Buying and Selling Native Artifacts

For collectors interested in Native American artifacts, there are some very important guidelines to bear in mind.

Jan 19, 2004

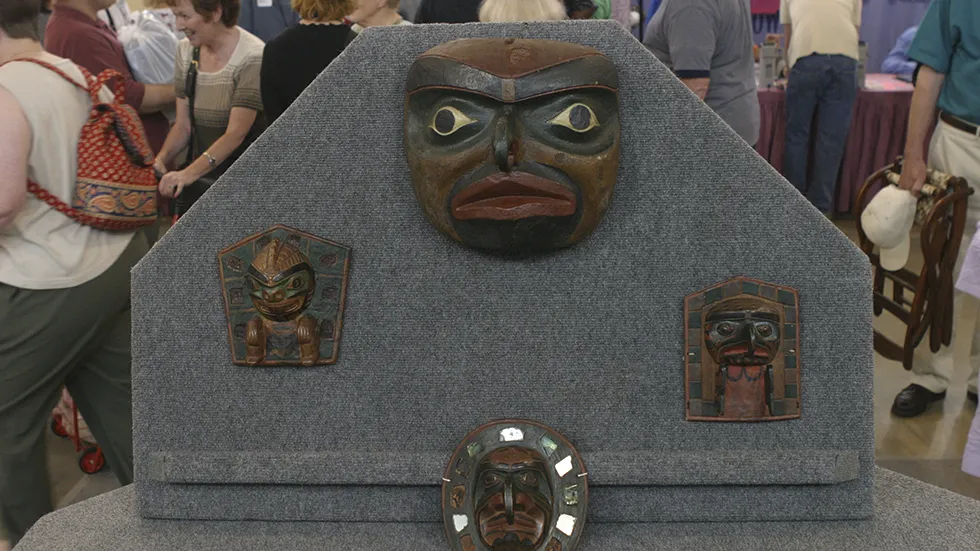

At the Chicago, Illinois, ANTIQUES ROADSHOW, a man brought in a collection of Northwestern masks crafted on the north end of the island of Vancouver in Canada. The masks were made by carvers in the Native American group once called the Kwakiutl, who are now known as the Kwakwaka'wakw.

As do many Native American objects, these masks raise an important question for all collectors of Native American objects: When is it legal for individuals to buy and sell, or even own, such Native American objects?

The question is a simple one, but its answer is complicated, requiring a careful reading of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA).

NAGPRA is a federal law passed in 1990 that provides a process for museums and federal agencies to return certain Native American "cultural items" — human remains, funerary objects, sacred objects, or objects of cultural patrimony — to lineal descendants or Indian tribes. Museums and federal agencies are almost always the ones challenged or prosecuted under the law.

Related: Safely Collecting Indian Artifacts

The law, however, also forbids the buying and selling of these particular objects on the market — which is where the law applies to individual collectors. Dr. Paula Molloy, the NAGPRA public affairs officer for the National Parks Services National Center for Cultural Resources, points out that in most cases it is legal for people to own such objects. That would mean that the man in Chicago who brought in the masks, which he had inherited from his father-in-law, had not violated NAGPRA by having the masks in his possession. The owner could also sell the masks legally as long as they don't qualify under the NAGPRA law's definition of cultural items.

Other objects, Dr. Molloy says, should cause individual buyers to back away from a purchase. "If you're looking at a funerary item, it should raise a red flag," Dr. Molloy cautions. "If it came from federal land or the reservation, it's the property of the federal government or a tribal government — you should stay away from that as well. As with anything, knowing where an object came from and how a dealer got it is the key for finding out whether it falls under NAGPRA." Similar caution is suggested by Bruce Shackelford, an independent San Antonio appraiser and consultant who deals with the history of the American West. "If some dealer says, 'This is from the most important spiritual ceremony of the Hopi,' you walk away."

Bruce notes that few individuals have been prosecuted under NAGPRA laws. "So far, NAGPRA hasn't hit the private guy," Bruce says. "A few things have been demanded back at auctions, and the owner has done that. But every time you go to the major show in Santa Fe, Indians are looking for something that would fall into the NAGPRA category. It's just a matter of time before a major case is taken against an individual on the market." Bruce says that this is the reason why many dealers and major Native American collectors are increasingly leaning toward buying Native American paintings, pots and rugs, which are just less likely to fall under the NAGPRA legal definition of a cultural item.

Yet if you are unsure whether NAGPRA applies to a certain piece you are interested in buying or selling — the law is often open to interpretation — both Dr. Molloy and Bruce recommend that you make sure to obtain a written receipt that lists a well-documented chain of ownership.

"Make sure to get paperwork by a reputable seller so you have something to stand on if it blows up in your face," Bruce says. "If the guy says it's not a problem to buy it, have him put it in writing. If there is a problem, you can take him to court and say you want your money back."