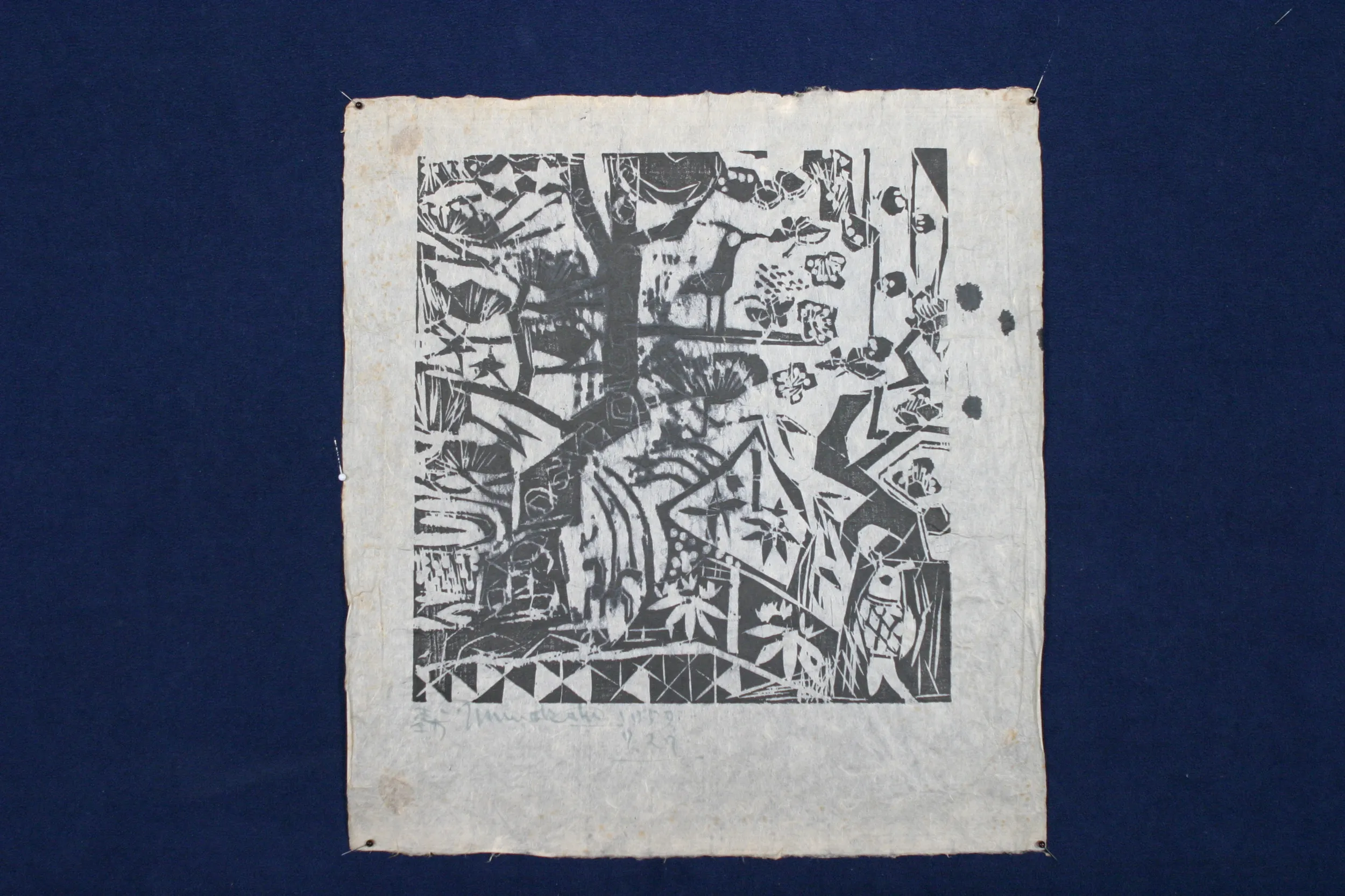

GUEST: So this is a painting by John Haberle, my great-great-grandfather. He was born and raised in New Haven, Connecticut, and he was mostly known for his trompe l'oeil work. Um, later in his life, he started to lose his eyesight. So that explains the lack of precise painting. (laughs) And this is a book of some of his sketches. His daughter Vera started to dismantle his sketchbooks, so we put some of them in these plastic sheets. But other than that, this has just been in our living room since, um, my mother retrieved it from his house in New Haven in the 1970s.

APPRAISER: We do think of Haberle as an artist of trompe l'oeil pictures. And trompe l'oeil literally means "paintings that fool the eye." He's in a long line of the tradition of trompe l'oeil. People think of Harnett and Peto, who are the great American trompe l'oeil painters, and he's really the generation after that. Even though this picture is not in his very precise style, it still conveys that idea that so many of his pictures did. It's a very humorous subject. It's a very appealing subject. Its value is not going to be quite the same because people, obviously, want to collect his very precise pictures. One of the reasons that his trompe l'oeil pictures can be as costly as they can be is, as you say, he had a relatively limited output because of his declining eyesight. But you've also brought these sketchbooks. This is only one of several that you brought. We see a lot of examples of figure drawings. Again, not what he's quite so well-known for, but dated mainly in the 1880s, which was his heyday. It was when he was doing all of his most famous work. And his drawings do turn up on the market, as well. It brings up the question of sketchbooks, and whether they should be intact or whether it's okay if they're taken apart. There's a lot of controversy about that amongst the sort of art historical and art dealing world. People who are really interested in art history would love to see them all kept together.

GUEST: Okay.

APPRAISER: And ideally, that would be the best situation. But from a commercial point of view, people who are in trade and dealers will often take a sketchbook apart because they can sell them more easily as individual sheets. Fortunately, you still have it, and that's the most important thing. In terms of value, I would think, uh, an insurance value on your painting of approximately $30,000.

GUEST: Okay.

APPRAISER: And the drawings, you have quite a number of them. They sell anywhere from $100 to about $400, depending. If we took an average of, say, $200 apiece...

GUEST: Right.

APPRAISER: ...30 would be worth approximately $6,000. So I'd say you have at least that. And I didn't count up all the drawings, but maybe even more than that

GUEST (chuckles): Right.

APPRAISER: And I, I just think you're incredibly lucky to have it.

GUEST: Thank you so much.

APPRAISER: You're welcome.