GUEST: I like to go to estate sales. I'm sure I picked this up at an estate sale, but I don't remember how long ago it was. And I just like to look at nice things, and quality things that most of which I can't afford. And I saw this, and I opened it up, and read the card on the inside, and it said that it was museum quality set, and I thought, "Oh, okay, I'm buying this." (chuckles)

APPRAISER: Do you recall how much you paid for them?

GUEST: It was less than $20 because I don't spend that much. I really didn't know that much about them, and as I started doing research, it said that the whole set should be kept together. And that these were made from the original plates, Goya plates.

APPRAISER: Yeah.

GUEST: And I thought, "Oh, that's pretty nice."

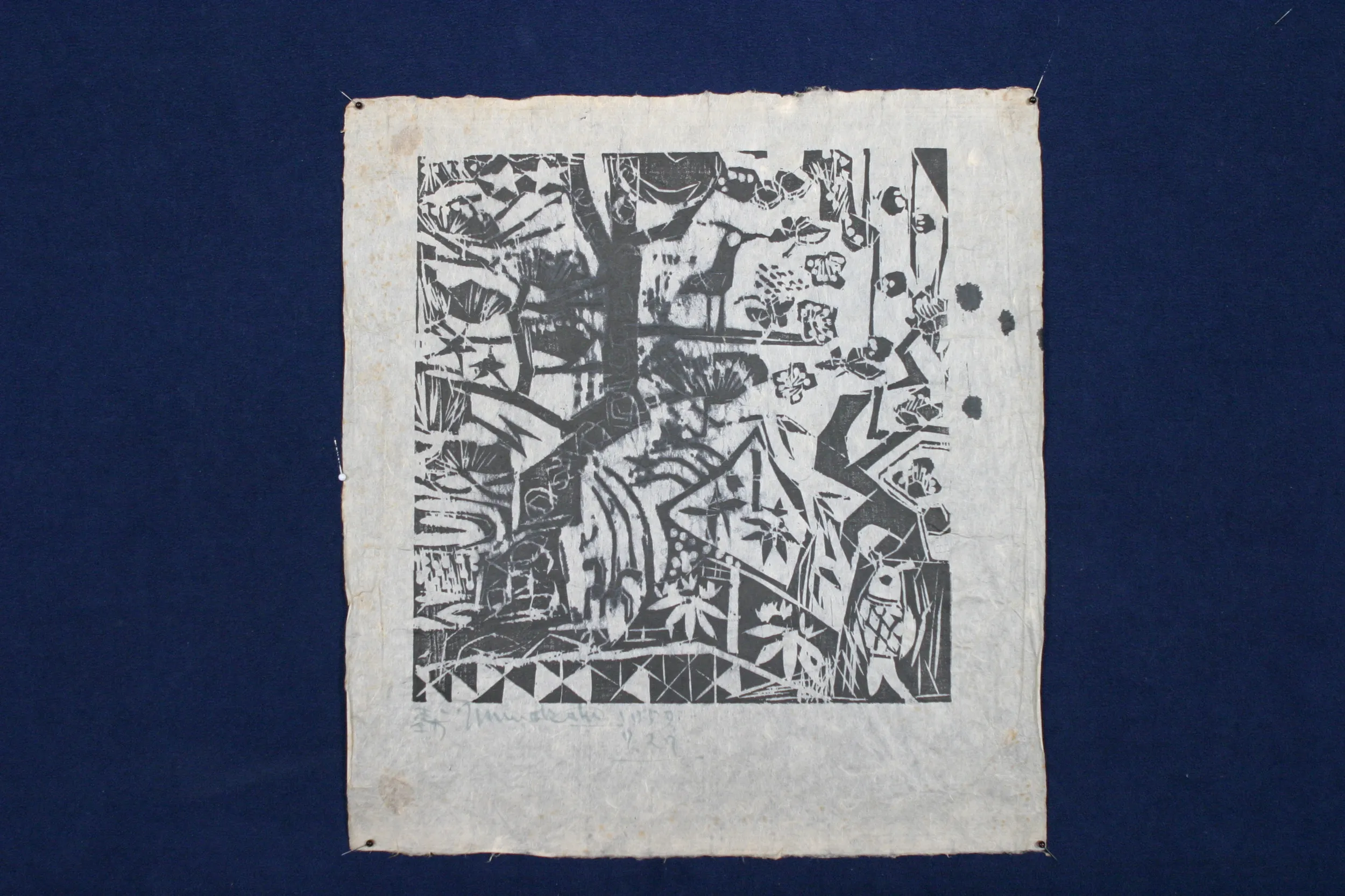

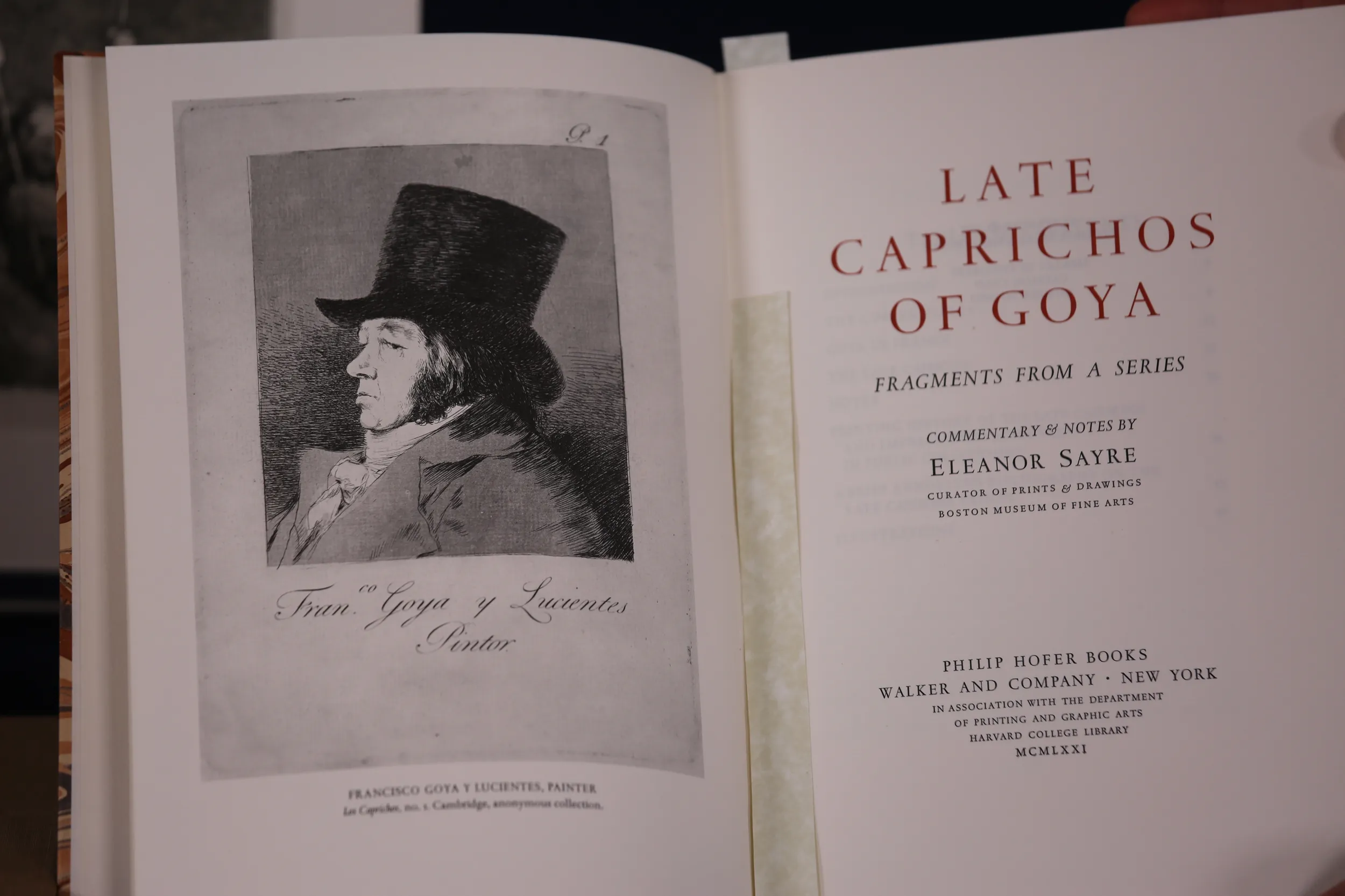

APPRAISER: You have six etchings here by the Spanish master Francisco José de Goya. He was working in the late 1700s into the early 1800s. And he produced this magnificent series of etchings around 1799 called “The Caprichos.”

GUEST: Ah, okay.

APPRAISER: All of which were about this size. And a lot of them condemned what was happening in Spain at the time with the monarchy, and with the disparity in wealth with some aristocrats and a lot of the poor. And Goya parodied this in “The Caprichos” and he only put out a handful of sets. And then fast forward about two decades later in the 1820s, he had moved into self-exile

GUEST: Uh-huh.

APPRAISER: from Madrid to Bordeaux in the south of France,

GUEST: Uh-huh.

APPRAISER: basically to stay out of trouble. This was at the end of his career.

GUEST: Mm-hmm.

APPRAISER: And it's at this time that he produced these images. And they're called "The Late Caprichos of Goya" because they kind of match the size of “The Caprichos” that were made in 1799, his first printed images. But he made these in Bordeaux, and he actually made them on only three plates.

GUEST: Oh.

APPRAISER: So each plate had one of these images on both sides.

GUEST: Uh-huh.

APPRAISER: And he only printed a handful of them in his lifetime, only several lifetime proofs are known of these. After he died, the plates went to his son, his only surviving heir,

GUEST: Uh-huh.

APPRAISER: and in the mid-1850s they went to an English ambassador to France, who brought them back to London. And they found their way onto the London art market, where in the 1930s they were purchased by a Boston philanthropist book collector whose name was Philip Hofer.

GUEST: Okay.

APPRAISER: Who donated his collection to Harvard Library. And when he donated them, he had this set printed and published in 1971. So he had them printed by a New York printer whose name was Emiliano Sorini, and you can see Sorini's stamp

down here, that "E.S."

GUEST: Oh, okay.

APPRAISER: It's a blind stamp.

GUEST: Right.

APPRAISER: and you can see Philip Hofer's initials on the right of each.

GUEST: Right.

APPRAISER: So Hofer had these printed in a set of 150, and this is number 96, so there's only 150 of these known, and they were made for friends of the Library and other institutions. Within the edition of 150, there were 25 deluxe editions. You don't have one of those,

GUEST: Okay.

APPRAISER: but the 25 deluxe editions actually had two sets of the six etchings printed.

GUEST: Oh, okay.

APPRAISER: Any idea what they're worth?

GUEST: No. I tried to look it up online and I saw a wide range.

APPRAISER: Yeah.

GUEST: I saw some of the individual prints, but I was hard-pressed to find a collection.

APPRAISER: Yeah.

GUEST: I did see one and it was $1,000 to $3,000 is kind of the range that I saw, so I have no idea, yeah.

APPRAISER: Yeah.

GUEST: Now even though they're printed much later, posthumously, very few prints were made of these in the 1800s.

GUEST: Uh-huh.

APPRAISER: this is the only way you see them.

GUEST: Oh, really? Okay.

APPRAISER: And, at auction, I would expect the set, in the condition that you have them, which is very good, to bring between $5,000 and $8,000.

GUEST: Oh, my gosh. (laughing) You're kidding.

APPRAISER: No. It's a wonderful group you have by one of the, you know, the most famous Spanish artists of the late 1700s, early 1800s.

GUEST: Wow.