On this page, you'll find regularly updated audio, video, and text reports from our producers and correspondents. We invite you to join the discussion about topics covered here on our board and to subscribe to our audio and video podcasts to download these reports to your computer or MP3 player.

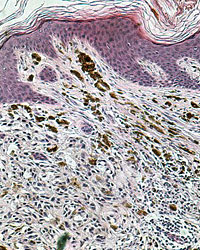

The microscopic brown flecks of early-stage skin cancer can go unnoticed, but nevertheless early-stage detection of melanoma has increased by almost 250 percent since 1986.

Handheld microscopes like this one, called MoleMax, can see skin cancers long before a doctor's naked eye can. |

8.25.2005 Is There a Skin Cancer Epidemic?Jonah Lehrer: Have you ever noticed how you can never notice something and then—all of a sudden—it's everywhere? Robert Krulwich: Of course. It's like yoga studios. Ten years ago I thought yoga was a Japanese yogurt. Now I see more yoga places than McDonalds. Lehrer: That's not quite what I mean. There really are more yoga studios now than there were 10 years ago. I'm talking about something that increases purely because you now pay attention to it. Krulwich: Oh, I get what you mean. Then it's like bird nests. I lived my whole life in the city and never noticed how birds build nests in the sliver of space between apartment buildings. But then one morning I was walking past—I guess it was a two-inch space, maybe less—that separated two tall luxury apartment houses, and I heard this chirping. So I stopped. I looked. And I couldn't believe it. There, in the teeny space that soared nine floors—nine human floors high—was a stack of finch nests. I don't mean a few nests. I mean, gosh, it must have been 800 nests, one on top of the other, higher and higher, as high as I could see. All jammed on top of one another in a two-inch space! I'd just discovered the Mother of All Finch Condos. Right there on Riverside Drive. Since then, I've seen bird nests nestled between buildings all over the city. They're everywhere! And while I'm sure they've always been there, I just never noticed them before. Lehrer: That's exactly what I'm talking about. Krulwich: But why? Are we talking about bird nests this week? Lehrer: Nope. Skin cancer is our topic. Krulwich: As usual, you befuddle me. What do finch nests and yoga have to do with skin cancer? Lehrer: Well, in a study published in last week's issue of the British Medical Journal, researchers announced that melanoma, the most deadly form of skin cancer, is not getting more common, even though it is being diagnosed at more than twice the rate it was in 1986. Krulwich: Wait a minute. Doctors say they are seeing MORE melanoma. What are you saying? That they aren't? That the rise in melanoma diagnoses is a mistake? Lehrer: Not quite. What the study did say was that the rise in skin cancer was due to a rise in skin cancer screening, and not due to a rise in the actual occurrence of cancer. Krulwich: Okay, I think I follow you. So it is like me looking at bird nests. Once I knew how to find them, I suddenly saw them everywhere. But there weren't actually more bird nests than before; I simply knew where to look. Lehrer: That's the idea. Krulwich: But how did these researchers prove that the rise in melanoma wasn't really a rise? After all, maybe there really is a higher incidence of cancer? I remember when everyone was talking about the hole in the ozone layer and how that would cause increased skin cancer rates. Or what about the increase in tanning salons? Half the people on the street look orange. Lehrer: To be fair, there are doctors who think those environmental factors might be causing a genuine melanoma epidemic. But this new study, led by Dr. H. Gilbert Welch of the Department of Veterans Affairs in White River Junction, Vermont and Dartmouth Medical School, analyzed the occurrence of melanoma at all stages of the disease, and not merely at the early stage, which is the stage usually diagnosed. Krulwich: And what did they find? Lehrer: According to their numbers, while early-stage melanoma has increased by almost 250 percent, there has not been an increase in the late stages of melanoma. Furthermore, the rate of people dying from melanoma has also stayed steady. Krulwich: So what we've got is an epidemic of early-stage melanoma only, which seems to be caused by the rise in skin cancer screening. Lehrer: That's what it looks like. Krulwich: But isn't that good news? Maybe all this screening has really lowered the death rates? Perhaps we are just catching skin cancer in its early throes, before it spreads? Lehrer: That's what some dermatologists argue. If you catch cancer early, the more likely you are to survive. And if you look closely at the statistics, it really does seem like melanoma is killing slightly fewer people. Krulwich: So what's the bad news? Lehrer: The numbers still don't add up. It seems that what is often diagnosed as "early-stage melanoma" would not necessarily become late-stage melanoma. Furthermore, if you are diagnosed with early-stage melanoma—even if your melanoma is not of the dangerous variety—your health insurance premiums soar. Also, removing pre-cancerous moles and doing biopsies on skin spots costs billions of dollars every year, and some of that clearly isn't necessary. Krulwich: But what can doctors do? They can't ignore skin spots that look dangerous. Lehrer: Well, it seems that dermatologists need a much better definition of what dangerous means. For every 100 biopsies done by dermatologists— Krulwich: Is that when they take a sample of your skin cells? Lehrer: Yeah, and it doesn't feel very good. But as I was saying, for every 100 biopsies performed, only one tissue sample turns out to be cancerous. Krulwich: That seems rather inefficient. Isn't there some tool that can help? How about a magnifying glass? Lehrer: That's actually not a bad idea. Some dermatologists already use a hand-held microscope (one of the more popular brands is called the MoleMax) to see cellular structures that the naked eye can't see. This way, they can cut down on unnecessary biopsies and surgeries. Krulwich: Is this phenomenon—let's call it the "bird nest syndrome"—suspected in any other medical fields? Lehrer: Absolutely. Public health officials are now scrutinizing the statistics of lots of different medical illnesses to see if increased diagnoses really reflect an increase in occurrence. Krulwich: What other diseases do they suspect? Lehrer: Autism is an oft-cited one. Some doctors think that the recent spike in autism is in part related to an increased awareness of the disorder and a parallel increase in the diagnoses of doctors. And while no one thinks that the bird nest syndrome explains the full rise in autism occurrence, many officials think it plays an important role. Krulwich: So what should I do the next time I see a bird's nest?

Lehrer: Just remember that the birds have probably been there for a while. The

nest hasn't changed; you've just learned how to see it.

|

|||||||||||

Robert Krulwich is host and executive editor of NOVA scienceNOW. Jonah Lehrer is a NOVA scienceNOW online contributing editor. He recently completed a Rhodes scholarship at Oxford University's Wolfson College. |

||||||||||||

|

© | Created August 2005 |

||||||||||||