|

|

We're all armchair travelers when it comes to Mars, but fortunately a number of

spacecraft bearing sophisticated cameras have orbited and even landed on the

planet over the past three decades. These spacecraft have provided a steady

stream of breathtaking images of the martian surface that, as you'll see in

this sampler slide show, are the next best thing to being there. To see the

images to full effect, please click on each image to enlarge it. You may

also want to resize the resulting popup window to fill the screen. Unless

otherwise noted, all images were taken by the Mars Global Surveyor's Mars

Orbiter Camera. For the latest images from the Phoenix lander, see the Phoenix Mars Mission Web site. For links to thousands of additional Mars images, see Links

& Books.—Peter Tyson

|

|

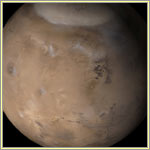

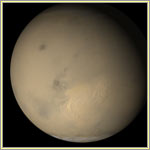

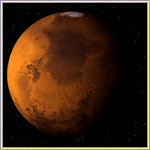

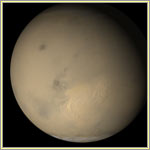

The Planet

This is Mars as it appeared in May 2002. It's early spring in the Northern

Hemisphere, whose seasonal carbon-dioxide frost cap has begun its annual

retreat. Other white areas in this composite are clouds, some seen hovering

over volcanoes such as Olympus Mons, the dark round spot in the far left of

the image. The huge canyon system known as Valles Marineris is visible as a

thick horizontal line in the lower right. All told, Mars is about 4,200 miles

in diameter, a little over half as big across as the Earth.

|

|

|

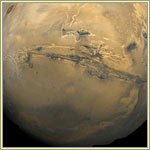

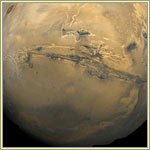

Canyon

In the center of this mosaic of Mars lies the Valles Marineris, the largest

known chasm in the solar system. It stretches over 1,860 miles from west to

east, and in places reaches five miles in depth. (The Grand Canyon, at its

deepest, is just over a mile from rim to river.) Huge rivers once flowed north

from the chasm's north-central canyons to a vast basin called Acidalia Planitia

(the dark area in the top right of the image). To the west of the Valles

Marineris you can see three ancient volcanoes (dark brown circles), each about

15 miles high. This mosaic consists of 102 images from the Viking Orbiter, and

the viewer's distance is 1,550 miles above the surface.

|

|

|

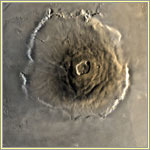

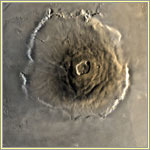

Volcano

This mosaic of images taken by Viking 1 on June 22, 1978, shows Olympus Mons,

the highest known volcano in the solar system. Its summit caldera lies over

78,500 feet above the surrounding plains, making it over two and a half times

the height of Mt. Everest. The volcano proper, defined by the roughly circular

cone visible in the center of the image, is about 340 miles in diameter,

revealing just how gradual a slope the mountain's flanks display. Encircling

the volcano is a moat of lava thought to have come from Olympus Mons.

|

|

|

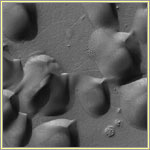

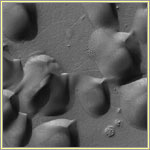

Sand Dunes

Resembling a group of horseshoe crabs coming ashore, windblown sand

dunes grace the floor of Wirtz Crater. The shape of the dunes indicates that

the wind has blown the sand from the southwest toward the northeast (lower left

to upper right in the image). Illuminated by sunlight streaming in from the

northwest, the scene comprises an area less than two miles in width.

|

|

|

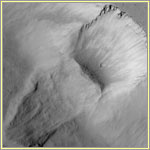

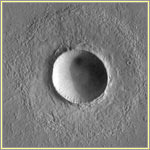

Crater

Looking like it might have been blasted out yesterday, this impressive meteor

impact crater lies in the northern Elysium Planitia, the second largest

volcanic region on Mars. The crater's diameter is a little over twice that of

Meteor Crater in Arizona (which is three quarters of a mile wide and our

planet's best preserved impact crater). Darkening more than half the crater,

the shadow gives an idea of just how deep the basin is.

|

|

|

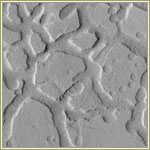

Ice Cap

Dubbed martian "Swiss cheese," these raised sections of ice in the south polar

ice cap and the circular depressions within them may be a combination of water

ice and frozen carbon dioxide, or "dry ice." The area covered in this image is

1.9 by 5.6 miles, and the tallest portions of the raised ice mesas are about 14

feet high.

|

|

|

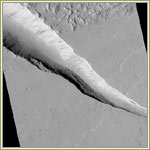

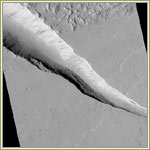

Faulting

The deep trough slashing diagonally across the center of this image resulted

from faulting and down-dropping of the land. Boulders the size of small

buildings can be seen on the slopes of this depression, which is sunlit from

the left. Dark streaks on the trough's slopes are the paths of small

landslides. This trough and the shallower one in the lower part of the image

cut across lava flows, suggesting that the trenches formed after the lava had

cooled and hardened. Short, parallel ridges in the valley floors are probably

dunes.

|

|

|

Layered Rocks

Water or wind deposited the sediments that are thought to make up these layered

rock outcroppings. Wind later shaped and exposed the layers, which on close

inspection resemble those on a topographical map. Note the dark drifts of sand

in the lower center of the image, which is illuminated by sunlight coming from

the upper left. The scene is in the bottom of an impact crater near the martian

equator.

|

|

|

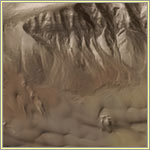

Gullies

Not dramatically different from a mountainside in, say, the American Southwest,

this weathered wall of a crater displays gullies that might have been carved by

groundwater flowing downhill. Wintertime frost dusts the wall, while below on

the crater floor you can see dunes sculpted by the wind. The Mars Global

Surveyor's narrow-angle camera took the shot, which was then "colorized" using

actual colors of the surface obtained by the spacecraft's wide-angle

cameras.

|

|

|

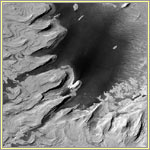

Clouds

One early martian afternoon in April 1999, the Mars Orbiter Camera (MOC)

captured this view of diaphanous clouds floating over the summit of Apollinaris

Patera, a volcano near the planet's equator. The various impact craters

pockmarking its crater and flanks indicate how ancient the volcano is. It is

also enormous: an estimated three miles high, its summit caldera alone is about

50 miles across. The color in this image was derived from the MOC's red and

blue wide-angle camera systems and does not represent true color as you would

see it with the naked eye.

|

|

|

Mesas

To some viewers, the spaghetti-like forms captured in this image may at first

glance appear raised from the surface, but they are actually troughs separating

layered mesas. Pitting and erosion fashioned the mesas, which are lit by the

sun from the lower left. Dust cloaks the landscape, and large, wind-crafted

ripples can be seen on the trough floors. The image is slightly less than two

miles wide.

|

|

|

Landslide

Sometime in the distant past, a large portion of this slope in the Kasei Valles

region gave way and slid down into the valley below. Scientists know it was a

long time ago because of the impact craters apparent in both the landslide's

scar and its resulting deposit. At the base of the scar, just below the

slightly oval-shaped impact crater, you can see numerous black dots. These are

house-sized boulders that have tumbled down from higher up the 660-foot slope.

Near the cornice, you can just make out layers in the bedrock revealed by the

landslide.

|

|

|

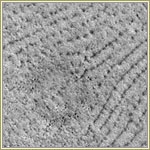

Plains

Like certain high-latitude areas in the Northern Hemisphere on Earth, the

northern plains of Mars often show patterned ground. Whether this stippled

surface indicates ground ice, as similar-looking surfaces do in parts of

Alaska, Canada, and Siberia, is unknown. In this image, taken at a latitude of

72.4°N, the dark dots and lines are low mounds and chains of mounds,

respectively. Note the buried impact crater in the center of the image, which

is about 1.9 miles across.

|

|

|

Dust Storms

In late June 2001, as the martian southern winter gave way to spring, dust

storms began to kick up as cold air from the south polar ice cap moved north

toward warmer air at the equator. By early July, dust storms had cropped up all

over the planet, whose surface, by the end of the month, had become almost

entirely obscured, as if by a single, global storm. By

late September, the storms had largely abated, though the atmosphere remained

hazy into November.

|

|

|

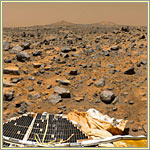

Terrain

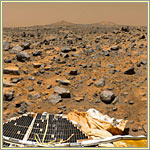

Mars Pathfinder's stereo imaging system took a series of photographs that were

used to create this 360-degree "geometrically improved, color-enhanced"

panorama of the surface of Mars. The images were made over the course of three

martian days to ensure consistent lighting and shadows across the panorama. In

the lower portion of the image, you can see the lander, with its opened petals,

deflated airbags, and pair of ramps. The Sojourner rover descended the rear

(right) ramp to the surface, then made its way to the large rock, dubbed

"Yogi," where it is using its Alpha Proton X-Ray Spectrometer to study the

rock's composition. The "Twin Peaks" visible on the horizon are less than a

mile and a quarter away.

|

|

|

Frozen Water

Use the slider (in enlarged version) to compare these two color images from the Phoenix Mars Lander, which touched down on the Red Planet on May 25, 2008. The lander's Surface Stereo Imager took these pictures on June 15 and June 19, respectively. The pictures show sublimation—the passing of a substance, in this case ice, directly from a solid to a gas—in a lander-dug trench over the course of four days. In the lower left of the lefthand image, a group of white lumps is visible within the shadow; in the righthand image, they're gone. Look closely also at the white patches in full sun—other loss of ice can be seen there. These images confirmed the presence of water ice in the subsoil of the martian arctic.

|

|

|

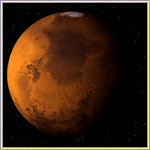

The Planet, Again

This QuickTime VR, or full-round panorama, was created from a photo-mosaic of images captured over a

five-year period by the Viking orbiters in the 1970s. The smooth areas of the globe

are geologically younger than the cratered areas, which are ancient. In places, cliffs

of up to a mile and a quarter in height separate the two areas. Some Mars experts

speculate that water may have once covered the Northern Hemisphere, which is smoother

and younger than the Southern. Note bright and dark streaks on the martian surface;

these point to active wind processes on Mars.

1.3MB; requires free QuickTime plugin software

|

Images: (the planet, terrain) © NASA/JPL; (canyon) © NASA/NSSDC, Viking Orbiter; (volcano) © NASA/NSSDC, Viking 1; (sand dunes, crater, ice cap, faulting, layered rocks, gullies, clouds, mesas, landslide, plains, dust storms) © NASA/JPL/MSSS; (frozen water) Courtesy NASA/JPL-Caltech/University of Arizona/Texas A&M University; (Mars globe) © NASA/USGS

|

|