|

MARK LEHNER, Archaeologist, Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, and Harvard Semitic Museum

NOVA: How do we know how old the pyramids are?

LEHNER: It's not a direct approach. There are people coming from a New Age

perspective who want the pyramids to be very old, much older than Egyptologists

are willing to agree. There are people who want them to be built by

extraterrestrials, or inspired by extraterrestrials, or built by a lost

civilization whose records are otherwise unknown to us. And similar ideas are

said about the Sphinx. And in response to the evidence that we have for the

time in which the pyramids are built, the criticism is often leveled at

scholars that they're only dealing with circumstantial information. It's all

just circumstantial. And sometimes we smile at that, because virtually all

information in archaeology is circumstantial. LEHNER: It's not a direct approach. There are people coming from a New Age

perspective who want the pyramids to be very old, much older than Egyptologists

are willing to agree. There are people who want them to be built by

extraterrestrials, or inspired by extraterrestrials, or built by a lost

civilization whose records are otherwise unknown to us. And similar ideas are

said about the Sphinx. And in response to the evidence that we have for the

time in which the pyramids are built, the criticism is often leveled at

scholars that they're only dealing with circumstantial information. It's all

just circumstantial. And sometimes we smile at that, because virtually all

information in archaeology is circumstantial.

Rarely do we have people from thousands of years ago who are writing, who are

signing confessions. So there's no one easy way that we know what the date of

the pyramids happens to be. It's mostly by context. The pyramids are

surrounded by cemeteries of other tombs. In these tombs we find bodies.

Sometimes we find organic materials, like fragments of reed, and wood, wooden

coffins. We find the bones of the people who lived and were buried in these

tombs. All that can be radiocarbon dated, for example. But primarily we date

the pyramids by their position in the development of Egyptian architecture and

material culture over the broad sweep of 3,000 years. So we're not dealing

with any one foothold of factual knowledge at Giza itself. We're dealing with

basically the entirety of Egyptology and Egyptian archaeology.

NOVA: Can you give us an example of a single aspect of material culture, from

ancient Egypt that you might use as a starting point for dating the pyramids?

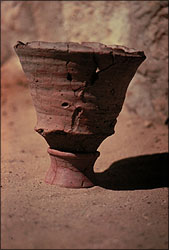

LEHNER: The pottery, for example. All the pottery you find at Giza looks like

the pottery of the time of Khufu, Khafre, and Menkaure, the kings who built

these pyramids in what we call the Fourth Dynasty, the Old Kingdom. We study

the pottery and how it changes over the broad sweep, some 3,000 years. There

are people who are experts in all these different periods of pottery or

Egyptian ceramics. LEHNER: The pottery, for example. All the pottery you find at Giza looks like

the pottery of the time of Khufu, Khafre, and Menkaure, the kings who built

these pyramids in what we call the Fourth Dynasty, the Old Kingdom. We study

the pottery and how it changes over the broad sweep, some 3,000 years. There

are people who are experts in all these different periods of pottery or

Egyptian ceramics.

So to bring it down to a level that almost anybody can understand, if, for

example, you were digging around the base of the Empire State Building,

assuming that it was a ruin and the streets around it in Manhattan were filled

with dirt, and you started finding ceramics that were characteristic of the

Elizabethan era or say the Colonial period here in the United States, that

would be one thing. But if you started finding the Styrofoam cups and the

plastic utensils of the nearby delicatessen, then you would know by virtue of

their position in the overall material culture of the 20th century that that's

probably a good date for the Empire State Building. Of course then you'd look

at the Empire State Building's style and you'd compare it to the Chrysler

Building, and you'd compare it to the Citicorp Building, which is considerably

different. And you'd work out the different styles in the evolution of

Manhattan itself. But by and large, you would, in the broad scope, be able to

put the Empire State Building and Manhattan in an overall context of

development here in the United States and in the modern 19th and 20th

centuries. And you would know that it didn't date, for example, to the

colonial period of George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, because nothing

you'd find in the Empire State Building ruins, around it, in the dirt

surrounding it—maybe it's a stump sticking up above the sloping ruins of

Manhattan—nothing really looks like the flowing blue china, or the other

kinds of utensils and material culture that they used in the time of the

American Revolution. So it's hard to give a succinct answer to that question,

because we date things in archaeology on the basis of its context and a broad

mass of information and material culture—things that were used by people,

styles, and so on.

NOVA: When it comes to carbon dating, do you need organic material?

LEHNER: Right. There has been radiocarbon dating, or carbon-14 dating done

in Egypt obviously before we did our studies, and it's been done on some

material from Giza. For example, the great boat that was found just south of

the Great Pyramid, which we think belongs to Khufu, that was radiocarbon dated—coming out about 2,600 B.C.

NOVA: But how do you carbon date the pyramids themselves when they're made out

of stone, an inorganic material?

LEHNER: We had the idea some years back to radiocarbon date the pyramids

directly. And as you say, you need organic material in order to do carbon-14

dating, because all living creatures, every living thing takes in carbon-14

during its lifetime, and stops taking in carbon-14 when it dies. And then the

carbon-14 starts breaking down at a regular rate. So in effect, you're

counting the carbon-14 in an organic specimen. And by virtue of the rate of

disintegration of carbon-14 atoms and the amount of carbon-14 in a sample, you

can know how old it is. So how do you date the pyramids, because they're made

out of stone and mortar? Well, in the 1980s when I was crawling around on the

pyramids, as I used to like to do and still do, I noticed that contrary to what

many guides tell people, even the stones of the Great Pyramid of Khufu are put

together with great quantities of mortar. We're looking, you see, at the core.

A pyramid is basically, most basically, two separate constructions: it's an

outer shell of very fine polished limestone with great accuracy in its joints,

but most of that's missing; and the other construction is the inner core, which

filled in this shell. Since most of the outer casing is missing what you see

now is the step-like structure of the core. The core was made with a

substantial slop factor, as my friend who is a mechanic likes to say about

certain automobiles. That is, they didn't join the stones very accurately.

You have great spaces between the stones. And you can actually see where the

men were up there and they didn't, you know, they may have like four or five,

even six inches between two stones. And so they'd jam down pebbles and cobbles

and some broken stones, and slop big quantities of gypsum mortar in there. I

noticed that in the interstices between the stones and in this mortar was

embedded organic material, like charcoal, probably from the fire that they used

to heat the gypsum in order to make the mortar. You have to heat raw gypsum in

order to dehydrate it, and then you rehydrate it in order to make the mortar,

like with modern cement.

So it occurred to me that if we could take these small samples, we could radiocarbon

date them, not with conventional radiocarbon dating so much, but

recently there's been a development in carbon-14 dating where they use atomic

accelerators to count the disintegration rate of the carbon-14 atoms, atom by

atom. So you can date extraordinarily small samples. So we set up a program

to do that. And it involved us climbing all over the Old Kingdom pyramids,

including the ones at Giza, taking as much in the way of organic samples as we

could. We weren't damaging the pyramids, because these are tiny little flecks

and it's a very strange experience to be crawling over a monument as big as

Khufu's, looking for a bit of charcoal that might be as big as the fingernail

on your small finger. We noted, not only the samples of charcoal, sometimes

there was reed. Now and then in some of the pyramids we found little bits of

wood. But we saw in many places, even on the giant pyramids of Giza, the first

pyramid and the second pyramid and the third one, fragments of tools, bits of

pottery that are clearly characteristic of the Old Kingdom. And it occurred to

us, you know, these are not just objects, these, the pyramids themselves were

archaeological sites during the time they were being built. If it took 20

years to build them—and now we begin to think that Khufu may have reigned

double the length of time that we traditionally assign him—if people were

building the Great Pyramid over three decades, it was an occupied site as long

as some camp sites that hunters and gatherers occupied that archaeologists dig

out in the desert.

So you see the pyramids are very human monuments. And the evidence of the

people who built them, their material culture is embedded right into the very

fabric of the pyramids. And I think I could take just about any interested

person and show them this kind of material embedded in the pyramids as well as

tool marks in the stones and say, hey, folks, these weren't lasers. These were

chisels and hammers and you know, people who were really out there.

NOVA: What does the radiocarbon dating tell us about the date of the

pyramids?

LEHNER: Well, we did a first run in 1984, actually, funded by the Edgar Cayce

Foundation because they had definite ideas that the pyramids were much older

than Egyptologists believed. That they date as early as 10,500 B.C. Well,

obviously for them it was a good test case because radio carbon dating does not

give you pinpoint accuracy. If you have a plus or minus factor, but I say it's

kind of like shooting at a fly on a barn with a shotgun. Well, you're not

going to hit the fly exactly, you're going to know which side of the barn,

which end of the barn, you know, the buckshot is scattering. And it wasn't

scattering at 10,500 B.C. on that first run of some 70 samples from a whole

selection of pyramids of the Old Kingdom. But it was significantly older than

Egyptologists believed. We were getting dates from the 1984 study that were on

the average 374 years too old for the Cambridge Ancient History, (the Cambridge

Ancient History is a reference) dates for the kings who built these monuments.

So just recently we took some 300 samples, and in collaboration with our

Egyptian colleagues, we are now in the process of dating these samples. The

outcome we are going to announce jointly in tandem with our Egyptian

colleagues, and maybe we can pick up the subject of the results when we're over

there in Egypt together with Dr. Zahi Hawass (during the February excavation of

the bakeries at Giza).

NOVA: Is there any evidence at all that an ancient civilization predating the

civilization of Khufu, Khafre and Menkaure was there?

LEHNER: It's a good question. If they were there, you see—civilizations

don't disappear without a trace. If archaeologists can go out and dig up a

campsite of hunters and gatherers that was occupied 15,000 years ago, there's

no way there could have been a complex civilization at a place like Giza or

anywhere in the Nile Valley and they didn't leave a trace, because people eat,

people poop, people leave their garbage around, and they leave their traces,

they leave the traces of humanity.

Now at Giza, I should tell people how this has come down to me personally.

Because I actually went over there with my own notions of lost civilizations,

older civilizations from Edgar Cayce. When I worked at the Sphinx over a five-year

period we were mapping every nook and cranny, every block and stone, and

actually every fissure and crack as well. And I, on a couple of different

occasions was able to excavate natural solution cavities in the limestone from

which the Sphinx is made. Natural solution cavities are like holes in Swiss

cheese. When the limestone formed from sea sediments 50 million years ago

there were bubbles and holes and so on, and fissures later developed from

tectonic forces cracking the limestone. So for example, right at the hind paw

of the Great Sphinx on the north side, this main fissure that cuts through the

whole body of the Sphinx and then through the floor opens up to about 30

centimeters wide and about a meter or more in length. And in tandem with Zahi

Hawass in 1979-'80, we were clearing out this fissure, which now is totally

filled with debris again. But we actually reached down to our armpits, lying

on our sides on the floor, scooping out this clay. And in the clay was

embedded, not only charcoal, but bits of pottery that were very characteristic

of the pottery that was used during the time of Khufu, Khafre and Menkaure, the

4th Dynasty. Now at Giza, I should tell people how this has come down to me personally.

Because I actually went over there with my own notions of lost civilizations,

older civilizations from Edgar Cayce. When I worked at the Sphinx over a five-year

period we were mapping every nook and cranny, every block and stone, and

actually every fissure and crack as well. And I, on a couple of different

occasions was able to excavate natural solution cavities in the limestone from

which the Sphinx is made. Natural solution cavities are like holes in Swiss

cheese. When the limestone formed from sea sediments 50 million years ago

there were bubbles and holes and so on, and fissures later developed from

tectonic forces cracking the limestone. So for example, right at the hind paw

of the Great Sphinx on the north side, this main fissure that cuts through the

whole body of the Sphinx and then through the floor opens up to about 30

centimeters wide and about a meter or more in length. And in tandem with Zahi

Hawass in 1979-'80, we were clearing out this fissure, which now is totally

filled with debris again. But we actually reached down to our armpits, lying

on our sides on the floor, scooping out this clay. And in the clay was

embedded, not only charcoal, but bits of pottery that were very characteristic

of the pottery that was used during the time of Khufu, Khafre and Menkaure, the

4th Dynasty.

We did that again on the floor of the Sphinx temple which is built on a lower

terrace directly below the paws of the Sphinx. Directly in front of the

Sphinx, we found a solution cavity in 1978, during what's called the SRI

Project, which has been written about. We actually cleared out this cavity.

We found dolomite pounders, these round balls of hard dolomite that are

characteristic hammerstones of the age of the pyramids that they used for

roughing out work in stone. Beyond that, Zahi and I excavated deposits on the

floor of the Sphinx, even more substantial, deposits that were sealed by an

18th Dynasty temple, built by Tutankamen's great grandfather when the Sphinx

was already 1,200 years old. But it was built by a pharaoh named Amenhotep II

and his son, Thelmos IV. They put the foundation of this temple right over

deposits of the Old Kingdom, and sealed it, so that they were left there and

were not cleared away by earlier excavators in our era in the 1930s. We did that again on the floor of the Sphinx temple which is built on a lower

terrace directly below the paws of the Sphinx. Directly in front of the

Sphinx, we found a solution cavity in 1978, during what's called the SRI

Project, which has been written about. We actually cleared out this cavity.

We found dolomite pounders, these round balls of hard dolomite that are

characteristic hammerstones of the age of the pyramids that they used for

roughing out work in stone. Beyond that, Zahi and I excavated deposits on the

floor of the Sphinx, even more substantial, deposits that were sealed by an

18th Dynasty temple, built by Tutankamen's great grandfather when the Sphinx

was already 1,200 years old. But it was built by a pharaoh named Amenhotep II

and his son, Thelmos IV. They put the foundation of this temple right over

deposits of the Old Kingdom, and sealed it, so that they were left there and

were not cleared away by earlier excavators in our era in the 1930s.

Zahi and I sort of did a stratographic dissection of these ancient deposits.

That is we did very careful trenches, recorded the layers and the different

kinds of material. The bottom material sealed by a temple built by

Tutankamen's great or great great grandfather, was Old Kingdom construction

debris. They stopped work cutting the outlines of the Sphinx ditch—the

Sphinx sits down in this ditch or sanctuary. We were able to show exactly

where they stopped work. They didn't quite finish that. We found tools, we

found pottery, characteristic of the Old Kingdom time of Khufu, Khafre, and

Menkaure.

Now the point is this. That it's not just this crevice or that nook and cranny

or that deposit underneath this temple, but all over Giza, you find this kind

of material. And as I say in looking for our carbon-14 samples, climbing in

the pyramids you find the same material embedded in the very fabric of the

pyramids, in the mortar bonding the stones together. So back to the question,

is there an earlier civilization? Well, as I say to New Age critics, show me

one pot shard of that earlier civilization. Because the only way they could

have existed is if they actually got out with whisk brooms, scoop shovels and

little spoons and cleared out every single trace of their daily lives, their

utensils, their pottery, their wood, their tools and so on, and that's just

totally improbable. Well, it's not impossible, but it has a very, very low

level of probability, that there was an older civilization there.

Photos: (1,4,5) Aaron Strong; (2) From "This Old Pyramid"; (3) Carl Andrews

Pyramids Home | Pyramids | Excavation

Contents | Mail

|