It may work in the lab, but will RNAi radically change the practice of medicine?

|

|

In 2002, on the heels of the discovery that RNA interference existed in human

cells, the usually reserved journal Science proclaimed RNAi the

"breakthrough of the year." Here was a part of the body's natural immune system

that, it seemed, might be enlisted to fight almost every disease

imaginable—brain disorders like Huntington's and Alzheimer's, deadly

viral infections, cancer—every condition in which "silencing" rogue genes

might stop disease onset or progression.

But how close are we to seeing RNAi transform medicine, if it will at all?

There have been hundreds of successful experiments in petri dish cell cultures,

dozens in lab animals, and in late 2004, an RNAi therapy was tested in humans

for the first time. Yet experts in the field still see daunting obstacles ahead

for treating most diseases. The chief hurdles are how to deliver RNAi drugs to

the right targets, how to avoid veering "off-target" and shutting down good

genes or cellular processes, and how to ensure that the drugs stay active long

enough to help patients.

Despite these challenges, researchers are optimistic that many RNAi therapies

will enter clinical trials in the next five years and possibly get FDA approval

in the next decade. To glimpse some of the most promising areas of research,

click on the images above, or simply scroll down.—Susan K.

Lewis

|

| |

|

|

Macular degeneration is the leading cause of adult blindness in the developed

world.

|

|

It makes sense that the first RNAi therapy to reach patients in clinical trials

would aim at a debilitating eye disease called macular degeneration. Biotech

firms had set their sights on the disease for many reasons: Most critically,

RNAi drugs can be delivered directly to the diseased tissue—literally

injected into the eye. This direct delivery helps ensure that "naked" RNAi

drugs—short strands of RNA that aren't packaged and protected in

membranes and which quickly break down in the bloodstream—can reach their

target intact. Local delivery also makes it less likely that the drugs will

have unanticipated, harmful effects elsewhere in the body.

What's more, the disease is triggered by a well-known culprit—a protein

called VEGF that promotes blood vessel growth. In patients with macular

degeneration, too much of this protein leads to the sprouting of excess blood

vessels behind the retina. The blood vessels leak, clouding and often entirely

destroying vision. The new RNAi drugs shut down genes that produce VEGF and

allow it to make the leaky vessels.

The first clinical trial, involving about two dozen patients, launched in the

fall of 2004. While intended primarily to assess safety issues, this ongoing

trial shows promising results. Two months after being injected with the drug, a quarter of the patients had significantly clearer vision, and the other patients' vision had at least stabilized.

If subsequent trials prove they are effective, RNAi

drugs for this condition could hit the market by 2009.

|

| |

|

|

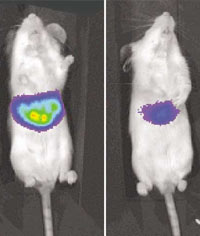

To test their RNAi treatment, Stanford researchers used mice infected with a

specially crafted, "glowing" version of a hepatitis C gene (left). The

treatment effectively turned off the glowing gene (right).

|

|

The RNA interference system that cells naturally possess likely evolved

millions of years ago, as organisms survived the onslaught of dangerous

invading viruses. So it makes sense that researchers are now trying to harness

the cell's RNAi machinery to fight a wide range of viruses. One of the most

noteworthy is hepatitis C, which infects roughly 200 million people worldwide

and causes an often fatal disease of the liver.

In 2002, geneticists Anton McCaffrey and Mark Kay at Stanford University

announced that their RNAi treatment had controlled the virus in laboratory

mice. It was the first time an RNAi approach had worked not just in lab cell

cultures but in living animals. In their initial experiments, the researchers

injected "naked" RNA strands into the tail veins of mice using a high-pressure,

rapid-transfusion method to ensure that the RNA strands were taken up in the

liver.

But the delivery method McCaffrey and Kay used, which doubled the mice's blood

volume within eight seconds, isn't feasible for humans. And even if it were,

the effects of naked RNA are likely to wear off in a matter of days. So these

researchers are exploring ways to use viral vectors—viruses stripped of

their harmful genes—to ferry RNA-making molecules into liver cells. It's

a technique that has been refined over a decade of gene therapy research and,

if successful, would provide long-term protection.

|

| |

|

|

A brain devastated by Huntington's disease, a genetic disorder for which there

is now no effective treatment or cure

|

|

To defeat hereditary diseases like Huntington's, doctors ideally want to shut

down the operation of a harmful gene over the lifetime of an individual. It's

another case where, rather than repeatedly administer "naked" RNAi drugs,

researchers hope to employ safe, stripped-down viruses to transport RNA-making

molecules to target cells. Once embedded in the cell's machinery, these

RNA-making molecules could continuously silence the troublesome gene.

In 2004, Beverly Davidson and colleagues at the University of Iowa used this

technique to treat mice with spinocerebellar ataxia, a neurological disorder

akin to Huntington's. It was a landmark—the first time that an actively

troublesome gene was put out of commission in such a way. Soon after, Davidson

treated mice with Huntington's, a disease that affects more than 30,000 people

in the U.S. alone.

But in the Huntington's experiments, there was a critical catch: in addition to

silencing the harmful gene, the treatment also shut down the healthy version of

the Huntington's gene. (Patients carry both.) While Davidson and other

researchers are optimistic that they can tweak the design of RNAi drugs to

overcome this obstacle, such "off-target" affects could hinder many RNAi

therapies.

|

| |

|

|

As with the best current HIV drug regimes, new RNAi therapies must attack the

virus on multiple fronts at once to counter the problem of drug resistance.

|

|

Almost as soon as RNA interference was discovered in human cells, scientists

began exploring how it could be recruited to battle HIV. By late 2002, Phillip

Sharp and colleagues at MIT announced they could interrupt various steps in the

HIV life cycle with RNAi molecules. But these and other experiments were

largely "proof-of-principle" studies, stopping the virus in cell cultures, not

human patients.

HIV mutates and evolves resistance so rapidly that any single target for an

RNAi therapy won't be sufficient. Molecular biologist John Rossi of City of

Hope Medical Center and colleagues at Colorado State University have

engineered an RNAi therapy aiming at multiple HIV genes. And to build up the

multipronged attack even more, Rossi combines this RNAi therapy with two other

RNA technologies (called ribozymes and RNA decoys) to block HIV's replication

and invasion of the immune system.

Rossi's group is tackling the critical issue of drug delivery in yet another

way. If it works, doctors might one day extract stem cells from a patient's

bone marrow, genetically alter these cells with the RNA therapy, then transfuse

them back into the patient, where they would develop into healthy immune-system

cells safeguarded against HIV. Rossi has established the therapy with mice and

rhesus monkeys, and hopes to move into clinical trials in 2006.

|

| |

|

|

A child's lungs, infected with RSV. The virus prompts as many as 125,000

pediatric hospitalizations in the U.S. each year.

|

|

For biotech firms aiming to bring RNAi therapies to market quickly, diseases of

the lung, like those of the eye, are prime candidates. It's relatively simple

to deliver RNAi drugs directly to the respiratory system—patients can

inhale them. One day, we may breathe in RNAi drugs for a host of different

viruses, including SARS and influenza. The first virus to be defeated in this

way, though, will likely be respiratory syncytial virus, or RSV.

RSV, while not commonly known by name, infects almost every child in the U.S.

by the age of two. Infection typically leads just to cold-like symptoms, but it

can have far graver consequences, including croup, pneumonia, and respiratory

failure. RSV also endangers the elderly and people with weak immune systems.

By early 2005, biochemist Sailen Barik at the University of South Alabama had

engineered RNAi molecules to shut down various RSV genes. Like the treatment

for macular degeneration, these molecules were short strands of "naked" RNA

that would rapidly break down in the bloodstream. When inhaled by mice, though,

the short RNA strands reached their targets intact and controlled the virus.

Clinical trials for RSV are slated to begin in the first half of 2006.

|

| |

|

|

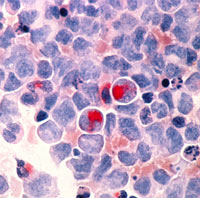

Because diseased cells of the blood system are relatively accessible,

leukemia may be among the first forms of cancer treated with RNAi drugs.

|

|

Cancer often involves mutant genes that promote uncontrolled cell growth. In

the last few years, researchers have silenced more than a dozen known

cancer-causing genes with RNAi. Yet, once again, most of this success has been

with cell cultures in the lab, and delivery poses the key hurdle in moving from

the lab to the bedside of patients. Researchers are just beginning, for

instance, to sort through how RNAi therapies might reach and penetrate

tumors.

Rather than take a leading role, some RNAi therapies may help defeat cancers by

supporting chemotherapy. Drug resistance is a major problem in chemotherapy,

thwarting between 20 and 50 percent of all current treatments. In many of these

failures, the guilty agent is a protein called P-glycoprotein. Like a misguided

housekeeper, this protein sweeps drugs out of diseased cells. In 2004, a team

of scientists at Imperial College London showed that RNAi can stop production

of the protein in multidrug-resistant leukemia cells, restoring their

sensitivity to existing drugs.

RNAi also provides a powerful new way for scientists to discover and learn more

about genes that trigger or inhibit cancer. Greg Hannon and his group at Cold

Spring Harbor Laboratory are part of an effort to decipher the function of

15,000 genes in a variety of human cancer cell lines. Such efforts might

pinpoint genes never before linked to cancer and generate novel ideas for

treatments.

|