GUEST: I brought a collection of photographs that were taken by my great-grandfather, whose name was Arthur Ludwig Princehorn. And he was a professional photographer, and he took these in 1901 at Glen Island, New York. There was a resort there, and during the summer, they had a group of Indians there for, like, a traveling show. I believe Sioux Indians from the Rosebud Reservation in South Dakota. And my grandfather took numerous photographs of them over the course of the summer, and we have a few hundred of those left. And then I...

APPRAISER: A few hundred?

GUEST: Yes.

APPRAISER: Okay.

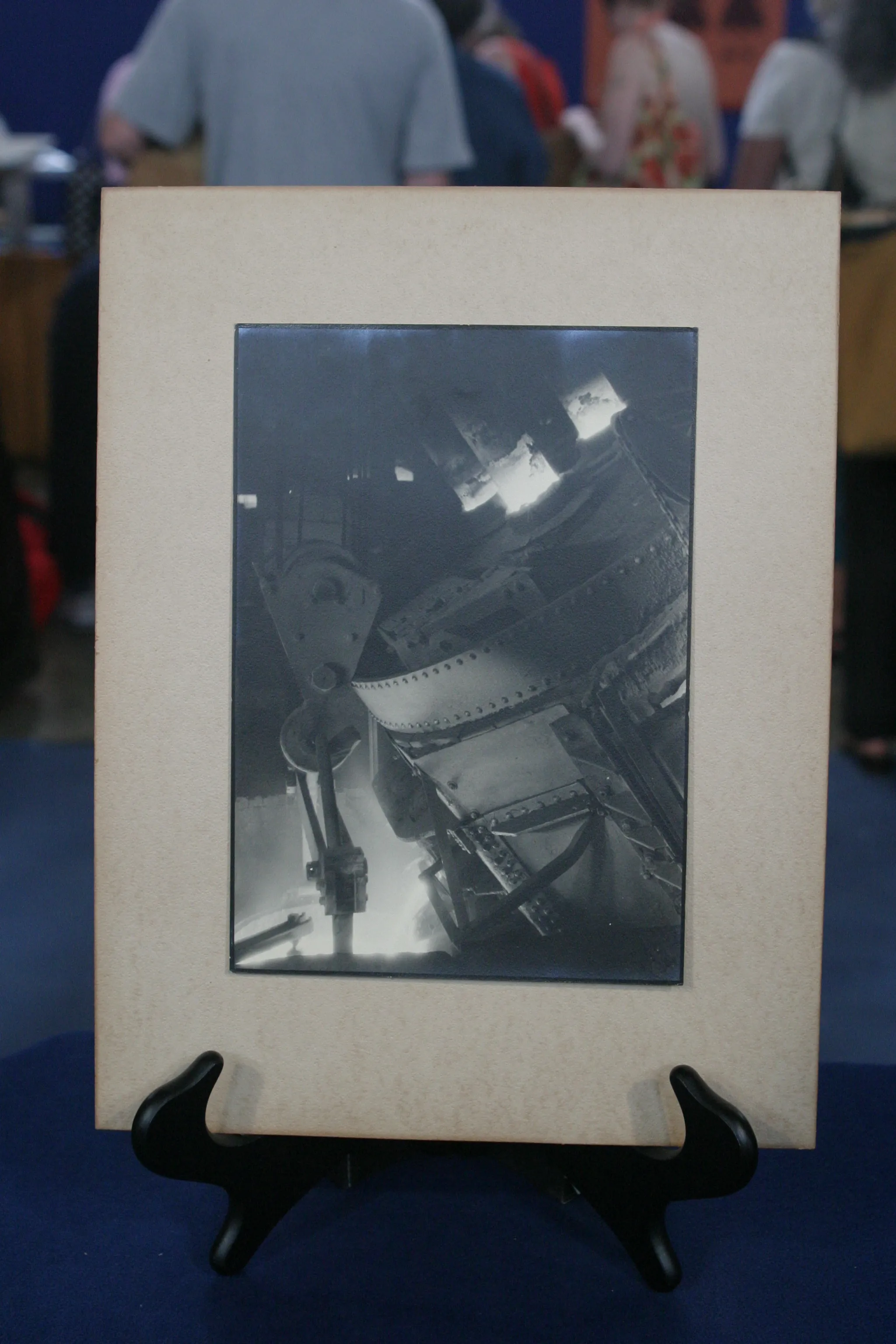

GUEST: And we found a few of them framed, but most of them are just still loose. And I also brought a camera that my great-grandfather actually built so that he would have a more satisfactory camera for taking the pictures. So we believe that it's actually the camera that took many of the pictures that we have today. The family history is that my great-grandfather at one point showed the camera to the curator at the National History Museum, and that curator made a copy of the camera, and that copy was supposedly used to design the modern Graflex.

APPRAISER: It's not in very good shape.

GUEST: Okay.

APPRAISER: It's missing the lens and the shutter.

GUEST: Yes.

APPRAISER: But if indeed the camera is a prototype for a Graflex, you're talking $600 to $800.

GUEST: Okay.

APPRAISER: But the value of all this is it's an archive. In the late 1800s, the Indian wars had pretty much ended. All the fights were over. And there was a huge interest worldwide in what had happened in the American West. And a man, Buffalo Bill Cody, came along.

GUEST: Yeah.

APPRAISER: Buffalo Bill tried a Wild West show in the 1870s, and they tried again in the 1880s. It was a tremendous success clear through the '90s. By 1900, everybody who had shows was trying some little Wild West show, with horses and riders. All of a sudden, the world was changing, and there was a lot of nostalgia, and your great-grandfather was there with his camera.

GUEST: Yeah.

APPRAISER: These are Sioux Indians. It is Rosebud, but they're Brulé Sioux.

GUEST: Okay.

APPRAISER: And the Brulé Sioux in the 1870s were in Nebraska.

GUEST: Okay.

APPRAISER: There are some other bands of Sioux in here.

GUEST: Okay.

APPRAISER: He did photographs like this, standard portraiture. This one's great, because it's a group shot.

GUEST: Right.

APPRAISER: And it's Hollow Horn Bear in the middle, who's a very important Sioux chief in the 19th century.

GUEST: Okay.

APPRAISER: There are other photographs that, in my estimation, are probably more important because they document the show and they're action photographs.

GUEST: Right.

APPRAISER: This one here, which shows them on horseback. One man's firing off a rifle.

GUEST: Yeah.

APPRAISER: It looks like a Winchester. The other one shows a dancer, and the dancer looks like he's having a great time. These guys were paid to come do this. It was a warrior society.

GUEST: Mm-hmm.

APPRAISER: And it was a way for them to re-enact the past. The portrait shots are not that unusual, but these are beautifully done. There's 31 photos in here. 11 of them are large portraits, and the other 20 are small action shots.

GUEST: Okay.

APPRAISER: These individual photographs are signed, which helps.

GUEST: Yes, I think these are the only four that were signed, is the ones they framed.

APPRAISER: Oh, really? It needs to be kept together as a group.

GUEST: Yeah.

APPRAISER: You're not going to get rid of these things.

GUEST: No, never.

APPRAISER: This is so irreplaceable-- that probably kicks it up to $18,000 to $20,000 for insurance.

GUEST: My goodness gracious. My grandfather would have been thrilled.