edomite kingdom has traditionally been dated to the seventh century B.C. So with the evidence from Khirbet en Nahas pointing to Edom, it made sense the smelting complex would be from the seventh century, too.

To confirm that dating, Tom has brought radiocarbon specialist Tom Higham, from the University of Oxford to help him.

At the guardhouse and the slag heap, they look for samples of organic material that can be dated: twigs, pieces of charcoal, date seeds spat out by the miners.

THOMAS HIGHAM (University of Oxford): Well, in order to get really precise dates, we have to have a sequence of samples.

THOMAS LEVY: So you're saying we need samples from all these sedimentary layers?

NARRATOR: A sequence of samples allows them to create a chronology. All the dates need to be consistent or the whole sequence is called into question.

Tom Higham takes the samples back to the lab at Oxford. Radiocarbon dating combined with modern statistical analysis will allow him to calculate their age to an accuracy of plus-or-minus 30 years.

The result is really a surprise.

THOMAS HIGHAM: We've got the preliminary results here that you can see on the screen, and what is immediately apparent is that the samples are all fitting in the 10th and 11th century.

NARRATOR: This means the mines were operating, not in the seventh century B.C., but three to four centuries before that.

THOMAS HIGHAM: We're able to say with a great deal of confidence now that these sites were operating in the 10th and 11th centuries B.C. There is absolutely no question about it.

NARRATOR: The dating has thrown the team a curveball. According to the well-accepted archaeological chronology, there was no Edomite kingdom in the 11th or 10th century B.C. that could have controlled these mines.

Is this evidence of an earlier Edomite kingdom? If so, it might lend credence to the Bible's accounts of David's campaigns against the Edomites.

THOMAS LEVY: The Bible tells us that David conquered Edom and established strongholds over the area, like the fortress at Khirbet en Nahas.

BIBLE VO (2 Samuel 8:14): He stationed garrisons throughout Edom, and all the Edomites became vassals of David.

THOMAS LEVY: The fortress that we found at Khirbet en Nahas is similar to other fortresses found in ancient Israel.

NARRATOR: Could it be that David invaded Edom to get hold of its copper? If so, his son Solomon would have inherited these mines. But was the kingdom of David and Solomon advanced enough to control the copper industry of the Dead Sea Rift Valley?

The biblical account of Solomon's kingdom makes it sound so huge and powerful that controlling the Dead Sea Rift Valley would have been no problem.

BIBLE VO (1 Kings 4:21): And Solomon ruled over all the kingdoms from the Euphrates to the land of the Philistines and to the border of Egypt.

NARRATOR: But in the last 20 years, archaeologists have cast doubt on that story.

For decades, they have searched for evidence of the great 10th century B.C. kingdom of David and Solomon and found almost nothing.

There are a few clues. A carved inscription from the 9th century B.C. records the victory of an Aramean king over what it calls "the House of David," good evidence for David, but not necessarily for a great kingdom. Ruins in Jerusalem, claimed to be the City of David, have still not been conclusively dated. Some archaeologists believe they are from a later period.

The same uncertainties surround the kingdom of Solomon described in the Bible. Few doubt that David and Solomon existed. There is just no proof they were great kings capable of commanding a copper industry like Khirbet en Nahas. Some believe they were more like tribal chieftains.

If that is true, how did the Bible come to describe Solomon as ruler of a magnificent kingdom? Perhaps because the stories of Solomon were passed down by word of mouth for generations. In the process, they were embroidered.

BIBLE VO (1 Kings 11: 1,3): King Solomon married many foreign women, in addition to Pharaoh's daughter. He had 700 royal wives and 300 concubines.

AMIHAI MAZAR: When we read the biblical tradition concerning Solomon, there is no doubt that the text is exaggerating, to a huge extent, the dimensions of the kingdom, the prosperity, all those gold troves in Jerusalem, et cetera.

The fact that Solomon had 1,000 wives, I mean, there was almost 1,000 people living in Jerusalem in this time, so to have 1,000 wivesâ¦it would be quite difficult.

NARRATOR: So, David and Solomon: great kings or tribal chieftains?

The debate has raged for 40 years. Finally, discoveries at an extraordinary new site may help resolve it. Khirbet Qeiyafa: on the border of ancient Israel and the land of the Philistines, in exactly the place where the Bible says the young King David slew the Philistine giant Goliath.

Here, archaeologist Yossi Garfinkel has been excavating a fortified ancient settlement. Its massive walls are testament to a highly organized workforce.

YOSEF GARFINKEL (Hebrew University of Jerusalem): We have here the city wall of Khirbet Qeiyafa, and we calculate that about 200,000 tons of stone were needed to build the fortification of this city.

NARRATOR: This is no tribal encampment. These massive fortifications seem to be the sign of a political structure far more developed than a highland chiefdom. Other tantalizing clues include the handles of some pottery jugs, which bear thumb imprints, often used as an official state seal.

YOSSI GARFINKEL: You see here a very nice impression. This is a thumb impression made by the potter before the jar went into the kiln to be fired. They were marked so you know they were not private jars but jars that belong to the kingdom.

NARRATOR: Further evidence suggests it was an early Israelite city. Among animal bones found in the rubbish heaps of the settlement, Yossi and his team have noticed an intriguing absence.

YOSSI GARFINKEL: So these are animal bones and you can see these are teeth and part of a mandible. And this is sheep or goat. And in our site, we have only sheep, goats and cattle. We don't have pig bones.

NARRATOR: Philistine settlements are full of pig bones. So could this be a sign that at Qeiyafa, the Israelite taboo on pork was already being observed?

When Yossi and his team had organic remains from the site dated, their excitement grew.

YOSSI GARFINKEL: According to radiocarbon dating, this is from the late 11th, early 10th century B.C. So this is really from the time of King David.

NARRATOR: If Qeiyafa was an Israelite city, it would be the earliest ever found. Another discovery suggests an Israelite site in an even more dramatic way. It was made by a teenager working here on his summer break.

ODED YAIR (Student): When I found it, I thought it was just another piece of pottery. Me and my friend Sanyo were digging up pieces of pottery, lots of them. But among them was this one piece with writing on it, the ostracon.

NARRATOR: The ostracon is a piece of pottery with writing painted on it.

YOSSI GARFINKEL: It was a nice geometric shape. It was quite strange, because usually pottery shard are much smaller and they don't have a geometric shape. Only in the afternoon, when it was washed in water, suddenly we saw that it has inscription on it. And then the question is, what is the language?

NARRATOR: The ostracon is faded and almost illegible.

Before Yossi can decipher it, he has to be able to read it clearly. That means sending it to Greg Bearman, in Santa Barbara, California, who uses a unique imaging technology.

GREG BEARMAN (ANE Image): The reason you're unable to see things on pottery or papyrus or any kind of thing like this is the substrate has somehow gotten faded. It's dark. And so you're looking at a dark background with dark text. It's very hard for the human eye to see. It's, you know, looking for the black cat at midnight situation.

NARRATOR: The photo spectroscopy system takes hundreds of pictures of the ostracon at different wavelengths to find out where the contrast between writing and background is highest.

GREG BEARMAN: Here's an example taken with 365 nanometers. It's blank; it may as well not be anything on there. So this shows that, in this wavelength, the pottery and the ink basically reflect the same amount of light and you don't see anything.

As you go up in wavelength, we're stepping into the blue, and we're now into about 500 nanometers, and you see text is starting to show up.

NARRATOR: By combining and processing photos taken at many different wavelengths, Greg finally arrives at a clear image of the text.

A replica of the ostracon was sent to Bill Schniedewind at U.C.L.A.

WILLIAM SCHNIEDEWIND (University of California, Los Angeles): This is really the most important early alphabetic text that we have. Frequently, when we talk about texts from this time period, there are three letters, four letters, five letters. Here you have five lines!

NARRATOR: The letters are Canaanite, the first alphabetic writing system that would give rise to many others, including Hebrew and our own. But deciphering what the script says is a challenge.

To the ancient writing experts working with Yossi in Jerusalem, they seem to be written in a haphazard way, sometimes upside down, sometimes standing up, sometimes on their sides.

HAGGAI MISGAV (Hebrew University of Jerusalem): The 'a', the aleph, which is the same as the 'a', stands here three times: one on the, one on the legs, the other time on the head, which is the original one, and then on the side.

NARRATOR: Struggling to piece together the words which the letters form, the experts can hardly contain their excitement.

EXPERT: This is definitely a Hebrew word.

Don't do.

NARRATOR: They can make out other Hebrew words too: "eved," worship; "shafat," judge; "nakam," revenge; and "melekh," king.

The writing is Canaanite, but the words are Hebrew.

BILL SCHNIEDEWIND: So it's not quite Hebrew script yet, um, but, eventually, this script will develop into Hebrew.

NARRATOR: It makes the ostracon a historic find, a remarkable testament to the birth of Hebrew writing in the process of being systematized.

HAGGAI MISGAV: I only can say that I hold in my hands the most ancient Hebrew text so far found.

NARRATOR: But what everybody really wants to know is what does it say? That question is not easy to answer.

BILL SCHNIEDEWIND: This is a very difficult inscription. Hebrew was written without vowels. So imagine a poorly preserved, vowel-less text. There's a lot of different ways to read a word. It could be a noun, it could be a verb. It's much more problematic than I think most people realize.

NARRATOR: Haggai Misgav is cautious.

HAGGAI MISGAV: You can say, very carefully, it's a text and not just a list of names.

There are sentences there. And there may be sentences with a judicial or a moral meaning, and that's all.

NARRATOR: The exact meaning of the Qeiyafa ostracon may never be deciphered, but its significance is undeniable. It shows that in Solomon's century, in fortified cities, texts were being copied in a very early version of written Hebrew.

The finds at Qeiyafa suggest a solution to the long running debate about Solomon. Like Hebrew writing, Solomon's Israelite kingdom was in the early stages of its formation, a small kingdom struggling to become a bigger one.

This may make sense of one of the few facts about 10th century B.C. Israel we can be sure of: the Bible notes that five years after Solomon died, an Egyptian army invaded, and Solomon's kingdom was crushed.

BIBLE VO (2 Chronicles 12: 2-3): In the fifth year of King Rehoboam, King Shishak of Egypt marched against Jerusalem with 1,200 chariots, 60,000 horsemen and innumerable troops who came with him from Egypt.

NARRATOR: Many scholars claim the biblical account of Shishak's invasion of Israel is backed up by a giant relief in the ancient Egyptian city of Thebes. Figures containing images of bound captives and city walls represent the places Shishak ransacked.

AMIHAI MAZAR: We can see that this raid was intended to cross the central hill country just north of Jerusalem. No pharaoh before him did this. They always just moved along the coast. That means he, in particular, wanted to reach the area of Jerusalem.

Perhaps the Solomonic kingdom threatened some Egyptian interests in this region.

NARRATOR: If that is the case, Shishak's raid is one last piece of compelling evidence for the rising power of Solomon's kingdom. If ancient Israel was a land of tribal chiefdoms, why would Shishak bother to invade?

Perhaps this was a Sherman's march through the ancient Near East to flatten its upstart kingdoms. And at Khirbet en Nahas, there may be evidence that one of Shishak's targets was copper production in the Dead Sea Rift Valley.

In a cross section of a slag heap, Tom Levy sees layers of slag laid down regularly year after year. But then there is a break.

THOMAS LEVY: And what you see is this disruption in the metal production activity at the end of the 10th century.

NARRATOR: The thin layers suggest a stoppage of work at the smelters. Levy believes this corresponds to the time of Shishak's invasion.

While scholars debate the details of Shishak's campaign, they all agree on one thing.

ISRAEL FINKELSTEIN: To put your hand on the copper supply at that time was really critical. Whoever controlled or tried to monopolize this was in power.

NARRATOR: So were these King Solomon's mines?

THOMAS LEVY: I hope that in our excavations at Khirbet en Nahas we'll ultimately find inscriptions that can tell us about biblical characters, whether they were Edomites or the early Israelite kings like David and Solomon. But that's a hope.

NARRATOR: Perhaps control of the mines changed hands as different kingdoms came into power. Whoever controlled the mines, we know copper from Wadi Feynan was traded throughout the region and probably reached Jerusalem.

AMIHAI MAZAR: I believe that if, one day, we should find the copper objects from the temple in Jerusalem, it will prove to come from this area.

NARRATOR: One thing is certain: the finds at Khirbet en Nahas and Qeiyafa have transformed our image of the mysterious 10th century B.C., Solomon's century. It was a time of walled cities and scribes, of rising kingdoms that could command a flourishing copper industry.

At last, King Solomon's Israel and the mysterious kingdom of Edom are emerging from the shadows, and along with them, the long forgotten metal revolution, which transformed their era.

Broadcast Credits

Quest for Solomon's Mines

- Produced and Directed by

- Graham Townsley

- Co-Produced by

- Jeremy Zipple

- Edited by

- Patty Stern

- DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY

- Yoram Millo

- Music

- Joe Delia

- SOLOISTS

- Jesse Levy, Cello

Gerald Reuter, English Horn

Bob Magnuson, Clarinet - NARRATOR

- Craig Sechler

- Sound Recordists

- Ravid Biran

Johnny Camilo

Ricardo Levi

Paul Mendez

William Knight - Assistant Camera

- Iftah Elran

- ADDITIONAL CAMERA

- Eric Cochran

Gary Grieg

Paul Teverini - Bible readings by

- Sara Krieger

- Animation

- Pixeldust Studios

- LOCATION MANAGER

- Husni Mayouf

- KEY GRIP

- Sami Kattan

- WARDROBE

- Ali Dweik

Marie Schneggenburger - SMELTING EXPERT

- Johnny Imseeh

- LOCATION Production Managers

- Ghassan Salti (Jordan)

Elia Sides (Israel) - Production Manager

- Pamela Jacobson

- PRODUCTION COORDINATORS

- Andrew Grimes

Stefanie Kushner - Post Production Supervisor

- Susan Lach

- Post Production Coordinator

- Megan Nemeh

- Online Editor

- Mark Boszko

- Colorist

- Dave Markun

- Sound Mix

- Jeremy Guyre

- Research

- Johnna Flahive

- Interns

- Martin Berman

Justin Deshields - CAST

- Henry Allen

David Berkenbilt

Ghadeer Odeh

Ahmad Srour

Fadel Al-Awadi - Archival Material

- Peter Harrington Books

Peter Wood Productions

Benjamin Jessup

Getty Image Bank

Corbis

British Library/HIP/Art Resource, NY

DeA Picture Library/Art Resource, NY

Bridgeman-Giraudon/Art Resource, NY

British Library/HIP/Art Resource, NY

Bildarchiv Preussischer Kulturbesitz/Art Resource, NY

Eric Lessing/Art Resource, NY

Reunion des Musees Nationaux/Art Resource, NY

Scala/Art Resource, NY

Werner Forman/Art Resource, NY

WGBH Media Library & Archives - Special Thanks

- Royal Film Commission of Jordan

Department of Antiquities of Jordan

Ken Boydston

MegaVision, Inc.

Equipoise Imaging, LLC

Alina Levy

The National Center for Culture and Arts, Jordan

Rania Kamhawi

Abu Shmais Adeib

Timna Park

Eric Cline

Ron Shaar

Russell B. Adams - Senior Producer, NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC TELEVISION

- Linda Goldman

- Senior Executive Producer, NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC TELEVISION

- John Bredar

- NOVA Series Graphics

- yU + co.

- NOVA Theme Music

- Walter Werzowa

John Luker

Musikvergnuegen, Inc. - Additional NOVA Theme Music

- Ray Loring

Rob Morsberger - Post Production Online Editor

- Spencer Gentry

- Closed Captioning

- The Caption Center

- PUBLICITY

- Eileen Campion

Victoria Louie

Karen Laverty - MARKETING

- Steve Sears

- Researcher

- Kate Becker

- NOVA Administrator

- Kristen Sommerhalter

- Production Coordinator

- Linda Callahan

- PARALEGAL

- Sarah Erlandson

- TALENT RELATIONS

- Scott Kardel, Esq.

Janice Flood - Legal Counsel

- Susan Rosen

- POST PRODUCTION ASSISTANT

- Darcy Forlenza

- Associate Producer Post Production

- Patrick Carey

- Post Production Supervisor

- Regina O'Toole

- Post Production Editor

- Rebecca Nieto

- Post Production Manager

- Nathan Gunner

- COMPLIANCE MANAGER

- Linzy Emery

- DEVELOPMENT PRODUCER

- Pamela Rosenstein

- Supervising Producer

- Stephen Sweigart

- BUSINESS AND PRODUCTION MANAGER

- Jonathan Loewald

- Senior Producer and Project Director, Margret & Hans Rey/Curious George Producer

- Lisa Mirowitz

- Coordinating Producer

- Laurie Cahalane

- Senior Science Editor

- Evan Hadingham

- Senior Series Producer

- Melanie Wallace

- EXECUTIVE PRODUCER

- Howard Swartz

- Managing Director

- Alan Ritsko

- Senior Executive Producer

- Paula S. Apsell

A Production of NOVA and National Geographic Television

© 2010 NGHT, LLC and WGBH Educational Foundation.

All Rights Reserved

- Image credit: (camels) © Courtesy Jeremy Zipple

Participants

- Shmuel Ahituv

- Ben-Gurion University of the Negev

- Greg Bearman

- ANE Image

- Erez Ben-Yosef

- University of California, San Diego

- Israel Finkelstein

- Tel Aviv University

- Yosef Garfinkel

- Hebrew University of Jerusalem

- John Grattan

- Aberystwyth University

- Thomas Higham

- University of Oxford

- Thomas Levy

- University of California, San Diego

- Amihai Mazar

- Hebrew University of Jerusalem

- Haggai Misgav

- Hebrew University of Jerusalem

- Mohammad Najjar

- UCSD Levantine Archaeology Lab

- William Schniedewind

- University of California, Los Angeles

- Oded Yair

- Student

Preview

Full Program | 53:07

Full program available for streaming through

Watch Online

Full program available

Soon