A Match Made in Heaven (Or at Least New York)

How subsequent testing told a different story about this monumental "marriage."

Jun 8, 2020

Originally published on: Oct 29, 2007

June 8, 2020: Update from Appraiser Leigh Keno

Appraising this monumental piece at the Milwaukee ROADSHOW back in July 2006 was definitely memorable. On the day, my brother and I had just 20 minutes to examine the piece, so we were actually still assessing it while conversing with its owner, Clarence, with the cameras rolling! Thanks to the piece having been sent to conservator Alan Miller for closer inspection a few months later that year, we subsequently learned that Samuel Prince made this a desk in the 1770s, then followed that up perhaps 10 years later by crafting a bookcase section to sit on top — complete with an elaborate basket-carved cartouche in its pediment.

Unfortunately, today's market for 18th-century American furniture is considerably lower than it was back in 2006. Also, in general, Chippendale-era New York slant-lid desks are slightly wider than desks made in other regions, creating additional considerations both of visual appeal and available space for certain buyers. And the fact that a complementary bookcase was made to enhance this piece for its owner in the late 18th century is — while a fascinating story to someone like me — for other collectors, possibly an enigmatic one that would complicate the decision to invest.

While researching New York Chippendale desks recently, I was surprised to find that Clarence's desk with bookcase had sold at Northeast Auctions on October 29, 2017, for the bargain price of $12,600 (including buyer’s premium). I only wish that I'd known about the sale, because at that price — or perhaps a bit more — I would have loved to have the piece myself! Someone got a great buy on a rare, labeled Samuel Prince treasure and that in itself is a towering example of why this field continues to be so exciting!

— Leigh Keno

(Original article published October 29, 2007)

A Match Made in Heaven (Or at Least New York)

BY DENNIS GAFFNEY

A ROADSHOW GUEST named Clarence arrived at the Milwaukee event on July 29, 2006, eager to know something crucial about his impressive 18th-century mahogany secretary: Was the set, composed of a desk and a bookcase mounted on top, designed as an original pair, or was it cobbled together later from two well-matched but different pieces?

In the furniture trade, such artificially joined pieces are called "marriages." And as a rule marriages are less valuable than original pairs, in large part because marriages are often made for the purpose of fooling buyers. A longtime antiques collector himself, Clarence knew enough to understand that such a handsome and well-made secretary — if an original — could command as much as $300,000 in an antiques shop. But if it was a marriage, then that enormous value would be considerably less.

The Keno brothers with Clarence and the secretary, during taping of the Milwaukee Antiques Roadshow event in July 2006.

A Detective Story

Clarence's question was fairly simple, but the answer was not, and it took a few top-notch appraisers as well as a good number of months to find out the origins of the antique he had inherited before World War II. What unfolded serves as a remarkable insight into how antiques appraisers practice their trade. Far from an exact science, it is most often a zigzag of detective work — an attempt to solve mysteries created by the haze of time. And as with all good mysteries, in this case one clue led to another until the full story was revealed.

In Milwaukee last July, Leigh and Leslie Keno, both experts in early American furniture, had barely more than 20 minutes to examine the secretary before taping began for their appraisal segment with Clarence. But when the time came, they were both raring to go.

"We're smiling," Leigh told Clarence on camera, launching into a tag-team appraisal alongside his brother Leslie. "Jumping up and down, drooling and everything — right Les?" Leigh called the piece a "New York masterpiece" and a "classic example of New York 18th-century design and cabinetmaking." And Leslie described the elaborate finial — an intricately carved basket filled with flowers and nuts that sits atop the bookcase pediment—as "the cherry on the sundae." In sum, the Kenos agreed that the secretary, with its beautifully matched desk below and bookcase above, was an exquisite original.

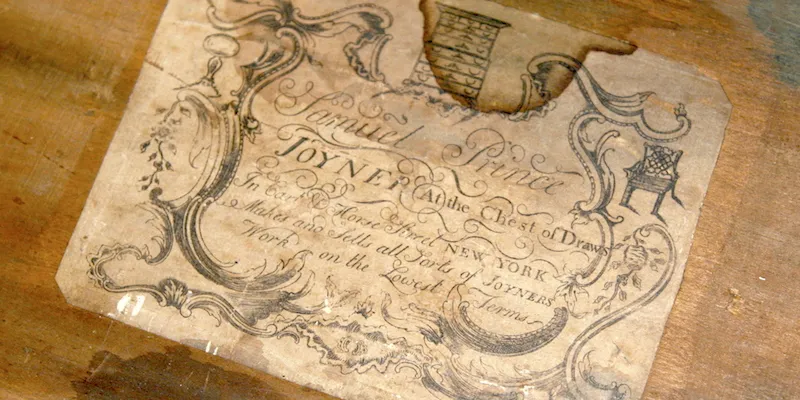

Leigh and Leslie were also pleased to make a find that's extremely rare in such an old piece of furniture: the original maker's label still glued to the inside of the top desk drawer. The secretary was crafted by Samuel Prince, a well-known New York furniture maker from the late 18th century. And given that the top and bottom pieces seemed so closely matched in finish, style, and proportion — the mahogany door panels on the bookcase closely echo the distinctive grain of the desk — the brothers thought it very unlikely that the secretary could be a marriage. Even the brass hardware was just as you'd hope to see. In short, they agreed Clarence's piece was an extremely fine original.

"Because it is not a marriage," Leslie said in the lead-up to the appraisal value, "[with] the condition... the proportions, the wonderful finish, [we think] that the estimate on this piece would be $150,000 to $200,000." Leigh added that on a good day it might sell for as much as $250,000 retail. If the set were a marriage, Leigh said, its value would plummet to the $20,000 range.

A Caveat

But the Keno brothers' assessment didn't close the book on this story. "Now I want to tell you one little thing," Leigh added near the end of the segment. "To be 100 percent sure, if I had this in my shop, I would actually get something called a microscopy done." It only takes about three days, he added, plus it's conclusive. Later, Leigh explained that when you're dealing with such potentially large values, "you have to do the research. And you can't do that in 20 minutes."

In the antiques business, microscopy refers to a microscopic analysis of a very small sample of wood from a piece of furniture to determine the make-up of the finishes that have been used. Leigh recommended it in this case because it could compare the finishes from the secretary's top and bottom to see if they bear the same finish applied at the same time.

But after Clarence got home, he discovered that a microscopy would potentially cost $6,000. "I wasn't going to do that," he said.

A Second Opinion

Instead, a few months after the Milwaukee event, Clarence shipped the secretary to Alan Miller, another expert in early American furniture, based in Quakertown, Pennsylvania. Miller kept the piece for a few months, disassembled parts of it for further inspection, and ultimately sent a written report to Clarence in September 2007, about a month before the segment was to air. Miller agreed with the Kenos' opinion that the piece is not a marriage. In fact, he said, the chances of finding such a large bookcase from this period that matched such a large desk were "ridiculously unlikely."

But Miller also had the benefit of time to scrutinize the piece more closely than the Kenos could, and was able to make a number of specific observations. He examined the wood on top and bottom to see if any identifying tool marks matched the bookcase to the desk, but couldn't find any that did. He noticed that the frame-and-paneled back of the bookcase is of a kind "usually associated with a slightly later date than the desk." After removing the top piece from the bottom, Miller also concluded that "the desk, conceptually, is a desk, not a secretary base." The sharply angled lid is also more typical of a desk, he noted. Moreover, in secretaries, the part of the desktop that will be concealed by the bookcase that sits on top is almost always made of a secondary wood. In this case, however, the secretary has a solid mahogany desktop, suggesting it was made as a stand-alone desk before it ever became the lower half of a secretary.

"My feeling," Miller concluded, "is that the most simple and most likely explanation of this piece of furniture is that it was made in stages and upgraded, the same way a house grows with added wings and remodeling. It tells a fascinating story about real people's lives and aspirations." The original owner might have had the bookcase made later because he was better able to afford it, Miller says, or because of a bigger room he had to display the piece in. In other words, Miller's conclusion is that the secretary does not represent an original pair, and yet it is not a marriage either. "A marriage often happens in a fraudulent way in the antiques business, and that's not what happened here." Still, he says, add-on pieces such as Clarence's are rare enough that there isn't even an official term to categorize them.

A Finial for the Ages

And there was one final surprise: Miller also recognized the finial crowning the bookcase. "I... believe it was made by the great Philadelphia carver Martin Jugiez," Miller wrote to Clarence. "The ornament, while sketchy and rapidly done, demonstrates Jugiez's remarkable fluency." For Miller, himself a Jugiez expert, this is a first; he said he has never seen a Jugiez carving on a New York piece. "Usually the local trade would supply everything," Miller said, speaking of 18th-century New York furniture. He suspects that the finial might be a rare example of a contemporary Philadelphia woodcarver breaking into the New York furniture market.

Back to the Kenos

A few weeks before this segment's October 29 airing on PBS, we contacted Leigh and Leslie to fill them in on Alan Miller's in-depth examination of Clarence's secretary. They found his theory both plausible and intriguing.

"I've seen several instances where an 18th-century desk has been upgraded in the period," Leigh said. "It's still an incredible piece. If it wasn't made in the same shop, I'd say it was made from a shop working at the same time. And I'd still say it's worth in the six figures, in the range of $100,000 retail, conservative. It still is one of the most exciting pieces of American furniture I've had the pleasure to appraise."

Yet the detective in Leigh still believes there's one more clue that, if gathered, could weigh heavily in the balance. "The microscopy on the surface would still be a nice thing to have," he says.

Editor's Note: This article was updated on November 14, 2007, to correct an editing error. The owner of the secretary prefers to be identified as Clarence.