|

|

|

Lost Empire

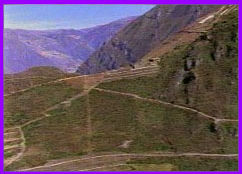

Lost EmpirePart 2 (back to Part 1) The Inca Roads Referred to as an all-weather highway system, the over 14,000 miles of Inca roads were an astonishing and reliable precursor to the advent of the automobile. Communication and transport was efficient and speedy, linking the mountain peoples and lowland desert dwellers with Cuzco. Building materials and ceremonial processions traveled thousands of miles along the roads that still exist in remarkably good condition today. They were built to last and to withstand the extreme natural forces of wind, floods, ice, and drought.  This central nervous system of Inca transport and communication rivaled that of

Rome. A high road crossed the higher regions of the Cordillera from north to

south and another lower north-south road crossed the coastal plains. Shorter

crossroads linked the two main highways together in several places. The

terrain, according to Ciezo de Leon, an early chronicler of Inca culture, was

formidable. By his account, the road system ran "through deep valleys and over

mountains, through piles of snow, quagmires, living rock, along turbulent

rivers; in some places it ran smooth and paved, carefully laid out; in others

over sierras, cut through the rock, with walls skirting the rivers, and steps

and rests through the snow; everywhere it was clean swept and kept free of

rubbish, with lodgings, storehouses, temples to the sun, and posts along the

way."

This central nervous system of Inca transport and communication rivaled that of

Rome. A high road crossed the higher regions of the Cordillera from north to

south and another lower north-south road crossed the coastal plains. Shorter

crossroads linked the two main highways together in several places. The

terrain, according to Ciezo de Leon, an early chronicler of Inca culture, was

formidable. By his account, the road system ran "through deep valleys and over

mountains, through piles of snow, quagmires, living rock, along turbulent

rivers; in some places it ran smooth and paved, carefully laid out; in others

over sierras, cut through the rock, with walls skirting the rivers, and steps

and rests through the snow; everywhere it was clean swept and kept free of

rubbish, with lodgings, storehouses, temples to the sun, and posts along the

way."The Beginning of the End With the arrival from Spain in 1532 of Francisco Pizarro and his entourage of mercenaries or "conquistadors," the Inca empire was seriously threatened for the first time. Duped into meeting with the conquistadors in a "peaceful" gathering, an Inca emperor, Atahualpa, was kidnapped and held for ransom. After paying over $50 million in gold by today's standards, Atahualpa, who was promised to be set free, was strangled to death by the Spaniards who then marched straight for Cuzco and its riches.  Ciezo de Leon, a conquistador himself, wrote of the astonishing surprise the

Spaniards experienced upon reaching Cuzco. As eyewitnesses to the extravagant

and meticulously constructed city of Cuzco, the conquistadors were dumbfounded

to find such a testimony of superior metallurgy and finely tuned architecture.

Temples, edifices, paved roads, and elaborate gardens all shimmered with gold.

By Ciezo de Leon's own observation the extreme riches and expert stone work of

the Inca were beyond belief: "In one of (the) houses, which was the richest,

there was the figure of the sun, very large and made of gold, very ingeniously

worked, and enriched with many precious stones....They had also a garden, the

clods of which were made of pieces of fine gold; and it was artificially sown

with golden maize, the stalks, as well as the leaves and cobs, being of that

metal....Besides all this, they had more than twenty golden (llamas) with their

lambs, and the shepherds with their slings and crooks to watch them, all made

of the same metal. There was a great quantity of jars of gold and silver, set

with emeralds; vases, pots, and all sorts of utensils, all of fine gold....it

seems to me that I have said enough to show what a grand place it was; so I

shall not treat further of the silver work of the chaquira (beads), of the

plumes of gold and other things, which, if I wrote down, I should not be

believed."

Ciezo de Leon, a conquistador himself, wrote of the astonishing surprise the

Spaniards experienced upon reaching Cuzco. As eyewitnesses to the extravagant

and meticulously constructed city of Cuzco, the conquistadors were dumbfounded

to find such a testimony of superior metallurgy and finely tuned architecture.

Temples, edifices, paved roads, and elaborate gardens all shimmered with gold.

By Ciezo de Leon's own observation the extreme riches and expert stone work of

the Inca were beyond belief: "In one of (the) houses, which was the richest,

there was the figure of the sun, very large and made of gold, very ingeniously

worked, and enriched with many precious stones....They had also a garden, the

clods of which were made of pieces of fine gold; and it was artificially sown

with golden maize, the stalks, as well as the leaves and cobs, being of that

metal....Besides all this, they had more than twenty golden (llamas) with their

lambs, and the shepherds with their slings and crooks to watch them, all made

of the same metal. There was a great quantity of jars of gold and silver, set

with emeralds; vases, pots, and all sorts of utensils, all of fine gold....it

seems to me that I have said enough to show what a grand place it was; so I

shall not treat further of the silver work of the chaquira (beads), of the

plumes of gold and other things, which, if I wrote down, I should not be

believed."Continue Expedition '96 | Dispatches | Mummies | Lost Worlds | Mail Resources | Site Map | Ice Mummies of the Inca Home | BBC Horizon Editor's Picks | Previous Sites | Join Us/E-mail | TV/Web Schedule About NOVA | Teachers | Site Map | Shop | Jobs | Search | To print PBS Online | NOVA Online | WGBH © | Updated November 2000 |