Explainer: What Is Photogravure?

Picture this: photography without the darkroom. Step into the light to explore this fascinating photomechanical process.

Feb 14, 2005

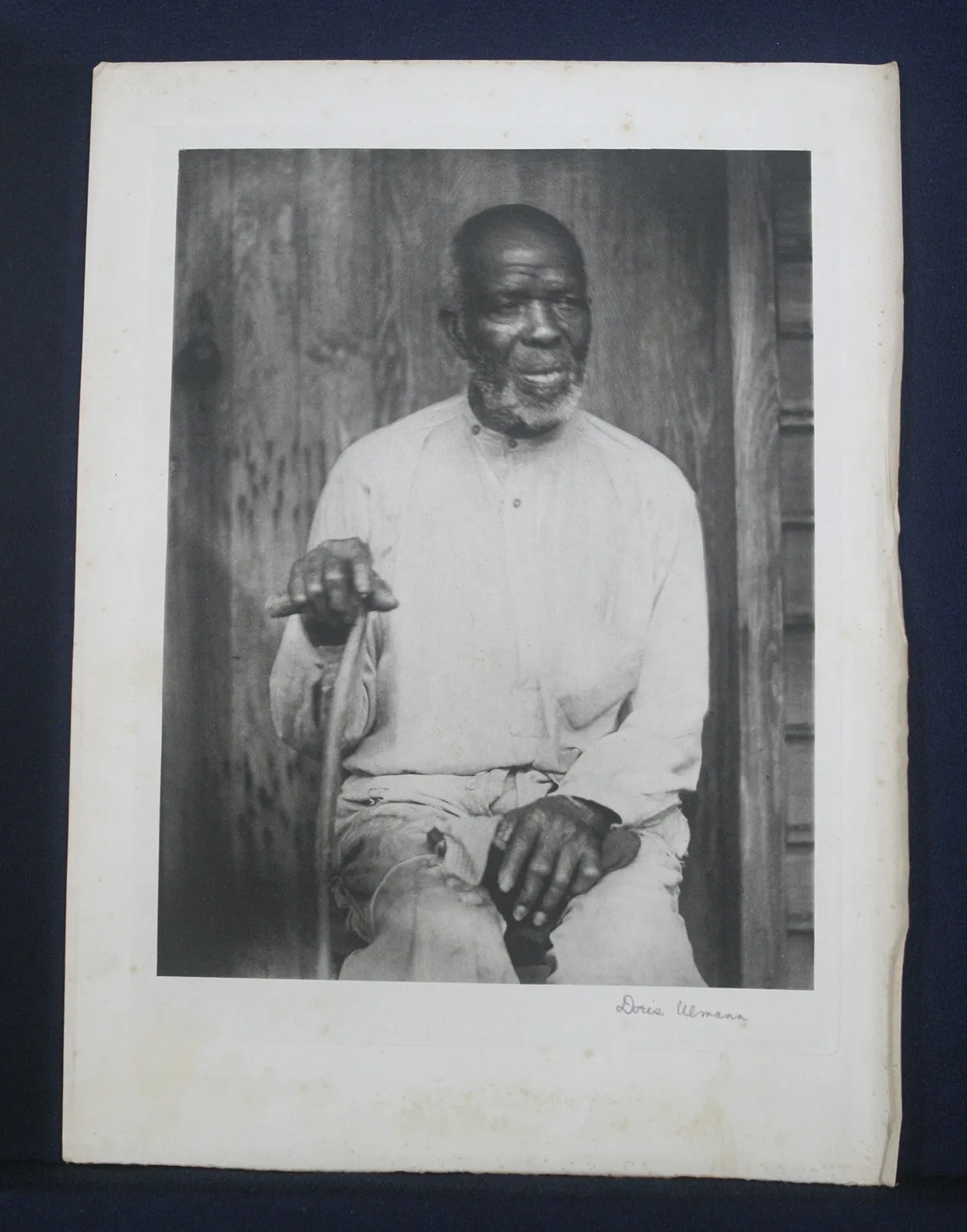

At the Memphis ANTIQUES ROADSHOW, a guest arrived with one of the classic photographic books of the 20th century, Roll, Jordan, Roll, which contains images by the New Yorker Doris Ullman, a photographer who was known for her intimate portraits of marginalized Americans. In Roll, Jordan, Roll, published in 1933, she took portraits of the Gullah people, descendants of slaves who developed the unique African-American culture in the islands along the South Carolina coast. The book included an image of the guest's gray-bearded father-in-law, a lawyer who is shown wearing a white cotton shirt, his right hand perched on a cane.

The image has the realistic detail we associate with a photograph and a subtle range of whites, grays, and blacks typical of a fine art print. Daile Kaplan, an ANTIQUES ROADSHOW appraiser who works at Swann Galleries in New York City, told the guest that the image of her father-in-law, like all the others in the Ullman book, is a photogravure. The appraiser didn't have time on-air to describe what a photogravure is, so we asked her to tell us more about this classic printing technique.

"A photogravure is the most sophisticated of the photomechanical processes," Daile explained. "So strictly speaking, it's not a photograph. The image isn't made in a darkroom. Rather, the photographer's negative is transferred onto a copper plate, which is used to print or engrave the image with ink."

Daile said that the photogravure process, which is an involved and an expensive one, is one of the best methods ever developed to mass produce large editions of photographs for high quality books and magazines. For an exhibit or for sale, Ullman would create luscious platinum prints in her darkroom. But when she wanted to create hundreds of images for her beautifully produced book she, like many fine art photographers of the early 1900s, chose the photogravure.

"I'm sure she felt the photogravure could match the delicate tones and richness of platinum prints," Daile said.

The photographer and art dealer Alfred Stieglitz rendered the photographs of Paul Strand, Edward Steichen, and others into photogravures for his seminal art magazine of the early 1900s, Camera Work, the first to champion photography as a medium of creative expression. Edward Curtis, the photographer who chronicled Native Americans in photographs he took from the 1890s through the 1920s, also used photogravures in his series The North American Indian, a 20-volume compilation of his photogravures. Today, the magazine 21st: The Journal of Contemporary Photography is one of the few publications that uses the refined photogravure process.

"Photogravures have a very sensual, almost velvety quality," said Daile. She notes that photographers would sometimes choose tinted inks for their photogravures. Ullman stuck with black inks but Curtis used a brownish ink to create his sepia-toned portraits and landscapes. Photogravures were far superior to alternative photomechanical processes of the time, such as the half-tone reproduction used in newspapers. These consisted of photo-engravings made from an image photographed through a screen. The result was a reproduction of poor quality consisting of a series of very small dots.

For more information on Ullman's Roll, Jordan, Roll and other classic photographic books, see:

Book of 101 Books: Seminal Photographic Books of the Twentieth Century, Editor: Andrew Roth. Roth Horowitz, 2001.

Image from Daile Kaplan's appraisal of early 20th-century "Camera Work" magazines.