|

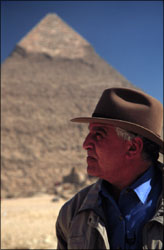

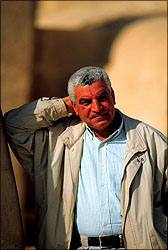

|  Dr. Zahi Hawass before the Khafre Pyramid.

Dr. Zahi Hawass before the Khafre Pyramid.

|

Interview with Dr. Zahi Hawass, Director of the Pyramids

NOVA: Recently your crews unearthed one of the only intact tombs found since

the discovery of King Tut's tomb in the 1920s. What was that like?

Hawass: Very exciting. When I attended the opening of the tomb, it was like

looking at the past and the future. There was a big, six-ton sarcophagus. I had

to ask myself, Is it empty? Is there something? In archaeology, you have to be

a lucky person. If you are unlucky, you can excavate your entire life and

discover nothing. Therefore, when we took off the lid of this sarcophagus and

found inside another five-ton anthropoid sarcophagus, beautifully inscribed,

and underneath that a mummy, it was a moment that no one could really

describe.

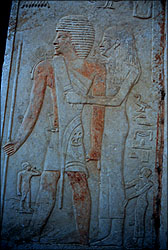

Relief from the tomb of Kai, showing traces of 4,600-year-old paint.

Relief from the tomb of Kai, showing traces of 4,600-year-old paint.

|

| NOVA: You've been excavating the tombs of the Pyramid builders. What have you

found?

Hawass: We've uncovered titles of the craftsmen, draftsmen, tombmakers, the

overseer of the east side of the Pyramid, the overseer of the west side of the

Pyramid, and so on. We found that the average age at death of the workmen was

very early, 30 to 35, while officials died at 50 to 60. We've also studied the

bones in these tombs, which have provided much information. All the skeletons

of men and women show signs of stress in their backs, because people were

involved in moving heavy stuff. We determined through x-rays that someone had

syphilis, and we found evidence of brain surgery on a workman, who lived for

two years afterwards. The ancients even had emergency treatment for workers on

site, because we discovered that they were fixing broken bones and even

amputating legs that had been crushed by a falling stone.

We have unearthed another 65 tombs, the best being that of the priest Kai,

which is dated to the reign of Khufu. It is a beautiful painted tomb with a

unique artistic style. One relief shows Kai's daughter affectionately putting

her arm around his shoulder. At the entrance to the tomb it says that it is the

tombmakers and craftsmen who made his tomb. He says, "I paid them beer and

bread. I made them to make an oath that they were satisfied."

NOVA: Egyptologists often talk about pyramids as "complexes," especially at

Giza. How do the Pyramids integrate with the Sphinx and the temples at Giza?

Hawass: People always look at the Pyramids by themselves, but each lies within

a group of related architectural components, including subsidiary pyramids,

solar-boat pits, a palace, a harbor, workshops, and a funerary temple connected

by a causeway to a valley temple. Together these constituted the physical

elements of the cult of the pharaoh, in which the king was worshipped after his

death. The Sphinx itself is connected to the Pyramid of Khafre.

|  A lone camel driver makes his way home against

Pyramids gilded by a late-afternoon sun.

A lone camel driver makes his way home against

Pyramids gilded by a late-afternoon sun.

|

NOVA: It is difficult to get an inside sense of what life was like during the

Pyramid Age. Can you give us a glimpse of what you've learned about the life of

the pharaohs in Dynastic times?

Hawass: Well, the basic design was for the king to become a god. To achieve

that status, he had to do certain things in his lifetime. He had to build a

tomb, such as a pyramid. He had to erect temples for worshipping the gods, such

as the funerary and valley temples at Giza or the great mortuary temples at

Luxor. He had to "smite his enemies," that is, win victories in battle against

foreigners. And he had to sustain the unification of the two lands, Upper and

Lower Egypt.

Then, after the king's death, he was buried in his tomb. The walls of the tomb

depict scenes to help guide him through the afterlife. A funerary cult

developed, and his followers worshipped him as a deity for years afterward. The

ancient Egyptians believed their kings would live again for all time.

NOVA: Do most Egyptians today feel an ancestral link to the ancient

Egyptians?

Hawass: Of course, because we are the descendants of the pharaohs. If you look

at the faces of the people of Upper Egypt, the relationship between modern and

ancient Egypt is very clear. Habits in the villages, our celebrations when we

finish a project, are similar to what they had in ancient Egypt. After someone

dies, we make a celebration after 40 days, just like the ancient Egyptians did

during the mummification process. Everything in our lives is like ancient

Egypt.

Zahi Hawass

poses with the future gilded capstone.

Zahi Hawass

poses with the future gilded capstone.

|

|

NOVA: What are your plans for celebrating the new millennium at the Pyramids?

Hawass: We are approaching the third millennium A.D., and we're celebrating the

third millennium B.C. If you ask people where they would like to spend the

change of millennium, many would say near the Pyramids, because the Pyramids

have magic and mystery. Many people even dream about the Pyramids!

Our celebration of the millennium will consist of two parts. The first part

will happen December 31st, 1999. Jean-Michel Jarre, the well-known composer, is

designing a party that will extend from sunset to sunrise, through the change

from night to day. Who knows? It could be that something incredible will happen

here. We're also designing a capstone encased in gold, which we'll place on top

of the Great Pyramid by helicopter on that day.

In excavations at Abusir, I discovered two important scenes in blocks. One

scene shows the king and his workmen dragging a capstone; other scenes depict

people dancing and singing. My interpretation is that when the king finished

building the Pyramid, he had his workmen place a capstone sheathed in gold on

top. Then everyone danced and sang—one million individuals celebrating—because the Pyramid was a national project. Every household in every village,

in the north and south, participated in building it. (If you thought today of

building a pyramid, you'd never do it, because you don't have what drove the

Egyptians. Pyramids were built in Eygpt, because the ancient Egyptians made

technology for the afterlife, while we make technology for our life today.)

The second part of the millennium celebration will take place at the beginning

of January. Several years ago, in cooperation with the Germans, we found a

stone inside the Great Pyramid with two copper handles on it. We will send a

robot to see what's behind this door. This will be something that everyone all

over the world will be waiting to find out.

NOVA: Are tourists a danger to the Pyramids and, if so, what are you doing

about it?

Hawass: When tourists enter the Pyramid, they leave behind a lot of water in

their breath. This becomes salt, which can create cracks. We are now removing

this salt mechanically, with ventilation systems, and restoring the cracks. But

to tell you the truth, if I had the power, I would close such things as the

Pyramids and the tombs of Seti, Nefertari, and King Tut at Luxor. These are

things we cannot repeat; we should close them to save them.

|  The Giza Plateau.

The Giza Plateau.

|

We're undertaking a major conservation project on the Giza Plateau. This will

include a ring road around the plateau. All cars will have to use this; none

will be permitted around the Pyramids themselves. We're building a new stable

for camels and horses in the desert to the south of the Pyramids. And we're

demolishing all unnecessary buildings on the plateau, including guard houses,

rest houses, and even my office. Only then can we have the plateau as a sacred,

divine place, where visitors can have private time to enjoy the magic and

mystery.

Soon I will open a site located between Sakkara and Giza called Abusir, which

contains 11 pyramids. They call them the "forgotten pyramids," because no one

knows anything about them. If we open these, then hopefully fewer people will

visit the Great Pyramid, which when it's open is visited by 5,000 people a day,

Egyptians and foreigners.

NOVA: Do you think there's too much excavation and not enough restoration and

conservation?

Hawass: I personally think that excavations should be stopped completely in

Upper Egypt—completely, for ten years. We'll concentrate in Upper Egypt only

in conservation, restoration, epigraphy, photography, and publication. (In the

Delta, on the other hand, you can encourage excavations, because moisture is

quickly deteriorating the monuments.)

Egyptologists have to stop being selfish. I know to get funding you've got to

excavate, but we have to think about future generations, what they will say

about us. UNESCO now is telling everyone that in 200 years these monuments will

be finished because of massive tourism. We have to think about site management

and preservation.

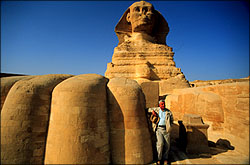

A restored Sphinx dwarfs its chief modern

guardian, Zahi Hawass.

A restored Sphinx dwarfs its chief modern

guardian, Zahi Hawass.

|

|

NOVA: The Sphinx has undergone extensive restoration in recent years. Is it

possible that we run the risk of losing it, and what's being done?

Hawass: When Emile Baraize cleared sand from around the Sphinx in 1926, he

found that the mother rock had completely deteriorated. This is why I say the

Sphinx has cancer. It has suffered a lot from poor restoration, including the

use of cement. Limestone, the rock it's carved from, is like a human being—it needs to breath. When you put cement on it, you stop the limestone's ability

to breath. Recently we did an enormous modern restoration, but it requires

constant vigilance.

NOVA: Do you recommend young people become Egyptologists?

Hawass: I do, I do. I mean, it's the best job in the world! I believe that

Egyptologists have a mission to teach interested young people about working in

the past. Archaeology, after all, is not Indiana Jones. I encourage young

people to study and prepare for the field.

NOVA: Do you think that finding remains of ancient Egypt hidden in the sands

will be ongoing for hundreds of years?

Hawass: I believe that we've only found about 30 percent of Egyptian monuments,

that 70 percent of them still lie buried underneath the ground. You never know

what the sand will hide in the way of secrets.

|  "I would

love to be Khufu!"

"I would

love to be Khufu!"

|

NOVA: Have you ever wished you could have lived during that time?

Hawass: An interviewer once asked me something like, "If you lived in ancient

times, what time would you pick?" And I said, "The time of the Great Pyramid."

Another time, the actor Omar Sharif asked me during the filming of a program,

"If you believe in reincarnation, who would you wish to be?" I said, "If I

believe in reincarnation, I would love to be Khufu!"

Dr. Zahi Hawass is Director of the Pyramids in Giza, Egypt. He is also in

charge of the pyramids at Dashur, Abusir, Saqqara, and the Bahariya Oasis. His

most recent book is The Secrets of the Sphinx: Restoration Past and

Present (American University in Cairo Press, 1998).

Photos: (1,4) Peter Tyson; (2,3,5-7) Aaron Strong.

Pyramids Home | Pyramids | Excavation

Contents | Mail

|