Mystery of a Masterpiece

Art experts investigate whether a portrait sold for about $20,000 in 1998 is actually a lost Leonardo worth millions. Airing December 14, 2016 at 9 pm on PBS Aired December 14, 2016 on PBS

- Originally aired 01.25.12

Program Description

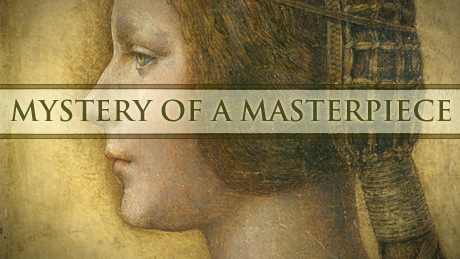

In October 2007, a striking portrait of a young woman in Renaissance dress made world news headlines. Originally sold nine years before for around $20,000, the portrait is now thought to be an undiscovered masterwork by Leonardo da Vinci worth more than $100 million. How did cutting-edge imaging analysis help tie the portrait to Leonardo? NOVA meets a new breed of experts who are approaching "cold case" art mysteries as if they were crime scenes, determined to discover "who committed the art." And it follows art sleuths as they deploy new techniques to combat the multibillion-dollar criminal market in stolen and fraudulent art.

Transcript

MYSTERY OF A MASTERPIECE

PBS Airdate: January 25, 2012

NARRATOR: He is, perhaps, the greatest artist of all time, a talent so unique, even his notebooks are worth tens of millions of dollars: Leonardo da Vinci, the genius who painted the Mona Lisa, whose rare finished works are among the treasures of the western world. So imagine getting your hands on a previously unknown portrait by Leonardo, a work like this, a profile of a mysterious young woman. If it really is a Leonardo, it could be worth a hundred million dollars. But first, you would have to prove it's authentic,…

PETER SILVERMAN (Art Collector): I don't have any doubt that it is by Leonardo da Vinci.

NARRATOR: …and counter the opinions of skeptics.

DAVID EKSERDJIAN (University of Leicester): This drawing does not seem to have any chance of being by Leonardo.

NARRATOR: Now, independent investigators will try to determine whether this portrait is real or fake, the work of some unknown artist of the past or a true Leonardo. They'll search for clues, probing deep beneath the layers of pigment, recreating the composition with original materials, and even digging into the mysteries surrounding the young woman and the creation of her portrait.

Surprising new finds: an unexpected fingerprint; a scar, left by a knife,…

MARTIN KEMP (Oxford University): The knife, which has been cutting down this edge, suddenly it slipped.

NARRATOR: …may unlock the Mystery of a Masterpiece, right now on this NOVA/National Geographic special.

It was an image that appeared out of nowhere, but it now may be worth a hundred million dollars. The reason is simple: this portrait may be a work by one of the greatest masters of all, Leonardo da Vinci.

The story begins in New York, on January 30th, 1998. Christie's auction house holds its annual sale of work by Old Masters. One of the items is an unusual piece: a profile of a young woman, drawn in chalk, on stretched animal skin, known as vellum, and glued to an oak panel. It's more like a painting than a drawing.

Christie's lists it as a German work from the early 19th century. Art collector Peter Silverman has flown to New York, from Paris, to be in town for the sale. He makes his living finding bargains and turning them for a profit, and he thinks Christie's might have made an enormous mistake.

PETER SILVERMAN: I said to myself, "This is really good. I don't understand why it's cataloged as 19th century." The first reaction is, "Well, maybe this is a discovery."

What it was, I wasn't sure, but I was sure it was not 19th century, and I was sure that it was either a fake, completely, or Italian.

NARRATOR: If it is older and Italian, it will be worth many times more than Christie's price. Silverman leaves a bid, but he doesn't go high enough.

PETER SILVERMAN: So, I left a bid at the auction house of, I think, $16,… or $18,000.

AUCTIONEER: Twenty thousand dollars. Any more bids? Thank you, sir.

NARRATOR: The drawing sells for just under $22,000 dollars. Peter Silverman misses his chance.

PETER SILVERMAN: I never thought I would see her again. No, I didn't think so, because things disappear into collections or vaults and things like that.

NARRATOR: But nine years later, Peter Silverman does see the drawing again, in a gallery on East 73rd Street, owned by a prominent dealer named Kate Ganz. It's a second chance he's not about to let slip by.

PETER SILVERMAN: Boom! Things just exploded in my mind and my heart, and I said, "My God, I couldn't believe my luck." And I asked Kate, "What's the price?" She said, "$22,000."

I didn't hesitate. Price, this price, fine, take it and that's done.

It's wrapped up in an envelope, and you put it under your arm, and you walk away with it, just like in the department store. Ha! Like a Vuitton bag or a pack of oranges.

NARRATOR: Back in Paris, Silverman begins to show off his latest purchase. Some art experts who see it say the work is unusual and probably is genuine Renaissance. As they examine it closely, a radical idea begins to take hold: what if this portrait is not just a Renaissance work, but one by a great master like Leonardo da Vinci? Just breathing the name Leonardo is like lobbing a bombshell into the staid world of art.

Perhaps the most intriguing figure in all of art, Leonardo da Vinci lived from 1452 to 1519. His boundless curiosity about science, natural history and the arts personified the Renaissance, but very few of his paintings survive. In all the museums in the world, there are only about a dozen paintings accepted as being from the master's hand.

MARTIN KEMP: There are very few Leonardos around. What he did was always so extraordinary: the manual gifts, the composition, the visual subtlety. They just have extraordinary presence, and we're only just understanding fully what he did.

NARRATOR: And now, Peter Silverman is coming to believe that a rare and extremely valuable Leonardo has fallen into his lap. If he's right, he stands to pocket not just thousands, but millions of dollars. But first he's got to prove, beyond a doubt, that Leonardo himself drew the portrait.

When it comes to a work of art, what does proof mean? The portrait is not signed. There's no record of its existence anywhere. Proving it as Leonardo's work means making a case on three fronts: artistic, historical, scientific.

But Silverman faces a formidable challenge; the art critics are deeply divided. He contacts Martin Kemp, one of the world's most influential Leonardo scholars. Kemp agrees to look at the portrait for no fee.

MARTIN KEMP: We can do a journey around the image, and we can look for a variety of things, but obviously you are looking for signs that this is a work of extraordinary quality.

NARRATOR: His expert eye is immediately drawn to details, like the headband and the ribbon holding back her hair, visible in this super-high-resolution image;…

MARTIN KEMP: If you look, for instance, at the band that goes across at the right angle, and then at the back, it pulls this little dip in the hair. Leonardo always had that wonderful feeling for the stuffness of materials, for how they react under pressure.

NARRATOR: …the fine work around the eye.

MARTIN KEMP: This is enormously magnified. You can see these little tiny marks, which must almost be done with a one-hair brush or something like that. And that lower lid, just look at that, the two little lashes there.

NARRATOR: The more he looks, the more he believes this is a previously undiscovered Leonardo da Vinci. But others are much less impressed than Kemp.

DAVID EKSERDJIAN: This drawing does not seem to me to have any chance of being by Leonardo.

NARRATOR: David Ekserdjian is one of many scholars who fail to see da Vinci's genius at work in the piece.

DAVID EKSERDJIAN: It doesn't correspond to his artistic practice, and actually, I don't think, in point of quality, it compares at all favorably with anything made by him. My personal hunch is that this one, over time, will, as they say, sink without trace.

NARRATOR: Even Martin Kemp is far from 100 percent sure.

MARTIN KEMP: Having had this extraordinary sort of feeling that there's something very special about this, you keep resisting that, because you can get carried away, and then you start seeing what you want to see. So, all the time, you're sort of pulling down and saying, "Hold on a minute," you know. "Don't go there. Don't get there."

NARRATOR: With art historians divided, Silverman knows he needs to build a forensic case, so he turns to Giammarco Cappuzzo, an Italian art specialist living in Paris.

GIAMMARCO CAPPUZZO (Art Specialist): He told me that he had a painting by Leonardo. And I said to him, "Look, are you joking? Are you feeling well? I mean, is everything okay with you?"

NARRATOR: Cappuzzo knows the questions will begin at a very basic level.

GIAMMARCO CAPPUZZO: They will ask you, "Why do you think that it could be a Leonardo? Why do you think that it's not 19th century? Why do you think that it's not a fake or a copy?" And you have to prove to these people that it's not 19th century.

NARRATOR: So the first obvious question: how old is it? In particular, what is the age of the animal skin, the vellum, the portrait is drawn on?

GIAMMARCO CAPPUZZO: When I saw the painting, I said, "First thing is the vellum, because if the vellum is not of Renaissance period, I will forget it."

NARRATOR: Cappuzzo takes a sample from the portrait to have its age determined through a process known as carbon-14 dating.

All plants absorb carbon atoms from the atmosphere. Carbon comes in many forms, including a radioactive type called carbon-14. Animals take in carbon-14 by eating plants. After they die, the amount of carbon-14 in their bodies begins to decay at a predictable rate. By measuring how much carbon-14 is still present in the remains, scientists can estimate how long ago the animal died.

In Silverman's case, the drawing is on vellum, or animal skin, and this will give a good idea of how old the vellum is.When the results come back, they point not to the 19th century but to the Renaissance.

They estimate there is a more than 95 percent probability that the vellum dated from the years 1440 to 1650. Leonardo lived from 1452 to 1519. So the age of the vellum overlaps Leonardo's life. But does that prove, scientifically, that the drawing on the vellum is by Leonardo da Vinci? Not by a long shot.

Fakers routinely use old materials to fool both art experts and scientists into thinking something is genuine when it's not. Leo Stevenson knows all about such tricks.

He makes his living by painting in the style of the great masters. He's not a forger, but he knows all the secrets of their craft.

Stevenson's home looks like a museum. It's filled with art that seems to be from different eras and different artists, but Stevenson himself painted every one.

Now, he prepares to sacrifice a recent purchase, worth about a hundred dollars, to create a new fake in the style of Claude Monet.

LEO STEVENSON (Artist and Historian of Forgery): A really good forger has to have the right materials. If we are doing a late 19th century canvas, it has to be on a late 19th century canvas.

This is a rather bad continental picture of the 1890s, but what I want it for is mainly for the back. And this shows it has an authentic maker's stamp, authentic stretcher, authentic condition. So if somebody sees this…if you fool the eye, you'll fool the mind. And the idea is to repaint this canvas to represent something far more valuable than it is, and you've fooled somebody.

So, this has existed for 120 years. We are now going to remove it.

NARRATOR: Stevenson uses methylene chloride—that's paint stripper—to dissolve the original.

LEO STEVENSON: This doesn't feel right, as one artist, destroying, effectively, the work of another artist. It is sort of morally wrong. But if we're going to do this exercise correctly, this is what a forger would do.

So, now we have a canvas as Monet would have expected it to look. Now we have to do the difficult bit.

NARRATOR: Like any con man, a forger's success depends on finding eager victims.

LEO STEVENSON: A forger is a trickster. He is using a person's expectations. If somebody believes something to be real or they want it to be or they expect it to be, he's in there. He will try to fool that person.

NARRATOR: He spends about 40 hours painting his fake Monet.

LEO STEVENSON: This is yours for two or three million dollars, if you're daft enough.

There are lots of forgeries out there. There are some paintings that are attributed to artists they shouldn't be. There are some outright fakes that have been made from scratch, like this, out there with major brand names attached to them, like Monet, and they're not the real deal.

NARRATOR: Every year, collectors unknowingly spend millions of dollars on works of art that are counterfeit. F.B.I. agent Jim Wynne usually has these paintings locked away in a secure evidence room. All of them were acquired during Wynne's art fraud investigations.

JAMES P. (JIM) WYNNE (Special Agent, FBI): This is a painting by Gauguin, purportedly. It had been consigned by a dealer to Christie's.

NARRATOR: This fake Gauguin sold for over $400,000.

These two "Chagalls" are identical fakes.

JIM WYNNE: These sold for in excess of $500,000 dollars each. Turn them around. There are certain things on the back that are important to establish authenticity.

NARRATOR: Auction stamps, signatures, even stains; all fake.

JIM WYNNE: If the original was here, it would be exactly like that. It would have the stains; it would have the signature, the sizing, everything identical. And this is all done to deceive. It's all done to try and establish the authenticity of these fakes.

NARRATOR: In the case of the portrait of the girl, the first scientific test, carbon dating, proved the vellum it was drawn on was from the Renaissance. But is the drawing itself as old as the vellum, or is it a modern fake?

Giammarco Cappuzzo now takes the portrait and Peter Silverman across Paris for another test.

GIAMMARCO CAPPUZZO: The piece is not so big, so it was inside an envelope, and [click] it went inside.

PETER SILVERMAN: I said, "Giammarco, please be careful, drive carefully. You have here, perhaps, a potentially 100-million-dollar painting, so if you have an accident you will never be forgiven."

NARRATOR: If Silverman has any hope of seeing a value as high as 100 million dollars, he'll need a lot more proof.

So Cappuzzo heads for a lab on the Boulevard Saint Germain, run by a world class expert in art imaging. His name is Pascal Cotte, and he has invented a special camera, capable of taking photographs with resolutions as high as 240 million pixels—1600 pixels per squre millimeter. The camera can also probe beneath the surface of the artwork to reveal secrets about its composition.

The Louvre museum even invited Cotte to examine one of its most valuable treasures: Leonardo's Mona Lisa.

Cotte used special data from his study of the masterpiece to digitally strip away centuries of tarnish and calculate the intensity and mix of its original colors: a virtual cleansing and restoration, revealing the Mona Lisa as Leonardo would have painted her.

Now, Cotte applies those same techniques to the portrait of the girl. He starts with super-high-resolution photos that enable him to magnify an image hundreds of times, without losing quality. Details, like the texture of her hair, appear with the click of a mouse.

Cotte's camera has another feature. It uses a rainbow of filters to reveal parts of the portrait completely invisible to the naked eye.

PASCAL COTTE (Scientific Director, Lumiere Technology/Translation): What's interesting are the infrared filters. They have the ability to penetrate inside the coat of the paint. One of the most innovative things about this camera is that there are three infrared filters, giving us three levels of depth.

NARRATOR: Cotte's rotating filters divide the image into 13 layers. Each layer shows what can be seen under different wavelengths of light. Different wavelengths reveal different details.

The most useful images from Cotte's camera are those from the infrared end of the scale. Here, the pen and ink lines, covered over by the chalk, become visible.

In the portrait of the girl, infrared reveals changes made during the process of composition.

PASCAL COTTE (Translation): You can see here, on the chin, there are some alterations. The most important changes were made on the forehead. They become visible with the infrared image. We can see, clearly, he has actually changed the outline of the profile.

NARRATOR: Cotte compares the revisions evident under the surface of the portrait to those found in a sketch everyone agrees is by Leonardo: "Portrait of a woman in profile," from the British Royal Collection. On the sketch, Leonardo's alterations can be seen with the naked eye.

And Cotte finds that the changes made to the sketch are strikingly similar to changes to the portrait, visible only in infrared images.

PASCAL COTTE (Translation): Here, around the neck, we find a small revision. There are alterations on both chins, a change to both foreheads, and on both necks; the same alterations in the same places. So, the habits of drawing are consistent.

NARRATOR: For Cotte, these signs of similar alterations are more than just coincidence; they're an argument for both portraits being by the same hand.

But couldn't another Renaissance artist, heavily influenced by da Vinci's technique, have drawn the portrait? Scholar Cristina Geddo studies the artists employed by Leonardo in his workshop.

CHRISTINA GEDDO (Art Historian/Translation): These are artists strongly influenced by Leonardo, but, at the same time, they are easy to identify.

NARRATOR: This drawing is by Giovanni Boltraffio, one of Leonardo's protégés.

CHRISTINA GEDDO (Translation): The only artist who compares to Leonardo, in terms of quality, is Boltraffio. But his way of drawing is very different.

NARRATOR: Geddo has seen the mysterious portrait, and she notes a telling feature Martin Kemp and others had noticed too. The pen marks used to create shading around the face are sloping in an unusual direction, typical of something rare in the Renaissance, an artist using his left hand.

MARTIN KEMP: A right-hander will do it that direction; a left-hander will naturally do it in that direction.

NARRATOR: No artist is better known for being left handed than Leonardo da Vinci.

CHRISTINA GEDDO (Translation): All of Leonardo's disciples are right handed; none of them work with the left hand.

NARRATOR: Boltraffio's right-handed pen strokes differ clearly from the left-handed marks so obvious in the mysterious portrait. If the drawing is not by Leonardo himself, it is the work of someone trying very hard to fake or copy his particular left-handed style.

Pascal Cotte continues to search through the image, looking for more clues of Leonardo's technique, when, suddenly, he finds something completely different.

PASCAL COTTE: I discover, on the top of the portrait, I discover that.

NARRATOR: On the upper left hand corner of the portrait, a faint but very definite fingerprint. Could this be the final proof?

There are fingerprints all over Leonardo's work. Using his hands to spread paint was one way he achieved his signature style. The "Ginevra de' Benci," in Washington, is smothered in hand and fingerprints.

MARTIN KEMP: "Cecilia Gallerani" has got them, the unfinished early "St. Jerome" in the Vatican has them.

NARRATOR: Is it possible that the fingerprint could place Leonardo at the scene? An analysis will be performed at the Institute of Criminology and Criminal Law in Lausanne, Switzerland where they specialize in answering the question: "Who done it?"

Here, students flock to the classroom of Professor Christophe Champod, a master at fingerprint identification. Champod is brought in to analyze the print Pascal Cotte found on the vellum of the mysterious portrait, and he quickly decides to ask others for their opinions.

Champod posts the image, unidentified, on a Web site and invites students and colleagues to offer their analyses. Forty-six examiners use a color-coded software to identify the characteristics of the fingerprint as they interpret them. For a ridge, they draw lines. For other aspects, called minutia, they use a different symbol. If they are sure about a mark, they use a solid line; when they are less sure, they use a dotted line.

The verdict on the 500-year-old print is conclusive.

CHRISTOPHE CHAMPOD (Université de Lausanne): If you overlay all the annotation from all of these examiners together, that's the sort of pattern you obtain. They are all dotted. There is very limited information which has been declared as to be reliable on this image.

NARRATOR: The written comments are clear.

CHRISTOPHE CHAMPOD: The mark is declared to be of no value, cannot be used. I consider this mark as being of no value; I cannot use it.

He has a few ridges, which are a reality, but there is no selectivity associated with these two ridges, because we have ridges everywhere on our opulary lines. This is not a rare feature at all. This is a feature you will find on anyone's fingerprint. I would find an association with anyone. I would find an association with you, because the amount of information is so limited.

NARRATOR: The partial fingerprint proves to be a dead end, and in the art world, doubts continue. Many do not believe the portrait reflects Leonardo's mastery.

DAVID EKSERDJIAN: The extent to which this particular work of art has divided opinion, I think, is quite unusual. I don't believe this drawing is by Leonardo. I am absolutely not alone in that opinion.

NARRATOR: Martin Kemp, the Oxford art historian, knows his reputation is on the line. He'll have to build a more convincing case.

Kemp asks artist Sarah Simblet, professor at the Ruskin School of Fine Art in Oxford and a world renowned drawing instructor, to attempt a recreation, using techniques and materials similar to the original.

SARAH SIMBLET (Ruskin School of Drawing and Fine Art, Oxford University/Author and Artist): The choices that Leonardo would have had would have been between sheep, goat and calf. The calf comes out thicker, and it gives you a much smoother, creamier surface to work with.

NARRATOR: Kemp is hoping Simblet's efforts will help him understand the unusual choice of chalk on vellum used in the portrait: typical of Leonardo's restless experimenting with techniques or a tip-off that it's a fake?

SARAH SIMBLET: So, you can see here, the whole shape of the animal still. Up at this end, it's very much thicker, because there's more fat in the animal.

MARTIN KEMP: It's in the nature of scientific evidence that 90 percent of it can be right, and if 10 percent of it's wrong, the whole thing collapses. So, all the way along, you're thinking, "One thing can emerge which will collapse the whole thing." So you always have to be looking for that. And as soon as you don't look for it, then you can get carried away.

NARRATOR: As Simblet works her way through the process, staining the vellum, testing the ink, and tracing the lines of the portrait, she begins to appreciate what it took to create the drawing.

SARAH SIMBLET: It's clear to me that this has been made by an exceptional draftsperson, someone who can draw exquisitely. As an anatomy teacher myself, I can see that the person who made this drawing understood about the development of the skull, for example.

The nose is very small in relation to the ear, which indicates that the facial bones haven't finished growing. Also, the degree of curvature on the eye—the person who has drawn this eye understands that the eyeball is elevated in the socket and that you're actually only seeing the lower quarter of the curvature of the ball.

If it's not done by Leonardo, then it's done by another artist who shares his knowledge of anatomy.

NARRATOR: In order to learn human anatomy, Leonardo dissected corpses himself and drew the exposed sinew, muscle and bone in astonishing detail. His studies brought new scientific realism to his portraits of living people.

To color the drawing, Sarah Simblet makes her own chalk from a variety of minerals, rich in natural pigments. Her biggest technical challenge is to get the chalk to stick to the vellum without blowing off.

That raises an important point: there are no other works by Leonardo on vellum. That's a problem for those who believe the portrait is a Leonardo. An unknown work done with unusual materials makes the skeptics doubly suspicious.

To make the chalk stay on the vellum, Simblet will use two kinds of binder, one made from tree sap and another from egg whites.

SARAH SIMBLET: The whole point of the binder mixed into the pigment is actually to make the pigments stick to the surface of the vellum and not just blow straight off. And you can see, even as I'm using it, it's inconsistent. There are places where it will suddenly come out with a great splurge, and then other places where it's barely, barely making a mark.

Maybe the pink will work on top of the white.

Well, slightly, very slightly.

I mean, an alternative would be—if we can't get this to stick— would be to grind up a little of this pigment and actually put it down directly with my fingertips. There's no reason why Leonardo couldn't have actually applied the colored chalks with his fingertips.

Yes! That works. We'll crack this eventually.

It's been exciting to see how this very strong, very magical, very beautiful, piece of work has been made out of such complicated process, using materials that don't naturally go together at all.

NARRATOR: For some, the unusual and experimental mix of materials is one more point in favor of Leonardo.

CHRISTINA GEDDO (Translation): We know Leonardo was an amazing experimenter, so much so that he failed sensationally.

NARRATOR: Leonardo's experiments sometimes got him into trouble. When painting "The Last Supper," in a monastery in Milan, da Vinci went against centuries of custom by developing a special binder that allowed him to paint directly onto a dry wall, rather than on wet plaster. But his experiment failed. Within 20 years, visitors to the monastery were reporting that the images of Jesus and his disciples were already flaking away.

The chalk-on-vellum technique used in the mysterious portrait is just as daring.

CHRISTINA GEDDO (Translation): Who better than Leonardo could have imagined something like this? Who could have created an artwork using such an absolutely experimental technique?

SARAH SIMBLET: I personally can't think of a single other work of art, single other drawing I've ever come across, that possesses this particular combination of materials and techniques with this sort of result.

NARRATOR: Sarah Simblet's experiment confirms the masterful technique needed to produce the portrait, and skeptics have not come up with an alternative.

What other left-handed artists in the Renaissance who could have done it?

And Pascal Cotte's photographic detective work into other parts of the portrait, invisible to the naked eye, reveals remarkable similarities to known Leonardo works.

Still, Martin Kemp knows he needs more positive proof. He decides to take a different tack and shifts his efforts to try and identify the girl. Who was she? And why was her portrait done?

Kemp focuses on one feature that might pinpoint where the girl lived and when: her hair.

Elisabetta Gnignera studies hairdos of the Italian Renaissance. Gnignera recognizes the long, bound ponytail as a particular style called a "coazzone," and she can trace the coazzone to a specific time, place and even royal family.

ELISABETTA GNIGNERA (Costume Historian/Translation): In 1491, Beatrice d'Este brought the coazzone hairstyle, here, to the Sforza court, in Milan, and it became an absolute must.

NARRATOR: During the Renaissance, Milan was one of the most formidable city-states in Europe. For 20 years, it was ruled by a family called the Sforzas. Ludovico Sforza was the most powerful man in Milan. When his wife adopted the coazzone style, the ladies of the court followed fashion.

ELISABETTA GNIGNERA (Translation): We have written reports that the hairstyle is in the Sforza court from 1491 to 1497 or '99, at the latest.

NARRATOR: It so happens, Leonardo da Vinci was living in Milan at exactly that time. From 1482 to 1499, he served Ludovico Sforza, his greatest patron, as an artist and engineer. Many of his most famous portraits were of people linked to Ludovico, including a court musician and a mistress.

Was the woman in the mysterious drawing also connected to Ludovico Sforza? Based on the hairstyle, Gnignera says yes.

ELISABETTA GNIGNERA (Translation): It seems to me the woman in the portrait was an important person, probably linked to the Sforza family.

NARRATOR: But who could that person be? Kemp generates a list of possible suspects.

MARTIN KEMP: You end up with relatively few candidates. Beatrice, Ludovico's wife, would be a candidate. She has a very distinctive jaw line, which is quite different from the jaw line in this portrait. There's Bianca Maria, she is Ludovico's niece, and she has a very characteristic face, um, and not a very appealing one.

Then, looking around the Sforza court histories, there was somebody who'd virtually been ignored. And that was Bianca, his illegitimate daughter.

NARRATOR: Histories reveal that Bianca, the illegitimate daughter of the powerful Ludovico Sforza, would have been about the right age for the girl in the portrait.

MARTIN KEMP: She was married when she was probably 13. She married Galeazzo Sanseverino, who is the commander of Ludovico's forces, an important man in Milan.

NARRATOR: Bianca Sforza died just four months after her wedding, possibly from a troubled pregnancy.

Now Martin Kemp's research is bringing Bianca Sforza back to life. She has the right hairstyle, she's a member of Milan's inner circle during Leonardo's time, and she is the daughter of da Vinci's patron.

In her honor, Kemp decides to give the portrait a name: "La Bella Principessa," the beautiful princess.

It's an exciting idea, but important questions remain. If the portrait was painted by Leonardo for his rich and powerful patron, why was there no record of this "principessa" anywhere? No copies by Leonardo's students? No listing in a royal inventory.

If Kemp can't trace the portrait's history, he's at another dead end.

But in his laboratory in Paris, imaging expert Pascal Cotte discovers some unusual marks that suggest where the portrait came from. Along the left side: signs of someone using a knife to cut the vellum.

MARTIN KEMP: We can pick up, at one point, where the knife, which has been cutting down this edge…and suddenly it slipped. Look. You can see there—slipped across—and they've probably slipped across twice and then gone back to cutting it the right way.

NARRATOR: And Cotte picks up another critical clue: one, two, three holes in the vellum.

Cotte passes his findings on to Martin Kemp, and Kemp begins to piece together a theory: what if the three holes came from the kind of stitching used in books? That might explain the knife cut, a scar left by someone cutting out a single page.

It's an idea that solves some problems for Kemp. It explains why the portrait is on vellum, why there are no accounts of the portrait hanging on a wall, and why it wasn't listed among Leonardo's works. As a page in a book, it would have been shut between the covers and fated to disappear onto a shelf.

But why would Bianca Sforza's portrait be placed in a book, and what book would it be?

MARTIN KEMP: My hypothesis, at this stage, is that it was in a volume of poetry dedicated to Bianca, the illegitimate daughter of Ludovico, probably on the occasion of her wedding, in 1496. And that it would have been, uh, maybe a frontispiece or something which was very striking.

NARRATOR: Kemp and Cotte are so convinced, they publish a book, including Cotte's photographs and technical analyses and Kemp's theories that it is a missing work by Leonardo, a portrait of Bianca Sforza, and that it must have been a page in a book celebrating her wedding.

But Kemp's writing fails to convince the skeptics.

DAVID EKSERDJIAN: There has been the suggestion that this drawing was part of some sort of commemorative volume. I confess that I am not aware of their being commemorative volumes of this kind which include drawings.

NARRATOR: But out of the blue, a stroke of luck. A series of emails from D.R. Edward Wright, a professor of art history from the University of South Florida, tells Kemp that there is something in the National Library in Poland he might want to take a look at. It's a break in the case that will send Kemp and Cotte to Warsaw and put doubters on the defensive.

DAVID EKSERDJIAN: If you are able to find a commemorative book which identified this woman as being the woman as she is meant to be and placed the execution of the book at the correct period, that's to say the period of her life in Milan, and let's say that the holes in the vellum of the other pages of the book absolutely corresponded, then I think you'd have to agree that the drawing belonged to the book.

If I were the possessor of a hat, and all of that happened, I'd be reasonably willing to get out the salt and pepper and eat it.

NARRATOR: Wright's emails to Kemp are pointing to just such a book: a history of the Sforza family called the Sforziada, 500 years old, printed on vellum. And, historians agree, created to commemorate the wedding of Bianca Sforza.

The book may have come to Warsaw after Bianca's death, carried here by a Sforza princess who married the king of Poland in 1518. Now, Martin Kemp and Pascal Cotte are at the Polish National Library, eager to see if this book might provide a missing piece of the Leonardo puzzle.

They want to find out: is there a page missing from the book? If there is, how will they be able to tell which page? The answer is in the way books are put together.

Books are assembled in sections: long sheets folded, gathered one inside another, and sewn together. If a single page is cut, the other half of the sheet would fly free, unless it were held in place somehow.

Kemp believes, if the portrait was in the book, it would have been placed as a frontispiece, near the full-page illumination. He examines the ends of the volume, trying to trace the individual sheets through the binding, but it's difficult to tell, with the naked eye, where one sheet of vellum ends and another begins. So Pascal Cotte will use a special camera, with a macro lens, to take a series of photographs, enabling him to trace individual sheets.

Each photo concentrates its focus on a specific point, and a special software stitches the photos together to create one giant close-up. The sections that make up the Sforziada come in three or four sheets. Mapping the first section reveals that it is made up of three.

When folded together, they should create six double-sided pages.

But one sheet of vellum, the first, marked here in yellow, never emerges from the other side of the binding. Unlike the others, it has no match. And, in a telling detail, it's been glued to the page next to it.

MARTIN KEMP: You can see very clearly at the edge there, how those two pages are stuck together. Yeah. And this bottom page then loops up, right? Let's track that through. Can we turn this over?

NARRATOR: Tracing the path of the remaining page, they find out where the missing page would have been: at the front of the book, right before the illumination, just as Martin Kemp had predicted.

MARTIN KEMP: And that's where she would have been.

PASCAL COTTE: Fantastic!

NARRATOR: But there is one more test, and it could bring the whole theory down: do the three holes on the side of the portrait match the stitching in the book?On Cotte's high-resolution facsimile of the portrait, the three holes are clearly visible.

MARTIN KEMP: You can see the stitch marks very clearly.

NARRATOR: There are actually five stitches in the book. But according to Polish archivists, the Sforziada was rebound centuries ago. And it's believed two stitches were added to the original three in order to strengthen the binding. At the same time, the pages were trimmed and the edges gilded.

Kemp and Cotte will compare the portrait to see if the three holes line up with the stitching in the book. If they don't, there is no way the portrait came from this volume. If they do, it will be strong evidence for Martin Kemp's case that the work is actually a lost portrait of Bianca Sforza by Leonardo da Vinci.

MARTIN KEMP: Now, on the portrait, we've got the marks down the edge, here, so what we're doing is we are matching the position of the stitch marks with the ones here. If you align the one at this point, here, if you align that, then that one and that one fall perfectly in line.

The three match these absolutely immaculately. Actually, it's fantastic.

PASCAL COTTE: Yes, it's fantastic.

NARRATOR: Against all odds, they seem to have found, in Poland, the very book Kemp imagined.

MARTIN KEMP: If you want to say…well, when I came here I was thinking…this is tolerably optimistic…that there was a 50 percent chance of this being right. Now, I'm prepared, if put into a corner, to say it's 80 percent!

NARRATOR: Kemp will continue his quest to fill in the gaps as he traces the strange and elusive journey of the portrait of a young woman from 15th-century Milan. But he has already uncovered intriguing evidence in the case for Leonardo. For Peter Silverman, the art collector who has the most to gain, it means he has some thinking to do.

For now, the Bella Principessa remains locked in a vault in secret Swiss location. Silverman continues to travel the world in search of new discoveries. When and where the portrait will next see the light of day depends on whether Kemp's new findings tip the scales in favor of Leonardo.

According to Silverman, an offer for the Principessa was recently made: $80 million. That offer, he says, was declined.

Broadcast Credits

MYSTERY OF A MASTERPIECE

- WRITTEN, PRODUCED AND DIRECTED BY

- David Murdock

- EDITED BY

- Emmanuel Mairesse

- ASSOCIATE PRODUCER

- Andrew Grimes

- CAMERA

- Douglas Hartington

Noel Smart - SOUND RECORDISTS

- Tony Burke

Mark Puffet - ADDITIONAL CAMERA

- Marcus Burnett

Nicholas Donnelly

David Murdock

Simon Normanton

Federico Padro

Roni Ulmann - ADDITIONAL SOUND

- Alessandro Codaglio

Patrick Duvoisin

Marek Zebrowski - FIXERS

- Allyson Luchak

Froggie Productions

Kasia Wozniak - NARRATED BY

- Jay O. Sanders

- ORIGINAL MUSIC

- Rob Kahn

Jim Morgan - ANIMATION

- Pixeldust Studios

- PRODUCTION MANAGER

- Nicole Hughes

- PRODUCTION COORDINATORS

- Katie Gross

Stefanie Kushner - POST PRODUCTION SUPERVISOR

- Susan Lach

- POST PRODUCTION COORDINATORS

- Bill Gabler

Laura Beth Ward - ASSISTANT EDITORS

- James Bates

Alison Kelley

Kate Kennedy

Carl Reeverts

Rin Westcott - ONLINE EDITOR

- Mark N. Boszko

- COLORIST

- Lauren Meschter

- AUDIO MIX AND SOUND EDITOR

- David Hurley

- TRANSLATION VOICEOVERS

- Maricruz Castillo Merlo

Emmanuel Mairesse - RESEARCH

- David Murdock

Teresa Neva Tate - PRODUCTION ASSISTANTS

- Marco Meazza

Ben Ring

Ben Schein

Jonny Sender

Maciek Wodyk - INTERN

- Kathryn Swanson

- ARCHIVAL MATERIAL

- Alinari/Art Resource, NY

Cameraphoto Arte, Venice/Art Resource, NY

Christ Church Picture Gallery, Oxford

Corbis Images

Erich Lessing/Art Resource, NY

HIP/Art Resource, NY

National Gallery of Art, Washington

National Gallery, London/Art Resource, NY

Reunion des Musees Nationaux/Art Resource, NY

Scala/ Art Resource, NY

Scala/Ministero per i Beni e Attivita culturali/Art Resource, NY - SPECIAL THANKS

- Arthur Brennan

Caroline Corrigan

Castello Sforzesco, Milano

Contrada Delle Braide

D.R. Edward Wright

Derek Miller & Jessy Kaner

Federica Babetto

James Margolin

Jeanne Marchig

Judd Flogdell

Jo Ann Caplin

National Gallery, London

National Library of Poland

Nicholas Turner - SENIOR EXECUTIVE PRODUCER,

NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC TELEVISION - John Bredar

- NOVA SERIES GRAPHICS

- yU + co.

- NOVA THEME MUSIC

- Walter Werzowa

John Luker

Musikvergnuegen, Inc. - ADDITIONAL NOVA THEME MUSIC

- Ray Loring

Rob Morsberger - POST PRODUCTION ONLINE EDITOR

- Spencer Gentry

- CLOSED CAPTIONING

- The Caption Center

- MARKETING AND PUBLICITY

- Karen Laverty

- PUBLICITY

- Eileen Campion

Victoria Louie - SENIOR RESEARCHER

- Kate Becker

- NOVA ADMINISTRATOR

- Kristen Sommerhalter

- PRODUCTION COORDINATOR

- Linda Callahan

- PARALEGAL

- Sarah Erlandson

- TALENT RELATIONS

- Scott Kardel, Esq.

Janice Flood - LEGAL COUNSEL

- Susan Rosen

- DIRECTOR OF EDUCATION

- Rachel Connolly

- DIGITAL PROJECTS MANAGER

- Kristine Allington

- DIRECTOR OF NEW MEDIA

- Lauren Aguirre

- ASSOCIATE PRODUCER

POST PRODUCTION - Patrick Carey

- POST PRODUCTION EDITOR

- Rebecca Nieto

- POST PRODUCTION MANAGER

- Nathan Gunner

- COMPLIANCE MANAGER

- Linzy Emery

- DEVELOPMENT PRODUCERS

- Pamela Rosenstein

David Condon - BUSINESS AND PRODUCTION MANAGER

- Jonathan Loewald

- SENIOR PRODUCER AND PROJECT DIRECTOR

- Lisa Mirowitz

- COORDINATING PRODUCER

- Laurie Cahalane

- SENIOR SCIENCE EDITOR

- Evan Hadingham

- SENIOR SERIES PRODUCER

- Melanie Wallace

- MANAGING DIRECTOR

- Alan Ritsko

- SENIOR EXECUTIVE PRODUCER

- Paula S. Apsell

- A Production of NOVA and National Geographic Television

- © 2011 NGHT, LLC and WGBH Educational Foundation

- All rights reserved

Image

- (La Bella Principessa)

- Courtesy Pascal Cotte/Lumiere-technology.com

Participants

- Giammarco Cappuzzo

- Art Specialist

- Christophe Champod

- Université de Lausanne

- Pascal Cotte

- Scientific Director, Lumiere Technology

- David Ekserdjian

- University of Leicester

- Cristina Geddo

- Art Historian

- Elisabetta Gnignera

- Costume Historian

- Martin Kemp

- Oxford University

- Peter Silverman

- Collector

- Sarah Simblet

- Author and Artist

- Leo Stevenson

- Artist & Historian of Forgery

- James P. Wynne

- Special Agent, FBI

Preview

Full Program | 52:52

Full program available for streaming through

Watch Online

Full program available

Soon

Related Links

-

Can Science Stop Crime?

Explore the genetics behind criminal minds, the latest in lie detection, a human corpse "farm," and more.

-

Art Authentication

See if clever computer algorithms can distinguish a master forgery from a masterpiece.

-

Art Authentication: Expert Q&A

Computer scientist Eric Postma of Maastricht University answers questions about the digital analysis of paintings.

-

Catching a Copy

See if you can tell a fake from a genuine van Gogh, and hear how one team of computer scientists did it.

-

Profile: Hany Farid

This self-proclaimed "accidental scientist" is a digital detective inventing new ways to tell if photos have been faked.

-

Hany Farid: Expert Q&A

Father of digital forensics and Dartmouth professor Hany Farid answers questions on photo fakeries and more.

-

Forensics on Trial

Virtual autopsies, 3-D fingerprints, and digital crime scenes are making crime-solving into a more precise science.

Additional funding for "Mystery of a Masterpiece" is provided by Millicent Bell, through the Millicent and Eugene Bell Foundation.

National corporate funding for NOVA is provided by Draper. Major funding for NOVA is provided by the David H. Koch Fund for Science, the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, and PBS viewers.