|

|

|

Digging in Thin Air

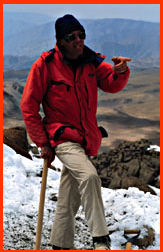

Digging in Thin AirPart 2 (back to Part 1) The Summit You can almost see the curve of the Earth from up here, and it is no wonder that Sara Sara is a huaca, or "sacred place." The route from the high camp up to the excavation site is straight up through small ice pinnacles, boulders, scree, and snow. You can take your pick of which substance you prefer to tread on. Ice axes and ski poles steady your balance, as your backpack often lurches from side to side. Each step takes you higher, and as the days progress it doesn't get easier. The most striking feature of Sara Sara's summit is its varied terrain. The summit is actually a series of summits, extending across some 5 kilometers, punctuated with rock spires, huge sand pinnacles, and Inca rock platforms. The 360-degree view overlooks agricultural villages thousands of feet below, a hint that civilization is just a day or two away. Rivers carve deep canyons and valleys, and a high plateau, called a puna, offers the base for several high volcanic peaks and a line of snow-clad summits like Sara Sara. The view in every direction offers a completely different scene. On the western side, a large alkaline lake, whose name in Quechua means "Flamingo Lake," stretches over several square miles.  The Excavation Site

The Excavation SiteThe clouds and weather come roaring in and out as the archaeological team picks away at the ice and scree. On his first day exploring the summit, Jose Antonio found 4 Inca shawl pins on the surface, 3 in perfect condition and one deteriorated. This indicates that females were most likely sacrificed on the summit. Encouraged by this find, Johan and Jose Antonio set about laying out the site and measuring the key platforms for excavation. Three sites were chosen, one on a high point, where the ground is frozen, another on the north side which is exposed to the sun, and a third within a small, south-facing circle of stones.  It's been 13 years since Johan first climbed Sara Sara. Now he is finally

realising his dream of excavating this peak, which he believes to be among the

most sacred to the Inca. The sound of picks and scraping shovels soon becomes

the mantra of the mountain, as layer after layer of frozen dirt and dense

volcanic rock are dug out. Three strokes of an ice axe and you have to stop

for a long deep breath of what little oxygen is available at 18,000 feet.

Johan oversees the overall operation, picking up an axe here and there and

giving direction to some of the students. His fluent Spanish has enabled him

to work freely with his colleagues and to communicate with the local men from

the nearby village who have joined us. The students, Walter in particular,

often imitate him and repeat words he uses frequently, like "Diablos!," which

means "Devils!" It's "diablos" when a lump in the ice only turns out to be a

sharp stone, and "diablos" when the kerosene lamp in the dining tent goes out.

It's been 13 years since Johan first climbed Sara Sara. Now he is finally

realising his dream of excavating this peak, which he believes to be among the

most sacred to the Inca. The sound of picks and scraping shovels soon becomes

the mantra of the mountain, as layer after layer of frozen dirt and dense

volcanic rock are dug out. Three strokes of an ice axe and you have to stop

for a long deep breath of what little oxygen is available at 18,000 feet.

Johan oversees the overall operation, picking up an axe here and there and

giving direction to some of the students. His fluent Spanish has enabled him

to work freely with his colleagues and to communicate with the local men from

the nearby village who have joined us. The students, Walter in particular,

often imitate him and repeat words he uses frequently, like "Diablos!," which

means "Devils!" It's "diablos" when a lump in the ice only turns out to be a

sharp stone, and "diablos" when the kerosene lamp in the dining tent goes out.

For such hard labour in the bitter cold and altitude, this is one of the happiest groups I've ever worked with. Jokes fly, songs are sung as they work, and never a complaint is heard—perhaps because my Spanish is worse than a one year old's English. Johan, at one point, buried a plastic doll's head for Jose Antonio to uncover. Science here is definitely not always serious. Continue Expedition '96 | Dispatches | Mummies | Lost Worlds | Mail Resources | Site Map | Ice Mummies of the Inca Home | BBC Horizon Editor's Picks | Previous Sites | Join Us/E-mail | TV/Web Schedule About NOVA | Teachers | Site Map | Shop | Jobs | Search | To print PBS Online | NOVA Online | WGBH © | Updated November 2000 |