In a first, astronomers find a potential planet outside the Milky Way

The exoplanet candidate is about the size of Saturn and located in a Whirlpool galaxy system 28 million light-years from Earth.

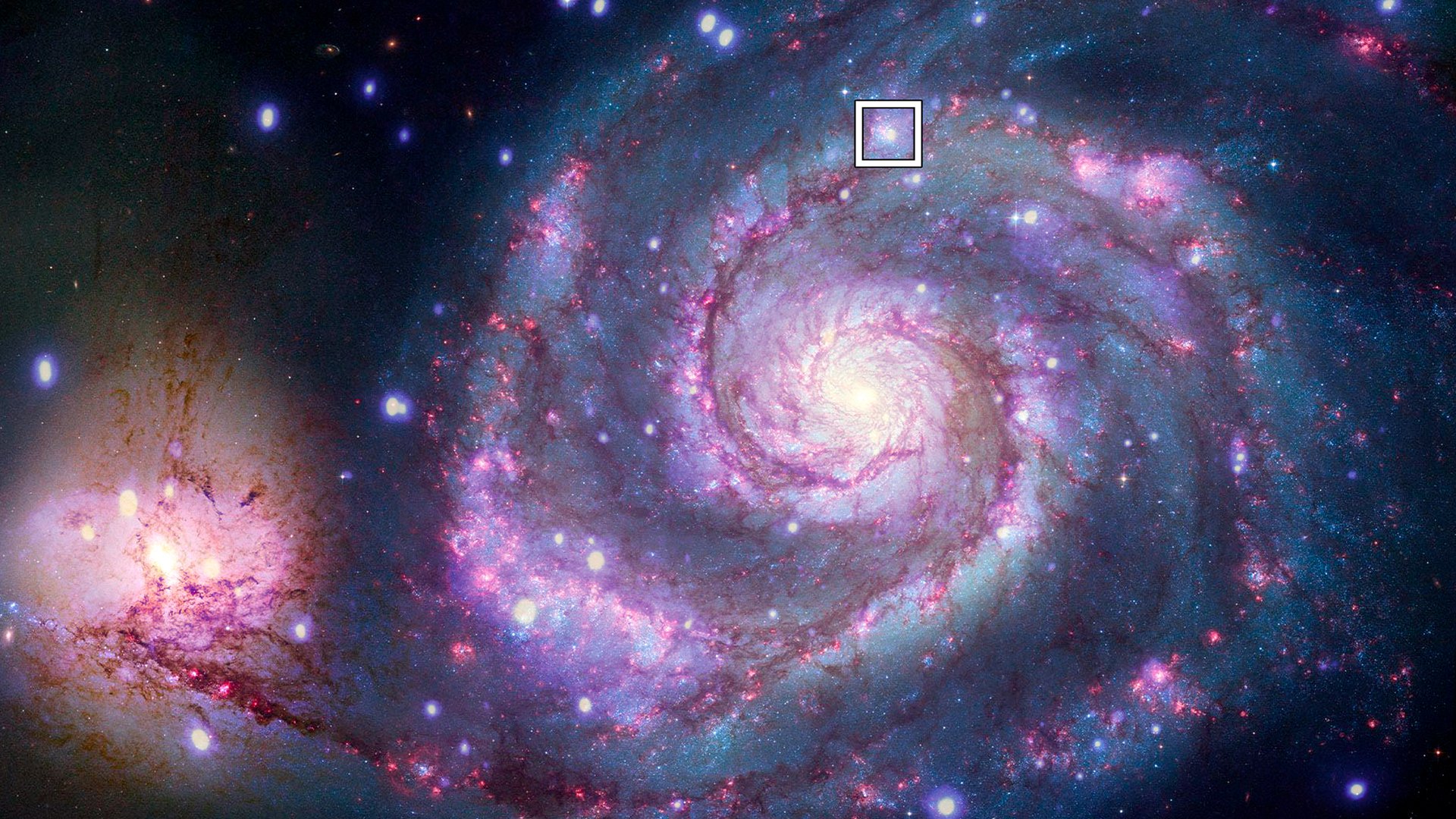

A composite image of M51 with X-rays from Chandra and optical light from NASA's Hubble Space Telescope contains a box that marks the location of the possible planet candidate. Image Credit: X-ray: NASA/CXC/SAO/R. DiStefano, et al.; Optical: NASA/ESA/STScI/Grendler

Within the spiral-shaped M51 galaxy nicknamed “Whirlpool,” 28 million light-years from Earth, a Saturn-sized planet may orbit both a star that resembles our sun and a collapsed one.

If confirmed, the planet would be the first astronomers have spotted outside the Milky Way—millions of light-years farther away than exoplanets astronomers have previously identified—NASA stated in a press release on Monday. The international team of astrophysicists and astronomers responsible for the find, led by Harvard & Smithsonian astrophysicist Rosanne Di Stefano, believe the world is about as far away from its two stars as Uranus is from the sun. They published their findings this week in Nature Astronomy.

An exoplanet is a planet that orbits a star other than our sun. And in the last three decades, scientists have accomplished what once seemed impossible: detect thousands of exoplanets, despite their faintness in the night sky.

“Until now, all other exoplanets have been found in the Milky Way, and most of them have been found less than 3,000 light-years from Earth,” Amy Woodyatt writes for CNN. To spot an exoplanet outside of the Milky Way, the team of researchers set its sights on a system where a sun-like star is in orbit around a neutron star or black hole—a system called an “X-ray binary.” It used NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory to detect the dimming of X-rays from the binary, NASA said in its press release. This dimming, during which the X-ray emission decreased to zero, lasted for about three hours, Linda Geddes reports for The Guardian, helping the team conclude the exoplanet is about the size of Saturn.

This technique, in which scientists record the brightness of distant stars and then look to see if they dim slightly—a sign that a planet may be passing by or “transiting” the star—is called the transit method. From the dip in brightness, astronomers can infer how far a planet may be from its star, the planet’s size, and, by analyzing the starlight that shines through the planet’s atmosphere, Jamie Carter writes for Forbes, gather data about its composition. The transit method “is how most exoplanets are found in our own Milky Way galaxy,” Carter writes.

And it may also be key to hunting down exoplanets outside our galactic neighborhood, scientists believe. "We are trying to open up a whole new arena for finding other worlds by searching for planet candidates at X-ray wavelengths, a strategy that makes it possible to discover them in other galaxies," Di Stefano said in a NASA statement.

But without more data, Di Stefano and her team can’t yet be certain that the object they spotted in the M51 galaxy is indeed an exoplanet. The dimming researchers observed using Chandra could be from a cloud of gas or dust passing by the X-ray source, though that’s unlikely according to their observations, NASA stated in its press release.

The object’s large orbit within its star system will make it challenging to do another assessment. It will take another 70 years for it to cross in front of the X-ray binary again, “and because of the uncertainties about how long it takes to orbit, we wouldn’t know exactly when to look,” study co-author Nia Imara of the University of California at Santa Cruz told NASA.

Illustration of the exoplanet candidate transiting a star outside of the Milky Way. Image Credit: Chandra image gallery, NASA

If the object is a planet, it likely experienced a turbulent past, NASA stated in its press release. In fact, any exoplanet in its binary star system “would have had to survive the cataclysmic supernova explosion that created the neutron star or black hole from a previously existing star,” Geddes writes for the Guardian. The future of the system may be violent, too: The companion star could also explode, blasting any orbiting planets with high levels of radiation, NASA stated.

Di Stefano, Imara, and the rest of their team are also setting their sights on exoplanet candidates in other galaxies, including some that are closer to Earth than M51. Already, they’ve used Chandra and the European Space Agency’s XMM-Newton to peer within 55 systems in M51, 64 in the “Pinwheel” galaxy Messier 101, and 119 in the “Sombrero” galaxy Messier 104, “resulting in the single exoplanet candidate,” NASA stated in its press release.

Study co-author Julia Berndtsson of Princeton University knows the team is “making an exciting and bold claim” by announcing they may have found an extragalactic exoplanet, and that other astronomers will assess their findings very carefully. “We think we have a strong argument and this process is how science works,” she told NASA.