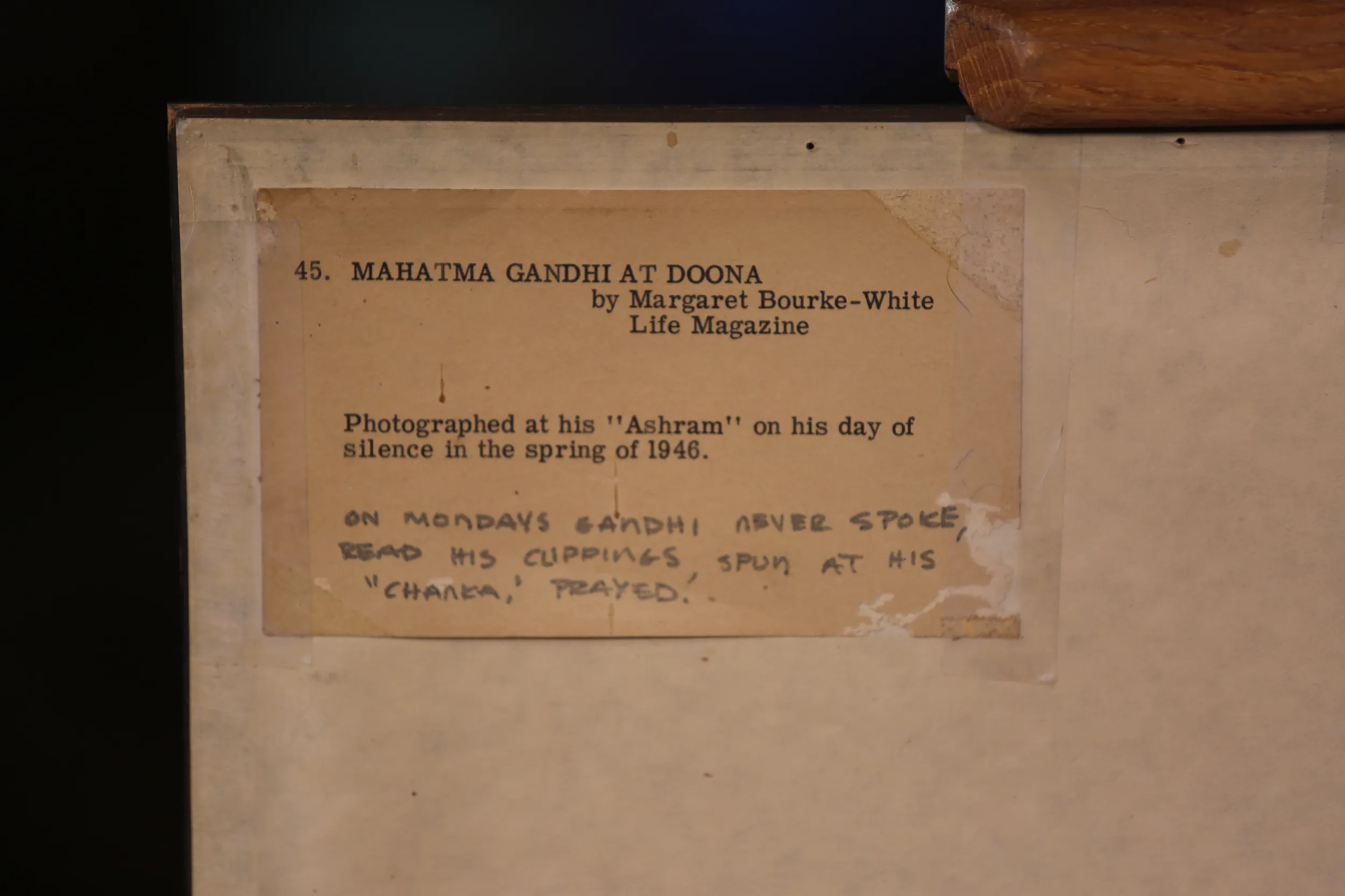

GUEST: I inherited it in about 2012, when my mother passed away. She'd gotten it from my stepfather. He moved into our house in about 1964, and I fell in love with it. When it came to me, I was pretty excited because my mom had thought it should just go to a museum. She asked us what we wanted and I said the only thing I want is the Gandhi. After she was gone, I was sitting around with all my siblings and we were bequeathing things to each other. They said, "Well, you're the yogi," because I'm a yoga teacher, "So you should have the Gandhi," because they all knew how much I loved it. I looked up the photographer and I was very interested to find it was a woman photographer. For her to be a woman photographer going into his inner chambers and photographing him, I'm sure he had something to say about that, because women in 1946 in India were basically chattel. And so for a professional woman, American woman, to come in to his kind of inner sanctum, and this was his day of silence, as, as written on the back of the photo-- he'd spent a day each week in silence just reading articles and working on his chakra or his spinning wheel. I know that it was chosen as one of "Life" magazine's 100 top photos of all time. I know it was, this picture was taken in 1946. So that was about two years before he was assassinated. It's just like being in the room with him, or, you know, with somebody who was there with him. For me, it really touches my heart.

APPRAISER: How did your stepfather acquire this photograph? Do you know?

GUEST: I don't really know. He, he was an Episcopal minister and he was in... This was in Northern California, in the East Bay, and he was involved with the Civil Rights Movement. He really looked up to the peacemakers. He had it when he came into our home.

APPRAISER: Gandhi was one of the most important men of our generation. And for her to be able to capture this is just sensational. Of course, it ran as a big story in Life magazine. Margaret Bourke-White was born in 1901 in New York. She went on to, eventually, Cornell University and got a bachelor of arts degree. She moved to Cleveland, opened up a studio that specialized in architecture and industrial photography. And then became the first woman journalist for Life magazine at the inception of, of Life. She did a photo essay on the building of the Fort Peck Dam, and her photograph of the Fort Peck Dam was the first photograph on the cover of the first Life magazine.

GUEST: Oh, wow!

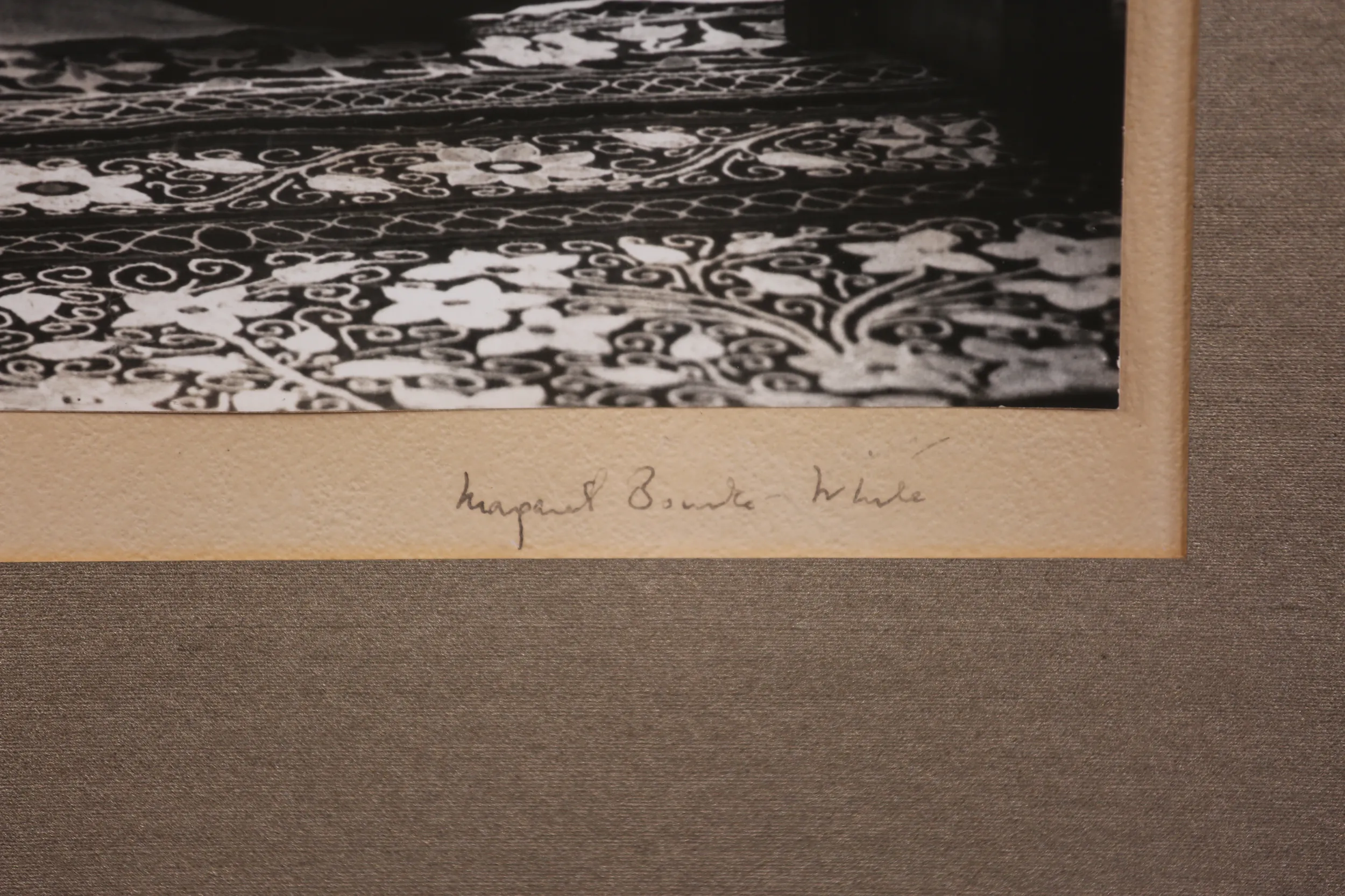

APPRAISER: In the '50s, she got Parkinson disease and it slowed her career down. She died in 1971. The signature's on the mat.

GUEST: Right.

APPRAISER: It's, it's in very good condition, but I would definitely get rid of this mat board and get archival mat board. Also get some archival either glass or plexi that will give it U.V. protection. You have any idea of what the value of this photograph might be?

GUEST: Not really. I contacted one gallery online and they had never handled an original print of her lifetime. They'd only handled, after her death, authorized by her estate, prints. They said that they sold the authorized prints for $25,000.

APPRAISER: Well, the modern prints of her work sell anywhere from $3,000 to maybe $12,000, $15,000. We know that this is an early, early print, possibly a vintage print. We know that this was the frame that it came in, and the mat board on the back of it has the sticker from the framer and there's no ZIP code on it.

GUEST: Right.

APPRAISER: And in the telephone numbers, there's letters. So we know it's probably prior to probably somewhere in the '50s.

GUEST: Mm-hmm.

APPRAISER: And it could be 1947. We don't know. Right. But you very, very, very rarely see this photograph printed this early.

GUEST: Mm-hmm.

APPRAISER: I would give it a retail value of between $40,000 and $50,000.

GUEST: Oh, wow. Wow... (laughs) That's great.

APPRAISER: Well, thank you so much for bringing it in. You really...

GUEST: Well...

APPRAISER: You really did make my day.

GUEST: Thank you.