Stem cell scientist George Daley of Harvard Medical School and Children's Hospital, Boston fears that the elusive search for controversy-free stem cells will derail promising research.

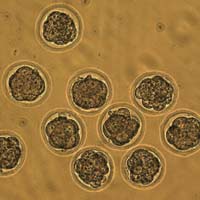

The method in dispute: removing the nucleus from an egg (in this case, a mouse egg) is the first step in cloning for stem cells. See the entire Cloning Process in this slide show.

MIT biologist Rudolf Jaenisch (right) and graduate student Alex Meissner have genetically engineered a mouse embryo incapable of forming a placenta and becoming a full-fledged fetus. Is this an ethical answer to the stem cell conundrum?

For many critics of stem cell research, even early-stage embryos that can never become fetuses may have a sacred moral status. Will it ever be possible to make embryonic stem cells without creating embryos first? |

Like most stem cell scientists, George Daley hopes passionately that there will one day be a technology to make patient-specific stem cells in a way that is ethically acceptable to even the most strident critics of today's research. But as he explains in this interview, conducted in November 2005, the science is just not there yet. Where we standNOVA scienceNOW: Where are we in the U.S. in terms of stem cell research? Are we making strides or creeping along? Daley: Well, the United States continues to have leading stem cell scientists. And despite some frustrations and limitations of federal funding, we continue to push ahead. But on an international basis, other scientists are doing work that is at the cutting edge, that we're virtually excluded from. And that's very disappointing and very frustrating. NOVA scienceNOW: Why is it frustrating? Daley: President Bush's policy, announced four years ago, allows federal funding for work on just a very small number of embryonic stem cell lines. There's an enormous swath of modern embryonic stem cell biology that we can't really pursue, or the challenges are great—we have to raise private money, buy independent equipment, have a separate laboratory. With the President's policy, we're essentially frozen in time at 2001, while the rest of the world has moved forward very, very aggressively. We have 22 cell lines available to us. There have been hundreds generated worldwide, many of which have advantages for medical research. NOVA scienceNOW: But there is legislation pending in the Senate, a bill that Senator Bill Frist has said he'd support, which would broaden the research, right? Daley: Yes. The bill would essentially remove the date of the Presidential policy and allow federally-funded researchers access to those hundreds of highly valuable stem cell lines. But it'll be politically challenging to get it through. NOVA scienceNOW: Because Bush strongly opposes it? Daley: Right. The bill, originally sponsored in the House by Mike Castle and Diane DeGette, passed in the House with a bipartisan majority. And there is clearly strong support in the Senate. But there's a lot of challenge politically. What's come up in some of the debates are the supposed "alternatives" for making stem cells. A number of legislators want to promote research on these alternatives. But some of their bills may actually be diversions and smoke screens. An ethical alternative?NOVA scienceNOW: Let's delve into some of these so-called alternatives. One, an experiment done by Robert Lanza of Advanced Cell Technology, involved taking just a single cell from an eight-cell mouse embryo. Was it a breakthrough? Daley: Well, the Lanza experiment allowed the extraction of a single cell from a very early embryo in a way that preserved the embryo; it could be put into the freezer for later use in reproduction. Then, from that single cell, embryonic stem cells were developed. It suggested that you could generate embryonic stem cells without destroying a human embryo. To some, that was an ethical step forward. There is by no means consensus, though, that this solves the problem. First of all, the method gives you only a generic stem cell. It doesn't allow you to make a stem cell that's matched to a particular disease or a particular patient. And that's really where scientists who are interested in studying disease or treating patients want to be.

NOVA scienceNOW: So this method could potentially be used to make stem cells from so-called "spare" embryos at in-vitro fertilization clinics without destroying the embryos. But IVF embryos can't provide you with all the stem cells you might need, right? Daley: Right. Lanza proposes extracting stem cells from IVF embryos that are being tested because a couple carries a genetic disorder. This may lead to stem cell lines for a narrow range of diseases. But most stem cells that come from the embryos left over after IVF are generic stem cells. They're the equivalent of isolating cells from any random individual on the street. NOVA scienceNOW: So they're limited. Daley: They're limited. Also, some people believe that extracting even a single cell is ethically problematic. We know that each cell is equivalent at the earliest stages of development. We can split the embryo in half and actually produce twins. Some scientists think that extracting a single cell is taking a twin. Also, there is some risk that extracting a cell will hurt the embryo and compromise its reproductive potential. NOVA scienceNOW: So does this experiment solve the ethical problems? Daley: It's fascinating science. But it doesn't get us what we really want—customized stem cells—and it doesn't solve the ethical conundrums. Customized stem cells without cloningNOVA scienceNOW: Let's turn to another method being touted as an alternative to cloning for stem cells. [For details of the method, see The Cloning Process.] It seems that this new method—called "altered nuclear transfer"—has the potential to make patient-specific stem cells in a way more people will find acceptable. Tell us about the experiment that Rudy Jaenisch of MIT did. Daley: The Jaenisch experiment is a technical tour de force. It's a beautiful bit of science—science that was aimed at addressing an ethical problem. It was an attempt to say, "Could we engineer into the donor cell—the skin cell from a patient—a defect so that it could not possibly generate a human life when its nucleus is transferred into an egg?" Now that sounds like it might address many of the ethical concerns up front. But you have to dig into the biology. What they did was engineer a defect in a gene that plays a role in the formation of the placenta. Without the gene, the embryo can't implant. It can't become a pregnancy. And yet the process produced, essentially, a normal early embryo. The principle [of altered nuclear transfer], I think, is an interesting one. The choice of gene in this experiment, though, won't quiet the most strident critics. For people who are concerned that we protect life from its earliest stages—even the single cell—this experiment does not satisfy their concerns. That's not to say that a different gene taken through the same process won't. Embryonic stem cells without an embryoNOVA scienceNOW: So in your opinion, these experiments—which have attracted a lot of media and political attention—don't really resolve the ethical problems. Can you envision something else that could satisfy the ethical concerns? Daley: What scientists really want to do is learn how to change the skin cell directly into an embryonic stem cell. The method that we use today, nuclear transfer*, reactivates in the skin cell all of the genes that are "on" in the early embryo. We essentially recreate an embryo from the skin cell. That is the problematic part. There are a number of genes, however, that one could imagine are important for embryonic stem cell function but that don't play a role in the early embryo. If you could make those genes turn on, you might directly turn the skin cell into an embryonic stem cell and not into an embryo. If we can get there, then I think we can satisfy even the very, very conservative and absolutist critics. NOVA scienceNOW: So the ideal is to take the egg out of the equation altogether? Just go from a regular skin cell to a stem cell? Daley: Right. We know today that we can take a skin cell and, using the environment of the egg, reawaken all of those embryonic genes. But it's just biochemistry. If we could understand what the egg is doing and apply it in the petri dish to the skin cell, that's the Holy Grail—that's what would give us the ability to manipulate the fate of skin cells for medical and therapeutic ends, and get away from some of these more contentious ethical issues. NOVA scienceNOW: Do we have any idea whether that's possible? Daley: It's theoretically possible. We know the egg can do it. NOVA scienceNOW: So if this is theoretically possible, should scientists abandon the more controversial method of using cloning to create stem cells? Daley: Not at all. I have patients, and I can see a way to apply this technology to study their disease and perhaps treat their disease. I want to be able to use that process today. I don't want to have to take the gamble and wait five, 10, 15 years to figure out how the egg's doing it. I feel that the goal of treating patients, the goal of attempting to relieve suffering—that more than justifies the ethical concerns. We don't take this approach lightly. There is some potential for human life in these cells. So I don't dismiss all of the considerations. But it's an ethical trade-off, one that I'm very comfortable making. Alternative paths leading nowhere, and worseNOVA scienceNOW: Are you concerned that research into alternative methods will derail work that you believe should be moving forward? Daley: When scientists proclaim that they can generate stem cells in a way that preserves the embryo, that's going to attract a lot of political attention. Legislators reading the science journals are embracing these alternative approaches. The problem is that, currently, these alternatives are really speculative. It's by no means clear that they'll work in human systems, by no means clear that they will solve the ethical problems. And these so-called alternatives could divert funding, divert attention, and continue this kind of obstructionist policy that prevents the science that we know works today from moving forward. That's my concern. NOVA scienceNOW: It's not that you're saying, "Don't fund research into alternative methods," but don't fund it instead of funding work on stem cell lines that already exist.

Daley: Exactly. The research into these other methods is valuable in and

of itself. It's important basic research. It should be funded, but it should

not be funded instead of the embryonic stem cell research that we know works

today. That's what's going to get us to medical insights and medical therapies

the quickest.

*Editor's note: Stem cell scientists generally refer to the process as "nuclear transfer" or "somatic cell nuclear transfer." The public knows it better as "cloning." |

“When scientists proclaim that they can generate stem cells in a way that preserves the embryo, that’s going to attract a lot of political attention.” “You might directly turn the skin cell into an embryonic stem cell and not into an embryo.” “These so-called alternatives could divert funding, divert attention, and continue this kind of obstructionist policy.” |

|||||||||

|

Interview conducted November 11, 2005 at Children's Hospital, Boston by Julia Cort, producer and correspondent for NOVA scienceNOW, and edited by Susan K. Lewis, editor of NOVA online |

|||||||||||

|

© | Created January 2006 |

|||||||||||