On this page, you'll find regularly updated audio, video, and text reports from our producers and correspondents. We invite you to join the discussion about topics covered here on our board and to subscribe to our audio and video podcasts to download these reports to your computer or MP3 player.

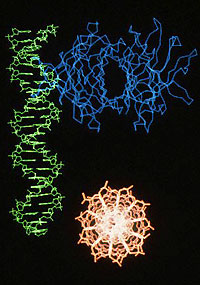

Are life's essential ingredients basic enough that scientists could whip up a living organism from scratch in a petri dish? |

7.21.2005 What Is Life?Robert Krulwich: So remind me what we were talking about. It's been a busy week. Jonah Lehrer: Well, I think we were about to discover the essence of life. Krulwich: Oh yeah, that. Lehrer: So, you'll remember there are labs in Maryland, Massachussetts, and New Mexico where scientists are trying two different routes to creating the first artificial life-form. Krulwich: Right, turning chemicals you buy in a store into a creature that's alive. Lehrer: Yes, the "Second Genesis," a headline-grabbing experiment. Krulwich: I'll say. Lehrer: It's really a way to ask a much deeper question: can we discover the simplest, bare-bones, essential recipe to create life? And then, and this is the big one— Krulwich: Isn't that two questions? Lehrer: Okay, sue me. There's two. But the second is the whopper: Is there MORE THAN ONE recipe for life? Krulwich:: You mean more than one way to cook it up? Lehrer: No, even deeper; is there more than one kind of life? Is there a way to create a living thing that's different from us? Krulwich: Different? Lehrer: Yes, different. Built differently, organized differently, from different ingredients, what the movie folks would call an alien. Right now all life on Earth that we're aware of is kind of like a big, sprawling family—built from the same ingredients, organized by the same rules. Krulwich: But maybe, just maybe, life CAN pop up in different forms if there are different kinds of life. The more life in the universe, the more creatures to meet. Lehrer: Or avoid, but that's what's fascinating about these artificial-life experiments. As I said, there are two approaches: Top Down and Bottom Up. With Top Down, scientists can take a teeny creature, take it apart, and try to put it back together again. With Bottom Up, you start with just the chemical ingredients, shake and shake and shake and see if life can assemble itself. Krulwich: Okay, so now we wait, right? And see if the Top Downers can produce life, or if the Bottom Uppers can produce life. Or maybe there's something in between. Do you have a hunch what's going to happen? Lehrer: Nope. Nobody knows. Krulwich: Well, I guess this is going to be a short conversation. Anything else you want to— Lehrer: No, no, no. Don't you see? Where the knowledge ends, the fun begins. Krulwich: Meaning what? Lehrer: Well, chew on this. Let's say that in a few years, when the Top Down and the Bottom Up folks have made lots of progress and each side has created a life-form, or an answer to the question of what is needed for life, suppose they come up with different answers? Krulwich: Different answers? As in, Top Down and Bottom Up don't agree? One approach says 2+2=3 and the other says 2+2=5? Lehrer: Exactly. For example— Krulwich: No. I'm done. Finito. If they don't get the same answer, then how do we know whom to believe? Did you ever think about that? Lehrer: Calm down. Of course I've thought about that. In fact, if Top Down and Bottom Up give us different answers, that would be an incredibly interesting discovery. Some say that would be the most interesting discovery. Krulwich: Wait a minute. When people give different answers to the same question, one of them has to be wrong, no? Lehrer: Not when it comes to the essence of life. Just think about it for a second. Let's say a Top Down team like Craig Venter's lab discovers the minimal subset of genes required to make the simplest possible life-form. Let's say, just for the sake of argument, that this itty-itty-itty-bitty thing needs 100 different genes. Krulwich: Okay, I follow you so far. Lehrer: Now, once scientists discover life's absolutely necessary genes—the genes that living things just can't do without—they will also have discovered what those genes encode for. And that, my skeptical friend, will be the Top-Down version of the essence of life. Krulwich: And? Lehrer: And what? Krulwich: What will they find? What will the essence of life be? Lehrer: Well, we'll just have to wait and see. But it will probably include some instructions for making a membrane, some instructions for creating energy, and some DNA that tells its DNA how to read itself. Everything will be crude but functional. Think Fiat, not Mercedes. Krulwich: Now I'm all confused. Lehrer: You? Confused? I'm shocked. Krulwich: I'm trying to be serious here, okay? How could the Bottom-Up approach come up with a different answer than the Top-Down approach? Doesn't all life need basic things like membranes and DNA? Lehrer: That's the assumption, and it's probably correct. But the real discovery will be in the details. What if the Bottom-Up approach—remember, that's the approach that tries to make life out of nothing but dust—comes up with a different kind of membrane, a different way to make energy, and even a different kind of DNA than the Top-Down approach? Krulwich: I see what you're getting at. So it's just possible— Lehrer: More like probable— Krulwich: That when we recreate the beginning of life, we'll see that life could have had any number of different beginnings. Lehrer: Exactly. We will realize that our particular version of life is just one of the many different forms that early life could have taken. For example, we might find that silicone-based life-forms (as opposed to carbon-based life-forms) are just as good at doing all the things that life does. Krulwich: Silicone? As in breast implants? Lehrer: Yup. Or that our membranes might have been made of something else. Or that oxygen could have been nitrogen. Or that— Krulwich: Enough already. What you're saying is we may discover that there is no one formula, no "everybody-has-to-have-it" recipe for life. No "essence." Lehrer: Maybe not. Krulwich: So there might be two recipes, or three. Life may be, well, kinda random. An accident? This isn't coming out well... Lehrer: Well, think of it this way: Living things are still pretty special. Think of all the gazillions of different ways atoms can come together. And yet, for whatever reason, only a precious few of those atomic jumbles contain the possibility of life. At the same time, however, we may discover that life has many different essences. Krulwich: So the lesson here is even if we humans could build a living thing we still may not know its essence? Still won't solve the mystery? Lehrer: Exactly. It may turn out, that after all this searching for our beginning all we really know is that we will never know why we are the peculiar way we are.

Stay tuned. Next week we'll discover the weird world of RNA and find out why

RNA, DNA's little cousin, might be the next big thing. |

|||||||||||

Robert Krulwich is host and executive editor of NOVA scienceNOW. Jonah Lehrer is a NOVA scienceNOW online contributing editor. He recently completed a Rhodes scholarship at Oxford University's Wolfson College. |

||||||||||||

|

© | Created July 2005 |

||||||||||||