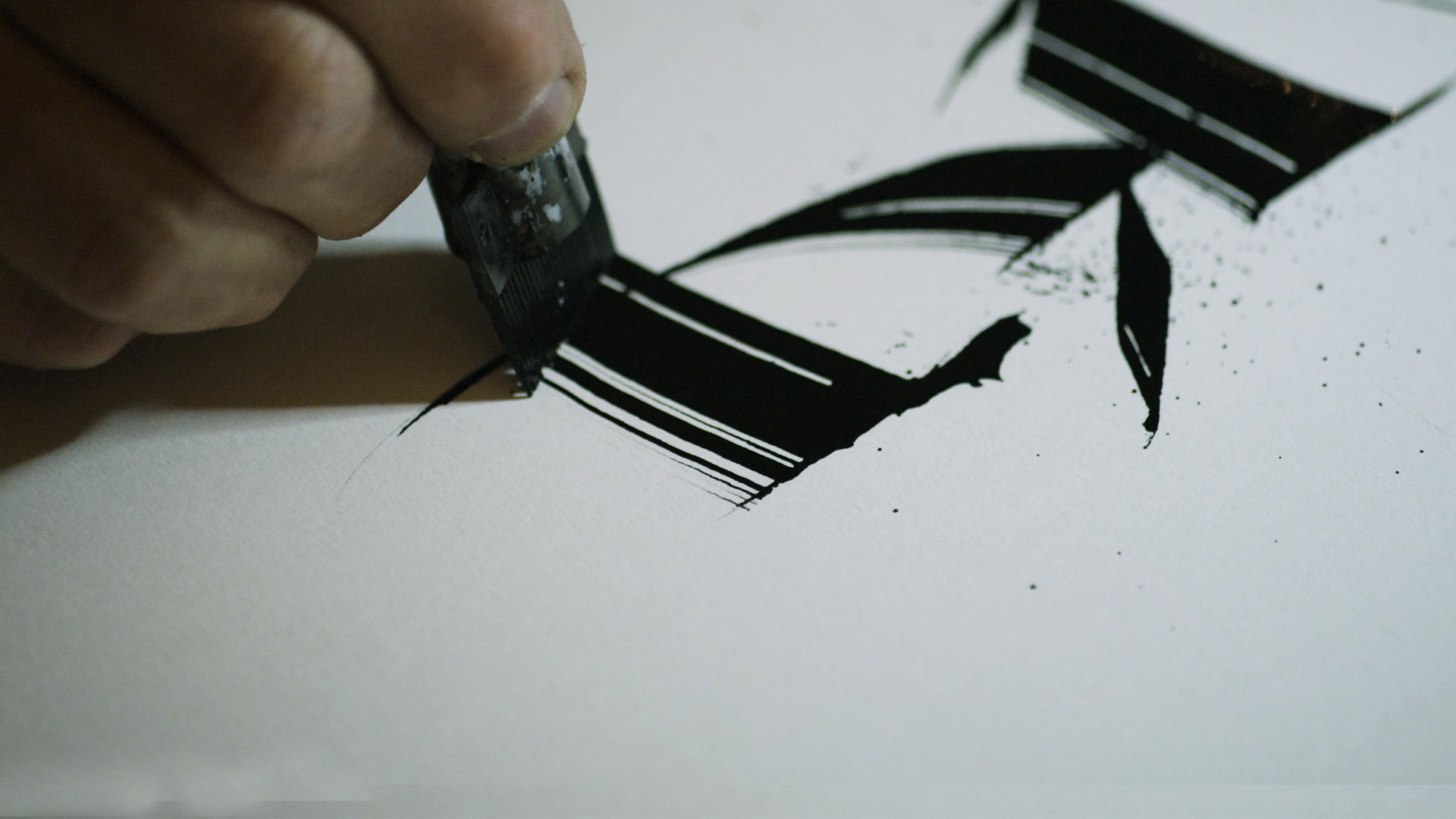

A calligrapher writes with light to keep tradition alive

Equipped with a light and a camera, Karim Jabbari hopes his work can serve as a link between conservative traditional calligraphy and our augmented reality.

Light calligraphy in Australia. Image courtest of Karim Jabbari

Karim Jabbari still remembers how painful it was to walk down the street with his family as a child and see his neighbors turn away. “No one was willing to talk to us in public,” he says. Jabbari’s father was a political prisoner, an activist and “public enemy” of the dictatorship that then ruled Tunisia. His family was under strict police surveillance, and anyone seen talking to them was immediately suspect as well.

Ten-year-old Jabbari, lonely and missing his father, looked for other ways to fill his time. What he found was his father’s trove of 400-year-old religious texts, inherited from an ancestor who had been a renowned scholar of Islam. The books were written in an old form of North African calligraphy known as Maghrebi script. “It’s an art form that speaks to your soul, even if you don’t understand the message,” he says. “I saw the effort of these people spending so much time, writing a thousand pages by hand. I saw the long nights; I saw my father, his smile.”

Before long, he was obsessed, copying what he saw in the books over and over until the arcs and lines settled into his muscles. That obsession only grew once he left his hometown of Kasserine to go to boarding school, and his new skill attracted friends—the one thing he’d never had.

Today, Jabbari, now 42, is a full-time artist based in Canada and the U.S., using murals, graffiti, and specialized technology to bring traditional Arabic calligraphy to an international audience. He worries that a craft that prizes meditative concentration and lengthy training will be lost in an era so focused on agility and speed. His work, he hopes, can serve as a kind of bridge, “a link between conservative traditional calligraphy and our augmented reality.”

Karim Jabbari uses long-exposure photography to capture words written with handheld lights. Image courtesy of Karim Jabbari

Calligraphy—and calligraphers—have resisted new technologies for centuries. For starters, Arabic and its sibling, Persian, used non-Latin alphabets that made them difficult to adapt for use in printing technology developed in the West, says Behrooz Parhami, an engineer who has studied how Arabic and Persian scripts have evolved alongside technology. Physical typefaces built for Persian and Arabic’s connected letters are more fragile, prone to chipping and cracking. And if they aren’t perfectly made, white spaces appear between letters that shouldn’t be there.

The scripts also included letters with elements stacked on top of neighboring letters, which was impossible to recreate using the separate blocks of moveable type. And they varied in height and width much more than Latin characters, meaning that the common printing practice of adjusting typefaces to make letters about the same size would render words illegible. That “would be disastrous,” Parhami says. “It would be very difficult to read.”

It therefore makes sense that in Persia and the Arab world, words simply remained handwritten for centuries longer than in Europe, Parhami says. The printing press spread quickly across Western Europe in the 1460s and 70s, but it would be another 250 years before the Ottomans, who ruled much of the Muslim world, allowed the opening of a print shop. In Persia, it would be nearly 400 years before printing became commonplace. And in modern-day Turkey, authorities eventually resolved the typeface issue in the 1920s by changing that country’s script from Arabic-based to Latin-based.

Karim Jabbari's father's books. Image Courtesy of Karim Jabbari

Still, Parhami attributes this delay not just to the technical challenges but also to the hallowed role of the written word in these societies. In the Arab world, calligraphy provided an intimate connection to God through handwritten copying of the Quran and other religious texts. In the region that now largely constitutes Iran, the related Persian script (which differs by four letters) grew especially elaborate, driven in part by a rich poetry tradition, making the idea of mechanization—and the changes to writing that would come with it—less appealing. Jabbari’s own connection to his ancestors’ books have helped him understand this tension, he says. Arabic calligraphy’s historic link with the Quran makes it a sacred form, he says. It was revered for centuries “and when the printers come, all of that is going to be dumped? That’s hard.”

Although he empathizes, he’s also frustrated to see that same resistance to change in modern Arabic calligraphy’s small, somewhat insular community, which has sometimes been reluctant to embrace innovations like modern fonts, computer-assisted publishing, and social media. Some traditional calligraphers have told him he doesn’t know the “real craft” because he was never able to find a mentor to formally teach him Maghrebi script.

“You can be a beautiful, amazing, well-known, traditional calligraphy artist, but your art isn’t speaking to the younger generations,” he says. Refusing to try new things or embrace new technology leaves young people out, he argues, and puts the entire tradition at risk. "'Your art is dying with you,’ I said to them. I have nothing but respect for you, but I’m taking calligraphy to the streets.”

Although Jabbari also paints murals that incorporate written elements, “taking calligraphy to the streets” usually means light painting: a combination of long-exposure photography and perfectly calibrated movements of a handheld light that captures the loops and swirls of Maghrebi Arabic in thin air. In 2011, after Jabbari’s uncle was shot and killed along with 28 other young men during the beginning of the Arab Spring, he returned to Kasserine to do just such a performance piece. “I wanted to write his name in light painting, the same place where he died,” he says. After he finished honoring his uncle, he gave other families in the area the opportunity to do the same, allowing them to write their loved ones’ names in space—a fleeting memorial fixed on film.

Light calligraphy is a challenging medium. “You need to know the limits of the camera, what space it’s covering,” he says. “You have all of that space to explore, so you end up using your body as reference: making a line at chest level, or one at hip level.” In practice, that looks something like a combination of dance, meditation, and craft.

Jabbari has collaborated with dancers and musicians; he once performed in the background of a symphony orchestra in Abu Dhabi; and he builds yoga into his light calligraphy workshops. He recently hired two software developers to create a program that projects his movements in short near-real-time loops onto skyscrapers, a kind of ephemeral graffiti.

Light calligraphy by Karim Jabbari. Image Credit: Husam AlSayed

Since Jabbari arrived in Canada at 20 years old, calligraphy has become an important way for him to hold onto his culture and identity. “I strongly believe that if you don’t know your history, no one will respect you,” he says. “How can you explain to someone who you are, where you come from, if you don’t know that?”

Calligraphy has taught him that “we are the sum of all the knowledge our ancestors transmitted to one another,” he says. That’s how the art of calligraphy has been passed down—from master to student, who then becomes the next master—and also what calligraphy was for: recording history and wisdom to be shared with the next generation.

Jabbari hopes his work will inspire the traditionalists to try out something new and the modernists to remember the value of tradition, reminding them what writing can be: a form of escape, an adventure in memory. “The problem is, we’re not writing anymore,” he says. “It’s beautiful to evolve, but if you lose the connection with your roots, you get lost.”

In 2013, Karim Jabbari and a group of teenagers from his hometown of Kasserine, Tunisia, worked for over a month to transform a 750-foot-long prison wall into a massive "calligraffiti" mural as part of a project called Towards the Light. Image courtesy of Karim Jabbari

A few months after his performance at the site of his uncle’s death, Jabbari returned at the invitation of Tunisia’s newly formed government to the prison where his father was held toward the end of his 13-year sentence. Jabbari and a team of young men from the city, one of the country’s poorest, worked for 45 days covering its outer wall with an enormous calligraphy mural, the longest in North Africa. The piece, which quotes a verse by the Tunisian poet Chebbi, reminds readers that “life does not await those who are asleep.” It struck him as perfect for the moment when so many Arab societies were rejecting their dictators.

During the Arab Spring, “I saw the birth of a new movement,” he says. In Tunisia, the revolution sparked a renewed interest in “calligraffiti,” which melds traditional calligraphy with a more modern, street-smart “graffiti” style. “This is something really beautiful,” he says. “These are people who are proud of their language. They know what it means to them, as part of their history and heritage, and they’re using it.”