Space Storms

- Posted 07.16.08

- NOVA scienceNOW

(This video is no longer available for streaming.) The aurora borealis, or northern lights, is one of nature's most spectacular performances, a celestial ballet of light dancing across the night sky. But the same forces that power this dazzling display can overwhelm power grids, fry electrical systems in satellites, even expose astronauts to deadly amounts of radiation. What to do? An unusual space mission aims to find out.

Transcript

SPACE STORMS

PBS Airdate: July 14, 2009

NEIL DeGRASSE TYSON: Welcome back. A breaking story tonight: big storm brewing. We've got a meteorologist in the field.

Can you hear me?

(As Meteorologist): Yes. As you can see, I'm in the thick of it out here!

Excuse me, but where are you?

(As Meteorologist): I'm out in space, orbiting Earth. And believe it or not, there's some serious storms up here. And they can cause all kinds of problems down there, especially with communications systems.

...seem to be having technical difficulties.

In the meantime, check this out.

Anyone who has seen the aurora borealis, or northern lights, will tell you they're one of nature's most spectacular performances, a celestial ballet of light, dancing across the night sky.

But it turns out there's much more to this dazzling display than meets the eye, because the same thing that powers the dance of the northern lights can also wreak havoc, exposing astronauts to deadly amounts of radiation, frying electrical systems in satellites and overwhelming power grids, causing widespread blackouts.

Problem is no one has ever been able to agree on the exact choreography of events that gives rise to both this beauty and danger.

JOHN BONNELL (University of California, Berkeley): This has been one of the persistent and difficult questions to solve in space physics.

NEIL DeGRASSE TYSON: But now, an unusual space mission is aiming to solve this mystery once and for all, because figuring out what makes the northern lights dance may also hold the key to predicting these kinds of events and avoiding disaster.

The northern lights take place more than 60 miles above the Earth's surface. But they're not caused by weather on Earth. They're caused something much less familiar, called "space weather."

Now, some of you may be thinking, "Space weather? It can't possibly rain or snow in space. I mean, you don't see astronauts shoveling out the Space Station, do you?" Well, turns out space has its own special kind of weather, thanks to that big ball of glowing gas we call the Sun.

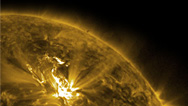

Every day, the sun spews out a million tons of electrically charged particles, which race away, at up to 300 miles per second, forming what's known as the solar wind.

Most of these particles are deflected by Earth's magnetic field, the protective shield that envelopes our planet. But some sneak through and eventually collide with air molecules.

When they hit oxygen, you get a red or a green glow; nitrogen, a blue glow, creating a steady ring of lights around the north and south magnetic poles.

But sometimes the whole process goes berserk. Huge amounts of energy from the solar wind build up in Earth's magnetic field and then are released in a sudden explosion called a substorm. And you can tell when that happens because the northern lights start to dance.

VASSILIS ANGELOPOULOS (University of California, Los Angeles): So the eruption of the aurora really corresponds to an eruption of a substorm, an energy release out in space.

NEIL DeGRASSE TYSON: But where do these violent space storms begin?

To find out, a team has launched a mission, called Themis, consisting of five identical satellites.

Wait a minute. Five satellites? Isn't that overkill?

Well, to see why they needed that many, think of a tsunami. A single buoy in the ocean can tell you if a tsunami has taken place. But if you want to figure out which way that wave is moving and how fast, you need multiple buoys, and it's the same with substorms. Except instead of buoys in the ocean, the Themis mission is using satellites.

The goal of the mission is to figure out where substorms start. And once every four days, the satellites enter the region of space where substorms occur to detect if they erupt near Earth or farther out in the magnetic field.

The Themis mission is operated at the University of California at Berkeley.

What am I looking at?

I see Earth in the middle.

MANFRED BESTER: That's right, and the five satellite orbits off to the right. This covers four days worth of orbit tracks.

NEIL DeGRASSE TYSON: And it's very clear when they all line up.

MANFRED BESTER: Exactly.

NEIL DeGRASSE TYSON: Themis is named for the Greek goddess of justice, that blindfolded lady holding the scales on courthouses. And just as the goddess weighed competing explanations to determine the truth, the Themis mission will try to determine which of two competing explanations for substorms is correct.

One theory locates the trigger for the violent release of energy relatively close to Earth; the other places that trigger much farther out in the magnetic field.

The evidence will be gathered by huge antennas on each satellite. And to see how they packed five of these into just one rocket, I paid a visit to one of the guys who designed them.

So where have you brought me? What is this place?

JOHN BONNELL: Well, so this is the mechanical engineering lab.

NEIL DeGRASSE TYSON: One antenna was designed like a high-tech jack-in-the-box. It was nicknamed "the death spike" for reasons that would soon become obvious.

JOHN BONNELL: And when I pull this string, it's going to release.

NEIL DeGRASSE TYSON: Can I give you a countdown?

JOHN BONNELL: Yes, go ahead.

NEIL DeGRASSE TYSON: Okay, ready? Five, four, three, two, one...

JOHN BONNELL: So, as you can see, about ten-foot up.

NEIL DeGRASSE TYSON: And with these antennas deployed, the team hopes the satellites will be in the right place at the right time, to catch a substorm in action.

JOHN BONNELL: It's like we've laid this trap, we've gone to the jungle, and we're waiting for the tiger.

NEIL DeGRASSE TYSON: And missions like Themis come not a moment too soon.

The sun works on an 11-year cycle, its activity level rising and falling with the number of magnetic disturbances, called sunspots, visible on the surface. Over the years, people have tried to link the sunspot cycle to everything from skirt lengths to stock prices. But the one thing we know it does relate to is space weather. And right now, we're entering a new solar cycle which will peak between 2011 and 2012.

Meanwhile, key data rests on Themis snaring a substorm, and not just any substorm: the five Themis satellites line up only once every four days in Earth's magnetic field, so the timing has to be just right.

It would be fun to be on one of these satellites, as you sort of come into alignment.

VASSILIS ANGELOPOULOS: And watch one of these auroras break up at the same time.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: No, I don't want to be there for that.

It takes two days for data from the outermost satellite to download to Earth. And in previous alignments, the team's already been lucky, snaring several substorms.

VASSILIS ANGELOPOULOS: This is when three substorms took place. One took place here, the next one about an hour later, and the next one about...yet another hour later.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: That's these peaks?

VASSILIS ANGELOPOULOS: These peaks.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: That's the bleeding edge of the frontier of science?

VASSILIS ANGELOPOULOS: That is exactly right.

NEIL DeGRASSE TYSON: They thought it might take years, but just three weeks after I left the Themis team, the satellites discovered the smoking gun: a huge substorm that unmistakably showed where these violent releases of energy are triggered.

So which theory was right? Was it a huge energy release near Earth, or a big explosion far away?

And the verdict is: far from Earth.

It's data that will improve space weather prediction and has solved, once and for all, the mystery of what makes the aurora dance.

On Screen Text: These are the sounds of the Northern Lights. Sometimes they sing; sometimes they crackle like footsteps in the snow. Some Inuit-speaking people believe them to represent the souls of their unborn children or the torches of long-departed ancestors. Some Yup'ik believe the aurora are their ancestors dancing in the sky, a reminder that they are still with them, watching over them.

Credits

SPACE STORMS

- Edited by

- Harlan Reiniger

- Written, Produced and Directed by

- Joseph McMaster

- Executive Producer

- Samuel Fine

- Executive Editor

- Neil deGrasse Tyson

- Senior Series Producer

- Vincent Liota

- Supervising Producers

- Stephen Sweigart

Joey David - Editorial Producer

- Julia Cort

- Development Producer

- Vinita Mehta

- Senior Editor

- David Chmura

- Online Editor

- Laura Raimondo

- Series Production Assistant

- Fran Laks

- Assistant Editors

-

Susan Perla

Tung-Jen (Sunny) Chiang - Compositors

- Brian Edgerton

Yunsik Noh - Music

- Rob Morsberger

- NOVA scienceNOW series animation

- Edgeworx

- Associate Producers

- Cully Gallagher

John Goebel

Daniel Sites

Anna Lee Strachan - Camera

-

John Chater

Austin de Besche

Brian Dowley

Joseph Friedman

Michael Phillips - Sound Recordists

- Ray Day

Lee Frank

Lisa Johnson

Charlie Macarone

Myron Partman - Sound Mix

- David Chmura

- Animation

- FIGG Bridge Engineers, Inc.

Anthony Kraus

David Margolies

Sputnik Animation

James LaPlante

Adam Tow - Production Assistants

- Mona Damluji

Nadira Ilana

Drew Grimes

Elizabeth Stachow - For Lone Wolf Documentary Group

- Executive Producer

- Kirk Wolfinger

- Production Manager

- Donna Huttemann

- For Twin Cities Public Television

- Executive Producer

- Richard Hudson

- Managing producer

- Lynn Winter

- Archival Material

- Federal Emergency Management Agency

Getty

Internet Moving Images Archive

ITN

Ville Karvinen

Knoxville Zoo

Jan Karel Lameer

The Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology

NASA

Penn State University Archives, Pennsylvania State University Libraries

Luc de Nil

WCCO-TV - Special Thanks

- Simon Baker

Aleksander Chernucho

Dennis Kavlakoglu

Libby Lewis Photography

The Methodist Neurological Institute

Museum of Science and Industry

New York Presbyterian Hospital, the University Hospital of Columbia and Cornell and Citigroup Biomedical Imaging Center

Ian Ryan

Phil Schneider

Sahar Salem

Veronica Smith

Francois Thibaut and The Language Workshop for Children

Waite House - Neil deGrasse Tyson

- is director of the Hayden Planetarium in the Rose Center for Earth and Space at the American Museum of Natural History.

- NOVA scienceNOW Consortium Stations

- Nebraska Educational Telecommunications, NET

Public Broadcasting for Northern California, KQED

Twin Cities Public Television, TPT

Wisconsin Public Television, WPT - NOVA Series Graphics

- yU + co.

- NOVA Theme Music

- Walter Werzowa

John Luker

Musikvergnuegen, Inc. - Additional NOVA Theme Music

- Ray Loring

Rob Morsberger - Post Production Online Editor

- Spencer Gentry

- Closed Captioning

- The Caption Center

- Publicity

- Carole McFall

Eileen Campion

Lindsay de la Rigaudiere

Victoria Louie

Kate Becker - Senior researcher

- Gaia Remerowski

- Production Coordinator

- Linda Callahan

- Paralegals

- Raphael Nemes

Sarah Erlandson - Talent Relations

- Scott Kardel, Esq.

Janice Flood - Legal Counsel

- Susan Rosen

- Post Production Assistant

- Darcy Forlenza

- Associate Producer, Post Production

- Patrick Carey

- Post Production Supervisor

- Regina O'Toole

- Post Production Editors

- Rebecca Nieto

Alex Kreuter - Post Production Manager

- Nathan Gunner

- Compliance Manager

- Linzy Emery

- Business Manager

- Joseph P. Tracy

- Producers, Special Projects

- Lisa Mirowitz

David Condon - Coordinating Producer

- Laurie Cahalane

- Senior Science Editor

- Evan Hadingham

- Senior Series Producer

- Melanie Wallace

- Managing Director

- Alan Ritsko

- Senior Executive Producer

- Paula S. Apsell

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. 0638931. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

NOVA scienceNOW is a trademark of the WGBH Educational Foundation

NOVA scienceNOW is produced for WGBH/Boston by NOVA

© 2008 WGBH Educational Foundation

All rights reserved

- Image credit: (Ofer Tchernichovski) Courtesy Ofer Tchernichovski

Participants

- Vassilis Angelopoulos

- The University of California, Los Angeles science.jpl.nasa.gov/people/Angelopoulos/

- Tom Bogdan

- NOAA Space Weather Prediction Center www.swpc.noaa.gov/AboutUs/Bogdan/index.html

- John Bonnell

- The University of California, Berkeley sprg.ssl.berkeley.edu/~jbonnell/

- Neil deGrasse Tyson

- Astrophysicist, American Museum of Natural History www.haydenplanetarium.org/tyson/profile/bio

- Michael Wiltberger

- National Center for Atmospheric Research www.ncar.ucar.edu/

Related Links

-

At the Edge of Space

Can scientists unravel the mysterious phenomena that lurk between Earth and space?

-

Space Storms: Expert Q&A

Vassilis Angelopoulos, team leader of NASA's THEMIS mission to study auroras, answers viewer questions.

-

Northern Lights

See a gallery of auroras above Earth and other planets, and hear the eerie sounds they make.

-

The Sun Lab

Research solar storms using images from NASA telescopes; share your work; and find out about careers in science.