Dard Hunter's "Old Papermaking"

In ANTIQUES ROADSHOW's Junk in the Trunk 3, Francis Wahlgren appraises a 1923 first edition of 'Old Papermaking,' by Dard Hunter — the first completely handmade book about making books by hand.

The first edition volume (number 104 of 200) of Old Papermaking that Francis Wahlgren appraised at the Cincinnati ROADSHOW in July 2012 for $5,000.

Nov 4, 2013

BY Ben Phelan

A few years ago while collecting piles of newspapers and magazines for his sons' Boy Scout paper drive, Darell came across an old plastic container full of junk paper. He happened to look a bit more closely at the contents and discovered an antique-looking book called Old Papermaking that seemed worth rescuing from the recycling plant. And when he brought the book to the Cincinnati ANTIQUES ROADSHOW in July 2012, Darell found out it was a stroke of luck: Old Papermaking is a rare, prized work, handmade by a craftsman and aesthete named Dard Hunter, in 1923. Hunter is undoubtedly the most important figure in the history of American paper making, and authored several books on the subject. Because of Hunter's historical significance and the excellent quality of the rescued book, Francis Wahlgren, head of Christie's Rare Books and Manuscripts department, estimated the value of Darell's hand-numbered volume (104 of 200) of Old Papermaking at around $5,000.

Dard Hunter, whose given name was William, was born in 1883 to a wealthy newspaperman father. The elder Hunter was a thoroughly modern man who employed modern printing presses at his newspapers, but he was conflicted about the technology that had made him his fortune. As a skilled woodcarver, he bemoaned the encroachment of mass production into everyday life. More and more of the objects Americans interacted with in their daily lives were not made by their fellow citizens, but manufactured by machines. The ubiquity of manufactured goods ruptured civic life, in that they interposed themselves in relationships that had previously been between human beings, but the main objection was aesthetic. In the elder Hunter's view, no object made by a machine could deliver the same pleasure as one made by the hands of another person.

Young William Hunter grew up around his father's newspaper, where he was employed as an illustrator, and absorbed his father's love of the handcrafted. His primary interest, at first, was in design. In 1904, he started working at Roycroft, the influential design collective that operated in East Aurora, New York, around the turn of the 20th century. As he embarked upon his career, he decided to take the peculiar name “Dard.” Cathleen Baker, author of the Hunter biography By His Own Labor, says it's unclear why.

“Dard isn't a name. It may be a contraction of 'darling,' which his older brother supposedly couldn't pronounce, but I find that implausible,” she says. Whatever the source of his adopted name, Hunter's goal was to remake himself, which Americans of the day did without a second thought. “Prior to the 1920s or so, people were not very interested in personal details. Passports weren't required; people didn't have birth certificates. They changed their names at will.”

At Roycroft, Hunter, now called Dard, revamped its entire design aesthetic, orienting it away from Renaissance inspired tropes and toward something new, elegant, and above all modern. He designed stained glass lamps, hammered-copper desk accessories, inkwells, letter openers, and furniture, employing the clean, geometric lines of Art Deco. The Roycroft work is “sensational,” says Baker, but there isn't much of it: Hunter left the Roycrofters in 1910, moving to Vienna. Shortly thereafter he moved again, to London, where he saw a museum exhibit that changed his life.

“Hunter went to the Science Museum in South Kensington and saw these displays on paper making, type founding and printing, and was like, 'Oh, my God,'” says Baker. “He realized that handmade paper was what he was really interested in. By that time there were no mills in the U.S. that were making paper by hand — you had to buy it from England or France. So he built a paper mill by hand and taught himself.”

The paper Hunter most admired was the lusciously textured paper from the Renaissance, so he built his mill using Renaissance-era technologies. To drive the beater that broke down the wood and cloth fibers for his paper, he used a wheel powered by water. He designed his own typeface and cast it, and then, in 1915 and 1916, produced two books on the craft of papermaking. He created them entirely on his own, taking onto himself the work of a dozen men, although for some reason he never bound any of his books himself. The task may have been too straightforward, says Baker, to hold his interest

For an aesthete of Hunter's rarefaction, the first two books were disappointments. His water-wheel system was too crude to produce paper of the quality to which he aspired. The flaws were hardly glaring to the non-specialist though, and in fact were period-correct.

“They were charming books,” says Baker. “If someone was used to handling lots of paper from the Renaissance, they'd know there was a lot of bad paper around then, so Dard Hunter's paper could be seen to be like that. Of course, there was lots of beautiful paper, too, and he knew he'd never be able to come up to that level.”

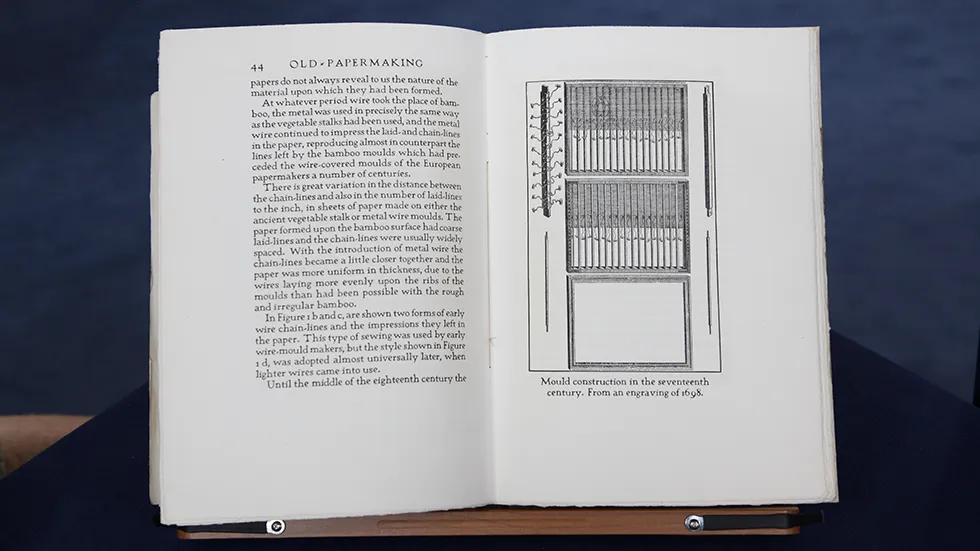

When he set out to write, print and publish Old Papermaking, Hunter outsourced the making of the paper, though in the most quality-controlled manner possible. He contracted with a handcrafted paper maker in England, to whom he sent his paper molds, design specs, and the desired fiber ratios. Once the paper was delivered, Hunter put the rest of the book together in his typically exacting process.

Hunter never stopped publishing books on papermaking; with his encounter at the Science Museum, he had found his life's work. His most famous book, however, was not one of his immaculate self-productions with a tiny press run, but a scholarly work printed by a traditional publisher. Hunter's magnum opus, a 700-page history, titled Papermaking: The History and Technique of an Ancient Craft, came out in 1943, and is still in print.

For those outside the arts-and-crafts movements of the early 20th century, Dard Hunter's obsession with paper must have been odd, a seemingly luddite obsession with an obsolescent technology. Had not modern printing techniques made books easier to produce and cheaper to acquire? In many ways, Hunter would have been more at home in the current historical moment, which has seen a resurgence of interest in handcrafted goods of all kinds: small-run chapbooks, beer from micro-breweries, artisanal pickles, everything on Etsy.com. Even Hunter's approach to writing, as Baker points out, is surprisingly modern.

“Nobody wrote about the trades back then,” she says. “They were beneath notice. Even scholars, the most they'd do was stand around and watch somebody do something. They'd certainly never do it themselves. But Dard Hunter really made paper, and really cast type and printed on a hand press. Embedding yourself in the situation — that's modern journalism.”

Such ironies abound in Hunter's work: In returning to the past, Hunter anticipated the future. Old Papermaking, appraised at $5,000, is a handmade book about making books by hand. The most recent irony, though, is the one Darell enacted when he brought his copy in to the Cincinnati ROADSHOW: He prevented a book about making paper from being made into paper.