Julian the TrailblazerPercy Julian was one of the great scientists of the 20th century. In a chemistry career spanning four decades, he made many valuable discoveries, for which he was awarded dozens of patents, 18 honorary degrees, and membership to the prestigious National Academy of Sciences—only the second African-American bestowed such an honor. Yet Julian's achievements as a trailblazer for black chemists, while less well-known, are no less remarkable. Growing up when racial discrimination factored into every aspect of life for blacks in America, from riding a bus to getting a job, Julian persevered to realize his dreams. And when he finally "arrived" as a successful chemist and businessman, he did not lose sight of the challenges that fellow blacks still faced. He became a mentor to scores of young black chemists and, later in life, an inspiration for thousands as a civil-rights leader and speaker. As the late Vernon Jarrett, one of the nation's leading commentators on race relations, put it, "This man is Exhibit A of determination and never giving up. I think he's a role model not only for blacks but for all races." A childhood of racismJulian felt the sting of discrimination early on. Born in 1899, he grew up in Alabama, where two of his grandparents had been slaves and where "Jim Crow" laws of segregation still held sway. Few African-Americans received education beyond the eighth grade, and every day they walked a tightrope in the face of deeply entrenched racism. "You knew that if you said the wrong thing or went in the wrong door or drank out of the wrong water fountain, any of those things could lead to your death," says James Anderson, an historian at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Julian knew this firsthand: when he was 12, he came across a lynched body hanging from a tree. Julian's parents, and Julian himself at a young age, understood that the way out from beneath this smothering blanket of oppression lay through education. Many whites of the day felt that African-Americans only needed enough schooling to become field hands; those few "uppity" blacks who did insist on getting college or graduate degrees should only doctor, teach, or preach to other blacks. Julian had broader ideas. With no high school to attend, he did two years at a teacher training school for African-Americans before, providentially, gaining admittance into predominantly white DePauw University in Indiana. Drastically behind his fellow freshmen academically, Julian went on to graduate Phi Beta Kappa and first in his class four years later. Exhibit A of determination. If he'd been white, Julian could have stepped straight into the doctoral program of his choice. But no graduate school would have him—at least initially. Eventually he got a scholarship to attend Harvard, and he earned a master's degree there, but he left before obtaining his doctorate. It's not entirely clear why, but Anderson suggests one possibility. In those days, the only way that many graduate students financed their education was by becoming teaching assistants. But the idea of blacks teaching whites was as anathema at Harvard as anywhere else in the 1920s. Because of this bias, Anderson says, Julian never got such a position, and his tuition money ran out. In the end, it would take 10 years of Julian's life and even leaving the country to secure his Ph.D. But he finally succeeded, earning his doctorate in chemistry from the University of Vienna in 1931. A topsy-turvy careerOn his return from Vienna that fall things looked more promising for Julian than ever. He returned to Howard University, the country's leading African-American university, where he'd taught before going to Vienna. He was made full professor and chairman of the chemistry department, and he set out to create a center for chemical research. He was now America's foremost black chemist. But Julian got caught up in university politics, and for reasons that, again, remain somewhat obscure, he was forced to resign. He returned to his alma mater, DePauw, as a researcher, soon unable even to teach. His career lay in a shambles. They could only apologize to Julian: "We didn't know you were a Negro." Another man might have given up the struggle and resigned himself to his fate. But Julian, characteristically, did just the opposite. He took on a high-stakes research project that would either secure or destroy his reputation. He set out to synthesize (or create artificially in the lab) an alkaloid called physostigmine, used to treat glaucoma, even though a leading English chemist at Oxford University had already published nine papers on the subject and seemed well on his way to achieving the synthesis. Julian went so far as to state in a paper that the Oxford chemist, Sir Robert Robinson, had made a major error. It was all or nothing—if he was wrong, his career would likely suffer a mortal blow. Julian prevailed. Indeed, chemists around the world recognized his elegant synthesis of physostigmine as a milestone in American chemical history. Again, if he'd been white, universities would have fallen over backwards to get him on their staff. But in those days, traditionally white institutions of higher education would not tolerate having an African-American on their faculties, Anderson says. Industry, to which Julian then turned, was no more enlightened. When DuPont invited Julian and his Austrian colleague Josef Pikl, who had come to the States with him, for interviews, they offered Pikl a job but could only apologize to Julian: "We didn't know you were a Negro." In 1936, the Institute of Paper Chemistry in Appleton, Wisconsin was on the verge of hiring Julian when they realized that an old statute prohibited Negroes from staying overnight in the town. MentorFortunately for Julian, the vice president of Glidden, a manufacturer of paints and other products, sat on the board of the Appleton institute. He had been seeking a talented chemist to run his new research lab in Chicago, and he knew a good thing when he saw it. He promptly hired Julian, who became the first black chemist to direct a chemical research laboratory. It was a coup of almost unprecedented proportions for an African-American in 1936. "The idea that you could break out of that [notion that blacks could only teach and work with blacks] and find a job or a career in some other area was almost completely foreign and unheard of," says James Shoffner, one of many African-Americans whom Julian inspired to become a chemist. "When I saw that here was a person who looked like me who was not only in the field but succeeding magnificently, at the top of his profession, that was profound." Over the next four decades, Julian would hire and train dozens of young black chemists. "As he pointed out to me, it was only natural that when he had control of his own destiny, he would offer this opportunity to fellow black chemists," says Peter Walton, a long-time Julian employee. Julian had what Walton terms a "natural farmland" from which to draw this talent. Having taught at Howard, Fisk, and West Virginia universities, Julian had a network of contacts throughout the black college system that he used to recruit promising African-American chemists. Many of these young scientists used their years with Julian at Glidden, or later at Julian's own company Julian Laboratories, as a springboard to distinguished careers in industry or academia. Civil-rights leaderThe burden of intolerance did not lift for Julian with his hiring at Glidden, of course. Nor, with his success, did he forget the prejudice that other blacks less fortunate than himself continued to endure. Indeed, the older he got, the more proactive Julian became as an advocate of civil rights. He was, said Vernon Jarrett, "a bold but subtle race man." A seminal period for Julian came after he moved his family into the all-white Chicago neighborhood of Oak Park. He soon began receiving death threats, and an arsonist tried to burn down his house. At first, his fury almost got the better of him. His son Percy Julian Jr. recalls sitting evenings in a tree shortly after the arson attack with his father, who cradled a shotgun in his lap. One can envision how suddenly Julian's place in history might have evaporated if those who wanted him gone had returned on one of those nights. "It just knocked me out to see this heralded, international figure doing this one-on-one with these black kids." But Julian's anger cooled—he was, Jarrett said, "steaming on racism, but not against individuals"—and he soon chose avenues more befitting his stature and his nature. He started modestly, joining the fair-housing movement in Oak Park. But soon he began working on a larger canvas, leading a national fundraising campaign for the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund and giving interviews and speeches in which he decried the plight of the black man in America. "Branded, first," Julian railed in one speech, "unfit to spend their money for food or drink in public places along with other Americans; denied the ballot and confined to ghettos that stifled hope and ambition, victims of murder of the mind, heart, and spirit—this is the story of the American Negro." Later in his life, when the civil-rights movement was in full swing, Julian came to understand how younger African-Americans might see him as an accommodationist. By accepting the prevailing notion that if blacks just worked hard enough, they would succeed, rather than rebelling against the bigotry undergirding that sentiment, he and others of his generation might have unwittingly helped perpetuate the white suppression of black talent, he realized. Julian's own hallmarks—a focus on education, the pursuit of excellence, and working within the system (the courts and the legislature) to bring about change—were simply no longer enough. Role modelHis suspicions about himself notwithstanding, Percy Julian's greatest contribution to improving the status of the black man in America may have been serving as an inspiration. He cleared racist hurdles all his life, proving how never giving in could pay off. He broke the color barrier in chemistry a decade before Jackie Robinson did in baseball, and he went on to found his own company and see it thrive. After Percy Julian, Shoffner says, nobody could say with any credibility that blacks couldn't do science. Nor that they couldn't succeed in business: Julian became a millionaire, whom the Chicago Sun-Times once named "Chicagoan of the Year." Above all it was his capacity as a mentor to young black chemists—and, to a lesser but still significant extent, to young blacks in general. Vernon Jarrett recalled a time about five years before Julian's death in 1975 when Julian spoke to about 150 black youth at a local NAACP event in Chicago. The incident offers a snapshot of the man in his prime. "After we concluded," Jarrett remembered, "one or two [kids] came up and wanted to get his autograph because he was a celebrity. And he says, 'No, let's do it this way.' ... He went down the aisle, shaking hands with every single youngster there. ... He wanted to know their names. ... 'What kind of grades are you making in school? Do you like to read? Have you ever heard of Frederick Douglass?' ... [I]t just knocked me out to see this heralded, international figure doing this one-on-one with these black kids."

Exhibit A of determination, ever striving to pass the baton.

|

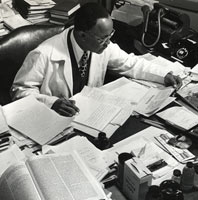

Mentor, father figure, role model: Percy Julian was all these to young blacks, particularly aspiring chemists, in the middle decades of the 20th century.

Julian went from a "sub-freshman"—his term—upon entering DePauw University to valedictorian upon graduation four years later (above).

Even vandalism and threatening letters, including one that read "We will not give up, you and your children will be killed if you do not move," were not enough to intimidate Julian into leaving Oak Park.

To the end of his life, Julian felt passionately about advancing prospects for younger generations of African-Americans. |

|

Peter Tyson is editor in chief of NOVA online. Forgotten Genius Home | Send Feedback | Image Credits | Support NOVA |

© | Created January 2007 |