We recommend you visit the interactive version. The text to the right is provided for printing purposes.

|

Natural epidemics of cholera and plague are frightening enough. The notion that rogue states or terrorists could harness these and other diseases as weapons of war is even more chilling. While rare, the use of biological weapons dates back centuries. Here, explore confirmed cases of biowarfare and bioterrorism, from medieval times to today, and learn more about state-sponsored programs that could provide the seeds of future attacks.—Susan K. Lewis

|

|

Medieval Siege

In the 14th and 15th centuries, little was known about how germs cause disease. Medical practitioners suspected, however, that the stench of rotting bodies could spread illness. So when combatants used corpses as ammunition, these bodies were no doubt intended as biological weapons. Historians know of at least three cases:

1340 - Attackers hurled dead horses and other animals by catapult at the castle of Thun L'Eveque in what is now northern France. The defenders reported that "the stink and the air were so abominable ... they could not long endure" and negotiated a truce.

1346 - As Tartars launched a siege upon Caffa, a port on the Black Sea, they suffered an outbreak of plague. Before retreating, they flung the infected bodies of their comrades over the walls of the city. Fleeing residents carried the disease to Italy, helping to spark the second major epidemic of "Black Death" in Europe.

1422 - At Karlstein in Bohemia, attacking forces launched the decaying cadavers of men killed in battle over the castle walls. They also stockpiled animal manure in the hope of spreading illness. Yet the defense held fast, and the siege was abandoned after five months.

|

|

|

American Revolution

The British military routinely inoculated its own troops against smallpox, exposing soldiers to the pus from smallpox pustules to induce mild cases of the disease and, once the soldiers recovered, lifelong immunity. In Boston, and perhaps also Quebec, the British also appear to have forced smallpox on civilians, hoping to spread disease to rebel troops.

In Boston the mission seems to have failed; infected civilians were quarantined and kept from Continental soldiers. But in Quebec, smallpox swept through the Continental Army, helping to prompt a retreat.

Earlier in the century, the British similarly targeted Native Americans. In an infamous case of 1763, at Fort Pitt on the Pennsylvania frontier, Gen. Jeffery Amherst (pictured at left) ordered that blankets and handkerchiefs from smallpox patients in the fort's infirmary be given to Delaware Indians at a peace-making parley.

|

|

|

World War I

By the time of The Great War, scientists understood how microbes such as bacteria convey disease. The German military applied this knowledge during the war in a widespread campaign of biological sabotage.

Their target was livestock—the horses, mules, sheep, and cattle being shipped from neutral countries to the Allies. By infecting just a few animals, through needle injection and pouring bacteria cultures on animal feed, German operatives tried to spark epidemics of glanders and anthrax, diseases known to ravage populations of grazing animals.

Secret agents waged this campaign in Romania and the U.S. in 1915-1916, in Argentina in roughly 1916-1918, and in Spain and Norway (dates and details are obscure). Despite the claims of some agents, their overall impact on the war was negligible.

The much more apparent horrors of chemical warfare, employing toxins such as mustard gas, led to the Geneva Protocol of 1925. (In this image, a French soldier and his dog are suited up for protection against gas attacks.) The Geneva Protocol prohibited the use of chemical and biological agents, but not research and development. The U.S. signed the Protocol, yet 50 years passed before the U.S. Senate voted to ratify it. Japan also refused to ratify the agreement in 1925.

|

|

|

World War II

The Japanese military practiced biowarfare on a mass scale in the years leading up to and throughout World War II. Directed against China, the onslaught was spearheaded by a notorious division of the Imperial Army called Unit 731.

In occupied Manchuria, starting around 1936, Japanese scientists used scores of Chinese subjects to test the lethality of various disease agents, including anthrax, cholera, typhoid, and plague. These experiments killed as many as 10,000 people.

In active military campaigns, several hundred thousand people—mostly Chinese civilians—fell victim. In October 1940, the Japanese dropped paper bags filled with plague-infested fleas over the cities of Ningbo and Quzhou in Zhejiang province, as well as introduced plague-infested rats. (The image at left allegedly shows Japanese scientists injecting rats with pathogens.) Other attacks involved contaminating wells and distributing poisoned foods. The Japanese army never succeeded, though, in producing advanced biological munitions, such as pathogen-laced bombs.

As the leaders of Unit 731 saw Japan's defeat on the horizon, they burned their records, destroyed their facilities, and fled to Tokyo. Later, in the hands of U.S. forces, they brokered a deal, offering details of their work in exchange for immunity to war-crimes prosecution.

By the end of WWII, the Americans and Soviets were far along on their own paths in developing biological weapons.

|

|

|

Cold War

Bioweapons programs in the Soviet Union and the U.S. flourished in the anxious climate of the Cold War. (At left is a scene from one of the U.S. Army labs at Fort Detrick, Maryland.) Both nations explored the use of dozens of different bacteria, viruses, and other biological toxins. They also devised sophisticated ways to disperse these agents in fine-mist aerosols, to package them in bombs, and to launch them on missiles.

In 1969, the U.S. military conducted a massive field test in the Pacific. The war game—involving a fleet of ships, caged animals, and the release of lethal agents—proved the effectiveness of the U.S. bioweapons. Little did the U.S. team know, however, that Soviet spies were in nearby waters, collecting samples of the agents tested.

At the end of 1969, President Richard Nixon terminated the offensive biological warfare program and ordered all stockpiled weapons destroyed. His decision hinged on a calculation that continuing an offensive program encouraged other nations to do the same, and was therefore, on balance, a security risk. From this point on, U.S. researchers switched their focus to defensive measures, such as developing "air-sniffing" detectors.

In 1972, the U.S. and more than 100 nations signed the Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention, the world's first treaty banning an entire class of weapons. The treaty barred possession of deadly biological agents except for defensive research. Yet no clear mechanisms to enforce the treaty existed. Just as it signed the treaty, the Soviet Union fired up its offensive program.

|

|

|

Soviet "Superbugs"

In 1979, a rare outbreak of anthrax disease in the city of Sverdlovsk killed nearly 70 people. The Soviet government publicly blamed contaminated meat, but U.S. intelligence sources suspected the outbreak was linked to secret weapons work at a nearby army lab.

In 1992, Russia allowed a U.S. team to visit Sverdlovsk. The team's investigation turned up telltale evidence in the lungs of victims that many died from inhalation anthrax, undoubtedly caused by the accidental release of aerosolized anthrax spores from the military base. Given the hundreds of tons of anthrax the Sverdlovsk facility could produce, the release of just a small amount of spores was fortunate.

News of the immensity of the Soviets' biological weapons program began to reach the West in 1989, when biologist Vladimir Pasechnik defected to Britain. The stories he told—of genetically altered "superplague," antibiotic-resistant anthrax, and long-range missiles designed to spread disease—were later confirmed by other defectors who had worked in the Soviet program, including Ken Alibek and Sergei Popov.

The Soviet program was spread over dozens of facilities and involved tens of thousands of specialists. In the late 1980s and 1990s, many of these scientists became free agents, and while there is no evidence that any went on to work on nefarious projects, the potential remains.

|

|

|

The Cults

In 1984, followers of the Indian guru Bagwan Shree Rajneesh, living on a compound in rural Oregon, sprinkled salmonella on salad bars throughout their county. It was a trial run for a proposed later attack. The Rajneeshees' scheme was to sicken local citizens and thus prevent them from voting in an upcoming election.

The trial attack was successful; it triggered more than 750 cases of food poisoning, 45 of which required hospitalization. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention launched an investigation but concluded that the outbreak was natural. It took a year, and an independent police investigation, to discover the true source.

While this first bioterrorist act on American soil went almost unnoticed, a decade later the work of another cult sparked a flurry of media coverage and government response.

In 1995, the apocalyptic religious sect Aum Shinrikyo released sarin gas in a Tokyo subway, killing 12 commuters and injuring thousands. (Pictured at left are some of the victims.) The cult's maniacal leader, Shoko Asahara, believed that he could recruit new followers by sparking fear, chaos, and social unrest. The cult also enlisted Ph.D. scientists to launch biological attacks. Between 1993 and 1995, Aum Shinrikyo tried as many as 10 times to spray botulinum toxin and anthrax in downtown Tokyo.

Just why the attacks failed is unclear, but some experts suspect the cult did not sufficiently refine the particle size of its agents and that it was working with an avirulent strain of anthrax.

|

|

|

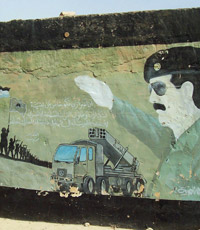

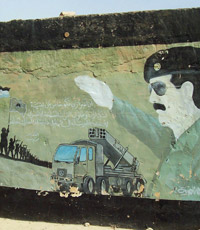

Iraq's Bioweapons

Under Saddam Hussein, Iraq launched a bioweapons program around 1985 but initially lacked the expertise to develop sophisticated arms. By the time of the Gulf War cease-fire in 1991, however, Iraq had weaponized anthrax, botulinum toxin, and aflatoxin, and had several other lethal agents in development. Inspectors from the U.N. Special Commission (UNSCOM) chased down evidence of the program, which Iraq repeatedly denied existed. The UNSCOM team found that Iraq's stockpile included Scud missiles, bombs, and artillery shells loaded to deliver disease.

Iraq was known to have unleashed chemical weapons on Kurdish civilians and Iranian soldiers in the 1980s, and while there was no evidence that the Iraqi state had ever used its biological arsenal, fear of this arsenal remained rampant.

In April 1991 the United Nations Security Council passed Resolution 687, which required Iraq to destroy any chemical, nuclear, and biological weapons. Nonetheless, suspicions that Iraq continued to harbor secret weapons of mass destruction persisted, and these fears led, infamously, to the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003.

It is now clear, however, that soon after the passage of Resolution 687, threatened by sanctions, Iraq destroyed the munitions and stockpiles of their bioweapons program as well as destroyed or hid all records of the program.

|

|

|

Anthrax Letters of 2001

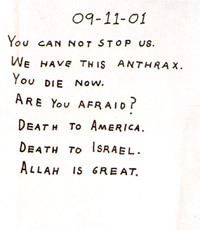

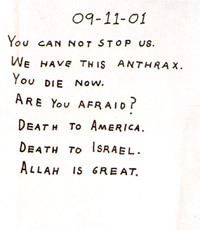

In the weeks following the terror of 9/11, reports that anthrax-laced letters had been sent to five media outlets and two U.S. Senators sent shockwaves through the nation. By the end of the year, 22 people had been infected with anthrax, five people had died of the inhaled form of the disease, and hundreds of millions more were struck by anxiety of the unknown. The message in the letters to Senators Tom Daschle and Patrick Leahy hinted at further attacks: "You can not stop us. We have this anthrax."

Yet in the months and years that followed, there were no subsequent attacks. And the FBI's resolution of the case in 2008 suggests that the anthrax letters were intended more to prompt fear about biological weapons than to kill. The FBI's forensic investigation, which relied heavily on comparative genomics, pinpointed the source of the anthrax—a flask in the lab of U.S. Army scientist Bruce Ivins, a senior biodefense researcher.

Whether or not Ivins himself was the culprit remains uncertain, but whoever sent the anthrax letters was likely an insider at the Army lab, someone with a vested interest in raising concern about biological weapons. It is telling that the letters were taped shut, perhaps a failed attempt to keep the spores from infecting postal workers, and that the messages within the letters clearly identified the anthrax and urged whoever opened the letters to "Take penacilin [sic] now." (The note about penicillin appeared in the first batch of letters sent, not in the letter to Senator Leahy shown at left.)

|

|

|