Apr 13, 2007

When ANTIQUES ROADSHOW stopped in Salt Lake City in June of 2006, a good number of objects that visitors brought in had some connection to the history of Mormonism, which was no surprise as Salt Lake City history is largely Mormon history. But it was intriguing that three separate visitors arrived with valuable collections from the 1850s, an important pioneer decade in Mormon history.

An overview of how the Mormon Church was founded, and what led it to the "New Zion" of Salt Lake City

One of the items was a collection of personal documents that belonged to Philip Margetts, a Mormon convert and actor who arrived in Salt Lake City in 1850 and who knew Brigham Young (SLC Hour 1); another was a rare first edition of a sacred Mormon book, The Pearl of Great Price, originally a proselytizing document (SLC Hour 2); and another included two documents that refer to the so-called Utah War of 1857, which threatened to pit U.S. government troops against the Mormons (SLC Hour 3).

These three sets of items present the chance to take a closer look at the early history of the Mormon faith and the establishment of Salt Lake City as the promised land of the Mormon Church.

Sacred Texts

What is today known as the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS), or the Mormon Church, was established in the early 1830s by a man from western New York named Joseph Smith, Jr., a charismatic religious leader who many came to view as a prophet. Smith believed that God had chosen him to establish the true Church of Jesus Christ in America. His teaching held that other Christian churches had long ago been corrupted, and that no authentic Christian church any longer existed.

Smith said that for several years during the 1820s he had received visitations from an angel, who eventually led him to find, and then translate, a set of engraved golden plates created by an ancient prophet named Mormon. The resulting translation became the Book of Mormon, which Smith asserted was another Christian gospel and which became the foundation of the Mormon faith. Together with the Book of Mormon, Mormons have three other works that are standard to their faith: the King James version of the Bible, and two additional books of scripture, the Doctrine and Covenants and The Pearl of Great Price.

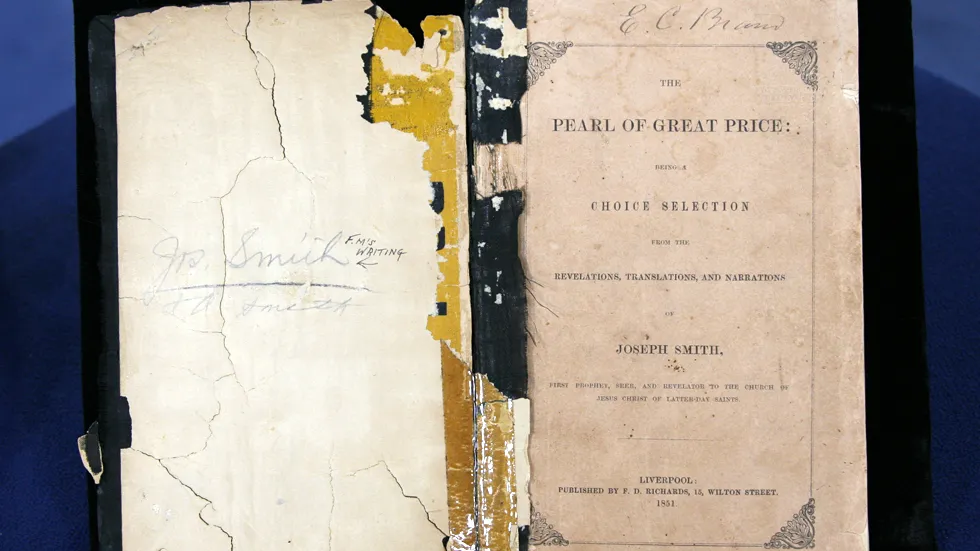

The first edition of The Pearl of Great Price, published in Liverpool in 1851, was valued by rare-books expert Ken Sanders at up to $10,000. The book is a collection of early Mormon pamphlets that includes the Church's Articles of Faith; Smith's interpretation of the Book of Genesis and the Gospel of Matthew from the Bible; Smith's translation of an ancient Egyptian papyrus that he said contained the story of the ancient Jewish prophet Abraham while he was in Egypt; and Smith's autobiographical account of his early life that included an account of his "First Vision."

A view of early Salt Lake City, ca. 1860. Visible in the bottom left corner of the picture is one of the border walls of Temple Square, which today houses many of the Mormon Church's most important landmarks.

Sanders also mentioned on-air that Brigham Young actually did not want The Pearl of Great Price published at the time, in part because he didn't believe that the book was proper scripture. But according to Sanders there might also have been another reason. The publisher of the 1851 edition, Orson Pratt of Liverpool, a Mormon theologian and publisher, received the manuscript from a rival faction of Mormons who were associated with the descendants of Joseph Smith, known as the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, or RLDS.

RLDS, which included members who were related to Joseph Smith, were a rival to Brigham Young and the Utah Mormons. "There was this huge power struggle between the LDS and the RLDS," says Sanders, noting that Young might have feared the book and its Smith lineage would have granted the RLDS a legitimacy that he didn't want them to have. A second edition of The Pearl of Great Price was only published again in 1878, a year after Young died.

Outsider Hostility and Westward Movement

Smith drew many followers, but the Mormons also attracted hostility from many Americans who were threatened by the Mormons' tendency to settle in tight-knit communities — what the Mormons referred to as "the gathering." Many outsiders were also critical because the Mormons were led by someone who claimed to be a living prophet and considered themselves to be God's true chosen people. A further threat was the economic and political power that resulted from the Mormons' industriousness and the cohesiveness of their communities. More than once, the Mormons were violently attacked. In 1839, they fled from Missouri, where they had settled temporarily, creating a new city in Illinois named Nauvoo, where some 15,000 converts eventually gathered. There, in 1844, Joseph Smith was killed by an angry mob.

Before he was murdered, however, Smith had prophesied that his followers would journey to a "New Zion" somewhere in the Rocky Mountains, and in 1846 the Mormons did travel west once again. Unlike other western settlers, the Mormons went west not for gold, work, or adventure, but for a place to worship without persecution. Smith's successor, Brigham Young, himself a strong and able leader, led a wagon party across the Missouri River, then the western border of the United States, into what at the time was Mexican territory.

When Young arrived in the Salt Lake Valley he said, "This is the right place." It was, in effect, a place that no one else wanted. The arid Salt Lake basin became the Mormons' promised land, their "Zion in the Tops of the Mountains," which they called the State of Deseret. Following the Mexican War, a large area of land including Salt Lake City was annexed by the United States, and it became the territory of Utah in 1850.

Society Flourishes in Salt Lake City

Over the next two decades, tens of thousands of people, converted to the faith by Mormon missionaries, migrated to Great Salt Lake City, as it was then called. Many immigrated from as far away as Great Britain and Scandinavia; one such convert was an Englishman named Philip Margetts, who came in 1850.

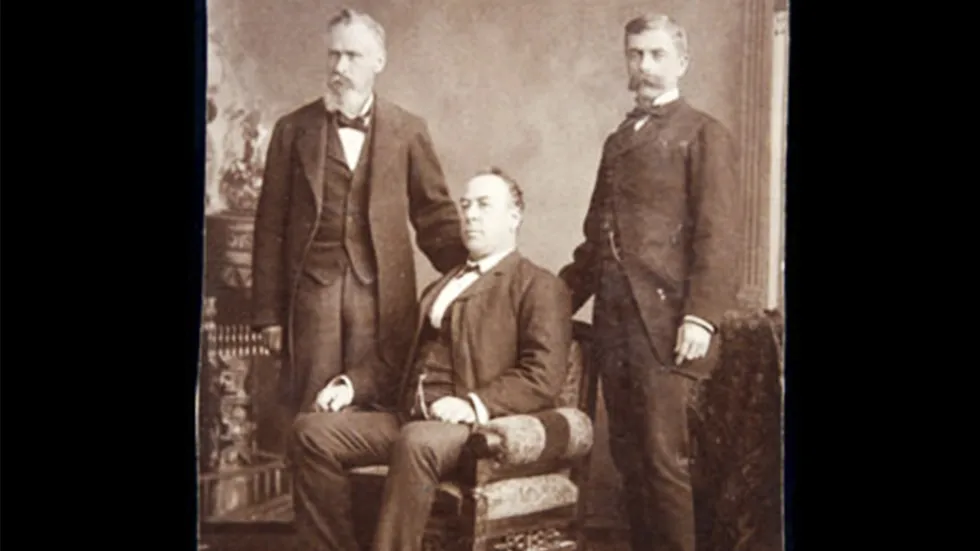

Philip Margetts (center) was an actor who settled in Salt Lake City in 1850.

"He mostly made his living as a blacksmith and also as an owner of a wine depot," said Michelle, Margetts' great-granddaughter, who brought in a collection of her ancestor's memorabilia that books and manuscripts expert Thomas Lecky appraised for between $100,000 and $150,000. She showed one photograph of old Salt Lake City that included a sign on a building for the California Wine Depot, owned by Margetts.

But Margetts' "real passion was acting," Michele said, "and he was Utah's best-known and best-loved actor in the Utah territory from about 1850 to his retirement in 1905." Michele's archive included 19th-century playbills, a ticket to a Salt Lake City show, Margetts' diary, and about a dozen photographs of Margetts playing comic roles in comedies, which were purportedly preferred by Brigham Young. The collection even included three letters written by Young to Margetts about benefit performances intended to raise money for the local theatre troupe to which Margetts belonged.

The "Utah War" of 1857

Other letters in Michelle's collection, dated from June 1857, are between Margetts as he traveled to England to serve as a missionary, and his wife Elizabeth, who remained behind in Utah. In them, the two discuss rumors that, as Elizabeth puts it, U.S. soldiers "are a-coming here this spring to kill us all off" — though both had their doubts. "That is an old story," Elizabeth writes; Phillip calls the rumors "humbug."

But the U.S. Army would indeed "invade" Utah soon thereafter, in large part because of intense hostility that had grown back east after Mormons made a public acknowledgement in 1852 of the practice of plural marriage. This led the Republican Party in their 1856 campaign platform to denounce polygamy as one of the "twin relics of barbarism," slavery being the other.

Brigham Young responded by urging Mormons to "repel any and all such invasion" in his defiant "Invasion Proclamation," which was brought in by another Salt Lake City Roadshow guest. The visitor also presented appraiser Ken Sanders with a textile-printed advertisement for an emporium owned by his great-grandfather in Great Salt Lake City. In an interesting contemporary allusion to the tensions, the text of the ad encouraged residents to stock up for the assault.

"What I found fascinating about this piece," Sanders said, "is down here, underneath the graphic," referring to a caption on the ad that reads, "The Mormon War goes on and supplies have arrived at the Universal Emporium." The ad depicts a line of people outside the store waiting to stock up from the seller's inventory of bonnets, cutlery, shoes, boots, hats, and carpets. (The two items together were estimated to be worth between $10,000 and $15,000.)

In 1857 U.S. President James Buchanan sent an expedition force to Salt Lake City with orders to wrest control of Utah from Young and the Mormons, triggering the "Utah War." The term is an exaggeration, however, as the Mormons temporarily abandoned Great Salt Lake City before the federal troops arrived, and the two sides never exchanged gunfire.

Federal Reconciliation

Instead, the two sides reached a negotiated settlement and Young remained the de facto governor of Utah until his death in 1877. But pressure on the Mormons for change continued to mount as, beginning in 1862, the U.S. Congress passed a series of laws against the practice of polygamy. In 1887, Congress passed the Edmunds-Tucker Act, which took the vote away from all women and polygamous men; declared all children of plural marriages illegitimate in the eyes of the law; and froze the Mormon church's assets, bankrupting the church.

In 1890, in an effort to protect the Church in the face of these government policies, Mormon president Wilford Woodruff issued his "Manifesto." In it Woodruff renounced polygamy as a Mormon practice and separated the Church's political, religious and economic structures. Perhaps more than any other single event, these changes marked a turning point for the Mormon Church that has enabled it to thrive in relative peace, free of government interference. Utah was admitted to the United States as the 45th state on January 4, 1896.

A first edition of The Pearl of Great Price brought in to the Salt Lake City Roadshow in June 2006. It is a sacred book in the Mormon faith.