This portrait of Henry Gustav Molaison, or H.M., was taken shortly before he underwent the experimental surgery that would destroy his ability to form long-term memories.

The Molaison family, circa 1930. H.M. could recall major historic events of his childhood, such as the stock market crash in 1929, as well as the gist of activities like roller skating that he loved as a boy.

After his surgery, H.M. was largely homebound, and his life revolved around simple chores like grocery shopping, yet he retained a sense of humor and positive outlook.

Psychologist Brenda Milner tested H.M.'s ability to learn new skills, involving the formation of "motor memories," with this experiment in which he had to trace a star that he could see only in a mirror. Over time, his performance improved. Try it yourself in this activity from HHMI. More on HHMI and its partnership with NOVA

In 1974, H.M. and his mother moved to the home of a relative in Hartford, Connecticut who acted as their caregiver.

H.M. adored crossword puzzles, which he felt had a positive impact on his mental sharpness, and was a fan of the TV sitcom "All in the Family."

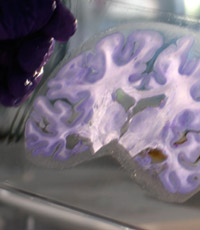

H.M. wanted neuroscientists to be able to continue studying his brain. After his death, Corkin oversaw MRI imaging work in Boston, after which neuroscientist Dr. Jacopo Annese transported his brain to a research facility at the University of California, San Diego.

Researchers at UCSD's Brain Observatory are currently preparing H.M.'s Brain for analysis. Eventually, images of these specimens will be available online. |

For five decades, neuroscientist Suzanne Corkin worked with Henry Gustav Molaison, a man known in the annals of science simply as H.M. She spent countless hours talking with him and testing him. She knew intimate details about his childhood, and he was one of the subjects of her Ph.D. thesis. Corkin was a familiar face to H.M., yet remarkably he could never remember who she was. In this interview Corkin, now a professor of behavioral neuroscience at MIT, describes her unique relationship with a "pure amnesic" who helped shed light on how memory works. A more in-depth account will be available in the book Corkin is writing about H.M., due to be published in 2010. An illustrious brainNOVA: It's been said that H.M. is one of the most studied patients in medical history. How so? Suzanne Corkin: H.M. was a research participant for 53 years, first at the Hartford Hospital with [William Beecher] Scoville and [Brenda] Milner, then at the Montreal Neurological Institute, and since 1964, at MIT and MGH [Massachusetts General Hospital]. Roughly 100 scientists have interviewed or tested H.M. He is the topic of many research papers and book chapters about memory. He's also highlighted in most introductory psychology books, in cognitive science and neuroscience textbooks, and also in advanced textbooks that graduate students and medical students use. So he's very well known within the academic community. He's also beginning to be known outside the academic community. And I think people will really enjoy hearing his story. Q: Is it fair to say that his brain, more than any other, has taught us what we know about our brains? Corkin: Well, he's certainly taught us a great deal about what we know about memory. Before H.M., the common view was that when you remember something, you're engaging your whole brain, or maybe your whole cerebral cortex—that all the neurons work together to evoke a memory. Once H.M. had this operation where Scoville removed this tiny area on the left and right sides of his brain in the middle part of the temporal lobes, and he immediately had a profound memory impairment, then we knew, aha! Memory, long-term memory—the ability to establish long-term memories—is localized to this tiny area in the brain. So that was the first big insight. Another insight was that you could have a profound memory loss and still be an intelligent person. H.M.'s IQ was 112 after his operation. Average is around 100. So he's above average intellectually. In addition, he didn't have perceptual deficits or language deficits. He didn't have psychiatric symptoms. He wasn't anxious. He wasn't depressed. He was what we call "pure," a pure amnesic. Q: As I understand it, H.M. underwent this operation as a last-resort attempt to cure his epilepsy. How severe was his condition? Corkin: His epilepsy was really incapacitating. He dropped out of one high school because the other boys teased him about his seizures. Then he went to a different high school and eventually graduated when he was 21 years old. He went to work at Ace Electric Motor Company, where he worked with two other men repairing motors. He also worked on an assembly line at Royal Typewriter. But he had to stop working because of the frequency of his seizures. It was just too dangerous for him to be in the workplace. So he was basically at home with his parents. His life was on hold. He was given very high doses of the anti-epileptic drugs that were available then, but to no avail. Scoville and his colleagues worked Henry up over a series of visits, tried to find a part of his brain where the seizures were starting, so that they could perhaps remove that part. Unfortunately, they didn't find this hot spot or trigger. So Scoville performed what he called a "frankly experimental operation" and took out the medial structures, the hippocampus and the surrounding cortex, on both sides, left and right. Q: Did it lessen the seizures? Corkin: It did, it did. After the operation, H.M. had very few seizures—some years not at all, other years he might have two. So in terms of the epilepsy, the operation accomplished its goal. But, of course, the tragedy was that he was unable to establish any new long-term memories after that. Living in the momentQ: In broad terms, how did this inability to form memories impact his life? Corkin: Well, he was completely dependent. He could never live independently. He lived at home with his mother and father after the operation. His daily routine included going to the market with her and carrying the groceries, mowing the lawn, raking the leaves, watching television, looking at newspapers and magazines, and that was pretty much it. He did not have much of a social life. One of his favorite pastimes, probably his most favorite pastime, was doing crossword puzzles. He would spend large amounts of the day with his crossword puzzle book. He believed that they were helping him, because when he did the puzzles he was remembering words. He was retrieving words from his long-term memory, from his semantic store. He had the insight to appreciate that he was remembering, and he thought this was helpful to him. And it probably was, in some way. Q: What was it like talking with him? Corkin: H.M. was very soft-spoken, and he loved to converse. You could be having a conversation with him, and within 15 minutes he would tell you the same story three times, in the same tone of voice, same vocabulary, and have no idea that he had told you the story before. Q: If he had just eaten lunch, would he remember what he had eaten? Corkin: He really had no continuity from minute to minute, hour to hour, day to day. If you talked to him in the afternoon and said, "Have you had lunch?," he would say, "I don't know" or "I guess so," but he would not remember what he had had. And if you asked, "What was your last meal?," he wouldn't know what it was. Q: You worked with him for five decades. Did he grow to recognize you and know you? Corkin: For many, many years, he thought that he knew me from high school. I would go to see him and I'd say, "Hi, Henry, how are you?" And he'd say, "I'm fine." I'd sort of say, "Have we ever met before?" And he'd say, "Yes." And I'd say, "Where?" And he'd say, "In high school." He said that every single time. So I must have evoked some feeling of familiarity. There must be something about me that reminded him of someone he interacted with in high school, a friend of some sort. Interestingly, years ago, I would give him a list of names, of last names, all beginning with C, and he could pick out Corkin. Now, he didn't know whether Corkin was male or female, and he couldn't tell you anything about Corkin, but he had familiarity. He recognized Corkin. More recently, maybe five years ago now, I was talking to a nurse from the nursing home. She said, "I just went into Henry's room, and I said to him, 'I was talking to your friend Suzanne from Boston,' and he said 'Corkin.'" So he had an association between Suzanne and Corkin. But he really didn't know who I was. Q: Was it frightening for him to encounter people repeatedly yet not really know who they were? Corkin: You might think that if you couldn't remember anybody, and if somebody walked into your room, you could react in either of two ways. You might feel very threatened—"I don't know this person. I need to be on the defensive, because this person might harm me." Or you could just accept everyone as a friend. And Henry did the latter. He wasn't fearful. Retaining old memoriesQ: He couldn't create new memories, but were the old ones from his childhood still intact? Corkin: H.M. definitely had memories from his preoperative years. His general knowledge about the world, what we call semantic knowledge, was excellent. So he could tell you about the [1929] stock market crash, and he could tell you about World War II, and he could tell you of the charge on San Juan Hill, and many public events. He also had memories of his personal life with his parents and other relatives. He could tell you about roller skating, which he loved to do. He could tell you about target practice. He would tell you what kind of guns he had, where he went in the woods to do target practice. He could tell you about neighbors, classmates in school, what schools he went to. He took banjo lessons. He could tell us all these details of his youth. What he couldn't do was tell you what happened at a particular time and place. He could not tell you, "I remember on my 10th birthday I spilled hot chocolate all over my white pants, and my mother was furious at me." We tried and tried and tried to get these specific, detailed memories, episodic memories, from him—something that happened on a holiday, or birthday, or whatever. He could not give one single episodic memory, with one exception—on one of his birthdays, [he remembered] going in a small plane and flying around Hartford. This obviously had a huge emotional impact on him. He loved this. So he had the gist of roller skating and all of these activities in his childhood, but no episodes. This suggests that there are different memory systems that support autobiographical memory—a unique event at a specific time and place—and another memory system that supports this "gist" knowledge, which was preserved in Henry. Q: What does H.M.'s ability to retain at least some sorts of memories from his youth mean about the storage of these memories? Corkin: It means memories are not stored in the hippocampus and the surrounding cortex that was removed in H.M. We believe that they're stored in a very distributive fashion in the cortex, all over the cortex, which was intact in his brain. Explicit and implicit memoriesQ: Brenda Milner did a famous experiment in which H.M. learned to trace a five-pointed star reflected in a mirror. So this man who couldn't form long-term memories seemed to learn something. What were the implications? Corkin: That was a groundbreaking finding, really, because it showed that memory—what we call declarative or explicit memory, where you're consciously remembering something—was supported by this little area in the middle part of the temporal lobes that Scoville removed. But because Henry could do mirror tracing and a lot of other motor-skill learning tasks, the message was, there are other brain areas that are doing this work. This fostered a huge amount of research to discover what areas support motor-skill learning and other kinds of learning without awareness. It turns out that very different parts of the brain support different kinds of learning. Q: So are there essentially two broad categories of memory? Corkin: Yes. Declarative, explicit memory is conscious recollection of facts and events. Non-declarative, implicit memory is learning that you demonstrate through your performance—tracing a star or reading a word faster [than you did previously]. Q: Has our understanding of different types of memory come a long way since you first met H.M.? Corkin: Yes. One thing that's very clear is that there are different kinds of memory, with different addresses in the brain. So if I ask you what you had for dinner last night, you are accessing a particular memory system. If I ask you what the capital of France is, you are accessing a different memory system. If I take you outside and say, "Jump on the bicycle and let me see how well you can ride it," and you get on and you say, "Wow! I haven't been on a bike in 20 years, and I can still do it," that's a different memory system. This idea of memory systems in humans and in animals is very well established now. More surprisesQ: Could H.M. tell you about where he lived, the house in which he lived? Corkin: He knew the address of the house that he moved to after his operation—63 Crescent Drive [in East Hartford, Connecticut]. He had a mental representation of that house. The mental representation was so good that he could actually draw the floor plan of the house accurately when he was at MIT. So he was in another state and drawing an accurate floor plan. When he first did this, I showed it to a nurse who was taking care of him and his mother for many years, a distant relative, and she said, "Yes, that's absolutely right." But when I wanted to publish this in a journal, years later, I thought, "I better find out if it's accurate, for sure." So I got in touch with the person who lives [in H.M.'s former house] now. As luck would have it, his job is making floor plans, and he sent me back the floor plan by return e-mail, and yes, it was right on. Q: How did H.M. form this kind of memory? Corkin: I think this is a kind of learning that took place very slowly, hour after hour. This was a small house, on one floor. He was largely confined to his house, because he couldn't go out independently. So he had many learning trials, walking through this house and building up a representation, every day, week, month, year, for many, many years. Q: He was 27 when he had his operation. Did he have a sense of himself aging? Was he surprised each time he looked in a mirror? Corkin: You might think that every time he walked into the bathroom, he'd come out screaming and say, "What happened to me? What did you do to me? I'm not supposed to look like this!" That never happened. No, he was very blasé. We would question him from time to time. One time we said, "Well, how do you think you look?" And he said, "Well, I'm not a boy." That was evidence of his wonderful sense of humor. Again, this was this very slow learning, every day, every week, month, year, for years, each time updating his mental representation of his face. Q: In the many years of research, were there other surprises? Corkin: We had a number of wonderful surprises with H.M. One came in an experiment conducted by Elizabeth Kensinger and Gail O'Kane, who were graduate students in my lab. They were interested in whether H.M. had any memory of celebrities who became famous after his operation. Remember, he watched television a lot. He read newspapers and magazines. He was probably intrigued by these people. So they showed him two names—one was a famous name, and the other was a name pulled out of the telephone book. And they just said to him, "Which is the famous name?" They had a set of preoperative names and postoperative names. And on the preoperative names, he was just as good as controls. He knew who was famous, and he knew why they were famous. For the postoperative names, where you might not expect him to know any of these people, he could identify the famous name above chance. If you have two names, you're going to get half of them correct by chance. So he was significantly above chance. Then, the next thing they said, "Well, why was this person famous?" And for a very small number of people, he could tell you why they were famous. He could give you unique, identifying details about these people. So, for example, for John Glenn, he said, "He was the first rocketeer." And for Lee Harvey Oswald, he said, "He assassinated the president." And for Liza Minnelli, he said, "She is a singer and a dancer, too." This is so astonishing. This kind of information is enough to make the examiner fall right off her chair. I mean, he has no business knowing this. So this was a wonderful surprise, that he had appreciated these people enough so that they stuck in his memory. I think that there was an emotional component to this, because these were people that he liked, or who had been associated with a violent event, like the assassination of Kennedy. I think that this extra processing from the emotional component made it stick better in his memory. Another funny thing—this was great—was that he knew that Archie Bunker called his son-in-law Meathead. It's astonishing that he would remember that, but he did. He probably watched this TV show, "All in the Family," week after week. He probably thought this [nickname] was really funny, and it stuck. Q: You said H.M. had a good sense of humor. Corkin: He did. He had a great sense of humor, which would just pop out in everyday activities. One day, Harvey Sagar, who was a postdoc in my lab, was testing H.M. in the Clinical Research Center [at MIT]. They walked out of the room, and the door closed. Harvey said to H.M., "I wonder if I left my keys in the room." And Henry said, "Well, at least if you did, you'll know where they are." [laughs] Another time Jenni Ogden, another postdoc, went into Henry's bedroom at the Clinical Research Center. She said, "I want to see how well you can keep track of time. I'm going to go out, and when I come back, I'm going to ask you how much time has passed." So she left the room at 2:05, and she came back at 2:17. She said, "Okay Henry, how much time passed since I left the room?" And he said, "Twelve minutes. Gotcha!" Well, clever man that he was, there was a clock on the wall, and he noticed what time it was when she left. He probably rehearsed over and over the whole time she was gone—said it to himself, fixated on the five, got a visual image of the five. And when she came back, he just did the subtraction, and that was it. Gotcha! Losing a friendQ: How did you feel this past December when you heard that H.M. had died? Corkin: When I got the call that H.M. had died, it was not a total surprise, because he had been on a decline for the past couple of years. And, in fact, that morning I had received word that he was having trouble breathing, and they were giving him oxygen. They also thought he might have pneumonia, and his doctor had prescribed an antibiotic. When I got the call, I was very sad. But at the same time, I also knew that there was important work to be done. H.M. and his conservator, quite a few years ago now, signed a brain donation form. H.M. wanted his brain to be studied after he died. We had explained to him why this was important, and he was happy to cooperate in this very, very important final segment of his research career. So after he died, we brought the body up to MGH, and we scanned for nine hours, overnight, collecting high-resolution scans of gray matter and white matter. In the middle of that night, I wrote his obituary. That was the first time that I had the opportunity to confront my emotions about his death. And I was very sad, because I realized that I had lost a friend of many, many years. It was hard. Q: Do you think H.M. was aware that he was contributing to science? Corkin: Well, from time to time I would say, "Henry, you know you are really famous because of all the research that you're helping us with." He would sheepishly say, "Oh, really?" He'd look sort of proud of himself. But 20 seconds later, he would forget it. So I tried to tell him from time to time, and he always seemed gratified. He would say, "Well, whatever I can do to help other people." He was very altruistic.

|

"He wasn't anxious. He wasn't depressed. He was what we call 'pure,' a pure amnesic." "Probably his most favorite pastime was doing crossword puzzles. ... He believed that they were helping him." "We tried and tried and tried to get these specific, detailed memories, episodic memories, from him." "One thing that's very clear is that there are different kinds of memory, with different addresses in the brain." |

|||||||||

|

Interview conducted in February 2009 by Sarah Holt, producer of "How Memory Works," and edited by Susan K. Lewis, senior editor of NOVA Online |

|||||||||||

|

© | Created June 2009 |

|||||||||||