Oxyrhynchus lies about 100 miles southwest of Cairo, beneath the modern

village of el-Bahnasa.

|

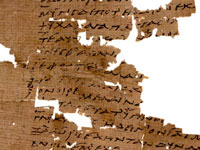

Who's ever heard of Oxyrhynchus? You're forgiven if you haven't, because this

ancient city still lies buried beneath Egypt's desert sands. Yet scholars

actually know heaps about this once-thriving cultural oasis, which during the

Greek and Roman occupations (332 B.C. - A.D. 641) became the third-largest city

in Egypt. How do they know so much? Because of the city's garbage dumps, specifically the thousands of

fragments of ancient writing on papyrus that were preserved there until British

archeologists dug them up in the late 19th century. Here, see a selection of papyrus

writings that have revealed a city and a time.—Rima Chaddha

|

|

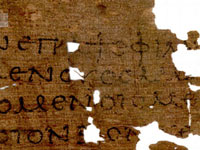

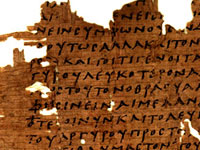

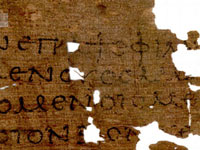

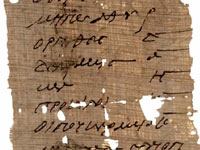

The Gospel of Thomas (3rd century)

"Know

what is in front of your face, and what is hidden from you will be disclosed to

you. For there is nothing hidden that will not be revealed."—Jesus

Christ, 5th saying

With a stroke of beginners' luck, one of the British team's earliest finds in

Oxyrhynchus was also one of its most important. The men stumbled upon

fragments of logia, or sayings of Jesus Christ, which until their discovery

had been lost for nearly two millennia. The publication and sale of these

lost sayings allowed the team to generate funding for additional excavations at Oxyrhynchus.

|

|

|

Adventures of Heracles (3rd century)

"[Heracles] built up the one entrance and came in upon the beast through the

other, and putting his arm round its neck held it tight till he had choked

it...."—Apollodorus, The Library, Book II

While it might look like part of an ancient comic strip, this colored drawing

comes from what was likely a schoolboy's reading assignment. The fragment and

its accompanying text illustrate the first of the 12 famous labors plaguing the

demigod Heracles: slaying the supposedly unconquerable Nemean Lion and bringing

back its skin.

|

|

|

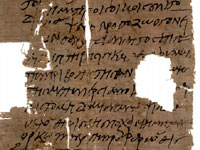

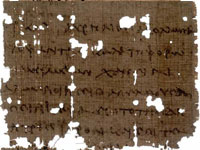

"The Tracking Satyrs" (c. 2nd century)

"What kind of a way to hunt is that, bent over and leaning down to the ground?

... You're lying there like a hedgehog fallen on the ground, or an ape sticking

his head forward and having a temper tantrum.... Where on earth did you learn

this, and how?"—Silenus to one of his satyr children, Ichneutae

This snippet of a once-lost comedic satyr play turned heads when scholars

translated it in the early 20th century. The author, it turns out, was famed

Greek tragedian Sophocles, who until a century ago had a reputation among

classicists for being too serious to venture into this genre of light-hearted

humor.

|

|

|

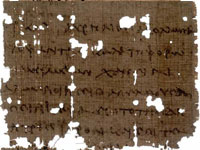

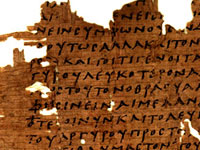

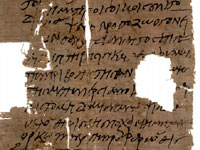

Lost poetry of Sappho (3rd century)

"My

heart's grown heavy, my knees will not support me /.... This state I oft

bemoan; but what's to do? / Not to grow old, being human, there's no

way."—Sappho, Book IV

Famous for her ability to capture human emotion, Greek lyric poetess Sappho

published nine volumes of poetry in her lifetime, all of which were lost until

excavators discovered a few fragments among the Oxyrhynchus papyri. Until the find, Sappho's influential works were known only through brief

quotations used by later authors.

|

|

|

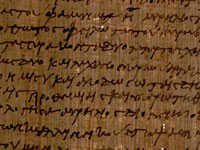

How to flatter a woman (2nd century)

"To an ugly woman, say that she is `fascinating,' and to a middle-aged one,

that she is a `wild pigeon.'"—Philaenis of Samos, The Art of

Love

When magical spells or advice from the local oracle failed to do the trick, the

upper-class citizens of Roman Oxyrhynchus could always improve their romantic

luck through handbooks like this one. Regarded as an authoritative guide to

passion in the ancient world—complete with advice on aphrodisiacs and

sexual positions—this is one of the few technical works of the time

believed to have been written by a woman.

|

|

|

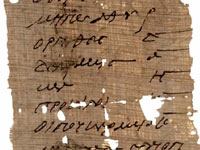

Letter to a priestess (after A.D. 217)

"You

will do well to go ... to the temple of Demeter to perform the usual sacrifices

on behalf of our lords and emperors and their victory and the rise of the Nile

and the increase of the crops and the healthy balance of the

climate."—Marcus Aurelius Apollonius, priest

This brief letter from a priest to a priestess provides a revealing look at the

multiculturalism of Greco-Roman Egypt. The temple and its deity Demeter, the

goddess of agriculture, are Greek; the "lords and emperors and their victory"

are Roman; and the sacrifice for the annual flooding of the Nile is a decidedly

Egyptian need.

|

|

|

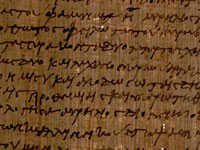

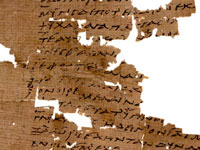

Acknowledgment of indebtedness (A.D. 223-224)

"If I fail to repay as is set down in this bond I will pay you interest at 50

percent, you retaining the right of execution on me and my possessions of any

and every sort."—Aurelius Papontos

Like most of the citizens of Oxyrhynchus, this man was illiterate and had to

hire a scribe to write this legal agreement. The employment of scribes had a major

influence upon the tone of all personal documents in Oxyrhynchus, even private

letters, which tended to be very formal and impersonal.

|

|

|

Against philosophers (2nd/3rd century)

"...[W]hat could be whiter than silver? Yet still Thrasyalces says that silver

is black. So, when even the whiteness of silver is on the doubtful side, what

wonder that men differ when they consult about peace and war, about alliance

and revenue and expenditure and things like that?"—Anonymous

Probably the work of a philistine or a rival philosopher, this fragment further

illustrates the assimilation of Greek life into ancient Oxyrhynchus as well as

its prevalence through the Roman-Egyptian period. The writer goes on to say

that madmen locked in a house would behave more peaceably than a group of

philosophers confined in their place.

|

|

|

Items for a sacrifice (c. 4th century)

"Hens, 4; piglet, 1; eggs, 8; cones, 8; jars of wine, 2; honey, milk, olive

oil, oil of sesame, a small measure of each; flower garlands, 8."—A list

of items for a sacrifice

Addressed to a beneficiarius (a Roman soldier on special assignment), this list

is typical of the items used in religious sacrifice. Written in the Egyptian

month of Hathyr, which corresponds largely to our modern November, these items

were probably requested in relation to an important winter festival.

|

|

|

Oath to care for the trees (A.D. 323)

"We agree, swearing the august divine oath by our lords the unconquered kings,

that we shall take every care of and do every service to and regularly irrigate

the persea tree ... for it is to propagate and to grow always."—A sworn

declaration from a group of men to Roman-Egyptian magistrate Dioscourides

Despite being employed under Roman administration in the fourth century,

Oxyrhynchus officials continued the ancient Greek practice of commissioning

contractors to plant and care for trees, generally in the city streets.

Religiously, the persea was considered the "tree of life."

|

|

|

A Latin will (2nd century)

"[M]y

sons and Claudia Techosis ... mother of my children, shall be my only heirs to

all my property in equal shares"—The last will and testament of C. Iulius

Diogenes

Even as the Romans came to power in Egypt in 30 B.C., most Oxyrhynchus

documents, whether official, religious, literary, or private, were still

written in Greek. But the use of Latin is not the only thing that makes this

will stand out. Few papyrus fragments of Roman wills exist today because

most wills were engraved on wax tablets; in fact, this document is likely a

copy of an official wax will.

|

|

|