A fortnight after Katrina, NOVA scienceNOW correspondent Peter Standring meets up with Walter Maestri (in black pants) in the deserted French Quarter.

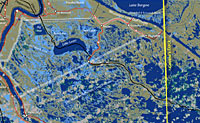

At a glance, a USGS map shows the possible extent of marshland loss (shown in light blue) southeast of New Orleans in the wake of Katrina.

"It gave the appearance of an ancient ruin just uncovered by archeologists," Doyle says of the End of the World Marina, here being taken in by fisheries expert Harry Blanchet. |

"One of the things we forgot is that Katrina is a terrorist." Walter Maestri, Emergency Manager for Jefferson Parish, said this to me as he surveyed a deserted French Quarter in New Orleans. It was Monday, September 12, two weeks after Katrina hit. The French Quarter was one of the few fortunate areas of the city to avoid the catastrophic floods that have turned New Orleans into a foul-smelling ghost town. Maestri has been a fixture on national television over the past few weeks. For years, he begged and badgered anyone who would listen about the flood risk from a hurricane. No one did listen. Now they can't get enough of his homespun wisdom. For Maestri, the events of August 29 are Louisiana's 9/11, a terrorist attack that, unconventionally, was known about ahead of time and ignored. This time it was not Islamic radicals but one of nature's terrorists, the Atlantic hurricane. Unlike the Middle East version, this terrorist did not belong to a sleeper cell. In the days prior to Katrina's attack, NASA, NOAA, and an alphabet soup of organizations and their experts had tracked the whereabouts of the coming storm. Katrina's every move, her every mood change, was charted, measured, analyzed. By August 28, they all sensed the worst was about to happen. New Orleans's last hope was her coastal defenses, the hundreds of thousands of square acres of marshland. Those marshlands had quelled and diverted storms from the city for 200 years. They were the ramparts holding back the furies of the elements. Over the past 70 years, however, 2,000 square miles of those marsh grasses had vanished. For an array of reasons—from changes to the Mississippi River that had starved the bayous of silt and sedimentation, to oil drilling in the Gulf—the marshes and wetlands were in poor shape. On August 29, the ramparts fell. In a real sense, those wetlands were a sacred battleground like Gettysburg, Verdun, Normandy—places where the course of history changed. A landscape in ruinThe following morning the Louisiana State Department of Wildlife and Fisheries invited me to tour the bayous. Except for a few National Guard troops, no one had gone down to see the place where what one might call the Battle of New Orleans had been all but completely lost. Our destination was Delacroix, a commercial fishing village. The town has one claim to fame—a mention in a Bob Dylan song—but for the most part it is off the beaten track to all but the most avid crabbers. Getting to Delacroix was a challenge. Traveling to and through New Orleans was difficult enough. Whatever roads were not underwater were manned by National Guard troops. For security reasons, and some reasons left unstated, those roadblocks moved, so at any given time on any given day no one could tell you how to get anywhere. I was lucky to be linked up with three of the Department's most knowledgeable specialists. Noel Kinler seemed to know the hideout of every alligator in the swamps. Harry Blanchet, the department manager, had a telepathic connection to the fish populations and to where illegal fishing nets were strung. And Heather Finley—well, she was a leading specialist in rare bayou birds. What those three didn't know about the wetlands probably wasn't worth knowing. It certainly helped that they knew the roads. Once past New Orleans and through the small towns of Reggio and Violet, the landscape changed. Road signs vanished. The open grasslands were brown and turning black, destroyed by the surging seawater. In the air hung the smell of decay, not the reek of sewers as in New Orleans but rather the pleasant smell of late fall. The roads narrowed the farther we drove into the bayous, finally becoming thin ribbons now heavily eroded, with dark pools of water and the occasional sickly yellow pond. The trees were stripped of leaves; many had been blown down; one brought us to a dead stop. On the other side of the tree the road had been destroyed, and a bright yellow torrent of water with a sulfurous smell was cascading into a lagoon. By the side of the road lay a dead horse, trapped by the storm waters just yards from its stall. Everywhere were signs of destruction. I knew I was entering the battlefield. Surveying the battlegroundA short detour brought us to Delacroix, where the road was lined with just the shells of buildings. There were clumps of dead marsh grasses everywhere, dangling from the remnants of buildings, the branches of trees, telephone poles. The End of The World Marina was festooned with so much marsh grass it gave the appearance of an ancient ruin just uncovered by archeologists. Making the view from the End of The World truly remarkable was the debris: boats lodged in trees, sticking out of the fetid marsh water, and jammed at strange angles into the skeletons of buildings. Along the road lay carcasses: an armadillo squashed on the pavement, dead crabs and snakes baking in the sun. Next to the End of The World was the rubble of a new home, destroyed except for, uncannily, a wet bar standing unscathed with a full complement of hard liquor. In the nearby bayou, next to what was once a boat landing, an overturned, partially submerged Chevy panel van lay where it had been hurled into the water. Across the road was the Roser home. I knew that because the mailbox was still standing in front of the ruin of what had once been their home. In their neighbor's yard, between the shattered cedar trees with plastic ducks hanging from their branches, stood a hackberry tree in full bloom. Trees that can withstand hurricane winds of 160 miles per hour? That came as a revelation. Out on the water, what remained of the marsh grass was broken up, some turning from brown to black. I asked Kinler if there was any chance it could recover. He thought for a while, then said slowly, "It depends on whether the silts and sediments can be replenished." I asked if that was likely. He told me it would be expensive, and the oil companies wouldn't like it because it would affect the waterways used to carry their cargoes, and the shrimp fishermen wouldn't like it because it would reduce their catch and would mean reconfiguring the Mississippi River.

What if they don't recover? I asked. "Well," he said, "then there's not much

point in rebuilding New Orleans." The thought struck me: then the Battle of New

Orleans would truly have been lost.

|

“Well,” he said, “then there’s not much point in rebuilding New Orleans.” |

|||||||||

Peter Doyle produced the Hurricane Katrina segment of NOVA scienceNOW's Episode 4 as well as segments in the previous three episodes. He would like to acknowledge his colleagues at Louisiana Public Broadcasting, without whom the four-day production of the Katrina segment would have been impossible. |

|||||||||||

|

© | Created October 2005 |

|||||||||||