An Unsinkable Ship?

The Titanic made a mockery of the notion, yet naval engineers have devised key innovations to safeguard modern ships.

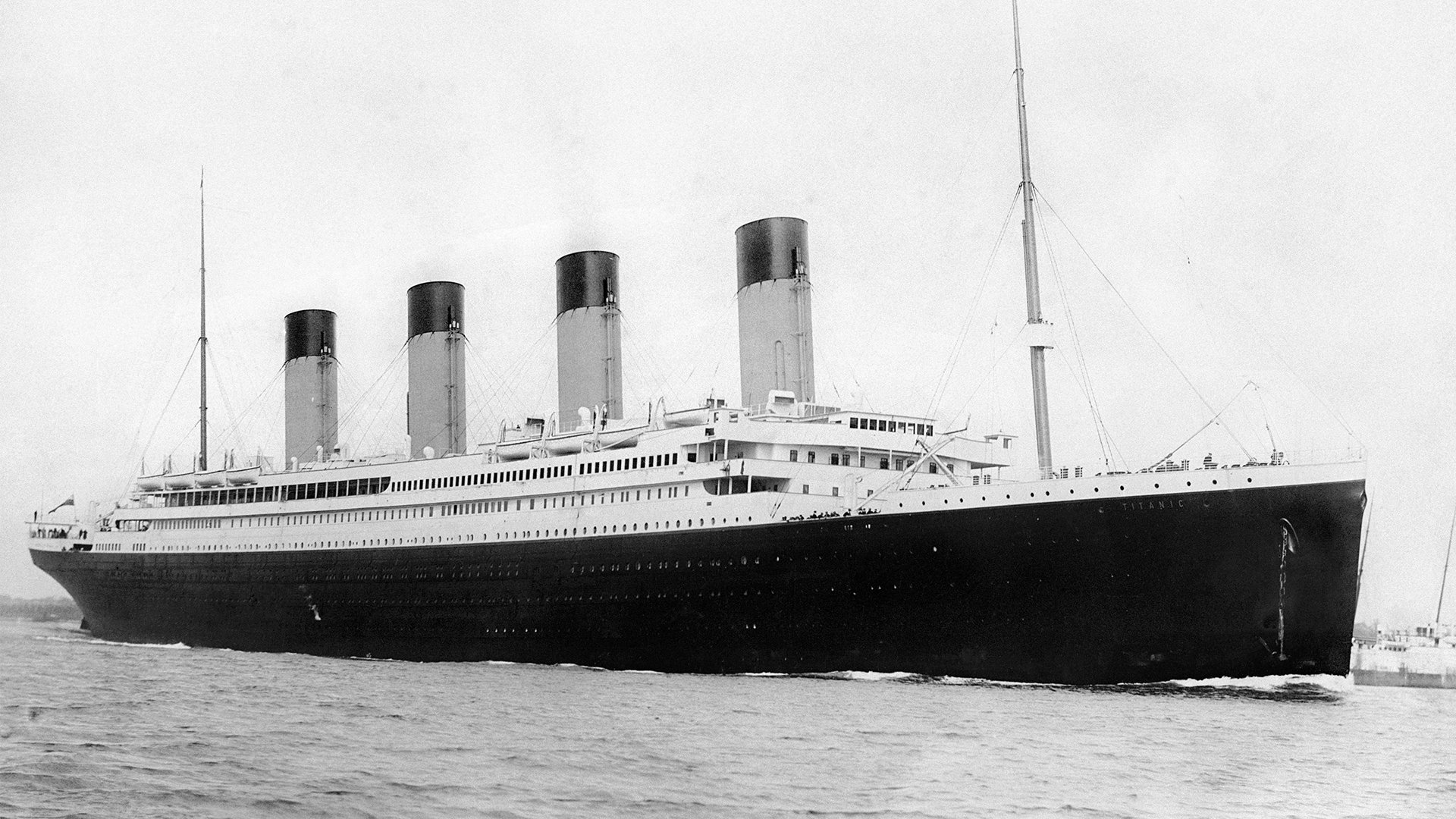

RMS Titanic departing Southampton on 10 April 1912. Image Credit: F.G.O. Stuart

"You can have all the safety in the world and it's not going to help you if you hit a bomb," points out Dr. Robert Ballard, who recently explored the wreck of the ocean liner Britannic, which sank during World War I off the coast of Greece, the victim of either a bomb or a torpedo. The sinking of Britannic was especially tragic—not only because it followed so closely the sinking of its sister ship, Titanic, in 1912, but because extensive safety improvements had been made to the ship to avoid just such a repeat disaster.

While bombings are no longer a daily threat for most ships, danger still lurks in the form of fires, groundings, collisions and worse. So engineers, designers and human systems analysts are continually devising new ways to keep ships where they belong—on, not under, the water.

Recent Innovations

Surprisingly, structural safety design has changed very little since the days of the pre-World War I luxury liners. Modern day cruise ships have more or less the same safety features that the Britannic had. What has changed, however, is the execution of those designs.

For example, both the Britannic and the Titanic had reinforced steel hulls. But recent research suggests the steel might have been of poor quality, making it dangerously brittle under stress. Today, materials engineers use computers to model the stresses on ship hulls and formulate steel able to withstand those stresses.

Watertight compartments, or hull divisions, are another safety feature from the days of the Britannic that have carried over to modern cruise ships. If a puncture occurs, the idea is to contain and isolate the incoming water—and keep the ship afloat until help can arrive. The concept was proved sound when the Olympic, yet another sister ship to Titanic and Britannic, received a 34 foot gash in its hull from a collision at sea. With one of it compartments filled with water, the ship was able to limp back to port.

If disaster does strike, the chances of help arriving in time to minimize casualties are better today than ever before.

"Those were such good innovations that we stay with them," explains Dr. Owen F. Hughes, a naval architect at the Virginia Polytechnic Institute, "We would never do away with them." The newly completed 51,000 ton cruise liner, Carnival Destiny, has 18 watertight compartments. Two can be filled with water and the ship will still float.

This concept of containment has recently been expanded and applied to fire, the most common cause of disaster at sea. "We now require structural fire protection," explains Commander Van Haverbeke of the United States Coast Guard. "The vessel needs to be both subdivided and built of non-combustible material, so if a fire does start in a certain area, the spread is limited." In the days of the Titanic and Britannic, few fire regulations existed at all.

The Human Element

Even the best safety innovations can't keep a ship afloat if the features are used incorrectly—or not at all. Evidence from Dr. Ballard's recent exploration of the Britannic wreck suggests that when disaster struck the ship in the form of a mine or torpedo, the doors that divided the hull into watertight compartments were, for some reason, left open. Also left open were the lower portholes, further defeating the integrity of the hull. Whether closed doors and portholes would have saved the Britannic from sinking is anybody's guess, but as Ballard points out, "You can have all sorts of safety technology, but if some idiot turns the doggone stuff off, so much for design."

From capsizings to groundings of large oil tankers, human error is almost always the culprit behind the worst accidents at sea. In 1987, Britain's Herald of Free Enterprise ferry left port with one of its cargo doors wide open. The ship, known as a "ro-ro," was designed to roll vehicles on one end of the ship and off the other, thereby minimizing time in port. Ironically, the Herald of Free Enterprise was chock-full of sophisticated safety equipment, but none of it addressed the simple possibility of someone forgetting to close the bow door. Water surging across the cargo deck ended up capsizing the ferry in shallow water.

The real trick is keeping boats out of trouble in the first place.

To reduce these types of accidents, the U.S. Coast Guard and other international agencies have begun to focus more and more on the human element in ship safety. Commander Van Haverbeke explains, "One of our primary projects is what we call 'prevention through people'. It's the recognition that the majority of casualties have their root in the human element. Can we make ships safer? Yes. Can we do it all by technology? I think there is a vast area for improvement by focusing on the way people are using the ships they already have and operating them more safely."

Part of this means understanding and accepting a given ship's limitations. For example, the "ro-ro" ferry design is extremely efficient for channel crossings, but is not well suited for transit in heavy seas. This became abundantly clear in 1994, when a huge wave ripped the bow door right off the Estonia near the coast of Finland. The ferry capsized, and eight-hundred and thirty-four passengers were killed. As a result, "ro-ro" ferries are no longer used in heavy weather, and many companies have welded their bow doors permanently shut.

Saving Lives

When the Titanic sank after hitting an iceberg, there weren't enough lifeboats for the number of people on board. By the time the Britannic set sail, two years later, ships were required to carry enough lifeboats to accommodate all on board. This addition helped save the lives of most of those aboard the Britannic. According to Dr. Hughes, lifeboat technology has continued to evolve. "Lifeboats are much easier to launch now. And they've doubled the capacity. So if a ship is heeling and you can only launch boats on one side, you still have enough." New types of evacuation slides are also beginning to be deployed.

If disaster does strike, the chances of help arriving in time to minimize casualties are better today than ever before. Advanced communications and navigation technology allow the Coast Guard and other rescue agencies to pinpoint ships in distress quickly and accurately. According to Commander Van Haverbeke, "We have rapidly cut down on the loss of life due to delays in getting the rescue there."

One ship the Coast Guard uses for rescue missions in severe weather is the remarkable 47-foot Motor Lifeboat, which is about as close to "unsinkable" as any vessel currently at sea. Able to travel at speeds of up to 25 knots through 30-foot surf, the boat carries a small, but extremely hardy crew of four. Not only does the vessel ride high on the water, so much so that its passengers feel every swell—but it can capsize completely, and within eight seconds, return automatically to an upright position. A series of ballast compartments in the hull force the ship to float upright.

"If you get seasick, this isn't the boat for you," laughs Tom Goodearl, former Boatswain's Mate with the U.S. Coast Guard. "It rides like a cork on the waves and really throws you around. You get very wet, but it's exhilarating. It does give you a real feel for how heavy water is and what the ocean can do."

In January of 1996, a tug boat towing a large oil barge off Rhode Island exploded, throwing six crew members overboard in high seas. Much publicity came from the giant oil leak that resulted. But less publicized was the rescue team that went out in the severe weather and saved all six lives using the Motor Lifeboat.

Prevention

While all these innovations help, the real trick is keeping boats out of trouble in the first place. This is perhaps where advanced technology has had the biggest impact. Radar can give ships a visual picture of where they are and what other ships are in the area. Better weather forecasting can guide ships away from hurricanes and severe weather altogether. GPS and other navigation systems can pinpoint a ship's exact location. Iceberg patrols can warn ships out of harm's way. And advanced satellite communications systems can transmit information at sea greater distances than ever before.

So even though there's no such thing as an unsinkable ship, seafarers can rest assured that their chances of making it to shore have improved considerably in recent years.