Explainer: Who Was Charles Rennie Mackintosh?

Christian Siriano has a pair of sculptural reproduction Mackintosh chairs — but who was "Mackintosh"? Roadshow expert David Rago tells us more about this enigmatic genius of early modern design.

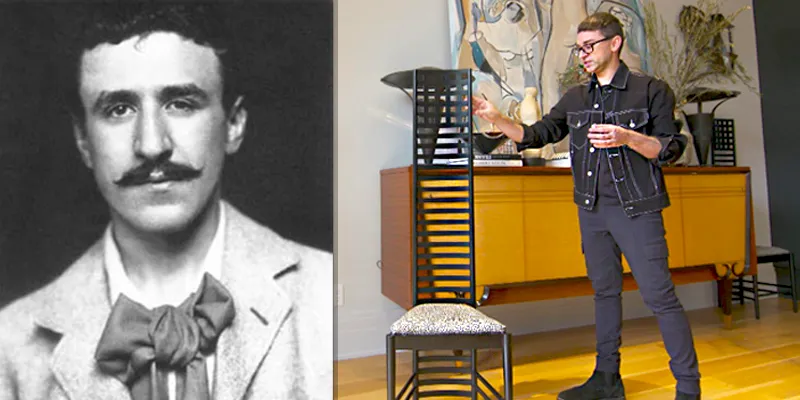

Charles Rennie Mackintosh (left, ca. 1900), an enigmatic genius of early modern design. Christian Siriano (right) shows off one of his reproduction Mackintosh-style chairs during ANTIQUES ROADSHOW's visit to see Siriano's collection of decorative arts in August 2020.

May 17, 2021

BY David Rago

I FIRST LEARNED of Charles Rennie Mackintosh, the visionary Scottish architect, designer and artist, in the 1980s — though in the beginning I didn’t know enough even to know what I didn’t know. To me, he just seemed like a cool “euro” guy — I’d heard of the famous Willow Tearooms he’d designed in Glasgow. There were probably a few pieces that came up in the New York City sales here and there, but I barely had any understanding of him, his equally creative wife, Margaret Macdonald, or their work together.

To be sure, Mackintosh has been highly revered but, like most of the small cadre of high-end designers, his work was mostly site-specific and not really for general production — which means we seldom see pieces of his on the market.

Today, in my opinion, Mackintosh is perhaps revered more in America than Europe because of how his work at once laid the groundwork for 20th-century design innovations, like the Arts and Crafts Movement, but showed the potential for startling beauty in a genre that is often dull and subdued. I once saw what I called Mackintosh’s “yellowjacket” room, at 78 Derngate in Northampton, England — a surprising motif of all yellow and black — and was simply blown away by it. It was all straight lines and angles, but so alive, visually stimulating, and driven by such a perfect overall concept of an interior, where wall treatments and furniture, lighting and color, all worked in a perfect harmony.

Think of Christian Siriano’s Mackintosh-style chairs, and imagine actually sitting in one of them for more than 10 minutes. It is sculptural to the point of being non-functional as a chair (all it would need to become more so is a spike in the center of the seat!). So what? — You can hang your hat or your coat on it, or use it as a pedestal for a sculpture. You make it work somehow because it’s so beautiful and other-worldly that it’s worth the inconvenience.

As I said, attractive though they are, Christian’s pair of chairs are fairly recent (ca. 1970) Mackintosh-inspired reproductions by Cassina. In fact, it is common to see a great deal of reproduction Mackintosh furniture; his style has become iconic, yet it was never scaled for common release. I believe I handled one authentic coat rack in an auction of ours about 10 years ago. We attributed it to CRM and people seemed to agree it was by his hand. We placed a relatively low initial estimate on it, and I believe it brought around $25,000. But this is rare stuff indeed, and originals are hard to come by.

Mackintosh the Man

For those who may have a more academic interest in Charles Rennie Mackintosh, he was born in Glasgow in 1868. He apprenticed as a young man with local architect John Hutchison before transferring to the larger city practice of Honeyman & Keppie. At the same time, Mackintosh also enrolled in evening classes at the Glasgow School of Art, pursuing various drawing programs and honing his skills by studying all the latest architectural and design journals in the school’s library.

Mackintosh proved to be quite the rising star at Honeyman & Keppie, designing the Glasgow Herald Building in 1894 and the Martyr’s Public School in 1895. In 1896, he won the commission that would become his masterwork: designing a new building for the Glasgow School of Art.

Mackintosh was a fierce believer in artistic freedom and independence, and his work exhibited an eclectic mix of styles and influences. Glasgow was a prosperous production center of heavy engineering and shipbuilding, and like so many cosmopolitan European cities at the time, it teemed with a fertile combination of industrialization, emerging modernist ideas, as well as Asian style. Mackintosh was particularly fond of the developing Japoniste style and its simple forms, natural elements, and tendency toward restraint over ostentation. He combined this simplicity with the innovative ideas and new technologies of modernism, and sometimes even the subtle curves of Art Nouveau, into a unique visual language all his own.

The originality of Mackintosh’s style was well-received in much of Europe, especially in Austria and Germany. Despite his success abroad, his work was not nearly as popular in his home country and he relied primarily on a small handful of patrons and supporters for most of his commissions. His career soon declined and around 1914 he and his wife moved to London, where his efforts to continue his work were curtailed by the first World War. Mackintosh then moved to the South of France in 1923, where he spent the remaining years of his life painting. He died in London in 1928.