Harvard virologist Dr. Ann Kiessling says that "for a person to be able to use her own eggs for her own stem cells seems ethically appropriate."

Lauren Stanford, the teenager with Type 1 diabetes profiled on NOVA scienceNOW, is the type of person who experts like Ann Kiessling believe might someday benefit from parthenogenetic activation of their own eggs to produce stem cells.

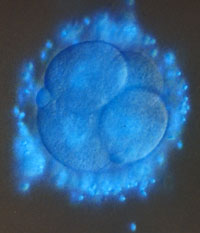

A parthenogenetically activated human egg 15 hours after activation. No such "parthenotes," as they're called, have ever been known to progress to full embryonic development.

To see how the nuclear transfer procedure works, see The Cloning Process.

Certain insects, including aphids like these, reproduce through parthenogenesis—that is, through development of the female egg without need of male sperm.

While human eggs sometimes activate on their own, they never go on to complete embryonic development. Here, a four-cell human egg. |

Media reports generally mention only two ways to produce human embryonic stem cells. Both techniques—the first using spare embryos from fertility clinics, the second involving cloning—are fraught with controversy. In this conversation with Ann Kiessling of Harvard Medical School, NOVA scienceNOW's Kyla Dunn learns about a third and possibly less contentious approach. It has the tongue-twisting name "parthenogenesis." No fertilization necessaryNOVA scienceNOW: Let's start with the basics. Just what is "parthenogenesis?" Kiessling: Parthenogenesis is the term that's applied to an egg that activates spontaneously on its own. This is relatively common in women. Eggs activate and often form cysts or benign tumors in the ovary. Those activated eggs begin to divide, and they look like embryos at the early stages. They form blastocysts with stem cells inside. NOVA scienceNOW: So you're looking at this as a way to produce stem cells for therapy? Give me an example of how it could work. Kiessling: Take a young woman with Type 1 diabetes. She could donate her eggs. The eggs then could be activated artificially in the laboratory without being fertilized. Those eggs would develop to the blastocyst stage, stem cells would be derived, and those stem cells—her own stem cells—could be used to treat her Type 1 diabetes. NOVA scienceNOW: Is this type of treatment just theoretical, or have there been animal studies? Kiessling: It's interesting. The only stem cells that are being used right now to treat Parkinson's disease in monkeys is a line of stem cells that were developed from an unfertilized monkey egg—an egg that went through parthenogenesis. The line of stem cells that was developed from that monkey egg has proven to be as valuable and as robust as stem cells from leftover fertilized human eggs [from fertility clinics]. NOVA scienceNOW: It's surprising that parthenogenesis hasn't gotten more attention in the media. Kiessling: It really hasn't been discussed. It's also surprising that parthenogenesis has not received much attention even from the research community. A private matterNOVA scienceNOW: Why do you think that is? Kiessling: One of the reasons the work has not gone forward is that, unfortunately, in the Dickey Amendment that was put in place by Congress in 1996, parthenogenesis was specifically lumped in with the rest of embryo research. So scientists cannot get federal funding to do work even on unfertilized human eggs. [Editor's note: The Dickey-Wicker Amendment, named for its authors, Republican Senators Jay Dickey and Roger Wicker, became law in early 1996 and has been renewed by Congress every year since. For more details on the ban, see The Politics of Stem Cells.] It would be very valuable if the Dickey Amendment could be modified as soon as possible to remove the term parthenogenesis, so that research funds could be applied for from the National Institutes of Health to study activated, unfertilized human eggs. Such eggs might be therapeutically valuable and will certainly lay the groundwork for the other types of stem cells that scientists are hoping to derive. NOVA scienceNOW: Would you argue that such work is really different from embryo research? Kiessling: There's never been a report of full embryonic development from an unfertilized human egg that was parthenogenetically activated. NOVA scienceNOW: If you took one of these embryos and put it in a uterus, what would happen? Kiessling: Well, we know that human eggs spontaneously activate on their own all the time. They undoubtedly occasionally end up in the uterus as activated eggs. But development has never been reported. So the potential for an activated human egg to develop into any kind of embryo is not there. Some animals do reproduce by parthenogenesis—some forms of insects do, for instance. But there's no parthenogenetic development in any mammal that's known. NOVA scienceNOW: Given that these embryos have no potential to develop into fully formed individuals, it seems like this is a way to sidestep a lot of ethical concerns. Kiessling: It avoids some of the ethical concerns of cloning or trying to use leftover embryos in fertility clinics. For a person to be able to use her own eggs for her own stem cells seems ethically appropriate. One piece of the puzzleNOVA scienceNOW: So is this the future for stem cell therapies? Kiessling: Human stem cells derived from parthenogenetically activated eggs are not going to solve the need for stem cell therapies. It's just one piece. Obviously it's only going to create tissue-matched stem cells for women who still are ovulating. You want to be able to create tissue-matched stem cells for everyone in need. But step one could be parthenogenesis, while regulations for the other forms of more controversial stem cell research are put in place. This would allow the field to go forward much more rapidly than it's going forward right now. Also, it's absolutely essential that we develop routine laboratory methods for activating a human egg or we'll never get nuclear transfer to work with any efficiency. [For a primer on nuclear transfer, see The Cloning Process.] NOVA scienceNOW: So post-menopausal women and men couldn't use this form of therapy? Kiessling: It's not going to benefit them unless they just happen to be a tissue match for that particular donor. So to satisfy the needs of men and older women who need stem cell therapies, you would either have to have a huge bank of parthenogenetically derived stem cells, or you're going to have to allow nuclear transfer work to go forward. NOVA scienceNOW: Do you think that success with parthenogensis is going to help convince people to move forward with nuclear transfer work? Kiessling: If a line of parthenote stem cells were developed and shown to be therapeutically successful for young women with Type 1 diabetes or spinal cord injury, perhaps it would get the attention of Congress. Men in Congress might realize that if they don't allow nuclear transfer work to go forward, they're going to be left out. NOVA scienceNOW: How close are you to actually developing a line of human stem cells using parthenogenesis? Kiessling: We think that we're very close—within the next few months. The system works very well in monkeys, and it's worked reasonably well in our experiments so far. We know that more than two-thirds of human eggs will activate in the laboratory. We think it's just going to be a matter of continuing the same lines of investigation. The constraint has been funding. NOVA scienceNOW: What about with nuclear transfer—we've been hearing for years that deriving stem cells through nuclear transfer is very promising. With so many people thinking about doing it for so long, why hasn't it gotten further by now? Kiessling: One major holdback to nuclear transfer technology has been that a large number of eggs are required to get a successful blastocyst. Making a donationNOVA scienceNOW: You've been involved in setting up a donor program. What do you think about the criticism that such stem cell research will lead to the exploitation of the great numbers of women that researchers would need to donate eggs? Kiessling: Some politicians have expressed concern that this is going to exploit women at a massive national level that cannot be allowed. That is definitely not the view of the donors who volunteered to participate in this research. These women are very glad to participate. Women can participate up to three times, and most of the donors elect to participate at least a second time. So they clearly don't feel exploited. NOVA scienceNOW: How did you go about establishing the program? Kiessling: When we first set up the egg-donor program four years ago, it was the first program in the country, probably in the world. And we wanted the guidelines for donor recruitment and donor participation to become the gold standard. We had to recruit and define an outside ethics advisory board. It met over the course of about a year and a half to two years to develop appropriate guidelines for women donating their eggs for stem cell research. [Editor's note: A Hasting's Center Report was published on the ethics advisory board and the process in 2002. The reference is: Hastings Center Report 32, No. 3 (2002): 27-33.] NOVA scienceNOW: One of the criticisms sometimes raised against cloning for stem cells is that many women have to donate eggs in what can be a risky procedure. How do you recruit egg donors? Kiessling: We put an ad in a local newspaper asking for women who are interested in voluntarily donating their eggs specifically for stem cell research. The donors apply, and then they go through several psychological tests. They must have their own child, which helps us understand a little bit how they're going to handle the hormones that are involved. They go through a lengthy physical examination. They're tested for a number of hormone irregularities, and then they are counseled about what they are doing, and they must actually have some interest in the research itself. The donors that answer our ads in the paper generally have a relative that has some disease that is possibly going to be treatable by stem cells, such as diabetes or Parkinson's disease or frequently heart failure. Working through controversyNOVA scienceNOW: You're on the Harvard faculty and affiliated with teaching hospitals in Boston. Why then did you set up the egg-donor program through a completely privately funded institution? Kiessling: The egg-donor program is carried on as a separate outside laboratory because of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) moratorium on funding this type of research. It's very difficult for NIH-funded institutions to establish the kinds of bookkeeping and accounting mechanisms that will avoid any possibility of conflict of interest, with the NIH funds. NOVA scienceNOW: Funding seems like a real stumbling block in much of this. Kiessling: Yes. And for nuclear transfer work it's been a major problem, and the main reason the work hasn't progressed more. The funding has not been available from the NIH because of the moratorium, and funding has been limited from the private sector, because there is a bill in place in Congress, and a bill before the Senate, that would actually outlaw nuclear transfer work. It isn't that it wouldn't be funded by the NIH; it would be that it would become illegal. Private investors are very reluctant to get very heavily involved in research that might become illegal. NOVA scienceNOW: With so much controversy, why do you stay in these waters?

Kiessling: We've surrounded our work with people of high ethical standards,

with a lot of experience in doing human-subjects research and with the goal of

going forward with this science in a completely ethical way. There are 100

million people in this country who might benefit from stem cell therapy. It

definitely seems like something that you should put your energies into.

|

“It’s absolutely essential that we develop routine laboratory methods for activating a human egg.” “There are 100 million people in this country who might benefit from stem cell therapy.” |

|||||||||

|

Interview conducted by Kyla Dunn, NOVA scienceNOW development producer, and edited by NOVA online editor Susan K. Lewis |

|||||||||||

|

© | Created April 2005 |

|||||||||||