APPRAISER: Today, you brought us a Carnegie Medal awarded to your grandfather.

GUEST: Yes.

APPRAISER: How did he win this medal?

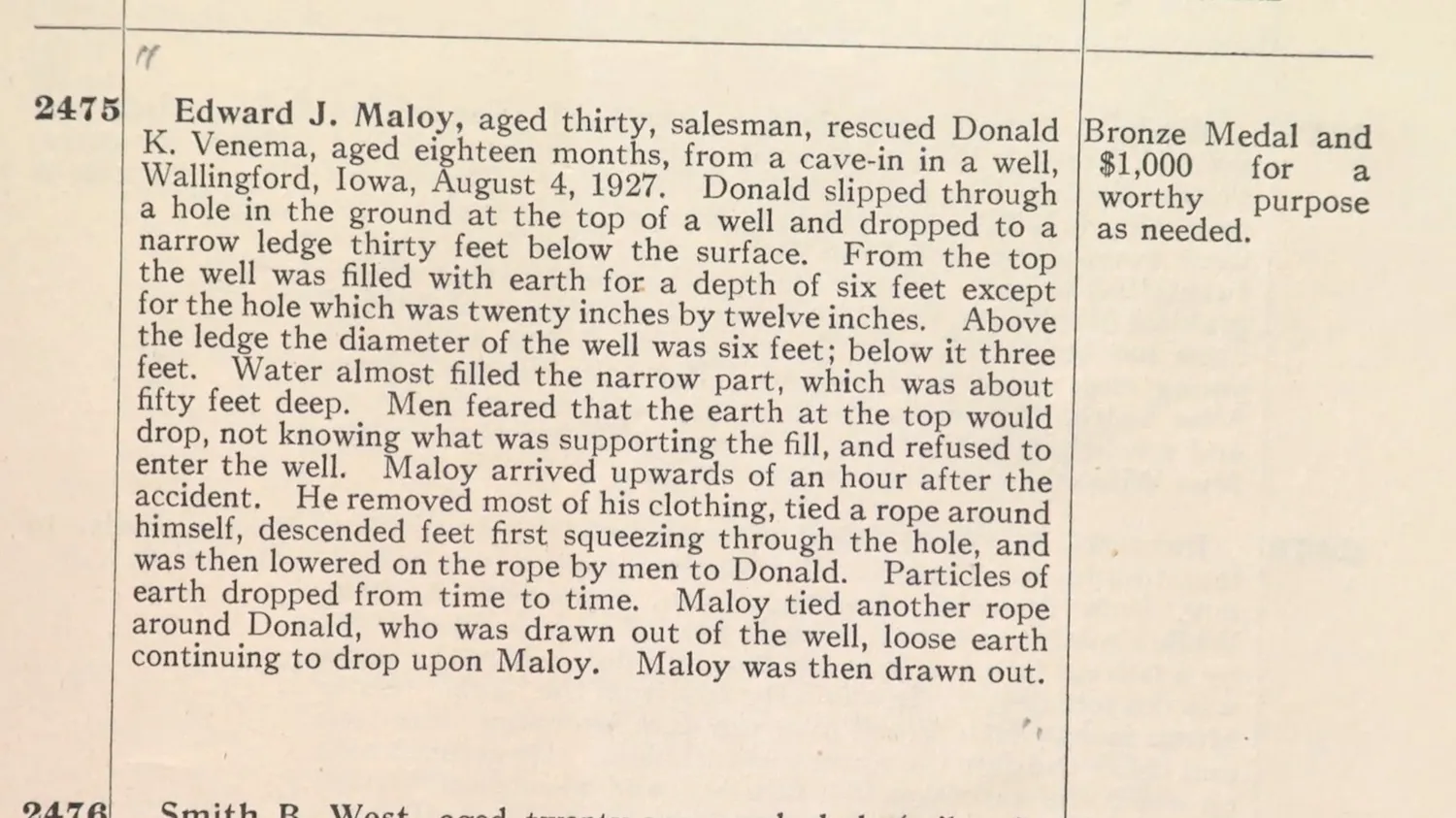

GUEST: In 1927, he was driving down the road in northern Iowa, and he happened to see a bunch of people standing in a field for some reason. And when he went over, he found that a baby had fallen down a well. And the baby had fallen down, I believe, ten or 15 feet to a ledge. And the other people there were either too big or not inclined to go down there, because the walls were collapsing as they were standing around it. My grandfather stood five feet three inches tall, so he was able to strip down to just about his underwear, I suppose, and they tied a rope around him, and sent him down the well. In the meantime, that baby had slipped down another... I believe it was another 30 feet down onto another ledge, right beside where the water was. So Grandpa had to go down almost 40, 50 feet to get to that baby. Tied a rope around him. They hauled the baby back up safely, squalling all the way, of course. Grandpa said the most scared he was was down at the bottom of that well, because it was caving in. Looking at that hole up there, he said it was just the size of a quarter. They finally pulled him out, and the baby was saved.

GUEST: So he essentially risked his life to save the baby's life.

APPRAISER: Yeah, most definitely.

GUEST: It was several years later when the baby's mother, Mrs. Venema, heard about the Carnegie Medal for Heroism, and asked his permission to put him in for this medal, which she did. And it took about a four-year process total for him to actually receive the Carnegie Medal.

APPRAISER: He rescued the 18-month-old in 1927, and he received the medal in 1931, this medal.

GUEST: Right, yes.

APPRAISER: Did he receive anything else?

GUEST: With this, kind of the height of the Depression, he received a cashier's check for $1,000. I remember him saying when he got the check, he took it to the bank to deposit it, and all the tellers passed it around and looked at it, because they'd never seen a check that big before.

APPRAISER: Andrew Carnegie is known by many faces. Of course he was a steel magnate. He came over from Scotland, made his fortune. He was also considered by some to be one of the major members of the Gilded Age. But nonetheless, very, very wealthy, largely thanks to his steel company, which he ended up selling to J.P. Morgan. But there was another side to Andrew Carnegie. He was a tremendous philanthropist. He gave a lot of money to institutions, largely for education. But he was always intrigued by the concept of heroism. There was a tremendous disaster in Harwick, Pennsylvania. You know, it's coal mining country, near Pittsburgh. In 1904, there was an explosion which killed 181 people, including two people, a mining engineer and a responder, a rescuer, who went to try to save these people, and they died. So, in response to this, for the two people who died, he established the Carnegie Hero Fund Commission. And their entire mission is to recognize and reward civilians who commit extraordinary acts of heroism.

GUEST: Oh.

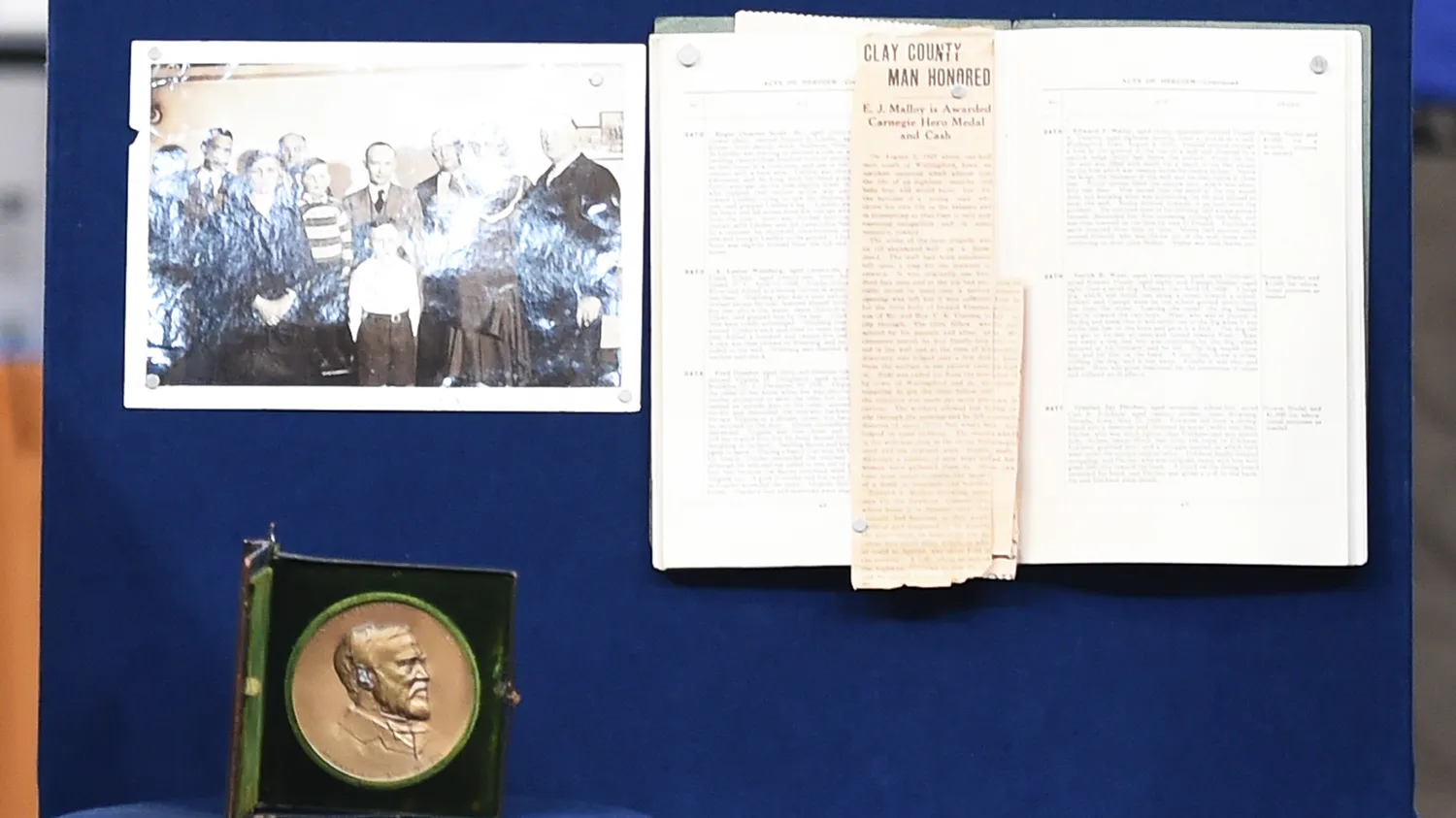

APPRAISER: So from 1904 to 2014, the Carnegie Foundation has awarded 9,600 medals to heroes, and they've also awarded over $35 million in grants. And you see this has been awarded to Edward Malloy. So, Carnegie's definition of a hero-- a civilian who knowingly risks his or her own life to an extraordinary degree while saving or attempting to save the life of another person. So this was a lifelong passion for him. It's said by many to be the only fund that he ever set up on his own out of his own heart. There's also a phrase that goes around this bronze medal, and it says, "Greater love hath no man than this-- that a man lay down his life for his friends." This is your grandfather, correct? This is Mr. Malloy.

GUEST: Yep.

APPRAISER: This is your father?

GUEST: Yep.

APPRAISER: This is...

GUEST: Donald Venema.

APPRAISER: And he was the 18-month-old who was rescued. J. and E. Caldwell made this medal, and they were considered by many to be equal to Tiffany in being able to produce high-level silver and bronze products. You can't find one for sale. As you might imagine, why would a hero want to sell, or why would the family of a hero want to sell the medal? But in thinking about what it might cost to reproduce a medal in bronze today, I would probably insure it for about $4,000.

GUEST: Oh, okay, all right.

APPRAISER: But really, at the end of the day, you cannot put a price on heroism.

GUEST: Yeah, I can't imagine the circumstances that I would sell that medal.