World War II Prisoner of War Archive, ca. 1943

APPRAISER: Tell me about your father's personal experiences in World War II.

GUEST: Well, when the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, they also bombed Manila in the Philippines, but instead of going back to Japan, they took the Philippines and they took 100,000 people prisoners of war. My dad was one of those prisoners of war. He was in Cabanatuan prison camp in the Philippines and then taken on a hell ship to Japan, where he served as a prisoner-of-war slave laborer actually for the Mitsubishi Corporation in Japan. But he was in prison camp or as a "guest of the emperor," as he used to call it, for 39 months, and then returned to Spokane and ended up having a great life and lived to age 79.

APPRAISER: He spent the entire American participation of World War II, essentially, in Japanese captivity.

GUEST: That's right.

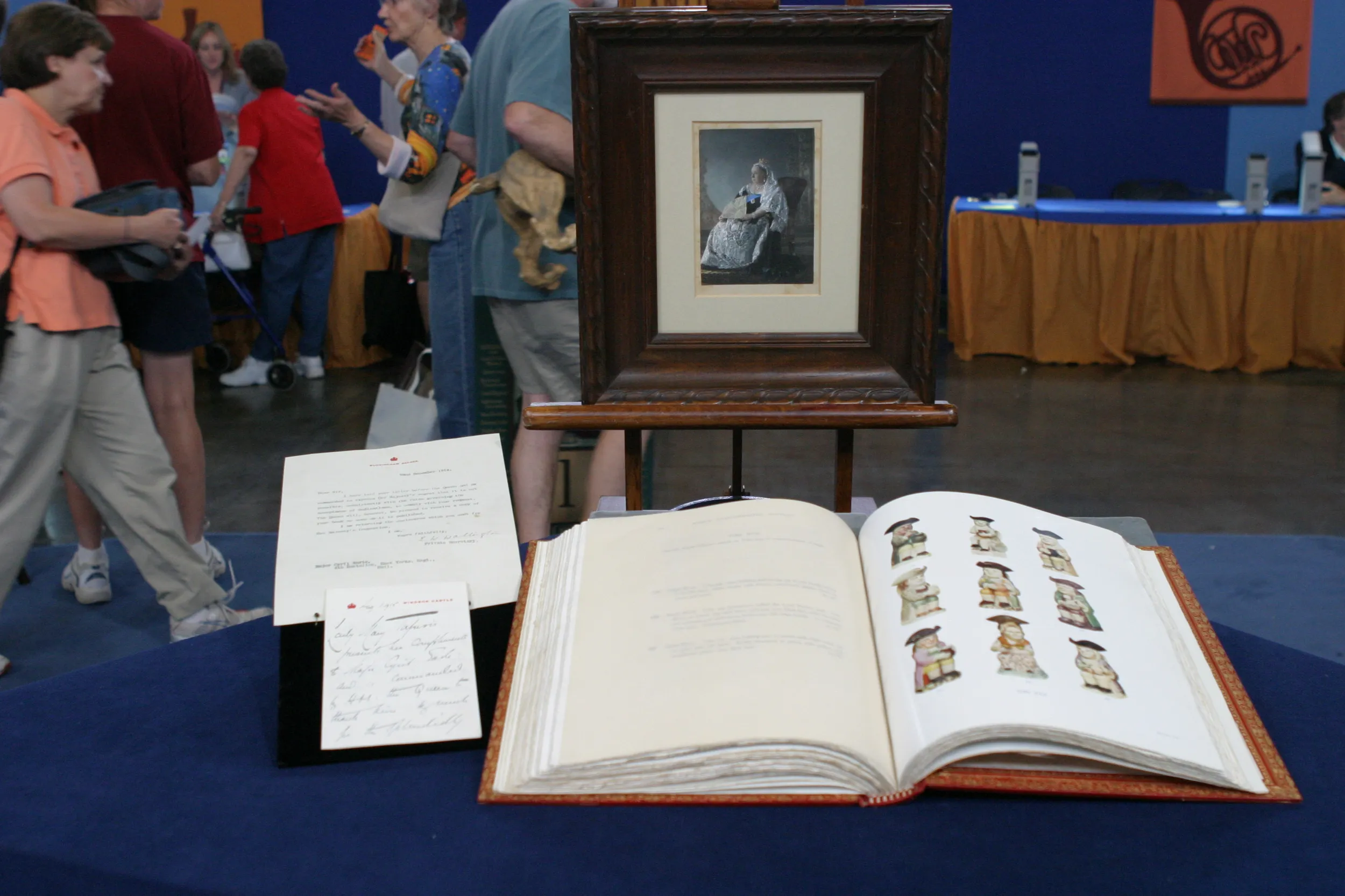

APPRAISER: Really, what we have here is an archive of his service, and he kept a diary of sorts, and it's what we normally call trench art. It's an art form that's best known in World War I, but it exists in World War II also. And in fact, this is a World War I mess kit. They continued issuing those into World War II. And what can you tell me about some of these?

GUEST: He joined the Marines in 1939 and went to Shanghai, China, with the Fourth Marine Regiment. And then they were sent to the Philippines in November of '41. When he was first captured, he was in Cabanatuan prison camp, and then as I said, he moved to Japan, went to Sakurajima prison camp and then ended up in Akenobe.

APPRAISER: And Akenobe's what we see on this little pipe also here.

GUEST: When they got cigarettes, they didn't smoke the whole cigarette; they took part of it and they smoked it in a little pipe to save as much tobacco as they could.

APPRAISER: People probably don't realize this, but the Japanese army planned on their soldiers accounting for a certain percentage of their daily ration from foraging, and so they weren't issued the entire calorie count that they needed for the day. They followed that same line of logic with the prisoners of war, although they were certainly not in a position to be able to go out and find food nearly as easily as the Japanese soldiers were. And so that accounts for a lot of the starvation and the problems that those poor folks had when they were in captivity. So really, this accounts for not only a diary, but this very mess kit is the one that was his daily link to living.

GUEST: On very meager rations as well.

APPRAISER: And in addition to that, it's also an address book of sorts.

GUEST: That's right.

APPRAISER: I noticed on the back here that there are several names. Did he discuss any of those fellows with you?

GUEST: He never talked about this experience very much at all, so I don't know who these people were, but these were friends of his that he wanted to make sure he knew where they were after the war.

APPRAISER: They clearly had some significance to him.

GUEST: Definitely.

APPRAISER: The guys who were physically able were taken to Japan and used as slave labor.

GUEST: Right.

APPRAISER: These are artifacts from his time in that experience. He's got his timesheet and then his identification tag from the Mitsubishi company.

GUEST: They had the same logo back then as they do today.

APPRAISER: What was he doing for Mitsubishi?

GUEST: He was in a copper mine, working the copper mine for Mitsubishi.

APPRAISER: So essential war material.

GUEST: Right.

APPRAISER: You've got some--a photograph here from Cabanatuan…

GUEST: Right.

APPRAISER: …of some of the individuals, and then we have your dad. This was...?

GUEST: Just after he got out.

APPRAISER: Just after he returned. And then this is his United States Marine Corps ID tag.

GUEST: That's right.

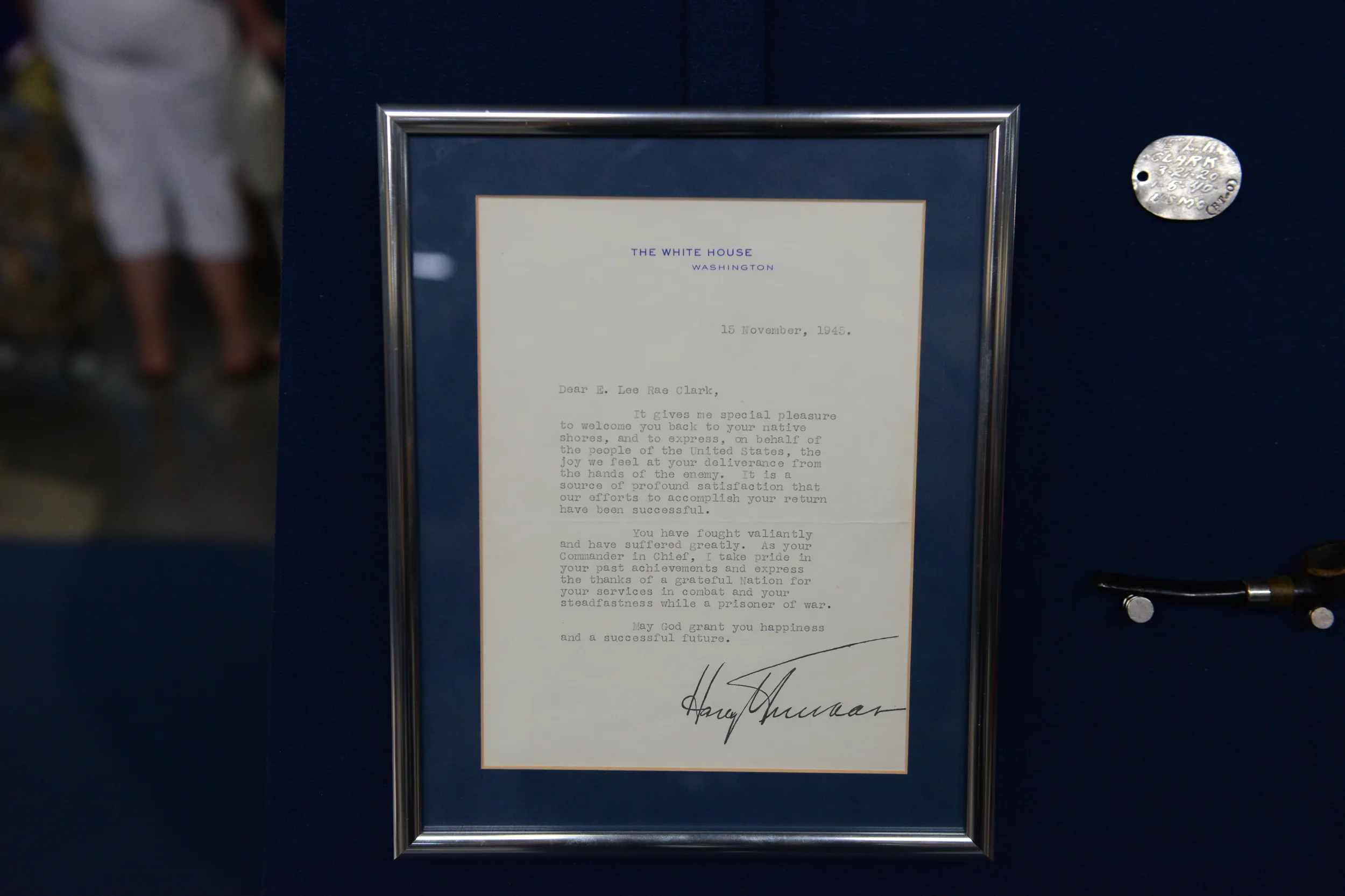

APPRAISER: And then this over here is something that he received after he got out.

GUEST: He did, dated November 15, 1945 from Harry Truman, a typed letter welcoming him back to his native shores and thanking him for his service.

APPRAISER: Tell me how your father came to be in possession of the Cabanatuan photographs if he was gone when the camp was liberated.

GUEST: Afterwards, a lot of the POWs from Cabanatuan got copies of these photos. He wasn't a part of taking the photos.

APPRAISER: You just have to wonder how they were able to take those photographs at a prison camp. I can't imagine that the Japanese were interested in having that documented.

GUEST: Not at all, but one man had a roll of film, the other one had a camera, and the roll of film didn't fit the camera, so they cut it in the dark room to be able to fit the camera. They took 15 photographs and then they buried the photographs and came back after the war. A Ranger battalion came back to Cabanatuan and dug them up.

APPRAISER: Prisoner-of-war material is very uncommon on the market. Not a whole lot of it survives. Very rarely do we find any souvenirs from their experiences at all. The daily drama of a struggle for existence is a very compelling story, and it's something that there is a distinct market for among collectors and museums that are interested in World War II history. For the group as a whole, I would expect to see a retail value of $3,000 to $3,500.

GUEST: Interesting.

APPRAISER: Of that, the letter accounts for approximately $1,000 of the price.

GUEST: Very interesting, thank you. It's something in our family, we'd never sell it, obviously-- it's real close to our hearts—but—uh-- that's interesting to find out.

$3,000 - $3,500 Retail

Photos

Featured In

episode

Special: Junk in the Trunk 6 (2016)

Travel to all six cities of this season for never-before-seen appraisals!

Books & Documents

appraisal

appraisal

appraisal

Understanding Our Appraisals

Placeholder