Listen to audio highlights from this interview.

In South Korea, where most severely disabled people withdraw into obscurity, Sang-Mook Lee pursued his passion as a scientist and unwittingly became a celebrity.

After his undergraduate work at Seoul National University, Lee got a Ph.D. from MIT and the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

Even before his accident, Lee was something of an iconoclast in his culture—traveling the world's oceans and pursuing "blue-sky" basic scientific research.

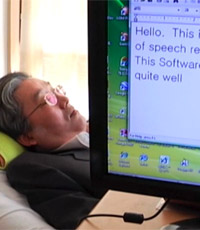

Roughly six months after the accident, aided by state-of-the-art assistive technologies, Lee returned to the lecture hall. He continues today with a full slate of teaching, mentoring graduate students, and research.

Being fluent in English has allowed Lee to use speech-recognition software. There is no equivalent software in the Korean language.

While the South Korean government has initiatives to make Seoul more handicapped-accessible, Lee must travel with his own ramp to make his way around the city. |

July 2, 2006 was a turning point in Sang-Mook Lee's life, one like few of us ever anticipate. On that bright summer day, Lee, a professor of geophysics at Seoul National University, was driving along a desert road in southern California, heading toward Death Valley on a geological field trip. Suddenly, his van flipped over, and he was crushed between the steering wheel and seat. He spent three days in a coma, and he emerged from the accident paralyzed from the neck down. What Lee calls his "near-death experience" changed forever his approach to science and to life. Producer Josh Seftel spoke to Lee about the experience, his advocacy work for the disabled, and more. Remarkably gratefulNOVA: How did your passion for science help you after the accident? Sang-Mook Lee: When I was injured, I didn't go through denial, depression. I just thought, "I must go back to work," you know? It was sort of like my love or interest in science, that I felt like there is a job that I have to do, that I have not finished that job. That kind of feeling, that kind of urgency, was what made me forget all the other obstacles and pain. So science played a very, very important part for me to come back after the injury. Q: Did the injury change your attitude toward your scientific work? Lee: Well, I appreciate science in a different way than I used to do, before my accident. Before, I just tried to survive in a very competitive world. But now I think about it more. I try to be more productive or more creative. Before my accident, I thought I had all the time in the world. Now I realize I have limited time, and I better use this time very, very efficiently to do something more meaningful. Q: I've heard you say that you were fortunate to have this accident. How so? Lee: There are many things that I realized and learned as a result of the accident. And I feel very fortunate, because most people just go through life without that kind of chance. But for me, I had an opportunity to reevaluate myself at the mid-point of my life. Q: What did you realize you wanted to change? Lee: First of all, you know, scientists are very—what you call—individualistic, very self-centered. Many good scientists are like that. That comes with the profession, I think. And I thought that even though I was self-centered and individualistic, if I make a contribution to science, everything will be paid off, you know? But I had what you call the near-death experience, and [during it] I knew that I was going to die, somehow. And one thing I really regretted is I did not have time to express my gratitude to other people—to the community, friends around me, my parents—how grateful I was for their help. I said to myself, "I'm not a bad person, but this sudden death has taken away an opportunity to say thank you to the other people. Well, but what can I do? I'm dying here." Then I later woke up [from the] coma. And then one day I realized again that, yeah, that's what I felt—sorry, when I was about to die. So if I have a chance to live again, this time I would not only be a person just receiving all these favors and achieving my goal, but also a person who can give back when there is an opportunity or chance. Another thing that changed is that—being a professor, at the moment when I knew I was dying, I graded my life. I thought, "What kind of grade can I give to this life? I've been relatively successful professionally. And I think I can give at most B+." Some might say B+ is a good grade. But I realized that I have devoted everything to work, and there is more than work in a human life. So I realized that if I have a chance to live again, I would aim for an A+ life, which means that not only do I try to do very well in work but in the other aspects of life. Well, I'm not sure whether I can get A+ in the end, but I should at least aim and try to achieve that. A rational approachQ: Where do you think your positive attitude toward your recovery came from? Lee: Well, I was very surprised that I reacted in the way that I did, even myself. Before the accident, I didn't consider myself as really, really, extra positive or optimistic, or as strong-willed. I just considered myself as another normal person. Q: Do you think your worldview as a scientist helped? Lee: Yes. People can become quite weak when they go into this kind of unexplainable difficulty. But for me, being a scientist really helped. I like to quote an interview that Richard Feynman had with a reporter. I was very moved by what he said. Richard Feynman was diagnosed with cancer, and a reporter asked him, "Now that you are about to die, what do you think about God and religious questions?" And Richard Feynman said, "Because I am a scientist, I am very accustomed to the fact that I don't know things. Everything has uncertainty." As a scientist, every day you look at nature and you realize that there are things that you don't know. Other people in my situation would have inclined to religion or to some other person's opinion. But I did not do that. I knew that whatever happened to me, nobody knows [why]. So scientific training made me accept the situation, I think, more reasonably. Q: How do you think your experience might have been different had you been injured in South Korea rather than in the U.S.? Lee: In Korea, if a person is injured like myself, he or she will spend at least three years in the hospital. But—well, this is ironic—but in the United States, the medical costs being so high, they would like to discharge people as quickly as possible. The medical cost in the United States is at least 10 or maybe 15 times higher than in Korea. In a way, I benefited from that harsh United States medical system and insurance policy. Q: So that actually helped you make a quicker recovery. Lee: Yes. And because I was injured in the United States, many of my relatives and friends who had weird ideas didn't have a chance to approach me while I was in the hospital. That may sound like a joke, but in Korea people's understanding of science and their trust is not as strong as in the Western world. In Korea, Oriental medicines and various non-traditional, alternative medicine cures still prevail. And it would have been very difficult for me to reject all those proposals. Q: Why do you think your return to your job became such a big story in Korea? That you've become such a celebrity? Lee: Well, the fact that a professor at Seoul National University, a very well-recognized position in Korea, got hurt, not only hurt, but is really crippled, and he's back on his job was—many people thought that was unbelievable. "How can he perform his job?" You know? "How can he recover so quickly and return back?" And for me, [the answer] was simple: using assistive technology, and I just wanted to get back as quickly as possible. But they thought it was something unbelievable. And they still do. Aiding the disabledQ: How did you start doing advocacy work for the disabled? Lee: Well, first of all, when I went back to Korea, I knew that I could function as a professor, [because] I saw these assistive technologies in the United States. And when I went back, one of the things that I did was check the web pages for various handicapped societies. I searched for people like myself, and I could not find many of them. There should be many severely handicapped, quadriplegic people like myself. But on the web, I saw there were very active Internet cafés and community get-togethers for handicapped people in Korea, but all of those people were able to use hands. People who could not use hands, more severely handicapped, just didn't participate in society, and they never had jobs. So the message I wanted to send was, "Hey, even [if] you cannot use hands at all, like myself, see how I teach students? See how I do my research? With the help of these computer devices." That was the message I wanted to send. I didn't expect that normal people would be impressed by that story. I just basically wanted to give information: "Hey, you see this device? It cost how many dollars, and with this, you can work many computers." I wanted to give technological information, not any moral message. But non-disabled people thought that was a bit cool. And then all the media started becoming interested in me. Q: Why do you want to encourage disabled people to train for jobs in science and technology? Lee: In Korea, people who are injured or handicapped tend to [become] lawyers and social workers. They seldom come to science and engineering, because they think nobody [like them] has really succeeded in that area. So I came with an idea, and I named that project ROPOS, which stands for Realizing Our Potential In Science. My idea is that if we educate and train disabled young people so that they can become programmers, engineers, or scientists—that would make them seek better-paying positions, and that would solve their economic troubles, their social-adjustment troubles. And if we provide them assistive tools so that they can work independently and live independently, without causing so much burden on their family, then that will solve the family problem as well. So assistive technology, providing those tools, and also giving them high-tech science and engineering education, will mitigate, lessen, the major challenges for the disabled. Q: How did you get government support for this work? Lee: Well, last year I got a call from a newspaper editor asking me if I would write a column about a blind man who recently passed the bar exam because the examiner provided special devices and tools for him to take the exam. I wrote this column, and somebody in the government read this column and was impressed. He contacted me and told me that his branch of the government wanted to do something about disabled people and assistive technology in Korea. And he asked me to design a national program on it. This was a big, big reward. Just one column! You know, we always write proposals, scientific proposals, to convince government to fund our research. But in this case, [they] came with the money to me. So I'm now in a position to do something really meaningful. A scientist at heartQ: You're also writing newspaper columns about science now, right? Lee: Yes. This year another newspaper—also a very, very popular newspaper—approached me, and this time they asked me to write about science. So I'm in a position to really tell to a larger audience what science means to me, and what the true nature, true character, of science is. Many people have misconceptions of it, especially in Korea. Q: How do you describe your scientific work? I've seen you referred to as a marine geophysicist, an oceanographer, and an Earth scientist. Lee: Well, that's a very good question, because that's the question I also get from Korean media. They ask me, "You say you are a marine geophysicist, and you are also oceanographer, and you're Earth scientist. What are you?" How does it all fit together? I tell them that Earth is 4.5 billion years old. But we know the recent 200 million years of Earth history very, very well, because all the records are preserved in the ocean. So what I do is go on a ship, study the past 200 million years of Earth's history, reconstruct it as precise as I can, and use that knowledge to understand how Earth has behaved in the past 4.5 billion years, and perhaps even use that information to project and speculate how other planets, other terrestrial planets, might have behaved. That's how I explain what I do, why I go to sea. Q: You plan to be involved, in a virtual way, in a number of upcoming oceanographic expeditions. How will you still be able to work "at sea," so to speak? Lee: I'm figuring that out. Every night, before I go to bed, I dream—I plan about this in my head. This is something that I'm going to focus on for the next five to 10 years, probably. And what's more [important] than being able to go on a boat is to keep your interests alive, you know? And I'm sure I can do that. I can send other people on the boat. Now, with the technology we have, we can communicate with a person on the boat as if he's across the room—a boardroom meeting—over the web cameras. So, well, I can enjoy science without getting seasick. This is a big perk for me, you know? [laughs] I'll send all the other people to sea, except myself. I'll sit here in the room, in front of my computer, and direct the whole operation from this end. Q: Seasickness aside, do you miss doing field research? Lee: Yes, I miss field research, because I want to be at the scene of the discovery, right at that moment. I want to see things myself. When you see things, your brain operates, and you get all this inspiration. That's the real fun part of science, you know? Being able to see things, being there, experiencing, doing the experiment, observations. But I guess I have to give that up and get other types of pleasure. |

"When I was injured, I didn't go through denial, depression. I just thought, 'I must go back to work.'" "I had an opportunity to reevaluate myself at the mid-point of my life." "Scientific training made me accept the situation, I think, more reasonably." |

|||||||||

|

Interviews conducted in December 2008 and April 2009 by Josh Seftel, producer of "Profile: Sang-Mook Lee," and edited by Susan K. Lewis, senior editor of NOVA Online |

|||||||||||

|

© | Created June 2009 |

|||||||||||