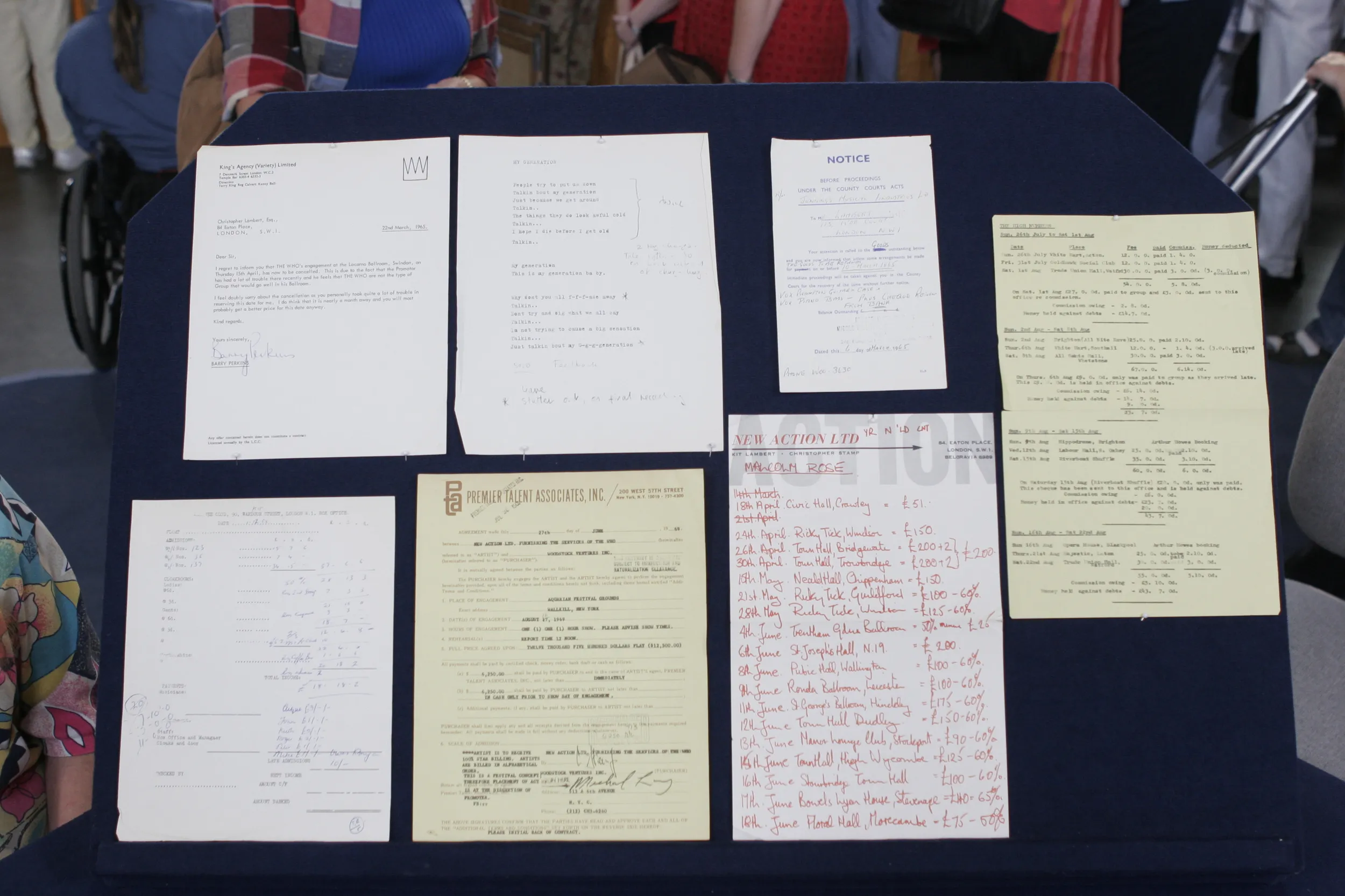

Holocaust Survivor's Archive, ca. 1942

GUEST: My mother was born in the town of Sosnowiec in Poland in February 1926. She was the child of religious Jews. World War II began for her in September of 1939. And in February of 1942, shortly after her 16th birthday, my mother was summoned to the train station at 4:00 in the morning, and under armed guard, she was sent to a labor camp in Czechoslovakia called Oberaltstadt. A few months after her arrival, she was able to write home to her parents, and that postcard has survived.

APPRAISER: This is the front side of the postcard. Where is this?

GUEST: It's the area around the Oberaltstadt camp in Czechoslovakia. The postcard is actually written in German. It's not in a handwriting that we recognize as hers. What we believe is that she asked someone at the camp to write the postcard for her in German, which may have been what the German censors wanted her to do. She writes, "My dearest and unforgotten parents. "I received your postcard and read it with "lots of joy and tears. "Dear parents! "I wonder why you don't write more often. "I wonder what is going on. "I heard that this week was terrible for you "with the relocation. Many people left Sosnowiec." And she goes on to say how she had heard from a friend of hers who also went to the camp with her that her parents were okay, which alleviated her concerns as to their welfare. And then also, in the, at the bottom of the postcard, she sends her greetings to all of her brothers and sisters who were still at home. Because my mother was the first one from her family to be taken from home and sent to a slave labor camp.

APPRAISER: Basically, what was happening there is, the Germans needed labor. They were working for textile companies, for manufacturing companies, and Jews and other non-Aryan people, they just pulled in slave labor. Now, why don't you describe these two photographs?

GUEST: Well, the bottom photograph is a picture of my mother that was taken shortly after the war began. In that photograph, she was approximately 13 or 14. It was either taken late in 1939 or early in 1940. And the upper photograph was the photograph that was taken in 1942, while she was at Oberaltstadt. They took her on an excursion to the countryside, and she had her photograph taken with some of the German overseers from the slave labor camp. And it was something that was very important to my mother, because she carried it in her wallet for years after the war. The photograph is cut out in spots, because my mother was told that if she was photographed with Aryans, that she could be punished, and the Aryans could be punished for having their photograph taken with a Jew. There is a part of the photograph that's cut out that shows a man standing there. We're not sure, but one of the stories that my mother told was, when she was at the factory at Oberaltstadt, one day, the SS came in and announced that any workers who were not assigned to a machine would have to go for resettlement. At that point, all the Jews in the camp-- and this was a camp of all Jewish girls-- knew what resettlement meant. It meant they might be sent to a death camp. And she went up to this foreman, who was over six feet tall, and my mother was under five feet tall. And she said, "I looked up at him and I said, 'Am I going to have to leave also?'" And this foreman said to her, "Not you, you're one of my best workers." And he walked her over to a machine, and he just said, "Look busy." So it's possible that this gentleman or another gentleman may have been instrumental in seeing to it that my mother was not sent for what they called resettlement.

APPRAISER: Now, the blouse. How did that come about?

GUEST: I think she wanted to have a change of clothes to have so that she could blend in with the crowd more if she, she left the camp. She always returned, obviously. She didn't want to get, to get punished or get caught outside the camp grounds. So she fashioned a blouse for herself out of material that she found on the factory floor. In May of 1945, when Oberaltstadt was liberated, she knew that her older sister and her younger brother were at a nearby labor camp called Langenbielau. And she left the camp with other girls and went to the train station. And she was actually reunited with her older sister and her younger brother at the train station. My mother's oldest brother survived the war. Her parents and her younger brother and sister, whose names were Sarah and Akiva, they were killed at Auschwitz. My mother never had an exact date for when it was that her parents and her younger sister and brother perished. My mother passed away in 2014 and we found these items. There are a lot of times when I look at these items, and I talk about these items, when I can't help but become very emotional. Because nowadays, to think of someone who had just turned age 16, a young girl who should be going to dances, going out on dates, is basically fighting for her life.

APPRAISER: I mean, it's, it's... (voice breaking) ...just a very difficult...

GUEST: Yeah.

APPRAISER: One of the things that is incredibly difficult is, part of what we do here is put a monetary value on something. And you say, "How can you put a monetary value on this?" But the reality is, either in an estate, the I.R.S., if it's being given to a university or a museum, people put a value. And also for insurance. There's the famous quote, "People who do not learn history are doomed to repeat it." And you need items like this to learn about it. Also, on the blouse, there are very, very few three-dimensional objects that came out of those camps. A value on this, either for insurance or donation, would be $10,000. Although the real value is in how it can be used to teach the future generations.

GUEST: For us, it gives us a tangible connection with a past which was basically stolen from us by, by the Nazis.

$10,000 Insurance

Hamilton Township, NJ

Photos

Featured In

episode

Grounds For Sculpture, Hour 2

Garden State treasures bloom at the Grounds For Sculpture, with finds up to $125,000!

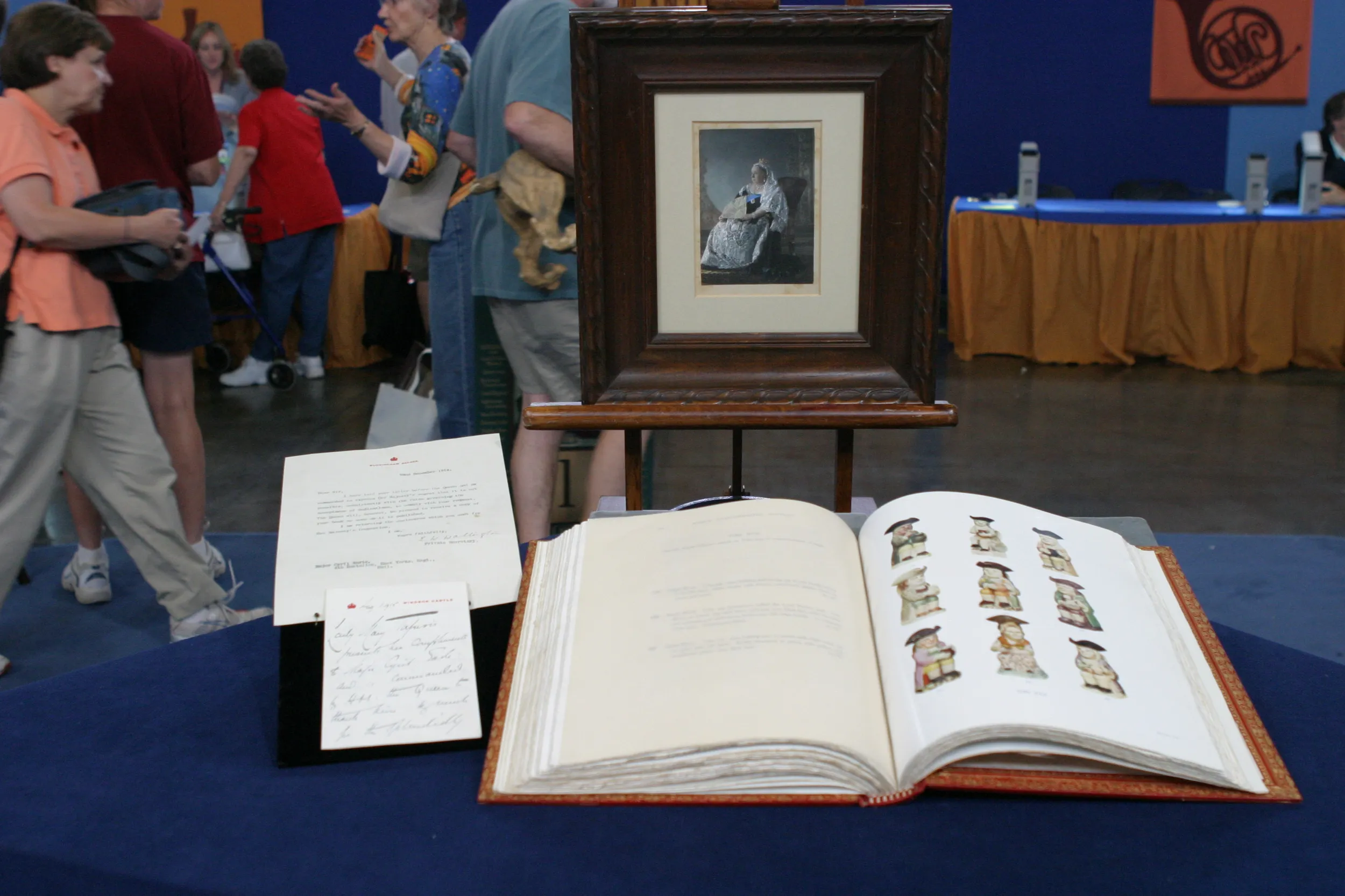

Books & Documents

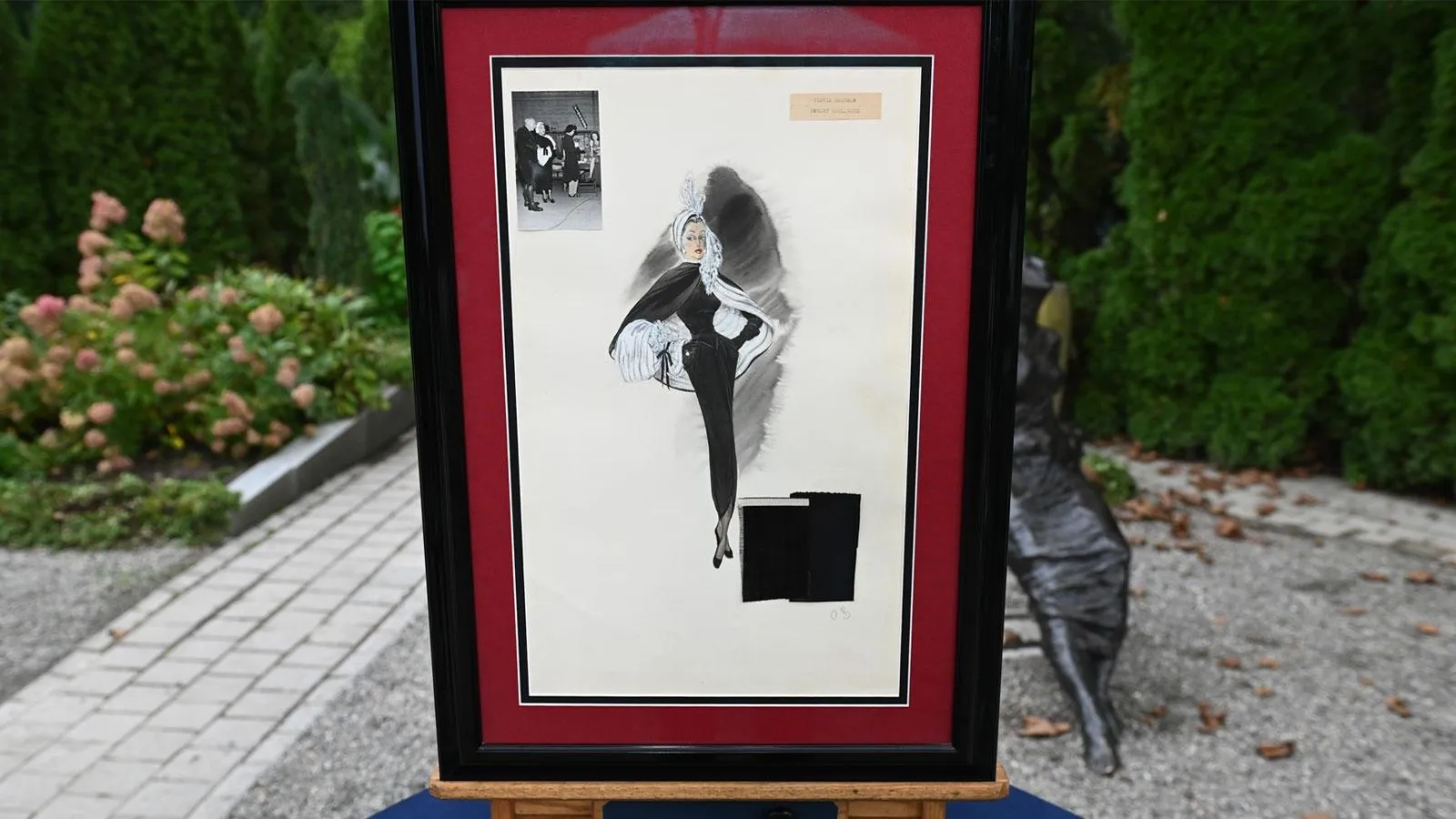

appraisal

appraisal

appraisal

Understanding Our Appraisals

Placeholder